On 8 August 1942, as the Second World War reached India’s doorstep, Mohandas K. Gandhi delivered a speech in Bombay demanding that the British ‘quit India’ once and for all. Shortly thereafter, the British government arrested Gandhi and many Indian National Congress leaders. With prominent Congress politicians behind bars, local activists led what become known as the Quit India movement, as protestors throughout India took to the streets, burned government offices and property, and targeted British administrators.

A group of college-age and Bombay-based friends came up with an ambitious plan: setting up an underground anticolonial radio station. The station, they surmised, would air news of the current uprisings as they were developing throughout India, bypassing British censorship of print media, and inspiring more to join the call for the British to quit India once and for all.

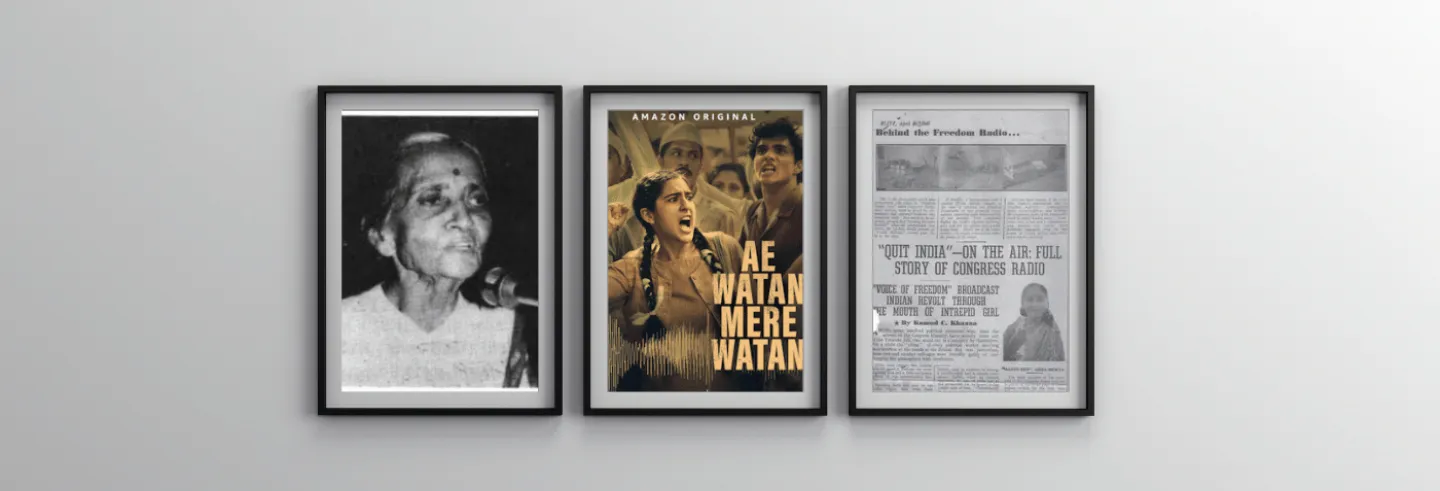

This underground station, which came to be known as Congress Radio, and its leading broadcaster Usha Mehta, have been the subject of a new book and a recent Bollywood movie.

In its own time, Congress Radio’s influence had less to do with the actual broadcast content than with the air of insubordination the station’s presence on the airwaves conveyed, regardless of how limited its transmitter’s reach actually was and how few people could tune in. Congress Radio was neither the first nor the only attempt to start an underground radio station. During the Quit India movement there were at least three other makeshift underground radio stations located in Calcutta, Ahmedabad, and Pune. None of these other local radio stations, however, became as well-known as Congress Radio. In part, the station’s fame was because of the publicity it gained after a dramatic police raid on the station, the arrest of its organisers and the subsequent court case.

In a typically patriarchal slight, the judge who later tried Congress Radio organisers described Mehta, the only woman in the group, as ‘a lieutenant’ of her male comrades.

