The past is immutable and time’s arrow moves only one way. History cannot be altered, but a nation and its citizens can choose how to recall past times. This freedom is an unconstrained individual right, but always influenced by popular culture and official guidance. Governments often decide how history is remembered and recorded in ways that reflect their roadmap for the future.

The book’s subtitle leaves the subtext unstated—that every view is valuable, apart perhaps, from those advanced with the explicitly divisive purpose of demonising a faith.

A busy and prosperous city today, Hyderabad was at one time a Muslim Nizam’s kingdom. Its accession to India was contentious, but overshadowed since in the annals of the Indian Union by Jammu and Kashmir. A polyglot province with an Urdu syncretism that linked at least three different language groups, Hyderabad was in 1948 the location of an armed confrontation that brought it in line with the object of Indian unity. As a city, it has had recurrent bouts of communal violence, but is now associated with a relaxed and laidback culture and rich culinary traditions. It is also a centre of India’s storied software industry.

When the troubled past is behind us and the present is secure in the embrace of modernity, why does India as a nation restore certain aspects of history to public memory?

As this anthology of diverse perspectives on the 1948 events records, the first known effort in this cause was by Omar Khalidi, an archivist who published what were believed to be extracts from the report of the Pandit Sundarlal Committee, assigned by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to address certain troubling aspects of the army action in Hyderabad. Years later, eminent scholar A.G. Noorani obtained fuller access to the report, engaging Khalidi in friendly debate in the fortnightly magazine Frontline. In 2013, the BBC released a news capsule titled “India’s Hidden Massacre”, triggering, as this book notes, a “minor avalanche of bitter memories”.

“One Period, Many Views” says the subtitle to this anthology that brings on record perceptions from many disciplines. The subtext here is left unstated—that every view is valuable, apart perhaps from those advanced with the explicitly divisive purpose of demonising a faith. And that seemed precisely the object in 2022 when India’s government resolved that Hyderabad’s “liberation” on 17 September 1948 would be a national day of observance.

Sundarlal Committee report

If building resistance to divisive views is about unearthing forgotten history, this volume performs an invaluable function. History, as officially promoted, remembers the army action in Hyderabad as brief but decisive, and its aftermath as peaceful and orderly. But the Sundarlal Committee, whose report is excerpted here, estimated that between 27,000 and 40,000 people could have been killed in the violent aftermath.

