When I walked into my seminar, “Gandhi in the World”, at the beginning of last semester, I had not expected to learn so much from my students about M.K. Gandhi’s image as I did. I was certain that I would be the one imparting knowledge about him as a historical figure. I had not taught a course on Gandhi in more than two decades and during that time, unbeknownst to me (a faithfully analog scholar), he had a acquired a vibrant, and mostly negative, online persona, which my students were deeply engaged with. And they did not seem to shy away from sharing these ideas from the online world in the classroom. This should not have surprised me, not only because they are a generation that lives online, but also because Gandhi’s life, replete with experiments of all kinds (some morally questionable), offers a perfect opportunity for this generation to question his greatness.

Shifting Images

Every generation judges and renews its interest in historical figures on the basis of the zeitgeist and the needs of the historical moment. Gandhi and his legacy are no exception. Immediately after his violent death at the hands of an assassin in 1948, which was in stark contrast to his lifelong commitment to non-violence, Gandhi was canonised as the Father of the Nation in India and as a saintly proponent of pacifism in the West. Since Gandhi’s ideas and activities offered a concrete methodology against oppression, he and his methods became a source of inspiration for anti-colonial movements worldwide, including the civil rights movement in the United States and the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

Since the film [Gandhi] hewed closely to the Indian nationalist narrative, portraying Gandhi as the movement’s founder, depicting Jawaharlal Nehru in a positive light, and casting figures like Muhammad Ali Jinnah as villains, it was popular in India.

Each of these movements utilised Gandhi in its own way and for its own purposes. For instance, American civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. framed Gandhi’s non-violent method of resistance in a Christian context, thereby creating an indelible link between Gandhi and Christ for Americans. Gandhi had himself encouraged this association in the 1930s to garner American attention for the Indian nationalist cause. So powerful was this connection that the first time I taught a course on Gandhi in America two decades ago, many of my students were only interested in exploring the relationship between Christianity and Gandhian thought.

Richard Attenborough’s film Gandhi, released in 1982, brought fresh attention to Gandhi as a historical figure and leader of a non-violent anti-colonial struggle against the greatest European empire. Since the film hewed closely to the Indian nationalist narrative, portraying Gandhi as the movement’s founder, depicting Jawaharlal Nehru in a positive light, and casting figures like Muhammad Ali Jinnah as villains, it was popular in India (we were annually subjected to it in school on Gandhi’s birth anniversary). Initially, Western reviews of the film, and the man whose life it depicted, were positive, highlighting Gandhi’s saintliness and his ability to organise a mass movement against the British Empire that eventually led to India’s independence. But it also laid the historical Gandhi open to criticism.

This was most apparent in Richard Grenier’s March 1983 review of the film in Commentary, entitled “The Gandhi Nobody Knows”. Grenier, a neo-conservative columnist for the Washington Times, took exception to the fact that the film presented itself as the true story of Gandhi the historical figure, when, in his view, it was no more than a “large, pious, historical morality tale centered on a saintly, sanitized Mahatma”, which occluded his defects so as not to diminish the didactic message of his pure, saintly life.

He thus took it upon himself to dismantle the film’s portrayal of Gandhi as anti-racist, anti-colonial, and pacifist, often in a brutally sardonic tone, by focusing on Gandhi’s inconsistencies and tyrannical qualities. His justifiable critiques of the film—that it was a “paid political advertisement” for India and its nationalist narrative, for instance—were interlaced with ad hominem attacks on Gandhi’s “Hindu” character and a celebration of the fairness of the British colonial state’s policies in India. The review thus indicted the film, Gandhi, and, by drawing on the usual tropes about India and Indians—and inventing some—the whole of Indian civilisation!

Social Media on Gandhi

Perhaps for this reason, Gernier’s review has had an expected afterlife online. Its free accessibility has made it a rich source for detractors of Gandhi in particular. And Gandhi is unfashionable in the contemporary moment. His emphasis on moderation and compromise are of no use to an age defined by extremes, where courting them is not just acceptable but the norm.

