Caste continues to exert a strong influence on social and economic inequality and inter-generational occupational mobility in India. Yet, the debate over the need for a nationwide caste census continues, and issues related to restructuring the criteria for caste-based reservation remain unresolved. The existing affirmative action policies have also not addressed the hierarchy within castes—how things are at the sub-caste level.

This article attempts to trace occupational mobility across three generations using data from the sub-caste level based on a survey conducted in Uttar Pradesh.

Caste is a system of graded inequality that divides Indian society into separate vertically organised groups (Ambedkar 1917). Caste strongly determines the occupation that individuals join or belong to, thus becoming an important factor affecting the labour market outcome of households.

Most of the social and occupational mobility studies in the Indian context have only analysed gender and social group-based occupational segregation at the national level (Dutta and Satyabhama 2010; Chattopadhyay et al. 2013; Reddy 2015; Agrawal 2016). Occupational segregation and occupational mobility have been studied across constitutionally categorised social groups such as the general category (upper castes), Other Backward Classes (OBCs), Scheduled Castes (SCs) or Dalits, and Scheduled Tribes (STs) (Reddy 2015; Agrawal 2016). Yet, there are very few studies that describe the caste differences within these large social groups. So, with an exhaustive list of sub-castes, we examine occupational mobility over three generations at the sub-caste level.

Importance of sub-castes

Research on caste inequalities in India has focused only on four social groups: general, OBCs, SCs, and STs. However, these are very broad categories and huge inequalities persist across sub-castes, or what is called biradari in Hindi (Tiwari et al. 2022). Because of a lack of information, few researchers in India have attempted to explore economic disparities in general or occupational segregation in particular at the sub-caste level (Deshpande and Ramachandran 2017).

While caste in India is an immobile social affiliation rooted in the Hindu religion (Ambedkar 1917), caste-based hierarchies have expanded beyond Hinduism and have been assimilated into other religions, particularly Islam. Lower caste Muslims are kept out of social protection scheme benefits even now. The Sachar Committee Report on the Social, Economic, and Educational Status of the Muslim Community of India in 2006 identified inequalities within the major caste groups. It reported on the low representation of Muslim OBCs in education and employment and called for affirmative action within the Muslim caste hierarchy.

With huge economic disparities reported within broad caste groups (Trivedi et al. 2016b; Tiwari et al. 2022), occupational mobility and the uprooting of caste-based occupational segregation are important to promote economic mobility and bridge the economic gap between castes (Reddy 2015). Therefore, formulating policies to address the problem of occupational segregation and resultant economic inequalities may require an analysis of workforce division at the sub-caste level.

Data and methodology

The Mandal Commission and Sachar Committee measured socio-economic disparities in broad socio-religious groups using secondary information from large-scale sample surveys conducted in India. The assessment by the Post-Sachar Evaluation Committee, headed by Amitabh Kundu, also used the existing secondary information to evaluate the implementation by the union government (Kumar et al. 2020). However, the lack of unit-level information on sub-castes among OBCs in the censuses and large-scale sample surveys such as the National Sample Survey (NSS), National Family Health Survey (NFHS), and India Human Development Survey (IHDS) makes it impossible for social scientists from being able to identify Dalit and OBC Muslims.

The sub-caste level information on OBC Muslims is critical for identifying Dalit Muslims. The union and Uttar Pradesh governments now identify only OBC Muslims, including Dalit Muslims in the OBC list. Large-scale sample surveys in India do not collect information at the biradari level (by caste names) employing a robust identification strategy (Kumar et al. 2020; Trivedi et al. 2016a).

Our study uses primary data collected by the Lucknow-based Giri Institute of Development Studies (GIDS) under a project titled 'Social and Educational Status of OBC and Dalit Muslims,' conducted in 2014-15 to assess the socio-economic disparities in six socio-religious groups. The groups are Hindu general, Muslims general, Hindu OBC, Muslims OBC, Hindu Dalits, and Muslims Dalits. The data was collected and compiled from responses to three questions that were asked to the respondents—what was their biradari (individual caste name), social group, and religious affiliation?

With this information, we grouped biradari names into sub-castes and later validated this classification with additional information on social and religious groups. For some analyses, we also re-grouped them into the six major groups listed above. Further, the survey asked the head of the households, irrespective of gender, about their main occupation and that of their father and grandfather, generating information on “grandfather-father-respondent” occupational mobility. It was conducted with a state-representative sample of 7,195 households in 14 districts of Uttar Pradesh, employing a standard multi-stage cluster sampling method. This approach involved dividing the population into clusters, selecting random clusters, and then randomly sampling households within those clusters (Kumar et al. 2020; Trivedi et al. 2016a, 2016b).