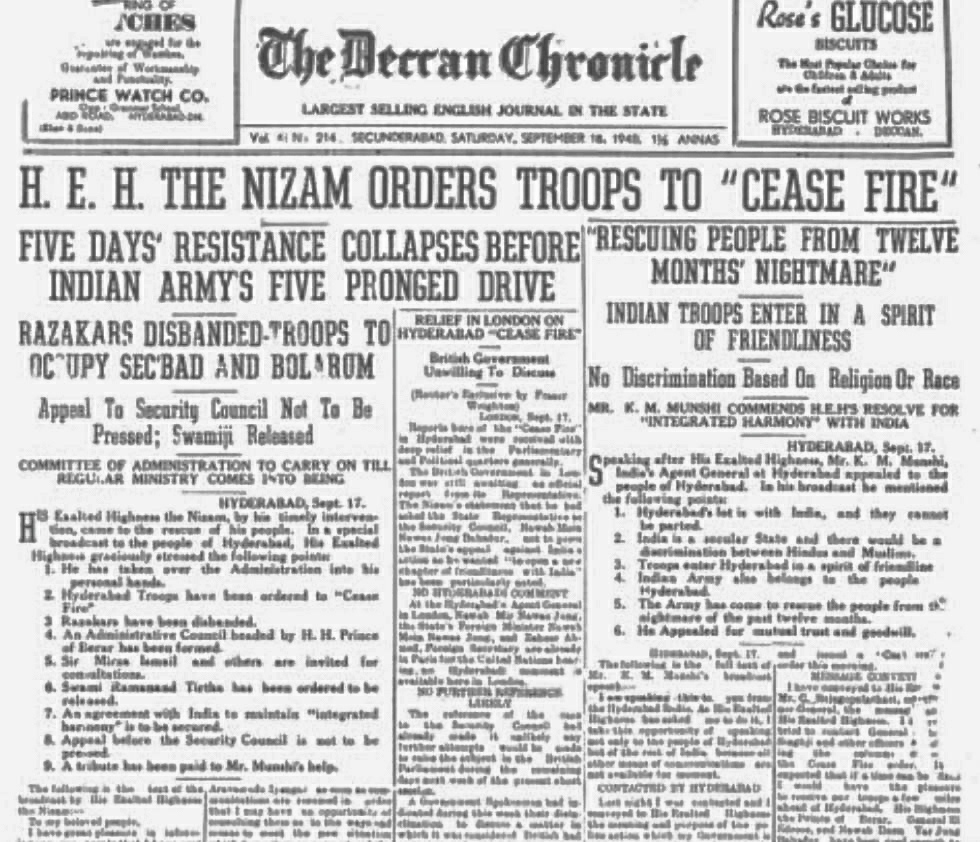

After an enquiry spread over three weeks, the committee concluded that of the 16 districts in the state, only three remained “practically, though not wholly, free of communal trouble”. The worst affected were “Osmanabad, Gulbarga, Bidar and Nander, in which the number of people killed during and after the police action was not less, if not more, than 18,000”. The violence began before the army operation when bands of marauding Razakars, the militia assembled by the Majlis-e-Ittehadul-Muslimeen (hereafter, Ittehad), were let loose through the state. Functioning entirely outside the control of the armed forces of the state, this militia was born in the fraught environment of the 1940s, when uncertainty over Hyderabad’s future loomed larger every day.

After the army operation, the committee records “communal frenzy did not exhaust itself in murder alone”—“Rape, abduction of women (sometimes out of the state to Indian towns such as Sholapur and Nagpur), loot, arson, desecration of mosques, forcible conversions, seizure of houses and lands, followed or accompanied the killing”. And those who bore the brunt of the violence “were Muslims who formed a hopeless minority in rural areas”.

Abdur Rahman Khan was a 12-year-old living in the town of Yadgir (today in Karnataka), who set off for safety with his family soon after army units started moving. There was only one railway service available under an Indian blockade of the province, and from his train, the young boy saw a propeller plane swoop down with its engine cut and drop a bomb. His train may have been the target, but the bomb fell on a bus packed with passengers, “killing and wounding dozens”. In his piece, reproduced in this volume, he wonders if that attack might not be a “war crime”.

After an enquiry spread over three weeks, the committee concluded that of the 16 districts in the state, only three remained “practically, though not wholly, free of communal trouble”.

Omar Khalidi’s contribution excavates the life and work of Maulana Sayyid Abu’l Ala Mawdudi, a scholar of religion and influential writer in Urdu. Born in Aurangabad, then part of Hyderabad (a town in Maharashtra recently renamed Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar), Mawdudi was well travelled and widely read. A political pragmatist, he thought the Nizam had embarked upon an unwinnable strategy. Mawdudi had a set of negotiating points prepared for the Nizam’s attention, all involving the honourable treatment of the Muslim population of Hyderabad after accession. But, the Ittehad, a political movement of the state’s Muslims, by making maximalist demands on the Nizam, ensured that a reasonable outcome remained elusive.

Examining all available sources, Khalidi concludes that the folly and indecision of the Nizam led, after the army action, to the killing of “nearly 200,000 Muslims (who) were butchered in an orgy of violence directed by the Congress Party gangs”. Despite his role in uncovering the Sundarlal Committee report, Khalidi uses certain unidentified sources to arrive at the far higher estimate of death and devastation. Scholarly works since then (see here and here), have recorded broadly concurring numbers.

Closure on this question remains elusive, and the reasons are clear. As Noorani has recorded in his writings (a curious omission in this volume), the findings of the Sundarlal Committee, though in full conformity with the mandate assigned by Prime Minister Nehru, were repudiated by Home Minister Vallabhbhai Patel. Patel was reported to have angrily questioned the committee’s credentials and attacked its supposed focus on the aftermath of the army action while glossing over the atrocities of the Razakars. These aspersions, as Noorani has recorded “were simply untrue and … unworthy of Sardar Patel”, since the Sundarlal report was a “balanced” document that had strong words of censure for the Razakars.

Critiquing Nationalist Theology

Patel’s inattention to the loss of Muslim life and his exaggeration of Razakar atrocities was the unstated premise of nationalist theology for long. From 2014, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi assumed power, the violence has been embraced as a defining feature of Hyderabad’s, and indeed the nation’s, identity. Home Minister Amit Shah put it with abundant clarity at the inaugural observance of 17 September as “Hyderabad Liberation Day”. He spoke of how the province had, even after India’s independence, suffered 399 days of the Nizam’s tyranny and Razakar terror. It was an instinct for appeasing religious fanatics—a character flaw all other parties shared—that had led to India’s youth not knowing of “this great day”. Yet, from then on, it would be inscribed indelibly into India’s calendar of nationalist celebrations.

This volume assembles sufficient documentation to dismantle this divisive agenda. Though ruled by a Muslim potentate, the composition of the “ruling classes” of Hyderabad, Javeed Alam writes, was “of a mixed nature”. In a state where 88% of the population was of the Hindu faith, Muslims held two-thirds of all jobs in the administrative departments, often even more. At the level of village officers, of which there were over 90,000 in the 1930s, Hindus had almost exclusive control. Over 80% of the “rentier-landowners were Hindus”, and for all the Muslim dominance in the administration, industry and trade remained Hindu monopolies.

The Arya Samaj and the Hindu Mahasabha made their entry to Hyderabad during this time. Representing the growing embattlement of Muslim sensibility, the Ittehad too sprang up.

Hyderabad’s social fabric was held together by many threads of interdependence. As M.A. Moid and A. Suneetha point out in their contribution, religious neutrality was firmly upheld under the Nizam’s rule, both through institutional means and elite personal example. Far from being untrammelled, monarchical authority was qualified by the presence of 14 samasthanams or local kingdoms, almost all of them ruled by Hindu dynasties with privileges dating back to the Kakatiya and Vijayanagar empires. A ministry on religious affairs, dating to the latter half of the 19th century, “closely monitored new religious structures, festivities and procession routes”. The Nizam and the samasthanam kings were careful to maintain scrupulous public appearances of respect for all faiths.

The 1920s were a time of proliferating identity politics in India, and in Hyderabad as well. The Congress, the main vehicle of the nationalist quest, had an official policy of non-intervention in princely states, but other all-India bodies, including those with a powerful sectarian slant, were eager to intervene. The Arya Samaj and the Hindu Mahasabha made their entry to Hyderabad during this time. Representing the growing embattlement of Muslim sensibility, the Ittehad too sprang up, establishing a ready rapport with the All-India Muslim League in British India.

In 1932, as Moid and Suneetha recount, the Ittehad engaged the Mahasabha in a public debate over the alleged “mistreatment of Hindus at the hands of Muslims”. The Ittehad questioned the supposed facts adduced by the Mahasabha about the exclusion of Hindus from all administrative tiers, referred to certain special rights of inheritance they enjoyed, and their dominance in trade and finance. On the ideological plane, the Ittehad contested the Mahasabha’s claim to speak on behalf of the wide category of “Hindus”. As it said in a pamphlet brought out in 1932, “The claim of 85% Hindus by the Hindu Mahasabha is also a fraud. When they want to attain benefit, they include all those also within their ranks, whose shadow makes them unclean.”

The Endgame

This volume includes an extract from the memoirs of P.R. Venkatswamy, a Dalit leader of the time, who saw the pitfalls of alliance with the Mahasabha and the Arya Samaj, and sought an autonomous line of action. He and Shyam Sundar, an associate, gained the unflattering epithet of “Ittehad Hindus” from K.M. Munshi, who oversaw the army action as Agent-General of the Indian Union in Hyderabad and today occupies a stellar place in the Hindutva revisionism of history. However, in parallel with the valiant but ultimately losing hand that B.R. Ambedkar was playing in national politics, the Dalit and depressed classes in Hyderabad never quite managed to secure an autonomous position within the scheme of representative politics.

As a longish extract from the work of Australian scholar Lucien Benichou explains, for all the promises made by the Nizam to move towards “responsible government”, there was very little progress in evidence in 1938. That is when the Arya Samaj and the Hindu Mahasabha, drawing on resources from outside the province, launched their agitation to save Hyderabad from itself. The Congress by this time had a presence in the shape of the Hyderabad State Congress, and joined in the movement, which deployed a whole range of emotive tropes, from Hindu temples being vandalised to mass atrocities against people of the faith.