Grenier’s story about Gandhi—as told to him by a friend “who had gone to India many times and even gone to the trouble of learning Hindi”—denying penicillin to his dying wife has found resonance in the online world.

The Left and Right across the world converge in their dislike of Gandhi. The Left, especially the younger generation, despises him for his ostensible conservatism on issues of gender and caste, while the Right wants to knock him off his pedestal because his advocacy of non-violence and pluralism stands in stark contrast to their core belief of India as a militaristic Hindu nation. (In contemporary India, Gandhi has been reduced to an outline of his self, a mere symbol for the government’s Swachh Bharat campaign.)

Gandhi’s 150th birth anniversary in 2019 provided the occasion for a gathering of these forces online as they sought to systematically tarnish his legacy. The detractors drew heavily on Grenier’s review, sometimes quoting it verbatim, without acknowledging the source and presenting its ideas as true facts about Gandhi. Grenier’s story about Gandhi—as told to him by a friend “who had gone to India many times and even gone to the trouble of learning Hindi”—denying penicillin to his dying wife has found special resonance in the online world.

Slandering Gandhi has now become a veritable industry on TikTok, centering around three main issues—his alleged emotional and physical abuse of his wife and his retrogressive views on women more generally; his racist ideas, apparent during his time in South Africa; and his sexual proclivities, encapsulated in testing his powers of sexual abstinence by lying naked with his grand-niece. For Gen Z, any one of this trinity of sins—misogyny, racism, and pedophilia—is enough to cancel an individual, but that Gandhi displayed all three renders him forever a persona non-grata.

Of these sins, his sexual experiments cast the longest shadow and have spawned the most pernicious memes, including this on Instagram that one of my students shared with the class—a photograph of Gandhi leaning into his grand-niece, with the following words splashed across the top: “Din Mein Salt, Raat Mein Assault” (Salt During the Day, Assault at Night). A single phrase reduces Gandhi to a pedophile and rapist, while undermining one of the most powerful non-violent movements against colonial authority launched anywhere in the world.

Lessons

Thus it happened that when I asked my seminar (comprising Caucasians, some Latinos, and a couple of heritage students from India and the Middle East) on the first day what they knew about Gandhi, they did not immediately say that he was a political leader, a proponent of non-violence, saintly, and so on. Instead, they appeared sceptical until one of them finally gave voice to their collective feelings—why is Gandhi considered so great if he was a sexual pervert?

As I told the students, Gandhi never shied away from criticism in his lifetime; indeed, he welcomed it, engaged with it, and tried to make changes in his life based on it.

The question hung in the air as I considered how to respond, especially since at that time I did not have a clear idea regarding the origin of these sentiments. It became clearer after I asked them to explain, and they began to unravel the details about the videos on TikTok and the memes on Instagram that presented Gandhi’s flaws as hidden facts revealed for the first time. Although these images and videos were often posted and circulated by young Indians or Indian Americans to challenge the older generation’s portrayal of Gandhi as a saintly figure, young people regardless of race appeared to consume and usually believe them. They also appeared to have no knowledge of Grenier’s review as the source of these ideas, which I myself discovered after some digging.

I realised that I had a choice: I could either tackle these issues head on or just as easily dismiss them, labelling them as misinformation spread on social media. I decided to take the former route, because after all, that is what Gandhi would have done. As I told the students, Gandhi never shied away from criticism in his lifetime; indeed, he welcomed it, engaged with it, and tried to make changes in his life based on it. For him, life was a series of experiments in which to err was natural, and he erred often, sometimes learning from his mistakes and sometimes not. He was also quite conscious of his public image and sought to present himself in particular ways at different moments of his political career.

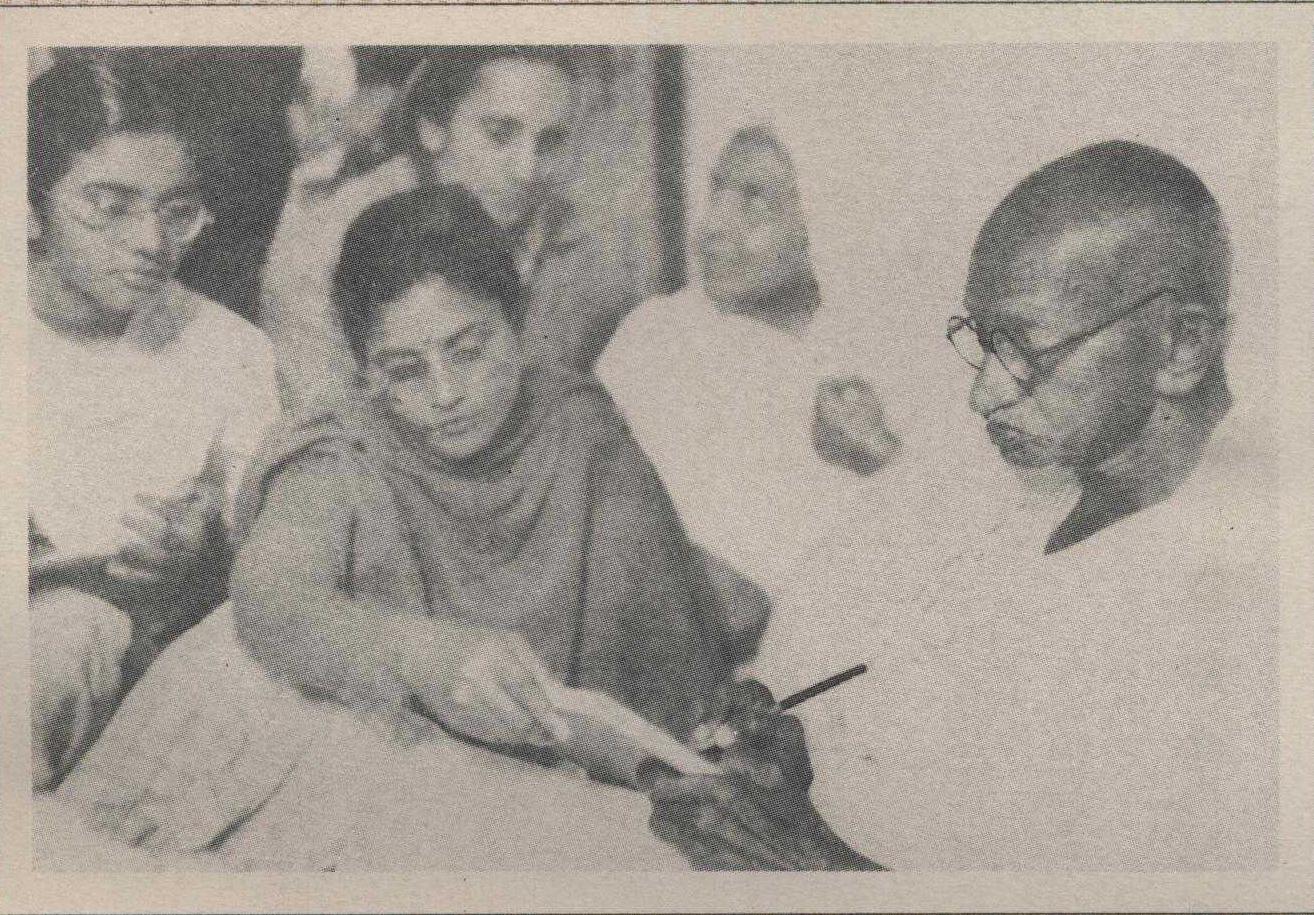

For instance, from 1925 to 1929, Gandhi wrote his autobiography in Gujarati in instalments that were published over the course of 166 weeks in the journal Navjivan, followed by English translations in Young India. He invited readers to comment on and even critique his life story as well as his recollections. And many did, some even harshly. Gandhi embraced and responded to each challenge publicly in the pages of the journals, even if he did not necessarily change the narrative of the autobiography (Suhrud 2018: 16–21). The autobiography itself, later published in the form of a book entitled An Autobiography, Or the Story of My Experiments with Truth, is an open discussion of his struggles to overcome his baser instincts in his journey towards spiritual self-realisation. As he wrote in its introduction, “I hope to acquaint the reader fully with all my faults and errors. My purpose is to describe experiments in the science of satyagraha, not to say how good I am” (2018: 49).