Caste and intergenerational occupational mobility

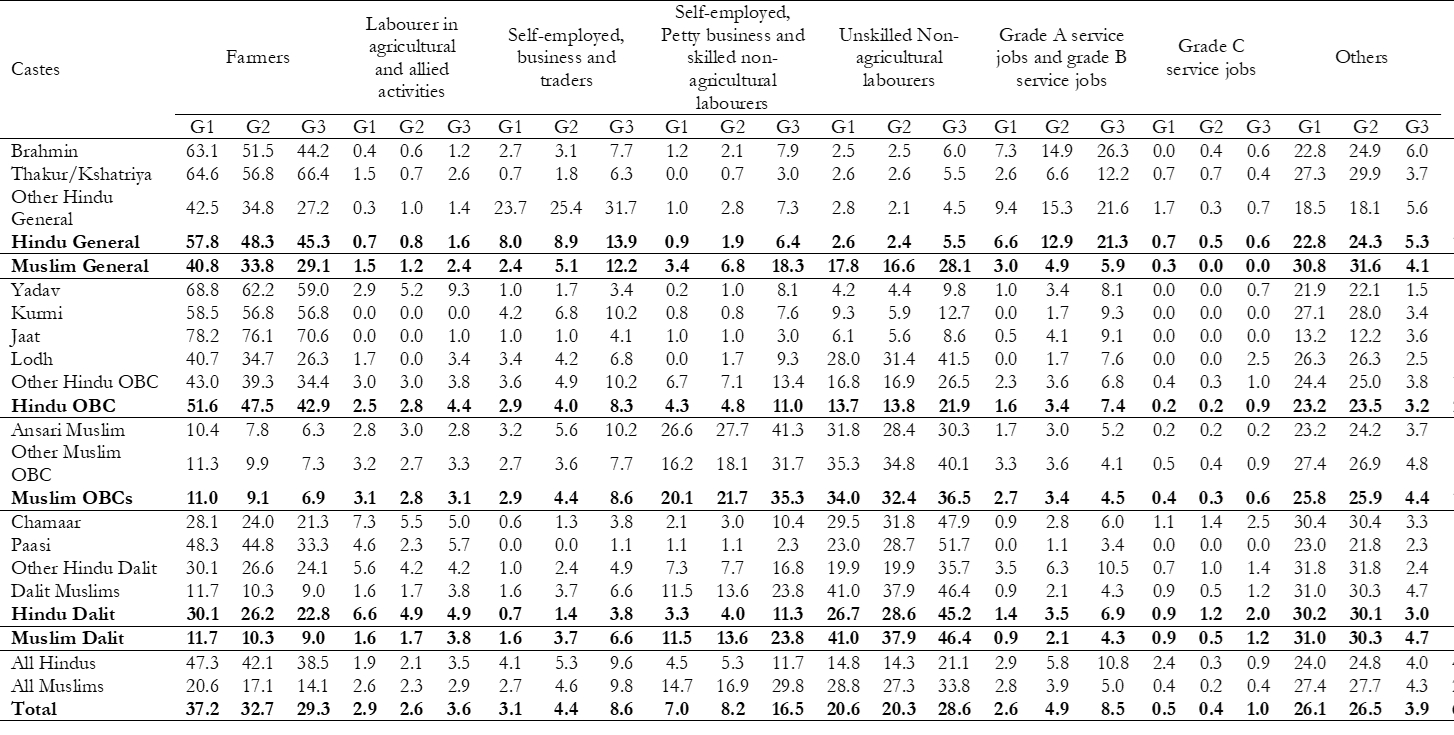

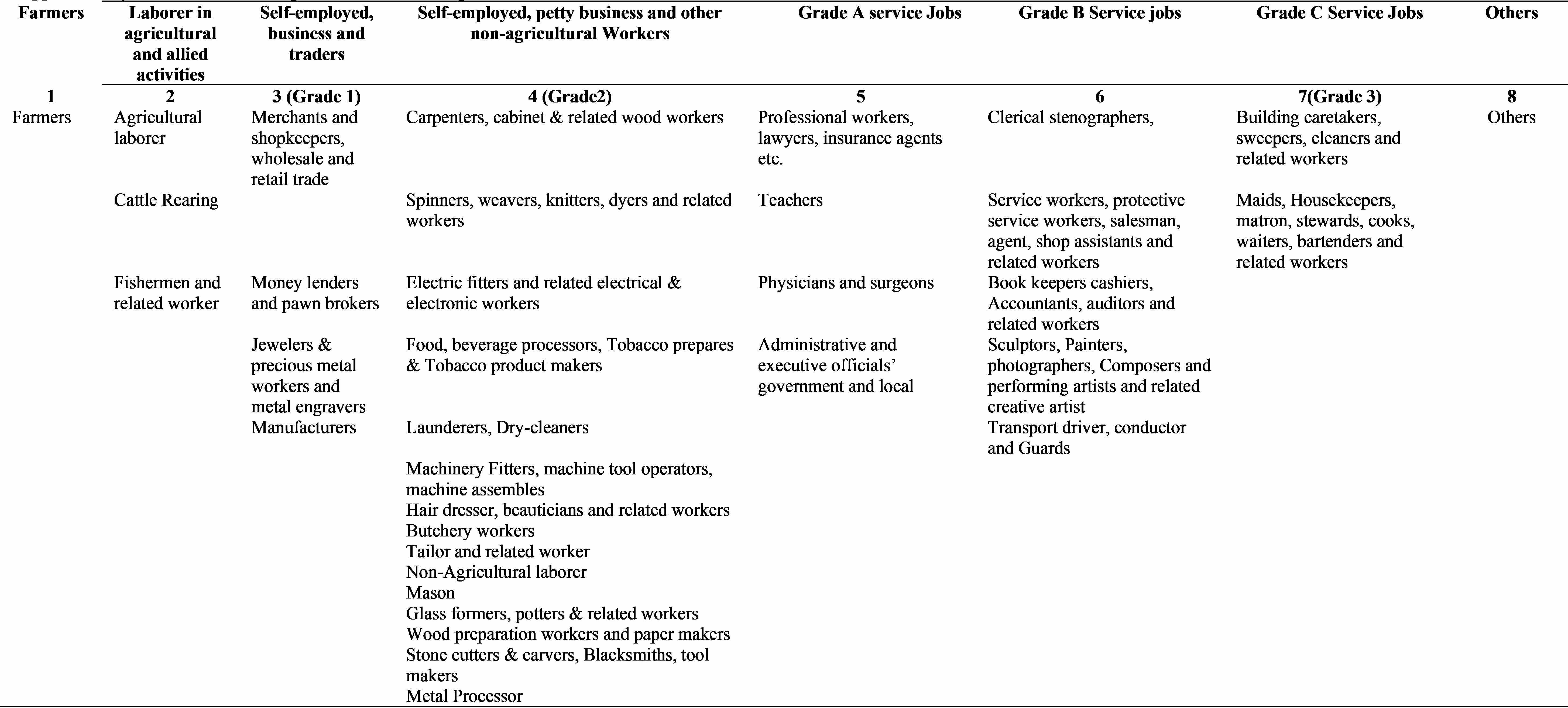

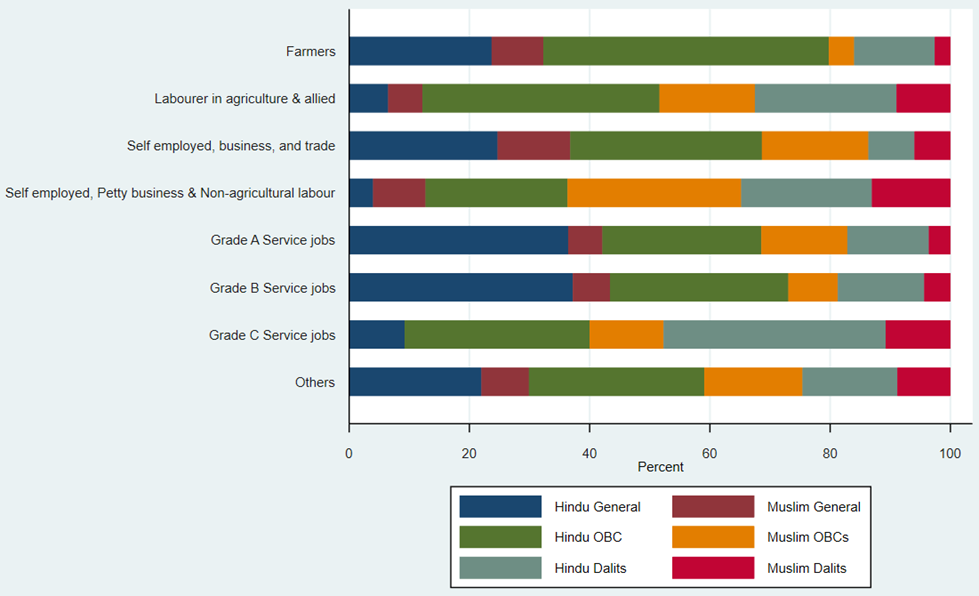

The occupational structure is highly segregated by caste, and this is still evident in the third generation, or the respondent’s generation (Figure 1). The occupational categories listed in the survey were farmers; labourers in agriculture and allied activities; self-employment: business and trade; self-employment: petty business; skilled non-agricultural labourer; unskilled non-agricultural labourer; Grade A service jobs; 1Grade A refers to administrative and executive officials, architects, engineers, doctors, working proprietors, directors, managers, social, biological, and physical scientists, lawyers, jurists, and such jobs, both in the private and public