That, however, didn’t meant that Congress Radio’s message didn’t reach people. In my previous work on radio broadcasting, I employed the concept of “radio resonance” to account for how conversation, “rumour, and gossip can intensify, expand, enrich what is being broadcast on the radio and to account for the affective bonds this talk could create.” While Congress Radio was certainly not alone in relying on word-of-mouth, the station stands out in that the resonance it created was less about the material being broadcast (even though this remained significant) than about the extraordinary story of how a group of young, largely unknown young anticolonial activists had successfully managed to deploy radio technology against imperial rulers. Distinct from other underground stations, Congress Radio stood out in that its message continued to spread after the Bombay police had effectively shut it down.

The war in the ether

The four leading organisers of Congress Radio were Usha Mehta, Vithaldas Madhavji Khakar, Vithaldas Kanthadabhai Jhaveri and Chadrakant Babubhai Jhaveri. None were well-known activists or held leading positions in the Indian National Congress. They were also not were trained broadcasters or had any significant experience with radio broadcasting.

Their interest in radio appears to have been born out of thin air, but in the literal rather than the figurative sense. The four were likely inspired by the growing presence of Indian-language Axis radio broadcasts from Germany and Japan that filled the airwaves as the Second World War broke out. Subhas Chandra Bose, who had sided with the Axis powers, made his first radio broadcast in the days following the fall of Singapore and continued to broadcast during the Quit India movement. Largely in response to the growing popularity of Axis radio broadcasts, the British government in India – until then hesitant to build broadcast infrastructure – made its first genuine, albeit belated and haphazard attempt to reach the general population through the medium of radio and developed the national network, All India Radio.

Congress Radio’s organisers began their project in the summer of 1942 with a rather ambitious goal. Their initial plan was to set up a network of underground stations throughout India, ensuring that if the government were to shut down one transmitter, as it effectively did, another transmitter would already be ready to replace it.

Congress Radio was making clear the station’s commitment to the idea of Hindustan as a religiously inclusive homeland and rejecting any version of Indian nationalism that sought to exclude Muslims.

Usha Mehta, a 22-year-old student, took a leading role in the project. In a typically patriarchal slight, the judge who later tried Congress Radio organisers described Mehta, the only woman in the group, as "a lieutenant" of her male comrades. Evidence, however, shows that Mehta’s part in the project was vital. Mehta was one of very few Indian women on the airwaves during the war, and her voice helped the station garner attention. Prior to her work with Congress Radio, Mehta had been a passionate Gandhi supporter and had taken to wearing khadi, but had avoided large public demonstrations. During the Quit India movement, however, the young Mehta shed her reticence as she quite literally found her voice.

For technical matters, the group relied on Nariman Printer, a trained radio technician. According to the court findings, unlike all other Congress Radio organisers, Printer joined the group purely for financial motivations. Other individuals involved included the writer and film director Khawja Ahmad Abbas, and Nanak G. Motwane, the director of Bombay’s largest wireless dealer. Motwane helped supply parts for the transmitter and arranged for the filming of the All India Congress Committee’s (AICC) famous August Quit India declaration, which was later transposed into records and aired on Congress Radio. Finally, Ram Manohar Lohia, an established socialist Congressman, supported the station and played an important, if behind-the-scenes, role.

‘This is Congress Radio calling’

Congress Radio broadcasts always began with: “This is Congress Radio calling on 42.34 meters from somewhere in India,” followed by a musical rendition of Sare Jahan Se Achcha Hindustan Humara. Programming closed with a musical rendition of Vande Mataram.

The choice of these two songs was highly symbolic. The first poem was an anthem to the idea of Hindustan as a shared homeland for people of all faiths penned by the renowned Urdu and Persian language poet, Muhammed Iqbal. In choosing this poem, Congress Radio was making clear the station’s commitment to the idea of Hindustan as a religiously inclusive homeland and rejecting any version of Indian nationalism that sought to exclude Muslims. The second was a poem by the Bengali writer Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay and adopted by the Congress Working Committee as a national song in 1937.

These two compositions which opened and closed all of Congress Radio’s broadcasts became essential aspects of the station’s identity and aesthetics, signature tunes by which listeners could recognise the station. On various occasions, Congress Radio broadcasters reminded listeners that even if the reception was unreliable and they could not make out the broadcasts, they could always tell Congress Radio apart from other stations by its opening and closing tunes.

