Political representation is at the heart of the idea of representative democracy. Decision-making institutions are a reflection of the wider society, and legislative bodies need to be truly representative of the different class of citizens. It becomes even more challenging if one were to appreciate the representative claims of minority groups in an electoral system like India with single-member constituencies.

The issue of representation of Muslims in politics is not a crisis of recent origin or one solely due to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). In fact, it has prevailed ever since the birth of the Republic. The contribution of the Congress and other non-BJP parties has been no less in the invisibilisation of Muslims in electoral politics. The recent meteoric electoral rise of the BJP has only amplified this trend and coupled with the aggressively majoritarian political climate, has further aggravated the political marginalisation of Muslims.

The Context

The population of undivided India was 318 million in 1941, of which 66% were Hindus and 24% Muslims (Census of India). In 1951, the population increased to 361 million, but the percentages had changed radically, owing to Partition. After Independence, India was 84% Hindu and 10% Muslim in terms of population.

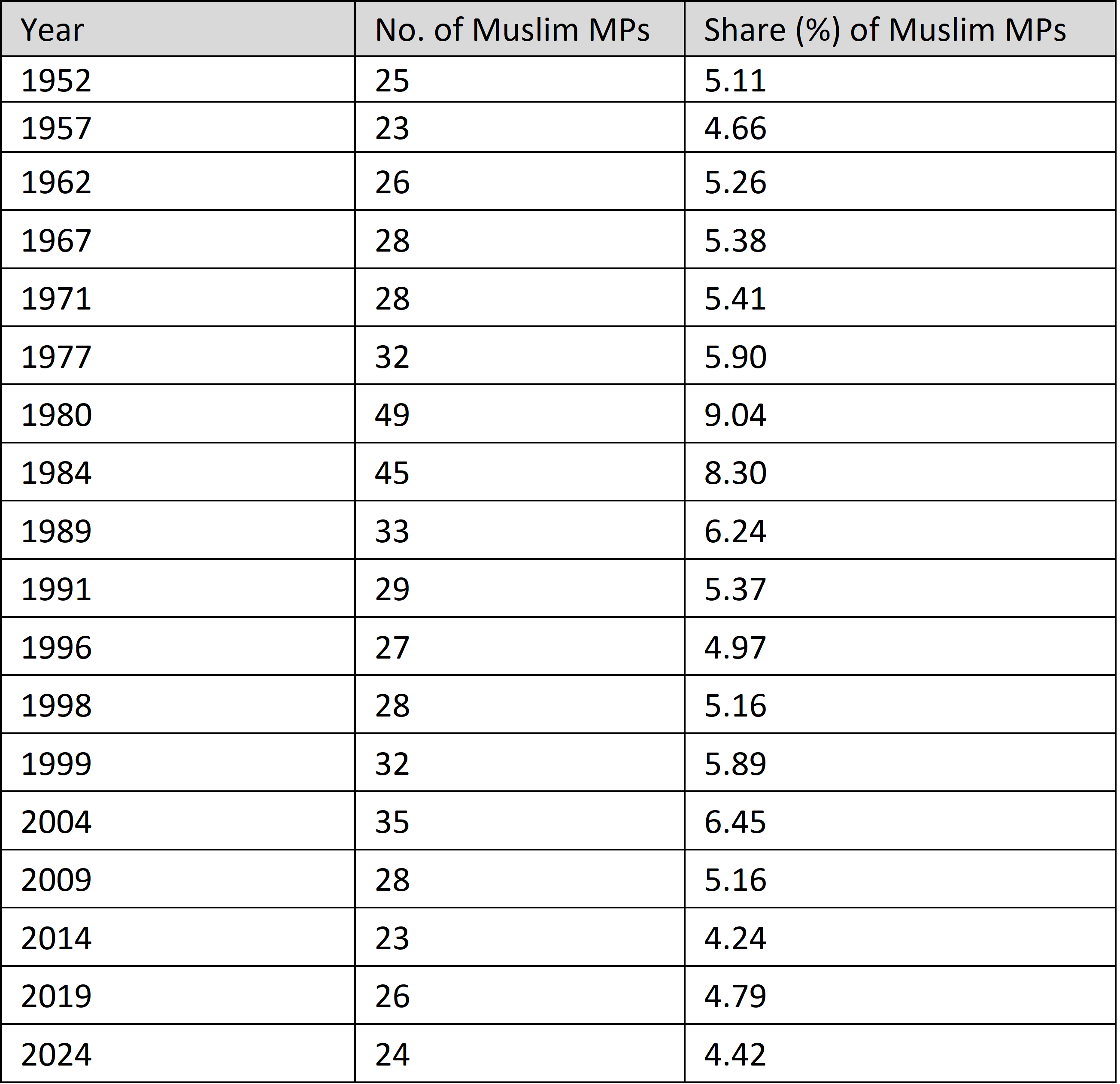

The changed equation significantly reduced the heft of Muslims in the electoral arena. Between 1952 and 1977, when Muslims accounted for about 10% of the population, only 4% of all candidates nominated by mainstream regional or national parties were Muslim. This trend did not change over the years and much fewer tickets than their proportion in the population were given to Muslim candidates by parties across the board, .

This decline becomes even more striking when contrasted with the rising Muslim population in India. In 1980, Muslim MPs comprised 9% of the Lok Sabha, while Muslims formed only 11% of the population. By 2014, despite Muslims reaching at 14% of the population, their representation in the Lok Sabha had shrunk to a mere 4%. (Unless otherwise mentioned, data on representation in this essay are from Statistical Reports of the Election Commission of India, various years).

BJP, yes; but Opposition too

The drift has been particularly notable since the electoral rise of the BJP. The 16th Lok Sabha (2014–2019) witnessed a drop to just 23 Muslim MPs from 30 in the 15th Lok Sabha. In 2019, only 26 out of 115 Muslim candidates fielded by various parties secured seats.

This trend has continued in the newly constituted 18th Lok Sabha (2024 onwards). Only 24 out of 545 MPs today are Muslim. Of these 21 MPs are from parties in the opposition INDIA bloc — Congress has nine Muslim MPs, followed by the Trinamool Congress with five, the Samajwadi Party with four, the Indian Union Muslim League with two, and the National Conference with one.

The BJP itself has fielded a handful of Muslims candidates in the past three general elections – none of whom were successful. 1The BJP fielded seven Muslim candidates in 2014, six in 2019, and one in 2024. The party has consistently defended its stance on Muslim representation, refuting claims of discrimination based on religion. Amit Shah, the home minister and one of the BJP’s top leaders, cited winnability as a crucial factor in the party's decision to exclude Muslims from its list of candidates. "Our ticket distribution is on the basis of winnability."

But the electoral marginalisation of Muslims is not restricted to the BJP. More pertinently, as the party has been able to shift the electoral discourse decisively to the right of the ideological spectrum, other political parties have been equally reluctant to field Muslim candidates, due to the fear of being charged with ‘minority appeasement.’ All political parties together in 2014 had nominated 320 Muslim candidates. This came down to 115 in 2019 and in 2024, to an all-time low of 94 (Statistical Reports of Election Commission of India).

The Congress in 2024 did not nominate a single Muslim candidate in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Uttarakhand, or Gujarat. Other major opposition parties – the Congress, Trinamool Congress, Samajwadi Party, Rashtriya Janata Dal, Nationalist Congress Party and the Communist Party of India (Marxist) – together gave tickets to only 43 Muslim candidates in the 2024 elections.

To argue that we need Muslims in representative bodies to work for the uplift of the community is against the spirit of representative democracy. After all, candidates are supposed to represent their voters, irrespective of religion, caste or gender.

Muslims are also under-represented in legislatures in states with substantial numbers of the community. Uttar Pradesh, home to about 40 million Muslims, does not have a single Muslim MLA or MP belonging to the ruling BJP. In the most recent Bihar Assembly elections in November 2020, not even one Muslim MLA ended up on the treasury benches for the first time since Independence. In the 230-member Madhya Pradesh Assembly, there are only two Muslim MLAs. Rajasthan’s 200-member assembly has only six Muslim MLAs. In Telangana’s 119-member assembly, there are only seven Muslim MLAs, all belonging to the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM). There is no Muslim elected member on the treasury side in all these states. In Chhattisgarh, the 90-member assembly has no Muslim representation. Many parties in Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Odisha and Maharashtra have completely excluded Muslims. In 28 state assemblies taken together, Muslims occupy only 6% of the seats.

Since 1952, one informal curative method used by political parties to balance Muslim under-representation in the Lok Sabha was to accommodate them in the Rajya Sabha. The indirect nature of election there, made it easy for political parties to get their Muslim candidates through. The average Muslim representation in the Rajya Sabha since 1952 has been 12%, which is double their representation in the Lok Sabha (Farooqui 2020). However, the BJP’s expansion has had a negative effect. In the current Rajya Sabha, the percentage of Muslims is 7%. In a break from the past, at present there is no Muslim representative in the Rajya Sabha in the nominated category, which has further depressed their numbers.

During the glory days of the Congress party, the largest number of Muslim representatives in the Rajya Sabha came from UP, and after the party’s decline they come from the SP. It is only in states like Jammu and Kashmir, West Bengal, Karnataka, and Kerala that one can expect nomination of Muslim candidates in the foreseeable future.

Causes

Christophe Jaffrelot (2019) traces the decline in Muslim representation to the ascendancy of Hindu nationalism. He argues that whenever the BJP conquers a new state, the number of Muslim MLAs comes down. He cites the example of UP where, in 2017, the proportion of Muslim MLAs fell to 6% from 17% in 2012. The latter high percentage of Muslim MLAs was owing to the large number of seats accruing to the SP, but the figure came down with the huge success of the BJP in UP.

Scholars like E. Sridharan (2002) argue that this depressed representation of Muslims is a consequence of the structural flaw in the first-past-the-post system, which is skewed in favour of majority groups, whose votes are concentrated in a geographical area, and against the representative claims of minority groups. Muslims, who are on the whole more evenly dispersed across the country rather than being concentrated in pockets, end up having fewer seats per vote (Roy 2019) and fewer of their co-religionists are elected. Omar Khalidi (1993) has noted that that anti-Muslim sentiment stoked by some in the BJP has led to fewer Muslim candidates from other parties. The Congress and other opposition parties become apprehensive that nomination of Muslim candidates would make it easier for the BJP to consolidate the voters of the majority community and emerge victorious.

It is a tricky proposition to imagine that it is the responsibility of Muslim representatives only to take up issues of Muslims. The concerns of this community are national concerns.

In view of this operational reality, it seems highly unlikely that the number of Muslim candidates will increase significantly in the years to come. They would be fielded only in seats with larger concentrations of Muslim voters. Here too, many such seats have been reserved for Scheduled Castes, limiting the number of seats where Muslims have a fair chance of being considered. For example, in UP, six constituencies with more than 30% Muslims, four with more than 25% Muslims and seven with more than 20% Muslims have been reserved for Scheduled Castes.

Constituencies have also been delimited in a manner that weakens the capacity of Muslims to shape electoral outcomes. For example, in UP, the Bareilly cantonment assembly constituency had 57% Muslims. Post the notification of the fourth Delimitation Commission’s recommendations in 2008, the constituency was redrawn in a way that the proportion of Muslims has been reduced to 35%. The Rampur assembly constituency has had the number of Muslim voters dropped by over 20% after delimitation. In Barhapur constituency of Bijnore, the proportion of Muslims has come down to less than 30% from 45% percent before delimitation (Beg 2015).

Raising issues

The scholar Iqbal Ansari (2006) argues that Muslim under-representation is the main contributory factor behind the social, economic, and educational backwardness of Muslims. Other commentators, like Adnan Farooqui, maintain that Muslim political representation is morally essential and democratically crucial.

To argue that we need Muslims in representative bodies to work for the uplift of the community is against the spirit of representative democracy. After all, candidates are supposed to represent their voters, irrespective of religion, caste or gender.

Yet, the data suggest that non-Muslim representatives were far less likely to ask questions about issues that particularly concerned the community. In a study, Saloni Bhogale (2024) picked up 1,875 unique instances of questions raised about Muslims between 1999 and 2017. Muslim and non-Muslim MPs had a share of 22% and 78% in these questions. When seen with the fact that Muslim MPs did not make up more than 6% of Lok Sabha at any period, it shows that Muslim MPs have a larger relative share in questions concerning Muslims in the House. She also points out that the low number of Muslim women – less than 1% of Lok Sabha members are Muslim women. (Since Independence, out of the 690 women MPs elected to Lok Sabha, only 25 have come from the Muslim community.) Low representation means the issues concerning this section are for the most part not likely to be raised.

To argue that numbers alone are important is quite problematic. What is more important is to see whether they are able raise substantive issue and have an effect on legislation and policy.

The issue of Muslim representation is complex, and unless political parties are willing to acknowledge that a significant marker of democratic citizenship is political representation, the issue would not be taken seriously.

Here bigger political parties make a greater impact when they raise or lend support to an issue. But Muslims elected on their tickets have much less of an autonomous say in raising issue concerning their community because their parties are extra cautious in matters concerning Muslims. Hence, their numbers in a legislative body, if large, can create an optical illusion, but at the operational level the community does not stand benefitted.

A classic example is the case of UP in 2013 at the time of Muzaffarnagar riots. At that time the state had 69 Muslim MLAs, the highest since Independence. The ruling Samajwadi Party had 45 Muslim MLAs, but few of them could speak for the Muslims who were at the receiving end of the violence, as their party decided not to speak up for fear of annoying the majority community.

Compared to legislators like them, an independent Muslim legislator or one from from a party like the AIMIM is more able to raise such issues. A leader like the AIMIM’s Asaduddin Owaisi operates in the discourse of Muslimness and becomes a representative of all Muslims, but that does not guarantee success for his party at the constituency level outside of Hyderabad. This is so, because his appeals to the broader community do not correspond to the complex sociological and economic configurations at the level of individual constituencies. Substantive Muslimness produces a different context-specific logic of representation (Ahmed 2019) and Muslims do not necessarily vote on communal lines as is generally believed. They, like other citizens, vote for similar existential issues, something which has been brought forth in several surveys conducted by the CSDS (Lokniti-CSDS, NES 2019 and 2024).

It is a tricky proposition to imagine that it is the responsibility of Muslim representatives only to take up issues of Muslims. The concerns of this community are national concerns. Nonetheless, in today’s deeply polarising political climate, it is difficult for political parties, even those which claim to be ’secular’, to even utter the word Muslim. Giving Muslims political representation commensurate with their share in the population, is something which is not politically gainful for most political parties.

Numbers in the data tell us that there is a case of serious under-representation of Muslims. The reasons for this lack are known. Yet, mere numbers are not enough; in fact, they could be deceptive. The issue of Muslim representation is complex, and unless political parties are willing to acknowledge that a significant marker of democratic citizenship is political representation, the issue would not be taken seriously.

Mirza Asmer Beg is a professor of political science at Aligarh Muslim University.