sectors. Grade B service jobs; 2Grade B includes teachers, clerical stenographers, nursing and medical health technicians, accountants, bookkeepers, telephone and computer operators, and similar jobs, again in both sectors. and Grade C service jobs. 3Grade C includes clerks, multi-tasking staff, stenographers, assistants, typists, telephone operators, primary teachers, havildars, constables, assistant sub-inspectors, technicians, mechanics, attendants, linemen, drivers, electricians, supervisors, cashiers, store keepers, chemists, sanitary inspectors, and so on in both sectors. (See Appendix Table A-4 for a detailed classification.)

Muslim OBCs and Hindu and Muslim Dalits together constituted an overwhelming proportion of petty businessmen and non-agricultural labourers.

The Hindu general caste group dominated Grade A and Grade B service jobs in both the public and private sectors, and they were also a major proportion of those working in large business and trade activities. Among Grade C jobs, Hindu Dalits were the single largest group. Muslim OBCs and Hindu and Muslim Dalits together constituted an overwhelming proportion of petty businessmen and non-agricultural labourers. Hindu general and Hindu OBCs were dominant as agricultural landowners across generations, leaving Dalits and Muslim OBCs far behind. Among agricultural labourers, Hindu OBCs and Dalits were dominant.

Figure 1: Occupational Segregation of Respondents by Broad Socio-Religious Groups

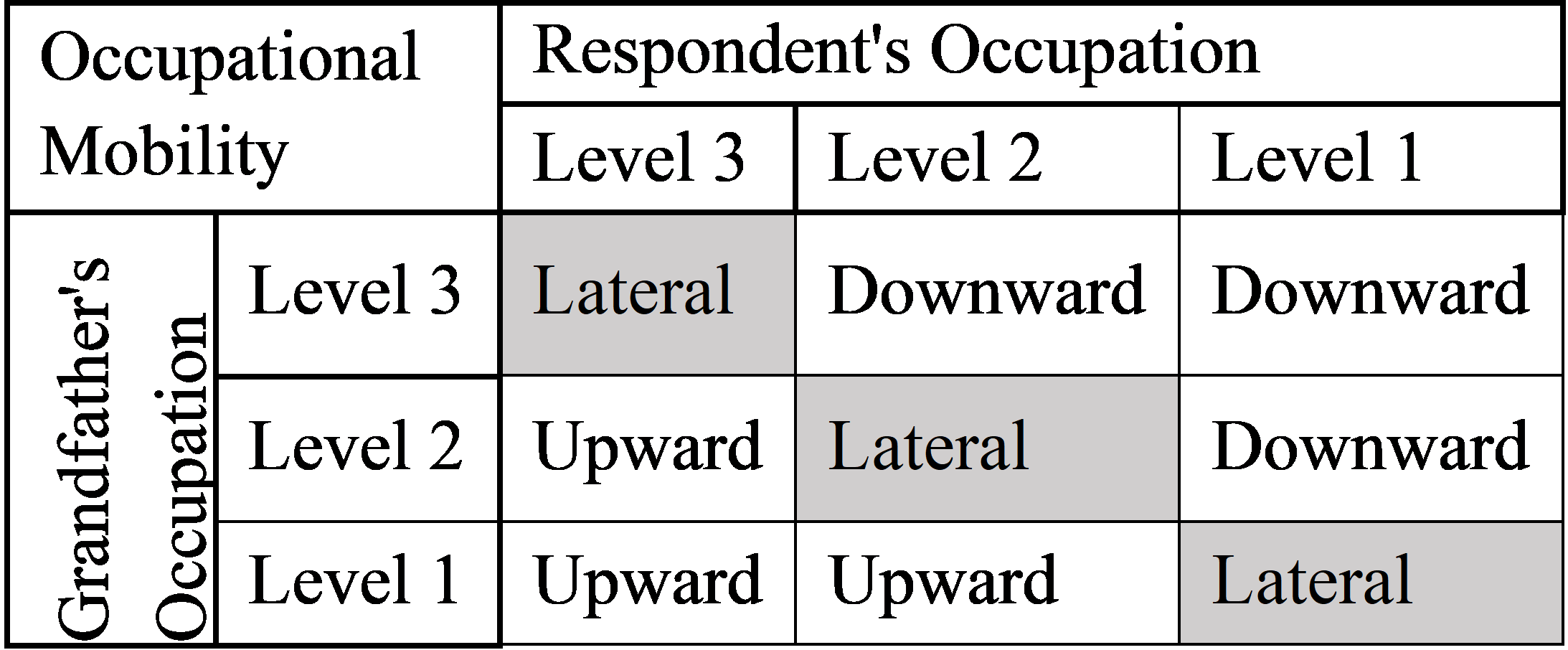

However, unless we understand whether mobility is upward, downward, or lateral, it will not tell us whether occupational mobility is benefiting a particular caste.

