Farmers have been protesting at the Delhi borders against the central government’s three farm laws for six months now. They have braved police action, arrests, concrete barriers, iron spikes, suspension of water, electricity and internet, relentless vagaries of weather, and even the deaths of comrades and kin. Yet, they remain firm in their protest. What makes them stay on? Who inspires them? The protest art in Ghazipur, Tikri, and Singhu borders may offer some insight.

At each of these sites, the atmosphere is thick with sounds of protests. Walking through the camps set up by the farmers, one encounters people making speeches and chanting slogans, singing songs of protests or enacting plays. Songs released by Punjabi and Haryanvi singers in support of the farmers circulate on social media and fill the air at the protest camps: Ailaan (Declaration) by Kanwan Grewal, Zaalam Sarkaran (Oppressive governments) by Gippy Grewal, Kissan vs Dilli (Farmer vs Delhi) by Ajay Hooda, Bagawataan (Rebellion) by Jazzy B, Kisaan Anthem (Farmers’ Anthem) by a group of singers, to name a few.

Standing up to Dilli

Most music videos include actual photographs and videos from the protest movement: we see large groups of protesting farmers, men, women and children their hands raised in protest, caravans of tractors on their way to Delhi. Protestors are showing living in trolleys and tents on the road, making food, holding meetings, marching and organizing langar and medical camps. The images of police brutality are interspersed with shots of protestors feeding the police.

Why should the city of Delhi be spoken at with such defiance? What do the protesters mean when they raise the slogan of Dilli Fateh?

At the protest sites, the trolleys, tractors, tents of the farmers are covered with handwritten and printed posters, banners, paintings, stickers and flags. They carry portraits of leaders of peasant struggles, martyrs who fearlessly gave up their life as they defied oppression, revolutionaries who challenged British rule, Dalit leaders and anti-caste reformers, and heroes of 1857. Portraits of tribal leader Birsa Munda appear with those of Ambedkar, Bhagat Singh and Savitribai Phule. The poetry of Nanak coexists with the words of Lal Singh Dil, and Sant Ram Udasi. There is Shahmal Jat, with Banda Bahadur, Bhagat Singh, and Ajit Singh. The same portraits also appear in the music videos. These historical figures are powerful icons of protest dotting the landscape of the farmers’ movement on Delhi borders.

One of the most resonating sentiments to emerge from the popular protest art of this movement is of Dilli Fateh, victory over Delhi. A sticker on a tractor at Tikri warns: “Punjab Nal Pange Nahio Change!” (It is foolish to mess with Punjab!). A handwritten poster hanging inside a tent at Tikri makes clear the intent of the protestors “Dilliye Jit ke Jawange” (O Delhi, We shall triumph!). A printed banner, attached to a tanker at Singhu, shows the Sikh hero Banda Bahadur and announces “Dilli Fateh” (Delhi is Conquered). The posters, slogans and music videos all convey the same message – support for the farmers’ movement as a just fight, and an audacious defiance of and triumph over Delhi.

Why should the city of Delhi be spoken at with such defiance? What do the protesters mean when they raise the slogan of Dilli Fateh? Why should they wish to conquer Delhi? And what is the value of this idea for the farmers’ protests?

Claiming the centre

The idea of ‘conquering’ Delhi has long been part of the popular imagination and political expression in Punjab, particularly in the Sikh community. Delhi represents the seat of power and the call for its conquest is primarily about subduing the arrogance of those in power. It is about reminding them to be just and to work for the masses over whom they rule.

There is a strong perception in Punjab that through the centuries the region has suffered at the hands of rulers who are arbitrary and tyrannical. And that, time and again, Punjab has produced saints, martyrs and revolutionaries who have defied such authorities in their fight for justice and freedom. Their stories are deeply embedded in the popular cultural imagination in Punjab. There are sakhis, popular life accounts, of Guru Nanak speaking up against the devastation caused by the military campaigns of the Mughal ruler Babur. Another story is of Guru Teg Bahadur’s opposition to Aurangzeb’s bigotry and his willingness to embrace martyrdom in Delhi in defence of his beliefs. The sacrifice of the Chhote Sahibzade, the younger sons of the last Sikh guru Gobind Singh, aged seven and nine years, respectively, who fearlessly withstood Mughal intimidation and did not give up their faith is remembered each year in Punjab at the Shaheedi Jor Mela. Banda Bahadur’s spectacular military campaigns in Sirhind, known as the Sirhind Fateh, and his land reforms that practically uprooted the Mughal administration in that region of Punjab, are spoken of with great pride. The Sikh gurus and heroes are not just religious figures particular to the Sikh community. They are remembered by all Punjabis as people who spoke for the most marginalised sections of society, and stood up against oppressive rulers even at the cost of their lives.

The idea of subduing Delhi’s arrogance has been a powerful motivator in Punjab politics.

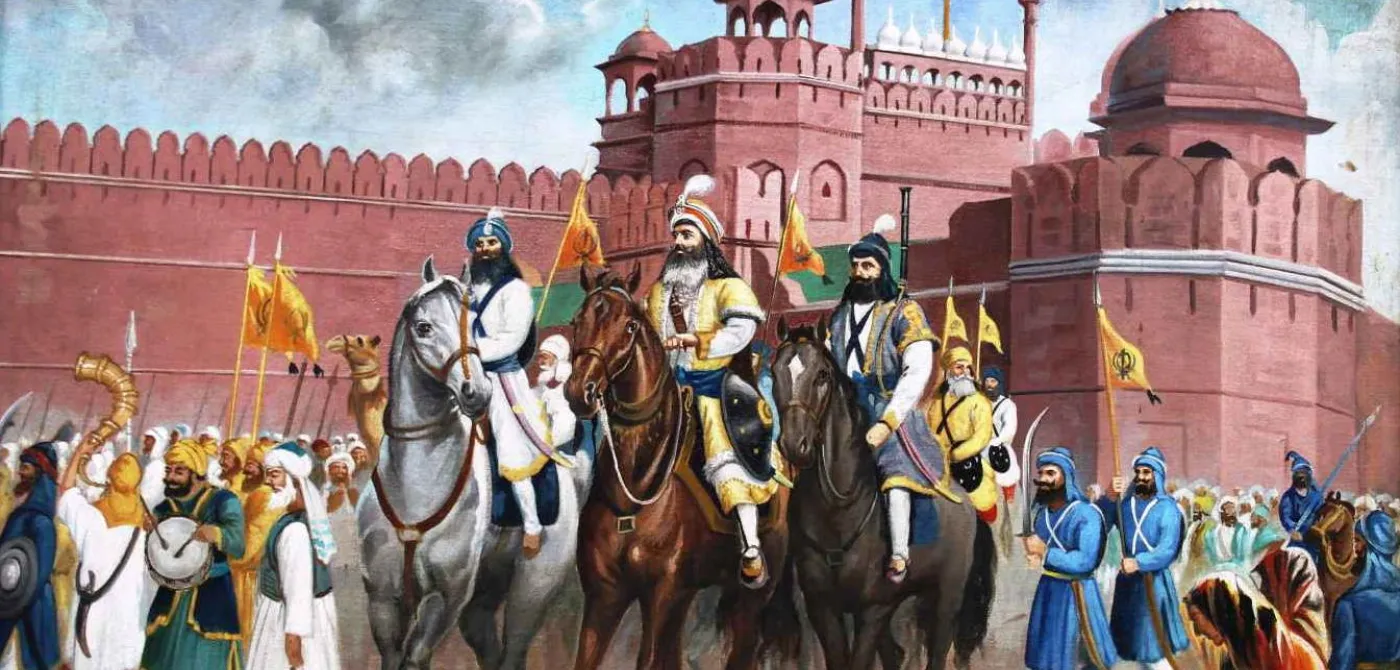

Perhaps the most popularly invoked figure in terms of ‘conquering’ Delhi is Baghel Singh, a Sikh military commander from the 18th century. As the story goes, the Sikh army led by Baghel Singh, Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, and Jassa Singh Ramgarhia, conquered Delhi in the year 1783. They defeated the Mughals, sat on the emperor’s throne and raised the kesari Nishan Sahib on the Red Fort. They led a victory procession through the streets of Delhi that was joined by Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs as they welcomed the Sikh forces for liberating them from Mughal tyranny. The Sikhs established their domination over Delhi, and Begum Samru and the Mughal emperor, Shah Alam, had to plead to them to spare the throne. The Sikh chiefs were not interested in actually ruling over Delhi and only wanted to teach the Mughals a lesson. It is said that they agreed to give up Delhi in exchange for the right to build gurdwaras in the city. This is a powerful story celebrating the Sikhs’ history of fighting for justice against oppressive rulers and their magnanimity even towards their opponents. Popular paintings depicting this story are widely recognized and used in the popular visual culture in Punjab, including in museums, calendars, popular tracts, and at the farmers’ protests.

In independent India too, the central governments at Delhi are seen as depriving Punjab of its resources and following a sectarian and discriminatory attitude towards the Sikhs. ‘Hindu-dominated’ central governments, led by the Indian National Congress for the longest time since Independence, are seen as working against the interests of the Sikh community. This remained a prominent sentiment in many Sikh political movements in Punjab and is perceived to be a continuation of the historical oppression suffered by the community since its inception. Hence, the idea of subduing Delhi’s arrogance has been a powerful motivator in Punjab politics.

The past in the present

The protest art of the farmers’ movement is vividly coloured by the deep-rooted cultural memory of Delhi’s injustice and the ability of the Punjabis to fight against it. At the farmers’ protests, the call for Dilli Fateh is a challenge to the BJP-led central government in Delhi against the provisions of the farm laws, the arbitrary nature of their implementation and the repressive measures taken by the government.

A sticker on a tractor at Tikri shows a plough, representing the farmers, uprooting Parliament; and declares that it is unwise to mess with Punjab. It symbolises the collective strength of the farmers dislodging the rulers who have misused their power in Parliament. Along with this image, there are two more stickers proclaiming “I love Kheti” [farming] and “Proud Farmer”; indicating the protestors’ confidence in their stance. A banner at Singhu with the image of Banda Bahadur states matter of factly: Dilli Fateh: koi kise ko raj na de hai, jo le hai nij bal se le hai [Dilli Fateh: No one offers sovereignty to anyone. Whoever achieves it, is through their own strength]. It portrays Banda in a confident and gutsy stance, ready to face any challenge.

Each line of the tremendously popular Ailaan, throws a challenge to Delhi:

“Bas chaar panj ghantiyan di vat dilliye Tainu yaad karwa denge aukat dilliye Teri hik utte chadh ke jaikare launge Saadi hausla afzai aasman karuga … Asi haq di ladai haq nal ladenge … Tainu dilliye ikkath pareshan karuga Par faslan de faisle kisan karuga” You are just 4-5 hours away, O Delhi We will remind you of your status, O Delhi We shall raise the slogans of victory on your chest The sky above lends us courage … We shall fight for our rights in a just way … We shall gather, O Delhi, to unsettle you Farmers alone will make decisions on farming

The video accompanying Ailaan opens with the images of a Nihang Sikh beating a large drum as if announcing the beginning of a war. As the lyrics unfold, we see images of children and men (including Grewal) in a rural landscape, standing in defiance, staring into the camera with determination. They hold green and white flags of the farmers’ unions and placards registering their protest against the farm laws and proclaiming the solidarity of farmers and workers. The song declares that this is a just battle being fought by the farmers for their right to own and make decisions about their land and their produce. It warns the powers residing in Delhi that they should beware of the collective strength of the farmers that shall destroy the arrogance of the policy makers.

The historical continuity between the past and the present are made even more clear in music videos such as Bagawatan, where visuals of the protesting famers are interspersed with images of Baghel Singh’s conquest of Delhi. The throbbing beats of the drum, the visuals of the simple yet steadfast determination of the protestors, the defiant words of the songs and slogans, and the historical memory of triumph over Delhi make for an intensely emotional and inspiring experience for the protestors.

These cultural expressions of the protests announce the resolve and tenacity of the people of Punjab, their ability to fight against all odds and of subduing the arrogance of those in power. The call of Dilli Fateh is a reminder to the rulers sitting in Delhi.