United States President Donald Trump has declared a war on the world to Make America Great Again. The rules-based order of the World Trade Organization (WTO) has collapsed. Like the big bully in the playground, Trump taunts all countries to fight him one on one. Smaller countries are tempted to make deals with him to save themselves. India must find its own way. Trump does not like India protecting its farmers and small industries. He wants the country to open its markets to large US corporations.

While India has begun negotiations with the bullying US, its leaders must not lose sight of its destiny.

India set out on a journey to its “tryst with destiny” on 15 August 1947. Citizens were promised poorna swaraj – political, social, and economic freedom. They obtained a good measure of political freedom, with equal voting rights for the rich and the poor, men and women, whatever their caste or religion. Yet, eight decades later, all citizens do not have equal economic opportunities.

Since changing the rules of the game has not been enough for the US to win, Trump has taken the ball away and abandoned the game.

Those who begin with greater social and economic endowments can more easily seize the opportunities that open markets provide. They get further ahead of those scrambling behind to catch up. Though the numbers of Indian millionaires and billionaires have increased, hundreds of millions of poorer citizens do not have decent jobs and incomes – and no social security.

India’s leaders have choices to make. Should they continue the pattern of economic policies the country adopted when its economy was liberated from industrial policy and socialism in 1991? Or should they not open their minds to other ways?

Trade policy

The United States imposed its version of a liberal economic order on the world when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. The principle-based Global Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT), which the US championed after World War II, was replaced by the rules-based WTO in 1995, along with the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). India had to abandon its policies for nurturing domestic industries, which the GATT permitted, when it turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for emergency assistance in 1991.

China, whose economy has grown five times larger than India’s since 1990, was coopted into the WTO in 2001. It has now become the second largest economy in the world and a threat to US hegemony. The US says China has not played by the rules—that it shielded its domestic manufacturers and that it stole American intellectual property. Since changing the rules of the game has not been enough for the US to win, Trump has taken the ball away and abandoned the game.

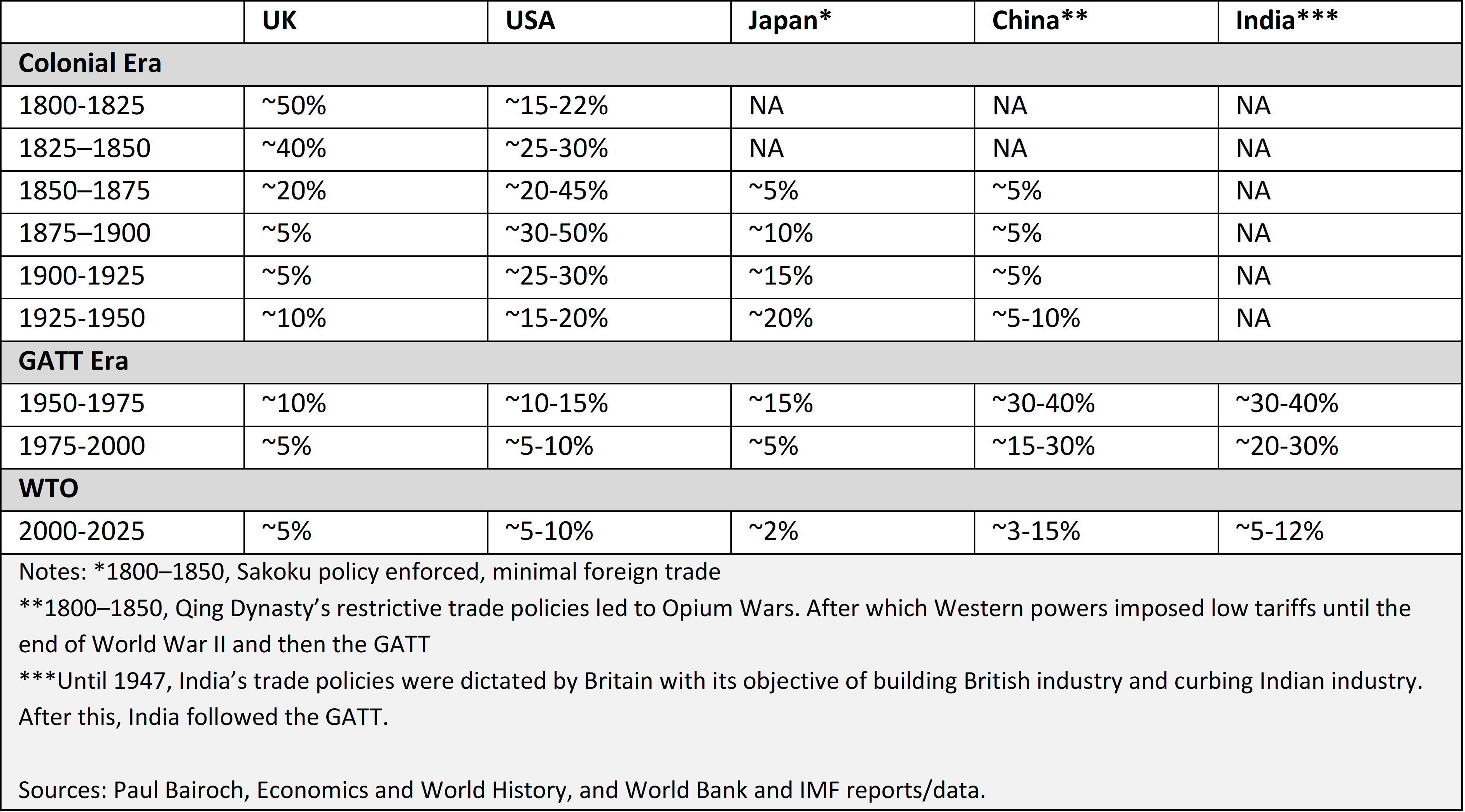

Free trade was always a myth, says Paul Bairoch in Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes (University of Chicago Press, 1993). Examining world history, he points to how the US built its industrial strength. “The most interesting period is that of the years 1870–92, those of the ‘Great Depression’ that affected the European continent, during which the United States increased its protectionism, and went through a phase of very rapid growth. Therefore, the best 20 years of American economic growth took place in a period when its trade policy was protectionist while that of the United States’ major competitors was liberal.” The history of trade reveals how Britain also built its industrial strength behind high tariffs.

Table 1: History of Tariffs: First Build, And Then Open (Average import tariffs)

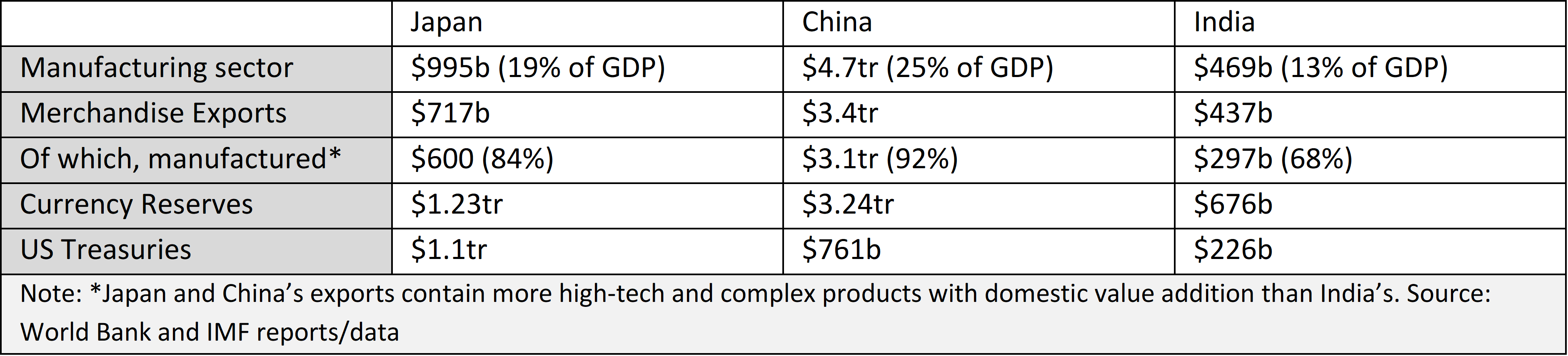

Trump’s principal target in the global trade war is China. India’s negotiators must be guided by a long-term strategy to build depth in India’s own industrial capabilities, which have lagged far behind China. China and Japan are in much stronger positions to negotiate trade deals with the US than India. The US needs Chinese and Japanese manufacturers, and China and Japan prop up the US economy by investing their huge trade surpluses in US Treasury securities.

Table 2: Comparison of Manufacturing Strengths

Industrial policy

Free trade, based on the theory of competitive advantage, theoretically benefits everyone in the long run. If every country were to produce only what it can produce better than everyone else and buy from others what they can produce better, all should benefit from access to the best and cheapest products in the world.

The problem with this theoretical view is that competitive advantages are not static, except for commodities. Industrialisation is a process of enterprises learning capabilities they did not have before. Trade management is a game of countries preserving their competitive advantage. Every country that has industrialised effectively (including the US in the 19th century) protected its industries while growing their capabilities.

China’s capital goods sector has become many times larger than India’s, and its exports of high-tech manufactured products are 48 times more—so much so they are now threatening even US industry.

Industrially advanced countries protect their monopolies of intellectual property. They prevent enterprises from developing countries from learning capabilities by raising the bogey of 'protectionist' government policies. Japan and China built the strengths of their manufacturing industries strategically. India prematurely abandoned its industrial policies in the 1990s. China’s capital goods sector has become many times larger than India’s, and its exports of high-tech manufactured products are 48 times more – so much so they are now threatening even US industry.

Japan was the first Asian power to challenge European industrial superiority. After World War II, it built its industries strategically. Industry and trade policies were coordinated by its ministry of international trade and industry (MITI) in collaboration with the country’s industrialists. By 1990, Japan had become the factory of the world for manufactured products ranging from automobiles and electronic products to precision machinery. China became an even larger factory of the world by 2010 by strategically navigating the WTO and TRIPs trade regime that replaced the GATT in 1995.

'Free' trade is never 'fair' trade. The most powerful countries set the rules and change them when they do not suit them any longer. After the WTO, industrial policies were forbidden because they 'protect' domestic industries. The TRIPS agreement protected the intellectual property of US and Western companies, which they used to control value creation in global supply chains. The US says China has cheated and 'stolen' intellectual property. The truth is that Chinese industries learnt how to produce what they could not earlier, and to do it as well as American industries.

India is at the cross-roads. Should it comply with Western trade pressures or build its industrial strengths?

India can be a huge market attracting foreign and domestic investors if incomes rise in the country and more people are employed in jobs that can improve their skills. Economies develop through a process of learning new capabilities. A country’s domestic enterprises learn to do what they could not do earlier. Workers learn new skills within enterprises. Employers should consider their employees as 'appreciating assets' who can learn new skills on the job (as Japanese and German employers do) and not as mechanical resources to be bought and discarded.

Economic development strategy

The philosopher George Santayana said in The Life of Reason: The Phases of Human Progress in 1905, “Those who forget history are doomed to repeat it.” In Economic Development: The History of an Idea (University of Chicago Press, 1989), H.W. Arndt explains, “Development as a process preceded development as a policy objective. Development had been happening for centuries in Europe before anyone consciously put forward material progress as a desirable objective of state policy.” The size of a country’s economy has currently become the all-round measure of a country’s progress.

Russia’s GDP shrank by nearly 40% between 1991 and 1998; industrial output dropped; and poverty rose, with 30% of the population living below the poverty line by the mid 1990s.

The history of wars for ideological hegemony was supposed to have ended in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the weakening of Russia. Western economists presumed their ideology of free markets and privatisation had defeated the strategies of central planning and industrial policy for building domestic capabilities. Russia complied with US economists. Its economy was reformed with a 'big bang' – with disastrous consequences. Russia’s gross domestic product (GDP) shrank by nearly 40% between 1991 and 1998; industrial output dropped; and poverty rose, with 30% of the population living below the poverty line by the mid 1990s.

China and India took different paths after 1991. India was compelled to take a loan from the IMF with conditions attached, and forced to abandon industrial policies (though not planning). It joined the WTO when it was formed in 1995, and China joined in 2001. India entered the global Information Technology Agreement in 1997 to reduce import duties on information technology (IT) products to zero, but China did so only in 2003. China did not succumb to US pressure, and continued with the development of a centrally guided 'socialist market economy'. It built its capabilities before joining the global game.

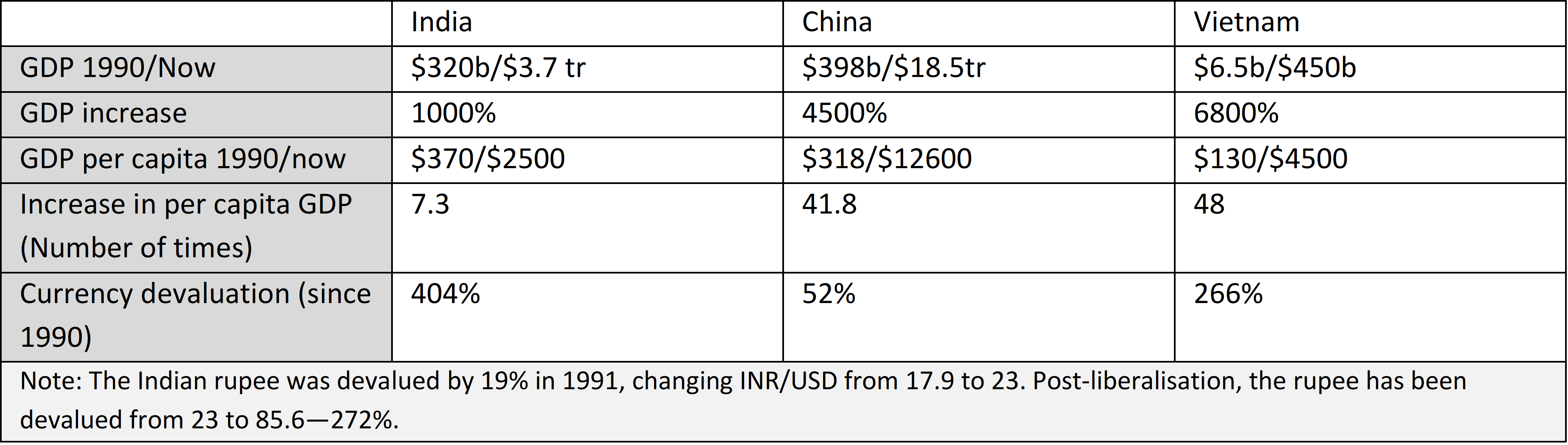

India’s aspiration for poorna swaraj, where all citizens have equal opportunities (though not equal outcomes), comes from a vision of an equitable society. Should India follow the US and Western economic ideas or take another path? A comparison of the economic histories of India, China, and Vietnam since 1990 should give the country’s reformers some pause.

Table 3: Faster and More Inclusive Growth

Per capita GDP is what matters to citizens, not total GDP. The value of its currency indicates the overall strength of the country’s economy compared to others. Incomes have grown much faster in China and Vietnam, and their currencies have remained stronger – China’s much stronger. They did not succumb to US pressure to give up their socialist moorings and their policies to build domestic industries when they joined global trade. History suggests that India gave up too soon on industrial policy, moved too fast to liberalise trade, and prematurely abandoned socialism for capitalism.

China’s economic growth in the last 40 years, from a very poor country to an economic powerhouse contending with the US, is remarkable. The country’s growth is a paradox for Western economists who believe that economic growth must inevitably lead to democracy. China has remained stable, ruled by a single party, as it grew. But the multi-party democratic fabric of the much richer US is being torn apart.

Communist China escaped the shock therapy the IMF imposed on communist Russia in 1992 with catastrophic effects. China continued on its own path of reforms, adopting capitalist tools without abandoning socialist ideology. Isabella M. Weber says, in How China Escaped Shock Therapy: The Market Reform Debate (Routledge, 2021), “The famous Harvard development economist Dani Rodrik represents the economics profession more broadly when he answers his own question of whether ‘anyone (can) name the (Western) economists or the piece of research that played an instrumental role in China’s reforms’ by claiming that ‘economic research, at least as conventionally understood’ did not play ‘a significant role’ [The Past, Present, and Future of Economic Growth, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2010].”

China’s growth is a paradox for Western economists, says Linda Yueh in China’s Growth: The Making of an Economic Superpower (Oxford University Press, 2013). “China’s context further confounds straightforward interpretations of the theories that link ‘openness’ to the global economy with economic growth. A key theme of the book is that the structure of the economy is as important as the standard growth factors. And the best view of the structure is from the microeconomic perspective of firms and households.”

China’s market reforms began bottom up, from town and village enterprises, first in rural areas and then cities. Private enterprise was introduced gradually at the bottom first, alongside a state sector that controlled large industries.

Deng Xiaoping launched China’s ongoing process of economic reforms to “markets with socialist characteristics” in 1978 with the slogan “Practice is the sole criterion for testing truth.” He adopted a scientific approach to the process of transformation, of learning through small-scale experiments to test the results from new ways, rather than adopting supposedly scientific – and contextually inappropriate – Western economic theories. “It does not matter what colour the cat is so long as it catches the mouse,” he said. Also, “We will find our way by feeling the stones under our own feet.”

China’s market reforms began bottom up, from town and village enterprises, first in rural areas and then cities. Private enterprise was introduced gradually at the bottom first, alongside a state sector that controlled large industries. Entry of foreign firms was regulated through joint ventures and other legal arrangements that enabled the transfer of technology. China became the highest recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI), even catching up with the US, even though it ranked low on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business rankings.

Yueh says China’s remarkable growth story “does not fit well into the studies of institutions and growth. The rule of law and other market-supporting institutions, such as private property protection, are weak, and there is no independent judiciary.” Yet, foreign companies were rushing to cash in on the economic opportunities China provided them on both the demand and supply sides.

China is a more appropriate source of ideas for India to achieve rapid and inclusive growth than Western academia and institutions. India need not, and should not, adopt a single party governance system. Both the Indian National Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have followed the Western model of market economics. The Congress introduced it in 1991 and the BJP has continued with it. The time has come for a political consensus on a new model for the Indian economy – one that is not guided by Western ideas, which are not working even in the West.

India, the world’s largest electoral democracy, has a difficult relationship with the US. The US expects India to always be on its side against any authoritarian country unwilling to toe its line. It had considered India immoral for remaining neutral between the Soviet Union and the West in the Cold War. Trump seems willing to make up with Russia now, but not with China, which has caught up with the US in advanced technologies.

The US and China are India’s largest trading partners, with $118 billion trade with each. Whereas India has a trade deficit of $85 billion with China, from where it imports large volumes of manufactured goods, it has a surplus of $37 billion with the US, which is its largest market for software services. India must tread carefully, and annoy neither the US nor China. On its northern border, where tension continues to simmer, is China. At the same time, despite Trump’s pressure to continue with the defunct Washington formula, India has to build its own industrial capability.

While China did not adopt the US idea, India complied easily. Now India, like the US, is importing a large range of manufactured products from China, including high-tech ones.

India’s and China’s manufacturing sectors were similar in 1990. India had established better capabilities in the production of machinery, electrical equipment, commercial vehicles, and other capital goods. Indian made trucks and power equipment was exported to many countries. But the IMF assistance in 1991 ushered in the Washington formula. While China did not adopt the US idea, India complied easily. Now India, like the US, is importing a large range of manufactured products from China, including high-tech ones.

Trump says India’s import duties are too high and must be reduced across the board. He wants India to cut duties on all manufactured products to make life easier for US companies, and also on agricultural products so that America’s highly subsidised, corporate farmers can expand their markets in India. India must resist because its millions of poor farmers and workers need higher prices and higher wages to improve their standard of living.

Indo-US trade negotiations have begun with a declared aim of increasing bilateral trade to $500 billion annually by 2030. With India being threatened to lower its barriers to imports of US agriculture and manufactured products, and apprehensions of dampers on its IT exports to the US, bilateral trade can be increased only by a huge increase in imports from the US. This will lead to a decline in the growth of jobs and incomes in India, weakening its economy.

Indian industries have been hoping that US restrictions on Chinese imports will result in openings for them in US supply chains. Alongside, with Trump raising import duties on China to 125%, other countries fear that Chinese manufacturers will aggressively sell their products to them instead. Indian businessmen are already pressing the government to make it easier for them to import Chinese products. To import and sell is easy. Learning to make in India is harder.

The time has come for India’s manufacturers to support the Indian government and unite against bullying by Trump and US corporate interests. All who care for the well-being of India and its citizens must work harder together to build the country’s industrial capabilities and create more dignified employment opportunities for its people.

Arun Maira is a management consultant and a former member of the Planning Commission. His book, Reimagining India’s Economy: The Road to a More Equitable Society, will be published in May 2025 by Speaking Tiger Books, New Delhi.