• Upward occupational mobility is a transition to higher status and higher paid employment compared to the occupational rank of their previous generations.

• Downward occupational mobility is a transition to lower status and lower paid employment compared to the occupational rank of their previous generations.

• Lateral occupational mobility is defined as a change of occupation within the same broad occupational class of their previous generations, indicating no change in social status or wage.

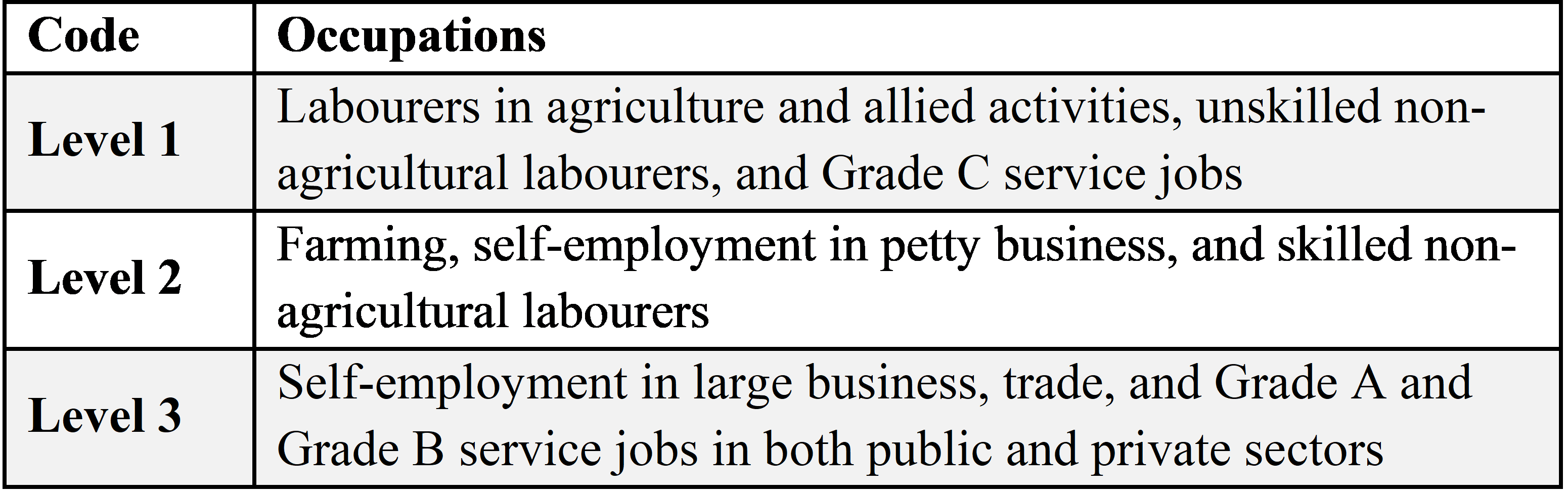

In our study, occupations are categorised into three occupational levels in a hierarchical order according to the expected wage and social status and social security attached to them—from Level 1 (lowest) to Level 3 (highest) (Table 1).

Table 1: Classification of Occupations

The Grade A and B service sectors and large-scale businesses occupy the highest position in the occupational hierarchy because they offer high-quality and high-paid jobs. These jobs demand higher educational qualifications and provide higher income, social security, and higher social status compared to other occupational groups.