Congress Radio also aired its own original talks focusing on workers’ rights and clearly aligned the station with the party’s left-leaning wing.

Congress Radio’s primary broadcast language was Hindustani, but in later months, the station also added English translations of broadcasts. The station’s programming consisted of three main items: recordings of AICC speeches, political talks, and Quit India news updates. The AICC speeches that Congress Radio broadcast appear to have included both original recordings featuring Congressmen’s actual voices as well as transcripts of speeches read by Congress Radio broadcasters. If the British government had succeeded in silencing the leadership of Congress by arresting its main leaders, Congress Radio quite literally gave voice back to the anticolonial organisation by successfully bringing these leaders’ voices to the airwaves.

Congress Radio also aired its own original talks focusing on workers’ rights and clearly aligned the station with the party’s left-leaning wing, to which Lohia belonged. Finally, news updates about Quit India constituted the third major item on Congress Radio. These broadcasts consisted of new bulletins that listed information about uprisings in various cities.

We know little about Congress Radio’s news sources. Mehta noted that Lohia received news directly from Quit India organisers, who then passed it on to Congress Radio broadcasters, but she does not provide details about the original sources. A British investigator, in contrast, concluded that Congress Radio broadcasters likely reproduced news about Quit India first aired on Axis radio stations. Neither party provides enough evidence to reach a firm conclusion about Congress Radio's news sources. A close reading of transcripts, however, does reveal that Congress radio undeniably echoed some of Axis radio’s leading themes, even if Congress Radio never voiced support for Axis countries. It is, for example, rather telling that Usha Mehta referred to All India Radio (AIR) as “Anti-India Radio” a term Subhas Chandra Bose used repeatedly in radio broadcasts.

To not raise suspicion in the streets, the group hid the equipment in suitcases and pretended to be a family moving apartments and going about their ordinary lives.

It is therefore not surprising that listeners sometimes confused Congress Radio for an Axis station. Abbas, the film director, remembered that during a Communist Party of India meeting, his comrades discussed the new station on the air and concluded that this Congress Radio had to be another counterfeit station operating from Germany. Abbas explained: "I was not in a position to contradict them or to say that I had just come from this secret radio station and that it was a stone’s throw away from the Communist Party."

Congress Radio relied on a low-power transmitter whose reception could be heard only within a small radius in the city of Bombay. Even within that circle, reception remained a constant problem. The Bombay police’s own transcripts of broadcasts are peppered with complaints about reception and give us a sense of the difficulties listeners likely experienced when tuning in to the stations: “Voice indistinct”; “station closed abruptly at 9:40 pm”; Reception being poor”. Broadcasters asked listeners to have patience and to not “switch of the radio,” even if they could not hear Congress Radio clearly. “We are always on the air from 8:45 pm till you hear Vande Mataram.” “Move between 39 and 43 meters, which at times is necessary.”

Congress Radio explicitly encouraged listeners to carry the message forward by talking about what they had heard on the radio. As Mehta herself noted: "Our listeners help us further in broadcasting out news to the people at large." 1Misc Item Accession no 99: The Congress Radio calling.’ Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi On the airwaves, broadcasters urged listeners to “to talk” about broadcasts. One broadcaster noted: “talk of our appeals to different classes of the population” (cited in Thakkar, 137). The voices of listeners carrying the message forward, the broadcaster explained, were not auxiliary to the station, they were the voice of Congress Radio. “Let the whole country resound with a million voices all trained to talk uniformly by the only voice of truth and freedom in the country, the Congress Radio calling.”

Cat and mouse

Setting up a single radio station with a single low-power transmitter was a complicated and risky undertaking. Immediately after the AICC bulletin announced Congress Radio’s inauguration, the police began to regularly monitor its broadcasts. To avoid being caught, the station changed premises several times during the months it was on the air. Each time, broadcasters had to procure a new safe location, move all their broadcasting equipment, and set up the transmitter. To not raise suspicion in the streets, the group hid the equipment in suitcases and pretended to be a family moving apartments and going about their ordinary lives. Once installed in a new place, broadcasters had to be extra careful. In her personal account, Mehta notes she stopped wearing khadi saris while working for Congress Radio to avoid bringing unwanted attention to herself and her colleagues. 1Misc Item Accession no 99: The Congress Radio calling.’ Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi

An ‘Officer Kokje’, who led on-the-ground proceedings, tracked down and questioned Printer – the technical adviser – who agreed to collaborate with the police, likely in exchange for immunity. On 12 November 1942, Printer accompanied Kokje and a few other officers to the flat in Parekh Wadi, where the station was then located. The police barraged through the door and arrested C. B. Jhaveri and Mehta, who were then operating the transmitter, and confiscated all their equipment.

Usha Mehta's desire to put rumours to rest demonstrates that the raid and broadcasters’ imprisonment were particularly effective at creating radio resonance and amplifying the station’s message.

Mehta remembered the raid somewhat romantically. “The arrest formalities took nearly three and half hours. When […] we finally step out we found that there were policemen waiting for us at each and every step all the way down” (cited in Thakkar, 61) .She remembered telling her comrade: “Today we are getting a Guard of Honour – and that too from the rifled policemen.” The following day, the police arrested Khakar, V.K. Jhaveri, and Motwane, the owner of the radio shop where Printer had purchased equipment, at their private homes and work offices.

The radio station’s dramatic raid was covered in newspapers. Moreover, information about the broadcasters’ identities, the work of the radio station, and the raid itself, seems to have spread quickly. Usha Mehta noted in an oral interview that one of the reasons why she felt she had to write her version of events was because she wanted to correct the many false accounts that glorified her own role and incorrectly claimed that the police had tortured her. 1Misc Item Accession no 99: The Congress Radio calling.’ Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi Her desire to put rumours to rest demonstrates that the raid and broadcasters’ imprisonment were particularly effective at creating radio resonance and amplifying the station’s message. The talk that surrounded Mehta’s arrest was also likely related to the uniqueness and significance of her identifiably female voice on the airwaves.

Congress Radio on trial

The government tried the four main organisers and Motwane, the owner of the radio shop, for violating the Indian Penal Code and the Defence of India Rules. The trial started on 8 April 1943, several months after the government had crushed the Quit India movement. The case was heard in a Special Criminal Court, which appears to have been set up exclusively to hear Quit India-related cases. The trial echoed earlier anticolonial trials, and in particular that of Bhagat Singh. As scholars like Kama McLean (51–81) have shown, Singh’s trial and discussions about it played an important role in making him into a national hero.

The three male defendants denied having had any connection with Congress Radio. Mehta, in contrast, pleaded not guilty, but refused to deny her role in the radio station. Later, Mehta came to believe that her decision helped her earn the judge’s respect and resulted in a lighter sentence. In her personal account, Mehta noted that the group considered not putting up a defence at all, but decided to defend themselves because they realised that since the station had been accused of collaborating with Axis countries, “the prestige of the Congress was at stake.” 1Misc Item Accession no 99: The Congress Radio calling.’ Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi

According to Mehta, Lohia and other Congressmen helped cover the cost of the defendants’ lawyers. I have found no collaborating evidence of this, but if Mehta was correct that Congressmen paid the legal costs of these young activists’ defence, then this could serve as further evidence of how the trial helped garner support for the station and its broadcasters – and ultimately amplified Congress Radio’s message.

While Usha Mehta’s account might be romanticised, there can be no doubt that the court case served as an opportunity for the accused to proudly celebrate their commitment to the anticolonial movement.

In an account clearly coloured by nostalgia, Mehta described the trial as an enjoyable event. "All along, we used to chew chocolates or peppermints unperturbed by the efforts of the prosecutor." Mehta wrote that her comrade’s "clever jokes," "artistic sketches," and "literary flashes" during the trial entertained all present. Motwane’s penchant for inserting "Urdu shers into this speech" amused the courtroom.

While Mehta’s account might be romanticised, there can be no doubt that the court case served as an opportunity for the accused to proudly celebrate their commitment to the anticolonial movement. Mehta remarked that one of the most exciting moments in the trial was when the prosecutor noted that the court should listen to the AICC Quit India resolution, which had aired on Congress Radio. The court was unable to find the tape Congress Radio broadcasters had used and instead played the original audio-visual recording in the court. Mehta recalled that “seeing Jawaharlal Nehru on the screen” was particularly thrilling for the four defendants and their supporters in the courtroom. In this way, the trial offered an opportunity to celebrate the materiality of technology and the ways in which it could serve as means of defiance against colonial rule.

Similarly, courtroom arguments about Printer’s motivations and character helped emphasise the defendants’ legitimacy and commitment to the anticolonial cause. The judge pointed out that Printer had knowingly deceived his colleagues about having increased the strength of the station’s transmitter. Printer, the judge noted, was a “unscrupulous” individual, whose testimony could not be fully trusted. Ultimately, the conversations about Printer’s lack of commitment to the anticolonial movement and his questionable character helped bring attention to the defendants’ own heartfelt commitment to the cause.

The most telling deliberation in the courtroom, however, was a back-and-forth between the defendants and the judge about whether Vande Mataram was playing when the police entered the apartment. In her personal account, Mehta explained, "we not only refused to carry out their orders, but [refused] to get up from our seats until the ‘Vande Mataram’ record was over.” 1Misc Item Accession no 99: The Congress Radio calling.’ Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi The judge disagreed with this account, relying on the police report that noted Printer had cut the fuse of the transmitter before the police entered the room, so the song could not have been playing at the time of the defendants’ arrest. The three broadcasters explained that even if the transmitter was no longer working, the gramophone player continued to play the patriotic song and it would have been audible to everybody in the room. To this, the judge responded that if the gramophone player had been playing during the time of the arrest, the needle would have been found resting on the record. The photographs, however, clearly showed that the needle was not on the record.

A careful reading of the events reveals that the dramatic police raid and the prolonged court case ultimately amplified Congress Radio’s message.

The level of detail of these discussions makes it clear that broadcasters felt that it was not only their work with Congress Radio, but their commitment to Indian nationalism which was on trial. Proving that the song was on the air at the time of arrest – that it had served as a soundtrack to their arrest – was ultimately an effort to assert their own and the station’s patriotism.

In the end, the judge found Mehta, Khakar, and C. B. Jhaveri guilty of “conspiracy to establish, maintain and work an unauthorized wireless transmitter.” He sentenced Khakar to five years and Mehta to four years in prison. Mehta came to believe that her acknowledgement of her role in the station helped her gain a lighter sentence than Khakar. The judge sentenced C. B. Jhaveri to only one year because the police could not provide sufficient evidence that he played a role in the initial planning of the radio station. The judge absolved Motwane because the police could not prove that he had been aware that his employees had sold transmitter parts to Printer.

The judge also acquitted V. K. Jhaveri and the justification for this absolution deserves greater attention. The young man’s handwriting appeared in many of the gramophone records the police confiscated. His lawyer, however, argued that gramophone records were not documents because official definitions of a “document” did not include aural material. Agreeing with the lawyer, the judge ruled that the confiscated records could not be used as evidence that Jhaveri was involved in the station. It is indeed ironic that the very thing that made it possible for the station to break through colonial government’s information gag and censorship policies, its aurality and separation from print media, had also, thanks to a lawyer’s savvy reading of colonial legal documents, ultimately saved Jhaveri from doing prison time.

The afterlife of broadcasts

The Congress Radio shut down only months after it went on air. By some accounts, it could be considered an unsuccessful enterprise. However, a careful reading of the events reveals that the dramatic police raid and the prolonged court case ultimately amplified Congress Radio’s message. In fact, the station appears to have been most successful at creating radio resonance after its closure, through discussions about the raid and the trial. As Thomas Mullaney reminds us, technologies need not derive their relevance from the magnitude of their ‘immediate effect’, but from ‘the intensity and endurance’ of the engagement they create.

This essay is adapted from a longer article titled “Broadcasting the ‘(anti)colonial sublime’: Radio SEAC, Congress Radio, and the Second World War in South Asia,” part of the September 2023 special issue of Modern Asian Studies “Rethinking the Second World War in South Asia,” edited by Isabel Huacuja Alonso and Andrew Amstutz.

Isabel Huacuja Alonso is an assistant professor in the Department of Middle East South Asian and African Studies at Columbia University, New York. She is the author of Radio for the Millions: Hindi-Urdu Broadcasting Across Borders.