The last ten years have seen a quiet but major change in India’s healthcare system: the rapid growth of state-sponsored health insurance. Ten years ago, only a few of India’s 20 major states (mainly in the southern and western regions) had a broad health insurance scheme for the general population. Today, all of them have one, with the partial exception of Bihar. 1Major states are defined here as those with a population of more than 5 million in 2011. This excludes the north-eastern states other than Assam. In 2011, these 20 major states accounted for 96% of India’s population. Bihar appears to be in the process of launching a state health insurance scheme (the Mukhyamantri Jan Arogya Yojana), but little information on this scheme is available at the time of writing.

In addition, India has a national health insurance scheme under Ayushman Bharat, the Pradhan Mantri Jan Aarogya Yojana (PMJAY). In 2023-24, this scheme covered 58.8 crore individuals with a budget of about Rs 12,000 crore: Rs 7,200 crore from the central government, and another Rs 4,800 crore or so from state governments (assuming that they contribute 40% of the total, as prescribed by the scheme guidelines). Taken together, however, the health insurance schemes of the major states are larger: in the same year, they covered a similar proportion of the population and had a combined budget of at least Rs

The table in the Appendix may not be free of inaccuracies, for three reasons. First, it is not always easy to extract comparable data from state-specific portals. Second, some SHIPs are undergoing rapid change over time. Third, in some states it is difficult to “separate” the state scheme from PMJAY. We mention these qualifications for the benefit of potential users of the table – they are of little consequence for the broad patterns discussed in this article.