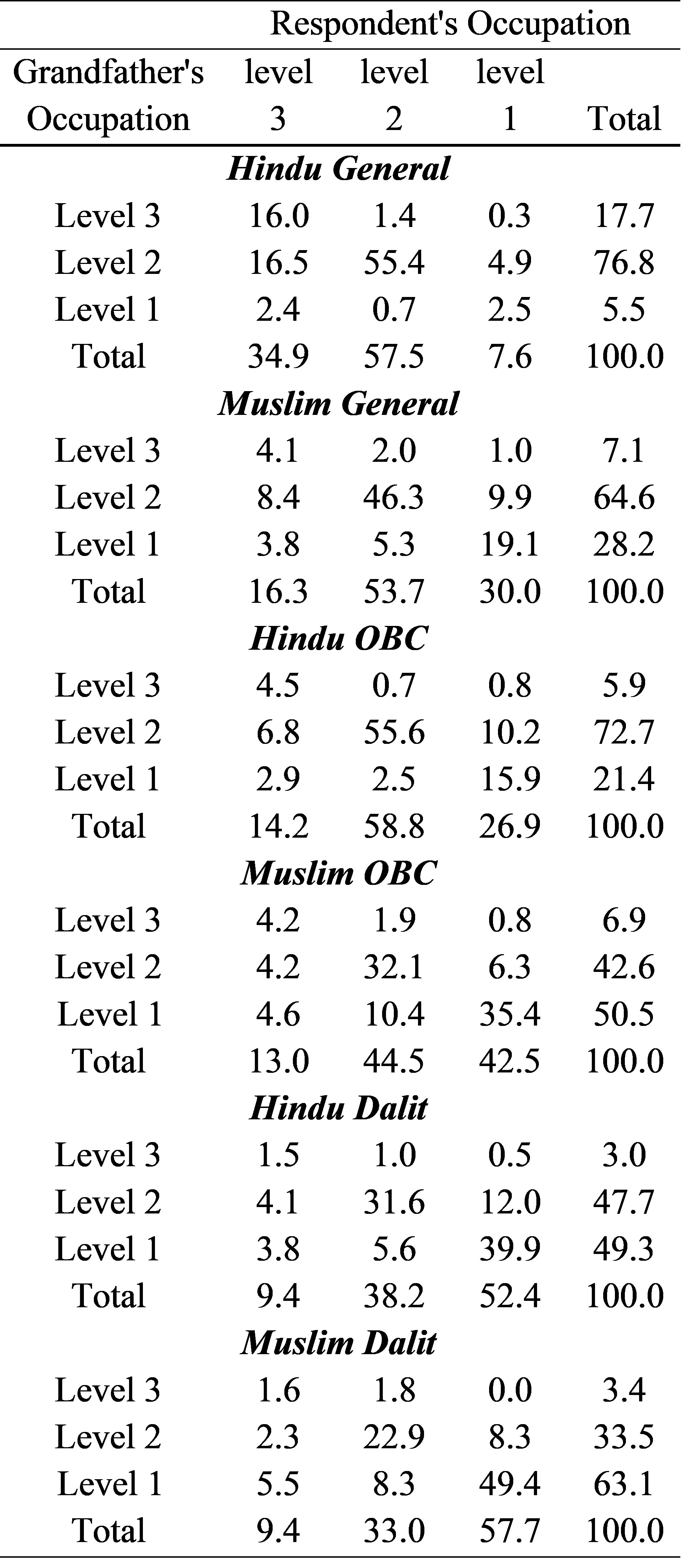

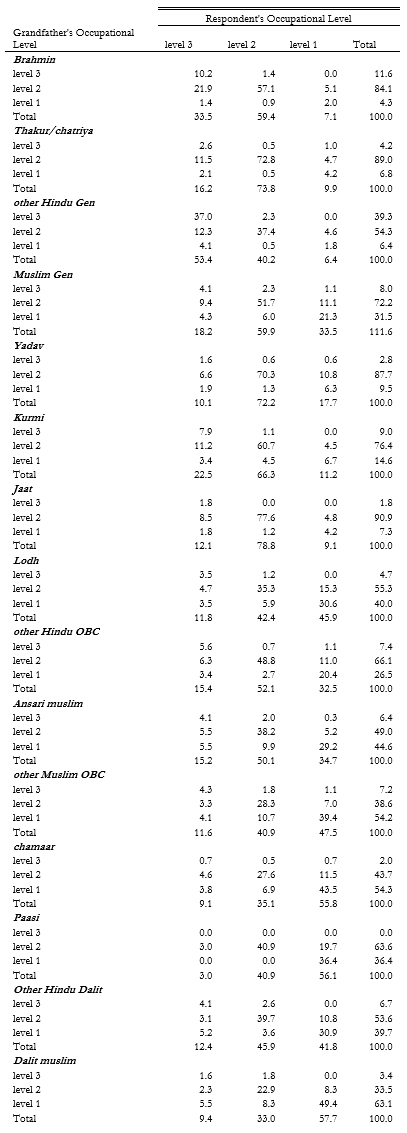

When we analyse the occupational level of respondents corresponding to that of their grandfathers, we can see the type of occupational mobility attained by them (Table 2).