After Jung’s death in 1944 by poisoning, his successor Qasim Razvi took a more intransigent line, resisting even the counsels of the Nizam and his court, and setting up the Razakars to enforce his diktat.

The Nizam responded with magnanimity, inviting one of the Shankaracharyas to tour the state and see for himself what the situation of the Hindu population was. And at the end of his extensive tour, the Shankaracharya concluded that the circumstances he had been invited to investigate did not exist. There simply was no organised atmosphere of repression against the Hindu majority in Hyderabad. The national leadership of the Congress, meanwhile, had been briefed by Padmaja Naidu about the Hyderabad unit’s dangerous turn towards communal adventurism, which she feared had earned it “the active resentment of the Muslims and the depressed classes”.

As independence and decision time approached, the Congress leadership adopted the posture that Hyderabad should accede to the Indian Union on exactly the terms offered to other states—a message that the Mahasabha and Arya Samaj began to underline with violence and disruption in several districts. The Ittehad had grown in terms of popular support in this time. Under Bahadur Yar Jung’s leadership, it sought to align its politics with the Muslim League under Mohammad Ali Jinnah. But after Jung’s death in 1944 by poisoning, his successor Qasim Razvi took a more intransigent line, resisting even the counsels of the Nizam and his court, and setting up the Razakars to enforce his diktat.

Contributions to the volume by H. Montgomery Hyde, the biographer of Walter Monckton, principal negotiator for the Nizam, and Nawab Ali Yavar Jung, scion of a storied Hyderabad family who held various ministerial portfolios, identify Razvi as a baneful influence on the negotiating process. Mohammad Hyder, collector of Osmanabad district during the critical years, records how Razvi called him at a particularly tense time in the negotiations and issued a chilling warning of insurrection. Hyder was, as recorded in a brief excerpt from his book, “flabbergasted” and hugely relieved when Razvi ordered his forces to stand down. On 16 September, the day before Hyderabad’s surrender, he went to meet Razvi and found him in a “contemplative mood”, his usual mood of “supreme self-confidence” absent.

Razvi was arrested soon after the army action and spent nine years in prison before being exiled to Pakistan. Hyder, despite what he believed to be an excellent record in the civil service and reasonable expectations of reinstatement, also suffered imprisonment on concocted charges before being dismissed.

In a section of his book, published many years later (partially excerpted in this volume), Hyder records how in personal meetings Razvi struck him as a pragmatist, a skilled debater with an answer to every possible point. Beyond the binary choice then spoken of—either independence or accession to India—Hyder sought Razvi’s views on political reforms that introduced “responsible government” based on the principle of “majority representation”. Razvi’s response was steeped in realpolitik. “I see much to admire in Hindu social reform,” he said. “I freely admit they are more advanced educationally and more sophisticated politically and better off economically. We rule, they own! It’s a good arrangement, and they know it!”

The Nizam’s often quirky decisions led in little time to a full-fledged blockade by India. From then on, events moved swiftly towards the army action and its brutal aftermath.

Excerpts from Monckton’s biography speak of the tortuous course of negotiations between Hyderabad and the Indian Union, and the frustrations he encountered at the Nizam’s paralysis. A “standstill” was agreed in November 1947, which involved a commitment by both sides to cease their disruptive campaigns. The street proved unresponsive to the Nizam’s demands, and his own often quirky decisions led in little time to a full-fledged blockade by India. From then on, events moved swiftly towards the army action and its brutal aftermath.

Conclusions

What we learn from this volume is that there was (and still is) enough blame to go around for the tragic events of September 1948. And that the polarisation of opinion between accession and independence was not reflective of the Hindu-Muslim divide. Many among the depressed classes supported the option of independence, though their voices were drowned in the cacophony. The history of Hyderabad and indeed, of India since then, displays frequent episodes when the demonisation of the Muslim faith has been a strategy of cementing solidarities across caste and class divisions.

That is the purpose, all but overtly stated, of the new revisionism on the history of Hyderabad’s accession. How far that will succeed will depend upon strategic political choices made by the people of the city and its wider region, particularly those who have not had much say in how their histories are created and written.

Sukumar Muralidharan is an independent researcher and journalist based in the Delhi-NCR.