Fortunately, the last two decades have also seen the publication of English translations of Gandhi’s Gujarati writings, the writings of people surrounding him, and more complex biographies of him and his wife, Kasturba, all of which are available for use in the classroom. Books such as Geraldine Forbes’ Lost Letters and Feminist History and Tridip Suhrud’s Diary of Manu Gandhi (in two volumes), among many others, allowed us to more productively navigate the complex terrain of Gandhian thought and action through his lifetime.

Many of the students … wrote about Gandhi’s evolving ideas on women, due in large part to his engagement with a variety of women from across social strata and different parts of the world through the course of his life.

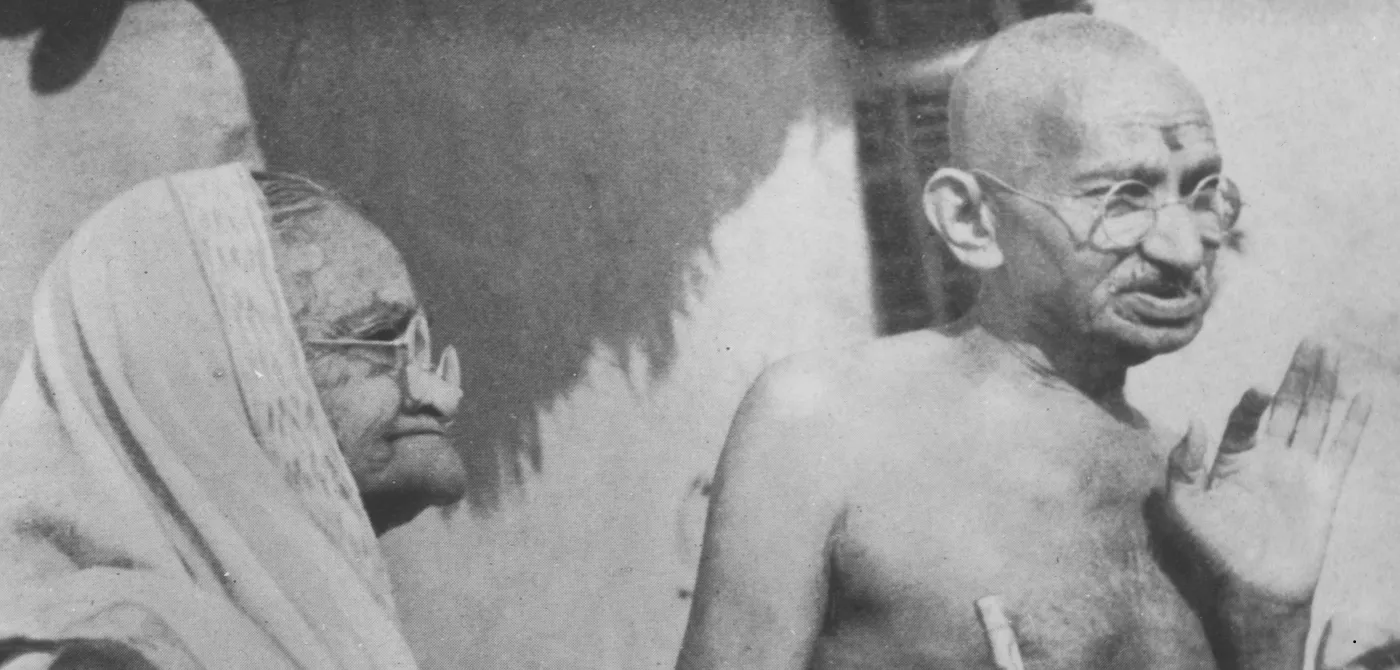

While the former reveals the intense personal and political friendship between Gandhi and Sarla Devi Chaudhurani through a study of their correspondence in an early period of Gandhi’s political career in the 1920s, the latter explores the complicated relationship between Gandhi and his grand-niece from her perspective during the tumultuous years between 1943 and 1948. It was during the latter part of this period that Gandhi, struggling to make sense of and mitigate the violence in Bengal, lay down naked with her to test his vow of celibacy, despite the reservations of many in his inner circle. For Manu Gandhi herself, Gandhi was a mother figure, an asexual being.