Table 2: Transition Matrix – Occupational Mobility from Grandfather to Respondent

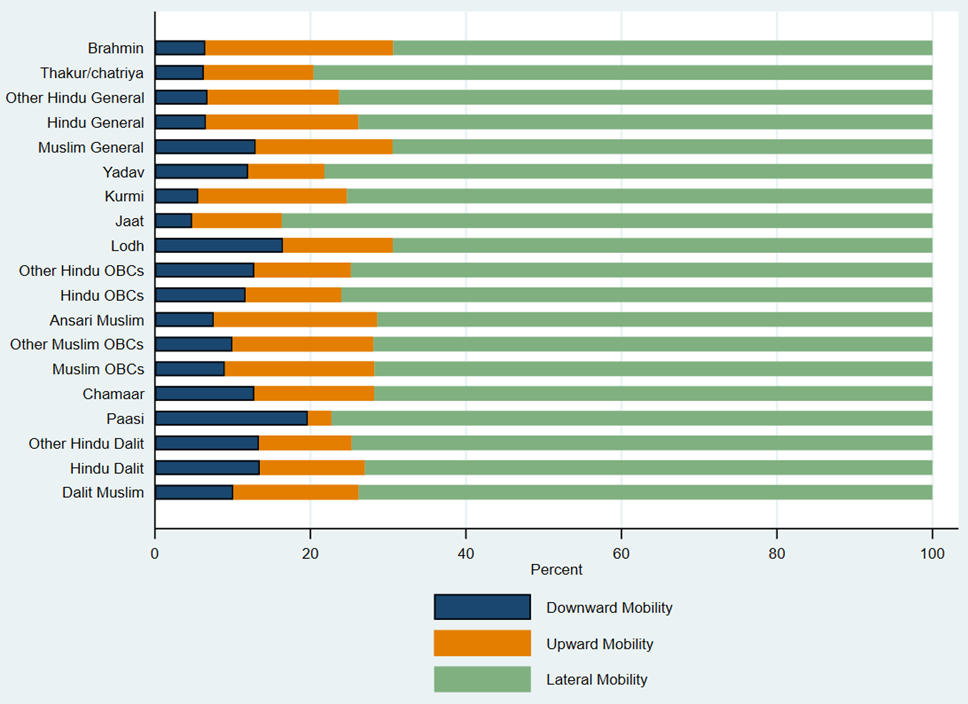

Figure 2 demonstrates the percentage distribution of downward, upward, and lateral occupational mobility from the grandfather’s generation to the respondent’s generation of each sub-caste and socio-religious group. The transition matrices from grandfather to respondent generations were made for all sub-castes and groups. The sum of the percentage values of all three possible downward occupational transitions for each sub-caste and socio-religious group represents the percentage of respondents experiencing downward mobility from the occupational rank of their grandfathers. Similarly, the percentage of respondents experiencing upward mobility from their grandfather’s occupational rank, as well as the percentage of respondents exhibiting lateral mobility or moving to other occupations in a similar rank as their grandfather’s occupation, were calculated and visualised across each sub-caste and socio-religious group (Appendix Table A-1).

The direction of mobility among Hindu and Muslim Dalits was more downward than upward, or approximately double the downward mobility observed among the upper Hindu castes. Upward occupational mobility was highest among Brahmins, more than any other sub-caste. The dominant direction of mobility for Hindu general castes as a whole was from medium-level jobs (skilled non-agricultural labour, farming, and so on) to highly paid jobs. They showed more than three times the mobility seen among Hindu OBCs and Hindu Dalits (Appendix Table A-1, with summary in Appendix Table A-2).

The level of upward mobility for Muslim OBCs was similar to Hindu general castes. But their direction of mobility was particularly from jobs requiring a low level of skills to ones needing medium-level skills, not to the highest levels of the occupational hierarchy. However, within Muslims, the upward mobility of Ansari Muslims was much more than their downward mobility. Among Hindu OBCs, Lodhs and Yadavs had a higher mobility to lower-level occupations. Kurmis and Jats had attained higher occupational levels than their grandfathers. Jats stood out for their high lateral mobility, driven by sustaining their presence in large-scale farming over successive generations.

Appendix Table A-1 shows the distribution of occupations within each sub-caste and socio-religious group in all three generations (G1-grandfather, G2-father, and G3-respondent).

From the grandfather’s generation to the respondent’s generation, Hindu OBCs had diversified into occupations such as self-employment in petty business (3% to 9%) and skilled non-agricultural labour (4% to 11%), and unskilled non-agricultural labour (14% to 22%). Interestingly, Hindu Dalits were the only group that showed a clear shift in their occupational structure—that is, they had withdrawn from agriculture both as farmers and labourers, but the direction of their mobility remained lateral. Their occupational diversification was moving more towards unskilled non-agricultural labour, with an increase of 18 percentage points over three generations.