PMJAY versus SHIPs

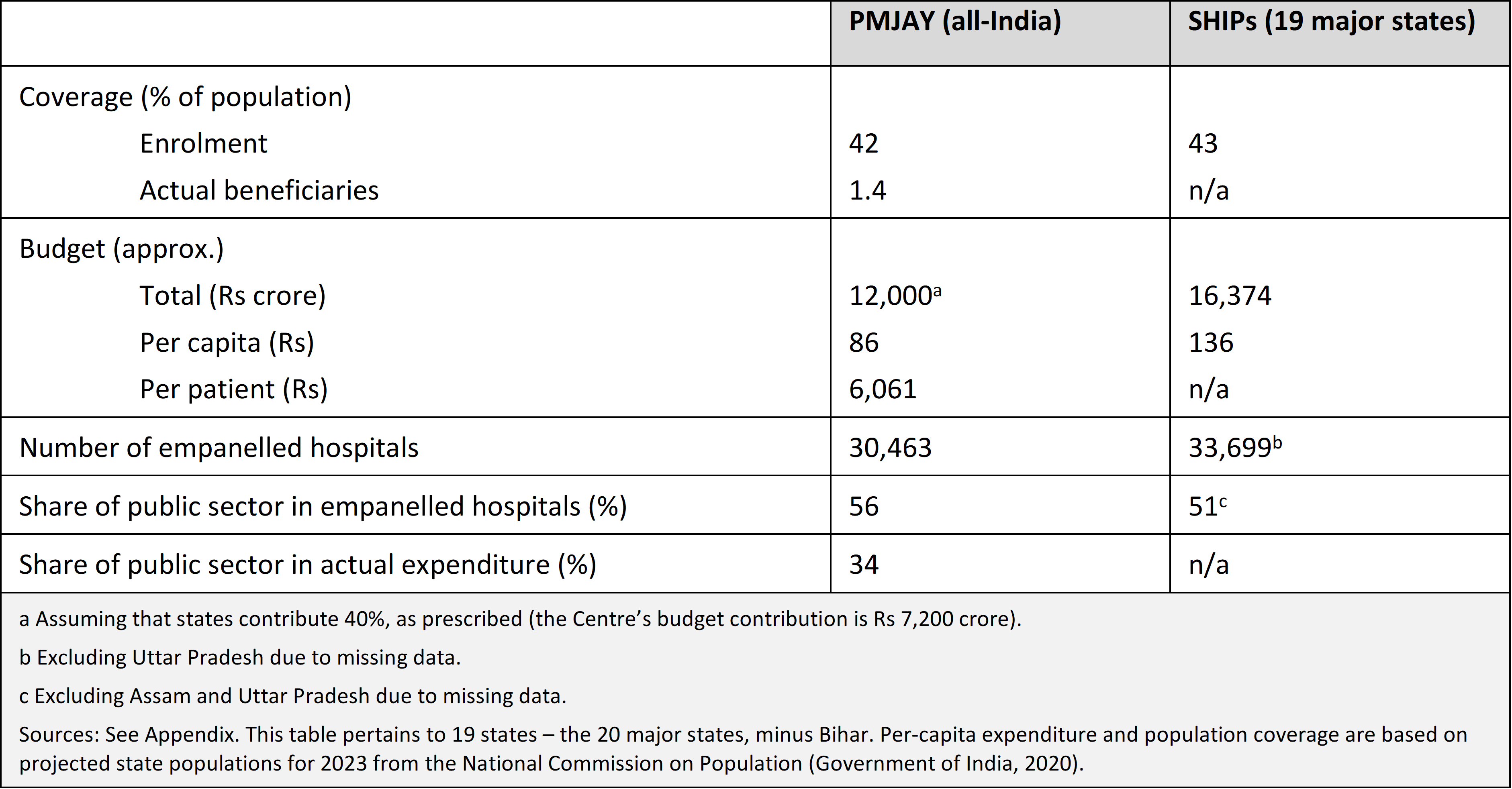

Most of the SHIPs are designed in a similar way, not very different from PMJAY. Our main focus here is on significant variations between SHIPs, e.g. in terms of eligibility conditions and the public-private mix of empanelled hospitals. Before looking at these contrasts, a broad comparison between PMJAY and the SHIPs may be helpful. For this purpose, we “aggregate” the SHIPs across all major states (except Bihar), and then compare all-SHIPs indicators with the corresponding PMJAY figures for India as a whole – see Table 1. Here and elsewhere, the reference year is 2023-24 unless stated otherwise.

The centre’s propensity for centralization is balanced by an increasing involvement of states with social programmes. Centralization seems inappropriate in this field, since healthcare is a state subject.

Taken together, the SHIPs appear to be similar to PMJAY in terms of coverage (a little over 40% of the population in both cases), number of empanelled hospitals (around 30,000), and share of the public sector in empanelled hospitals (a little more than half). Other indicators are not easy to compare, due to a lack of transparency in some of the SHIPs. For instance, the number of actual beneficiaries of these programmes is not always clear. Similarly, as the last row of Table 1 below indicates, it is not clear how SHIP expenditure is divided between public health facilities and the private sector. In the case of PMJAY, about two thirds of the money goes to private hospitals – an alarming sign that health insurance is nudging patients towards the private sector, in a system where commercial healthcare is bloated in the first place. Quite likely, SHIPs are doing the same, but it is hard to tell from available data. In this and other respects, SHIPs are begging for higher levels of transparency.

Table 1: PMJAY versus SHIPs, 2023-24

Similarities and contrasts

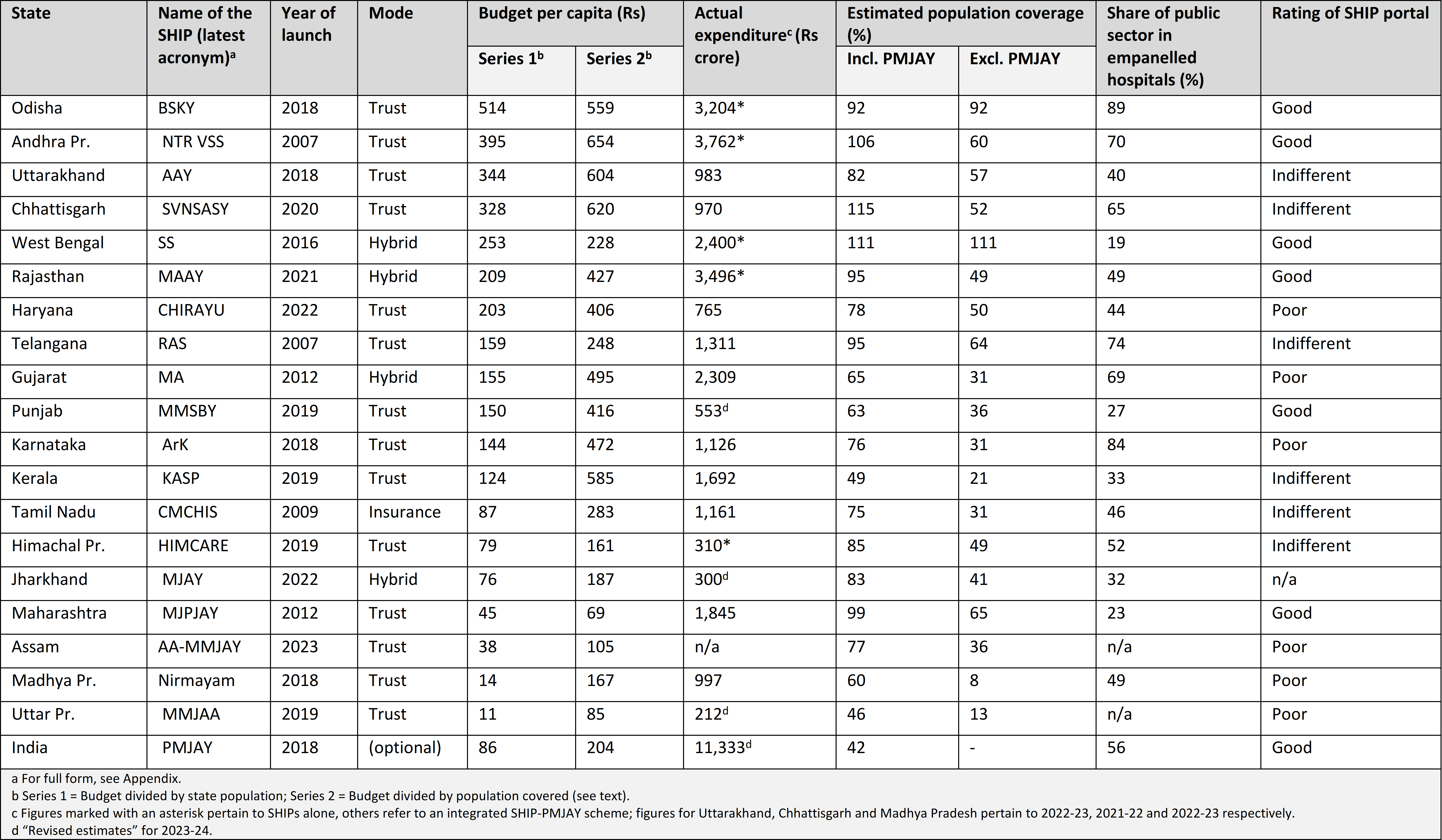

Summary indicators for SHIPs of the same 19 major states, extracted from the Appendix, are presented in Table 2. In this table, states are ranked in descending order of the SHIP budget in per-capita terms (i.e. divided by state population). 3Here and elsewhere, we use population projections for 2023 from the National Commission on Population (Government of India, 2020). The range is very wide: from just Rs 11 per person in Uttar Pradesh to Rs 514 per person in Odisha. These and other contrasts are discussed in more detail below.

Chronology

Most of the SHIPs are recent initiatives, launched in or after 2018, when PMJAY was introduced. The southern states, however, made an early start: all of them launched SHIPs between 2007 and 2010

About half of the SHIPs, and more than half of the recent ones, are named after the state’s chief minister. The growing tendency of the centre and states to name welfare schemes after the prime minister and chief minister (respectively) is a symptom of the tussle for ownership of these schemes. The centre’s propensity for centralisation is balanced by an increasing involvement of states with social programmes. Centralisation seems inappropriate in this field, since healthcare is a state subject.

Mode of implementation

Under India’s Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY), the precursor of PMJAY, the main role of the state was to identify the beneficiaries and then pay the insurance premium to insurance companies (public and private) on their behalf. Implementation was largely in the hands of insurance companies. This can be problematic since insurance companies have an incentive to maximise enrolment and minimise claims (or their settlement).

PMJAY departed from this approach in favour of allowing each state to choose between three options: the 'insurance mode', 'trust mode', and 'hybrid mode'. In the RSBY-like insurance mode, the main implementation agency is an insurance company (a public-sector company in most cases, one notable exception being Bajaj Allianz in Gujarat). In the trust mode, the scheme is implemented by a State Health Agency (SHA), with the SHA directly reimbursing healthcare providers. The hybrid mode is based on a partnership between the SHA and the insurance company or companies.

In 2023-24, all the SHIPs operated in trust mode, except four (Gujarat, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, West Bengal) that worked in hybrid mode and one (Tamil Nadu) that appears to have opted for the insurance mode.

Maximum cover

Most of the SHIPs (15 out of 19) have a maximum cover of Rs 5 lakh per household per year, like PMJAY. Some states, however, have higher limits, e.g. Rs 10 lakh in Gujarat and Telangana and Rs 25 lakh in Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan. In Odisha, the maximum cover rises from Rs 5 lakh to Rs 10 lakh for female members of the registered households. In some states, the maximum cover varies for different groups, with Rs 5 lakh per household per year as a general norm.

Eligibility and coverage

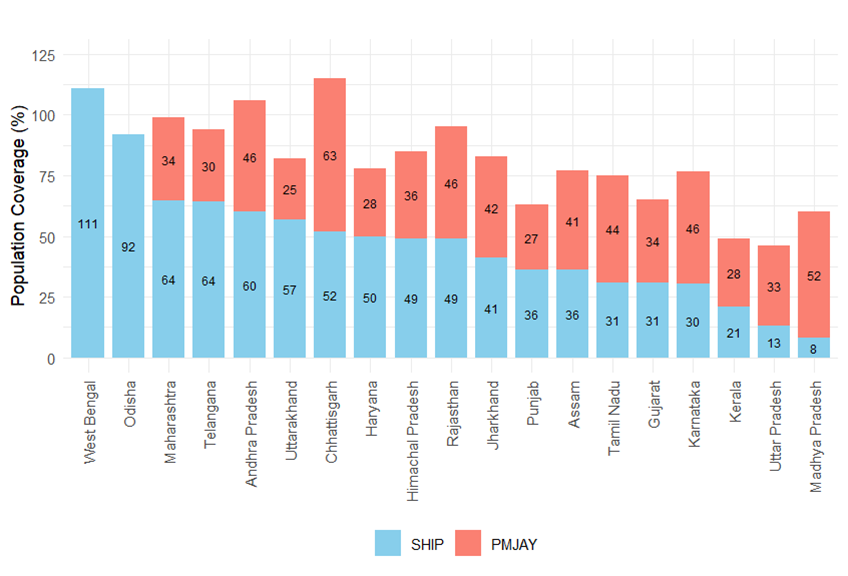

Figure 1 presents state-specific estimates of PMJAY and SHIP coverage, defined as the proportion of the population registered under the relevant scheme. In most states (except Kerala and Uttar Pradesh), a large majority of the population is covered. However, there are wide variations in the respective shares of PMJAY and the local SHIP. By and large, states with high overall coverage are also states where the local SHIP has much wider coverage than PMJAY. Seven states have overall coverage above 90% according to these estimates: Odisha, Telangana, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and West Bengal. In the last three, the number of beneficiaries in 2023-24 was higher than the National Commission on Population’s projected state population for that year.

Figure 1: Estimated Population Coverage: SHIPs and PMJAY, 2023-24

Odisha and West Bengal are two cases of special interest. Both have skipped PMJAY and launched their own SHIP (Biju Swasthya Kalyan Yojana and Swasthya Sathi, respectively), more or less universal in both cases. 5The West Bengal government initially participated in PMJAY but later withdrew from it. The Odisha government has plans to implement PMJAY from 2025, in convergence with the state scheme (recently renamed Gopabandhu Jan Arogya Yojana). Odisha’s SHIP covers 92% of the population and also stands out for a very high share of public facilities among empanelled hospitals, partly due to large-scale empanelment of Community Health Centres (CHCs) and Primary Health Centres (PHCs). Odisha is a rare example of an Indian state that has been quite active in the field of healthcare in recent years and where healthcare is also a lively electoral issue (Reddy, 2024). According to the National Health Accounts, the share of out-of-pocket expenditure in total health expenditure declined from 72% to 37% between 2015-16 and 2021-22 in Odisha (Rout, 2024).

By and large, states with high overall coverage are also states where the local SHIP has much wider coverage than PMJAY.

Regarding eligibility criteria, most states seem to be using inclusion criteria rather than exclusion criteria. Common inclusion criteria are possession of a ration card, BPL status, low income, and various occupations. In some states, the SHIP also covers vulnerable categories of individuals such as migrant workers and transgender persons, and possibly their families as well (e.g. construction workers and their families in Maharashtra). PMJAY beneficiaries are normally excluded from the SHIP, unless PMJAY itself has been subsumed under it. (PMJAY eligibility is based on deprivation and occupational criteria derived from the Socio-Economic and Caste Census 2011.)

In some states, there is universal eligibility in the sense that households left out by inclusion criteria can still join the SHIP if they wish by paying a premium. Rajasthan is an important example. In Odisha, all residents are entitled to free healthcare in public hospitals under the Biju Swasthya Kalyan Yojana, and vulnerable groups (70 lakh households or about two thirds of the state population) are also entitled to free healthcare in empanelled private hospitals. In West Bengal and Maharashtra, all permanent residents seem to be eligible for the SHIP (Swasthya Sathi and Mahatma Jyotirao Phule Jan Arogya Yojana, respectively), free of cost.

It is worth noting that the coverage of health insurance based on official figures is considerably higher than coverage estimates based on household data. According to the fifth National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), only 41% of Indian households in 2019-21 had at least one member covered by health insurance. This contrasts with a population coverage of more than 80% in 2023-24 for PMJAY and SHIPs combined (see Table 1). It is possible that the NFHS-5 figures are on the low side: oddly, they make no room for PMJAY. 6The reason seems to be that the NFHS-5 questionnaires were printed in December 2017, before PMJAY was launched. PMJAY, it appears, ended up being clubbed with “other” health insurance schemes (e.g. in Table 11.13 of the NFHS-5 report). Also, there was a major expansion of SHIP coverage in several states between 2019-21 and 2023-24, helping to reconcile NFHS-5 figures with official data. Nevertheless, it is possible that official figures give an exaggerated impression of the actual coverage of health insurance. Some households, for instance, may be nominally registered in a health insurance scheme without knowing much about it or how to utilize it.

Range of procedures

Like PMJAY, all SHIPS focus almost exclusively on in-patient care. However, there are one or two interesting exceptions. For instance, Andhra Pradesh’s SHIP includes a monthly allowance of Rs 5,000 for post-surgery recovery, to compensate for the possible loss of earnings. Some states (e.g. Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh and West Bengal) have a provision for transport allowances in the event of hospitalization.

Within in-patient care, all SHIPs cover a large number of medical procedures (also called 'packages', though packages can also include multiple procedures) – from 1,356 procedures in Maharashtra to more than 3,000 in Andhra Pradesh and Himachal Pradesh, compared with 1,949 under PMJAY. Most states, however, disclose little information about the distribution of SHIP expenditure over different procedures. 7Some information on this is available for PMJAY; see e.g. Accountability Initiative (2023), pp. 5-6. The shares of different procedure categories (e.g. oncology, cardiology, general surgery) vary widely between different states, for no obvious reason.

Budget and expenditure

To compare SHIP budgets across states, it is useful to put them on a per-capita basis. We can do this in two ways: divide the SHIP budget by the state population, or divide it by the population covered (i.e. the number of registered beneficiaries). The first ratio is equal to the second multiplied by the coverage rate. Both are presented in Table 2.

Table 2: SHIPs Overview, 2023-24

Wide inter-state variations emerge not only in the first series (as noted earlier), but also in the second. This may seem a little surprising, considering that SHIP entitlements are similar across states. Budget per registered beneficiary ranges from just Rs 69 per year in Maharashtra to

Actual SHIP expenditure tends to exceed the SHIP budget, often by a large margin. This points to an important feature of SHIPs: they have a tendency to balloon.

We also tried to estimate actual SHIP expenditure, but in many states it is difficult to separate SHIP expenditure from the state’s share of PMJAY expenditure. For convenience, let “SHIP+” expenditure refer to the sum of the two. The tentative expenditure estimates presented in Table 2 pertain to SHIP+ in most cases, and to SHIP expenditure alone in some cases (as indicated). Estimates of actual SHIP+ expenditure are much higher than SHIP budgets, and in most cases the gap between the two is too large to be explained by the PMJAY component. 8This comparison is based on figures presented in the Appendix. In other words, actual SHIP expenditure tends to exceed the SHIP budget, often by a large margin. This points to an important feature of SHIPs: they have a tendency to balloon.

The same pattern can be seen in expenditure trends over time. For a few states, we were able to estimate the annual growth rate of SHIP+ expenditure from 2018-19 to 2023-24. The results are: 13% per year for Maharashtra, 19% for Gujarat and 30% for Kerala. These are nominal growth rates, but even after deducting 5% or so for inflation, the growth rates would range between 8% and 25% in real terms. One exception to this pattern of runaway expenditure growth is Tamil Nadu, where SHIP+ expenditure did not increase (even in nominal terms) between 2018-19 and 2023-24. This shows the possibility of containing SHIP expenditure, but the general pattern seems to be one of very rapid growth in recent years. As India’s population ages in the near future, SHIP expenditure is likely to keep growing fast, unless a serious effort is made to expand out-patient care, preventive care and public health.

Public-private mix

One important contrast between SHIPs relates to the share of the public sector in empanelled hospitals and programme expenditure. When SHIP money is spent within the public sector, it can be a useful source of additional funds for active hospitals and health centres. Some district hospitals, for instance, have made good use of health-insurance money to improve their facilities. SHIP funds, however, are also spent on the private sector. This contributes to further privatisation of a highly privatised healthcare system. In the standard health-insurance framework, it is the patient who chooses between public and private health centres. But one can make a case for tilting the pitch in favour of public health centres, on the grounds that insured patients tend to overestimate the quality of private healthcare and disregard its inflated costs.

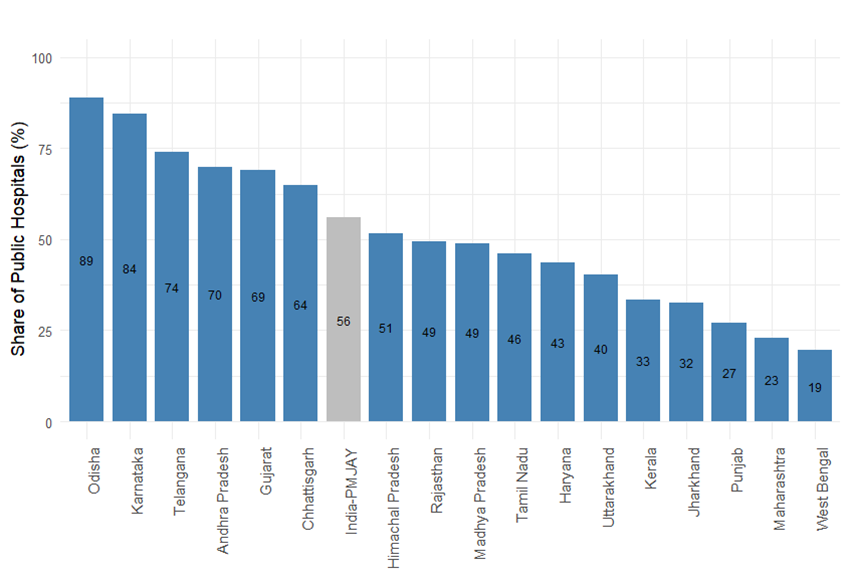

For all SHIPs together, the share of the public sector in empanelled hospitals is around 51% – not very different from the PMJAY figure of 56% (Table 1). Within the public sector, SHIPs tend to promote district hospitals and other large hospitals. However, they often cover Community Health Centres (CHCs) as well, and even Primary Health Centres (PHCs) in some states, e.g. Chhattisgarh and Odisha. This downward extension seems important to ensure that SHIPs help to strengthen the base and not just the top of the healthcare pyramid.

Figure 2: Share of Public Facilities in Empanelled Hospitals

As Figure 2 indicates, the public sector share of empanelled hospitals varies widely across states, from just 19% in West Bengal and 23% in Maharashtra to 84% in Karnataka and a startling 89% in Odisha. 9Figures for Assam and Uttar Pradesh are not available. Quite likely, the high ratios in states like Karnataka and Odisha reflect the empanelment of PHCs in addition to CHCs. What is not clear is whether they also reflect a policy of deliberate promotion of the public sector, as opposed to letting health insurance drift towards the private sector.

Further scrutiny of the public-private mix would require data on the distribution of SHIP expenditure between public and private health facilities. As mentioned earlier, for PMJAY the expenditure share of the public sector is barely one third. Corresponding figures for SHIPS, unfortunately, are not available in most cases. Here again, there is an urgent need for greater transparency.

Scheme portals

This study was an opportunity to familiarise ourselves with the SHIP portals. These portals, aside from disclosing information of public interest, are supposed to help SHIP users, e.g. by providing them with details of empanelled hospitals and treatments covered. We found many of them seriously deficient, e.g. in terms of scope and user friendliness (informal ratings are presented in Table 2, last column). In Jharkhand, the SHIP does not seem to have its own portal at all. Haryana’s SHIP portal was not functional at the time of writing. In many states (e.g. Assam, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh), the SHIP portal provides very limited information. Some SHIP portals are more informative, but not particularly user-friendly (e.g. Karnataka, Tamil Nadu). Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Rajasthan and West Bengal have comparatively informative and user-friendly portals. Odisha has a particularly useful interactive dashboard.

One gaping hole in all SHIP portals is the lack of information on audit reports. Without strict auditing, health insurance schemes are very vulnerable to abuse. SHIPs do have auditing systems, in principle at least, but we were unable to find any trace of audit reports on their portals.

Transparency (subject to privacy norms) is absolutely critical in health insurance schemes, partly because they are prone to corruption, and partly because many patients find the system difficult to navigate. All SHIPs can do better in this regard, and many have a long way to go.

Where are SHIPs going?

In matters of health insurance, it is important to distinguish between commercial insurance and social insurance. Commercial insurance is driven by profit-seeking. Social insurance is geared to the public interest.

Canada and the United States present a useful illustration of this contrast. In the US, health insurance is a business. Healthcare itself, quite often, is also a business. The result, for reasons that are relatively well understood in economics, is one of the most expensive, inefficient and inequitable healthcare systems in the world. The worst aspect of the system is that a significant minority of the population is bereft of health insurance. In a country where healthcare is very expensive, this is a disaster.

In Canada, health insurance is compulsory, universal, and largely financed from general taxation. Healthcare is free at the point of use. There are private as well as public healthcare providers, but private hospitals are mainly non-profit. All healthcare providers come under the health-insurance umbrella. This is a highly egalitarian, effective and popular healthcare system.

In between these two extremes, there is a whole spectrum. Many countries (e.g. Germany and Japan) have a social insurance system that makes room for private health insurance agencies, but mainly non-profit agencies. Similarly, social insurance tends to restrict for-profit healthcare provision, and to regulate it tightly where it is allowed. Among developing countries, Thailand is an important example of a relatively successful system that combines social insurance with extensive public provision of healthcare.

When India’s RSBY was launched, the project was greeted with euphoria by private insurance agencies, since RSBY essentially subsidised them. PMJAY may be regarded as a limited move in the direction of social insurance, compared with RSBY. For-profit insurance companies have been largely sidelined. Yet, PMJAY still lacks many features of social insurance. It is not universal, and it gives ample space for poorly-regulated, for-profit healthcare providers. The same applies to most SHIPs.

No doubt, PMJAY and SHIPs provide some relief to poor patients when they need hospital treatment and public facilities are overcrowded or substandard. However, these schemes also carry three major dangers. First, they tilt the healthcare system towards hospitalisation and tertiary care, when investments in primary care may be more urgent. Second, they promote private healthcare (by subsidising it), in a country where for-profit healthcare is already bloated. Third, health insurance schemes are highly vulnerable to corruption and abuse. This danger is magnified by India’s persistent failure to regulate private healthcare providers.

SHIPs may provide some relief in a situation where the public sector has limited capacity, but they should not be confused with a sound framework for healthcare.

In response to the last two, it may be argued that SHIPs present an opportunity for better regulation of the private sector, because they hold private providers accountable to minimum norms. It is far from clear, however, whether they really play that role, or, on the contrary, breed further abuses. In principle, most SHIPS (and PMJAY) include extensive provisions for guiding, monitoring and auditing private providers. In practice, it is anyone’s guess how these provisions actually work – we found very little information on this. Quite likely, there is plenty of window-dressing. Reports of corruption and fraud abound. 10See e.g. Comptroller and Auditor General of India (2023), Express News Service (2023), Pathare (2023), Times of India (2023), Upadhyay (2023), Tribune News Service (2024). In Himachal Pradesh, private hospitals were recently excluded from the HIMCARE scheme due mounting evidence of inflated claims and other irregularities.

Recent studies of PMJAY and SHIPs point to further concerns about these schemes. 11See D’Cruze (2020), Garg et al. (2020), Jain (2021), Furtado et al. (2022), Dubey et al. (2023), World Health Organization (2023), Kashyap (2024), among others. For instance, poor people are not always able to make good use of them; patients are often charged by private providers, against the rules; reimbursements of claims are often delayed; and some private providers perform unnecessary procedures to milk the scheme. Except for reimbursement delays, none of these problems “show” in the SHIPs’ alluring portals. There is an urgent need for more research on the ground realities.

Commercial healthcare always involves a tension between private profit and the public interest. This tension arises from the fact that a patient is a sitting duck. Unlike the enlightened consumer of economic textbooks, she is not well placed to know what she needs. This opens the door to profiteering and exploitation. The presumption behind SHIPs is that this tension can be resolved by insistence on strict protocols, oversight, audits, and so on. However, there is no evidence that these safeguards are effective as things stand.

In short, SHIPs may provide some relief in a situation where the public sector has limited capacity, but they should not be confused with a sound framework for healthcare. Of course, they are unlikely to go away. On the contrary, there is likely to be continuing pressure for SHIPs to expand. This makes it all the more important to understand how they work, the dangers they present, and the safeguards they call for. It also raises the question whether and how SHIPs can be taken further in the direction of social insurance rather than commercial insurance. For instance, SHIPs could perhaps be used to help public institutions such as universities to run non-profit health centres for their students and faculty. In this and other ways, they could help to promote non-profit rather than for-profit healthcare.

Whatever happens to the SHIPs, and to health insurance in general, what is clear is that India needs a radical expansion and improvement of public health services. Decades of public under-investment in healthcare are exacting a heavy price. The case for higher investment in preventive care, public health and primary health centres is particularly strong. Without that, more and more people are likely to rush to hospitals without referral and board the SHIP at high public expense. If the SHIPs, in addition, continue to promote the private sector, they are likely to reinforce the current bias of India’s healthcare sector towards for-profit medicine and tertiary care. This bias may be very hard to reverse as vested interests in this lopsided system become more entrenched.

Anfaz Abdul Vahab is an independent researcher. Jean Drèze is a visiting professor at the Department of Economics, Ranchi University.

Canadian health care is not perfect