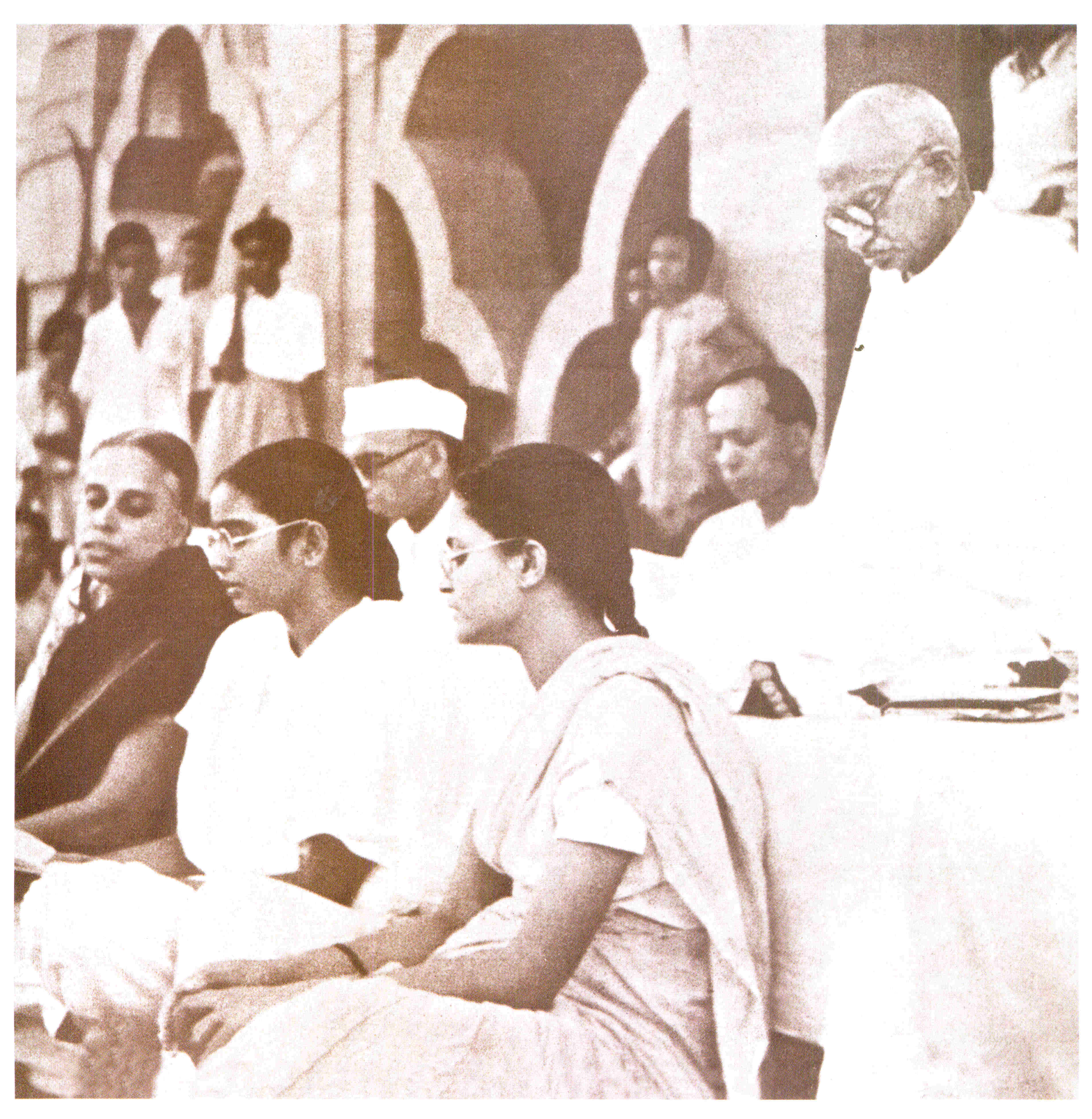

Many of the students chose to explore these relationships further and wrote about Gandhi’s evolving ideas on women, due in large part to his engagement with a variety of women from across social strata and different parts of the world through the course of his life. This also allowed them to engage with issues of women’s labour and political participation in early 20th-century India. These explorations revealed that the women in his life, including his wife Kasturba, were hardly silent victims at the receiving end of Gandhi’s strange experiments. They questioned, contested, acquiesced to, and ultimately shaped and reshaped Gandhi’s views on women, their social and political roles, and the definition of politics itself.

Others were drawn to Gandhi’s ideas on sexuality, his questioning of strictly defined gender roles, with relationships between the sexes being based on friendship and a commitment to service rather than sexuality. They discovered that even as he celebrated women as wives and mothers, he urged them not to get married and have children so that they could devote themselves to political service. Still others wrote about his ideas on diet, which resonate deeply with contemporary environmental and other concerns.

As we dug deeper, the students became troubled by Gandhi’s contradictory ideas on caste, his willingness to fight against untouchability while at the same time denying the possibility of political representation for Dalits, and some chose to focus on the Gandhi-Ambedkar debate in the 1930s. As they shared their research, it became apparent that Gandhi’s ideas on women’s roles, sexuality, food, caste, and so on, were deeply intertwined. And that he could be critiqued, not for being hidebound or retrogressive, but for insisting on individual and collective moral responsibility in addressing social and political problems without adequately addressing the structural issues underlying them.

I did not expect my students to take up cudgels on Gandhi’s behalf by the end of the semester or beyond. I simply wished them to be inspired by his fearlessness in the face of injustice, and not so easily dismiss him as a “crazy pervert”…

The most productive and refreshing aspect of teaching and learning about Gandhi, for both my students and I, was not so much the greatness of his ideas, but rather his capacity to change them without compromising his essential principles; to admit that he was wrong and embrace his mistakes. Related to this was Gandhi’s relentless drive to experiment, even at the risk of failure and opprobrium because he undertook these experiments publicly. All this made us deeply uncomfortable, not least because we live in a world of moral certainties—our own most of all—and stories of towering success. This leaves us instantly suspicious of people who change their minds and downright contemptuous of those who slip up in any way. But perhaps now we could try to put ourselves out there more, even though we might be disappointed with the results.

For me, as a biographer of another controversial figure from the subcontinent whose legacy has seen its vicissitudes and is contested in the present by the younger generation, the course raised the important issue of our responsibility as historians and educators in mediating the past in a fast-paced, atomised information age. How do we create knowledge about historical figures whose ideas are ostensibly not in step with the times? Rather than dismissing the concerns of the social media generation about these individuals, or offering apologia for their actions and ideas, incorporating the apprehensions into our teaching and writing can yield fruitful dividends. An emphasis on the mutability of these individuals’ ideas as they navigated complex local and global environments through the course of their lives and public careers renders them more human as well as more meaningful in the present.

I did not expect my students to take up cudgels on Gandhi’s behalf by the end of the semester or beyond. I simply wished them to be inspired by his fearlessness in the face of injustice, and not so easily dismiss him as a “crazy pervert”, and perhaps also not allow others among their cohort to do so. I hope that the seminar succeeded in that regard, if only in some small measure.

This essay is dedicated to the students of the Fall 2024 “Gandhi in the World” seminar at William & Mary, and our collective learning experience.

Chitralekha Zutshi teaches history at William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, and is the author of Sheikh Abdullah: The Caged Lion of Kashmir (HarperCollins Publishers India and Yale University Press, 2024).