Moving from the grandfather generation to the respondent generation, the relative gap in service sector jobs remained more or less the same between Hindu upper castes and Hindu OBCs, while it increased between Hindu OBCs and Muslim OBCs.

Among Muslims, OBCs and Dalits never had a significant presence in agriculture as they were more likely to be landless or have a small landholding (Tiwari et al. 2022). The largest share of their population remained in, or shifted to, unskilled non-agricultural labour, contributing to their downward and lateral mobility over generations. These two socio-religious groups also have an increased presence in petty business and skilled non-agricultural labour, but their diversification remains constrained.

Another key insight from Appendix Table A-2 is the rising gap in mobility between lower caste and higher caste groups over the generations. In the grandfather generation (G1), the difference between Brahmins and Jatav-Chamars in Grade A and B service jobs was 6.4 percentage points. This had risen to 20.3 percentage points in the respondent generation (G3), which suggested a three-fold increase in inter-caste inequalities in the occupational hierarchy. (Details in Appendix Table A-1).

Similarly, moving from the grandfather generation to the respondent generation, the relative gap in service sector jobs remained more or less the same between Hindu upper castes and Hindu OBCs, while it increased between Hindu OBCs and Muslim OBCs. Considering the large-scale business and trading sector, the gap between Muslim general castes and Muslim Dalits rose from 0.8 percentage points in the first generation to 5.6 percentage points in the third generation.

Figure 2: Occupational Mobility from Grandfather’s to Respondent’s Generation by Sub-Castes and Socio-Religious Groups

Conclusions and implications

Despite more than six decades of welfare policies and major political mobilisation among lower castes in Uttar Pradesh, our findings suggest marginal lateral mobility (that is, moving across occupations of a similar nature or rank) among Dalits and no significant mobility among OBCs. The huge caste segregation in occupations affected their labour market outcomes and contributed to persisting social and economic inequalities across castes.

Although mobility was universal across the castes with socio-economic transition, most of the upper castes ascended the social ladder to attain better jobs in the service and business sectors (high-paid jobs with social security). This was more than the shift of lower castes to unskilled labour and manual jobs in the Grade C category (low-paid jobs with least social security). The upper castes were retreating from lower income occupations while the lower castes among both Hindus and Muslims filled the vacancies left by them. The inter-generational predominance of Hindu general castes in Grade A and B service sector jobs, business, and trading demonstrated that the gap in the level of inter-generational mobility between upper-caste groups and marginalised caste groups had widened over successive generations.

With transition in the Indian economy, individuals aspired to secure, highly paid service occupations to attain a relatively higher socio-economic position and living standards. However, inter-generational occupational mobility among lower caste groups was largely restricted to low-paid, low-skilled jobs, as opportunities for advancement in later generations remained limited. Even though there was substantial mobility of the respondent’s generation of Muslim general castes towards large-scale business and trading, their under-representation in highly paid service jobs over three generations had to be noted. Thus, the ongoing socio-economic transition in India induces more economic segregation than earlier and leads to unequal economic outcomes and well-being. This is something that needs to be addressed through relevant social and economic policies.

A synthesis of our analyses and previous evidence suggests that the overall gap between marginalised socio-religious groups and Hindu upper castes is still very high.

The increasing dominance of caste in Indian politics is because of continued disparities in socio-economic conditions and labour markets. The recent conflicts between Marathas and other OBC groups in Maharashtra, Jats versus others in Haryana, Yadavs versus other OBCs in Uttar Pradesh, Malas versus Madigas in Telangana, and Kapus versus Khammas in Andhra Pradesh point to the growing unrest within broad social groups (Deshpande and Ramachandran 2017). However, differences within broad social groups should not make us ignore the larger gaps between historically marginalised social groups and socially and economically privileged upper castes.

A study conducted in Allahabad by Gupta Aggarwal et al. (2015) highlighted the dominance of upper-caste groups in “positions of power and influence”, based on data collected from various educational institutions, administrative bodies, judicial institutions, trade unions, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Another study revealed a systemic under-representation of backward castes in the list of selected candidates for public service recruitments (Kumar et al. 2020). Moreover, the exclusion of Dalit Muslims from the official list of SCs prevents them from securing the benefits of the affirmative policy.

A synthesis of our analyses and previous evidence (Tiwari et al. 2022; Trivedi et al. 2016b) suggests that the overall gap between marginalised socio-religious groups and Hindu upper castes is still very high. However, more research needs to be conducted on wider indicators at an all-India level to stimulate a debate and find policy prescriptions. Unless a caste census is carried out with the general census, it will be very difficult to accurately map sub-caste hierarchies and effectively monitor socio-economic development indicators.

Rukmi Pradeep is a doctoral student at the International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai. Srinivas Goli is an associate professor at the International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai.