Questions have been raised about the recent sharp rise in rural female work participation rates in the Periodic Labour Force Survey of 2023-24, suggesting that this may be due to new instructions to field staff on enumeration or definitional change.

This note takes a critical look at the points raised in the recently published article in The India Forum: "The Rise in Female Labour and Work Force Participation Rate". While appreciating their careful deconstruction of the instructions, it is necessary to point out some misinterpretation of the changes made in the ‘Instructions to Field Staff’ for the PLFS 2023-24 (henceforth called ‘Revised Instructions’) and identify the possible effect of these additional ‘clarifications’.

Since the beginning, the PLFS has used the same instruction manual for the field staff. Some specific clarifications have been inserted in the 2023-24 instructions possibly prompted by field queries received during the earlier rounds of the survey.

The authors have misinterpreted these clarifications as a change in the definition of the ‘worker’ and the criteria for identification of persons engaged in economic activities. Nevertheless, the authors’ observations on the effect of inclusion of this ‘extra care and precision’ in the Revised Instructions, especially those noted on pages C-55 --C-58 of the instruction manual need to be examined assuming that field staff paid extra attention to these clarifications.

1. Definition and methodology

The definition of ‘activity status’ in the Revised Instructions (pages A-13 to A-16) is exactly the same as that given in previous years.(“Instructions to Field Staff: Design, Concepts, Definitions, and Procedures, 2016”, pages A-13 to A-17).

The definition of ‘work’ in the PLFS is aligned to the definition of the production boundary adopted in the Indian System of National Accounts (ISNA), which, in turn, is an adaptation of the definition recommended in the System of National Accounts (2008 SNA) 1The main departure made in the ISNA from the 2008 SNA, in this context, relates to treatment of the activity called ‘custom tailoring’. According to the International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities Revision 4 (ISEC) custom tailoring is included in the manufacturing sector, while in the INAS it is treated as a service. Thus, the activity of tailoring for household’s own use is not treated as an economic activity. . The production boundary of the 2008 SNA includes (i) all activities of production of goods, (ii) service-providing activities carried out for the market and (iii) own-account production of housing services by owner-occupiers, domestic services employing hired staff and services for creation of intellectual property products for capital formation. Typically, the scope of labour force surveys covers activities of the kinds (i), (ii) and own-account production of ‘domestic services employing hired staff’.

Thus, in the PLFS, production of services for the household’s own consumption, such as sewing, tailoring, weaving for own use, is not treated as an economic activity. On the other hand, (a) small-time agricultural activities of working in the kitchen garden, orchards, household poultry, dairy, even if they are meant for household’s own consumption, (b) preparation of processed food for sale, (c) participation in the activities of households’ market enterprises, and (d) free-collection of goods for sale are treated as economic activities. The free collection of goods for households’ own consumption, which is included in the production boundary of the ISNA, is also treated as an economic activity in the PLFS. Participation in production of goods and services for the market is always treated as economic activity.

There are two separate codes for those reporting domestic work as their principal activity -- Code 92: attended domestic duties only and Code 93: attended domestic duties and was also engaged in free collection of goods, tailoring, weaving, etc., for household use

The idea behind including these two separate codes was in recognition of the possibility of people, particularly women, performing economic activity on a minor scale in addition to their household chores. This also ensured better recognition and reporting of subsidiary activity of women reporting code 93. In past employment-unemployment surveys, a set of probing questions used to be asked of those reporting principal status codes 92 and 93 in order to report specific activities of economic benefits to the household. The widening of the economic activity boundary in the 1990s 2Instructions to Field Staff of the Employment and Unemployment survey of NSS 55th round (1999-2000) clearly states that gathering of uncultivated crops, forestry, collection of firewood, hunting, fishing etc., even if for own consumption, were treated as economic activities. has meant most of these are now within the boundary of economic activities.

The subsidiary status activities are actually reported for all, including those employed according to their principal status, as they might have another activity outside their main employment. While estimating the worker population ratio (WPR) only those of subsidiary work status are counted whose principal activity is other than working. The data shows that subsidiary work activities are significant only of those in status codes 93, 92, 91 and 94 (in that order) 3These activities are 91: attended educational institution, 92: attended domestic duties only, 93: attended domestic duties and was also engaged in free collection of goods, tailoring, weaving, etc., for household use, 94: recipients of rent, pension, remittance, etc. .

These would be retired persons or students undertaking part-time work during the reference period, or women in the household helping in the household farm or business in addition to their household chores. The examples in the latest instructions (C-55--C-58), possibly intended to ensure better recording of subsidiary statuses, unwittingly change the principal status of some outside the workforce from codes 93 (‘also engaged in free collection of goods, tailoring, weaving, etc., for household use’) to 92 (‘attended domestic duties only’). This actually serves no purpose in the determination of workers either according to the principal or subsidiary status.. However specifying examples this way sometimes can lead the field staff to take extra care in probing, depending on their understanding, especially when the training for the survey is organised in a decentralised way as it happens in the National Sample Survey Organisations (NSSO) and fresh set of investigators are deployed each year.

We examine if the WPR has been affected due to the new instructions boxes.

2. Workforce estimates of PLFS 2023-24

Effects on Usual Status Estimates

Though the Revised Instructions do not make any definitional change, one need not discount the impact of the additional stress laid through the examples in the instructions.

The PLFS estimate of the number of workers according to the usual status can be split into three distinct non-overlapping components, namely (i) the number of persons working according to principal status only (ii) the number of persons working according to subsidiary status only and (iii) the number of persons working according to principal status along with work in subsidiary capacities (though their principal status work activity alone would be counted for work participation rates).

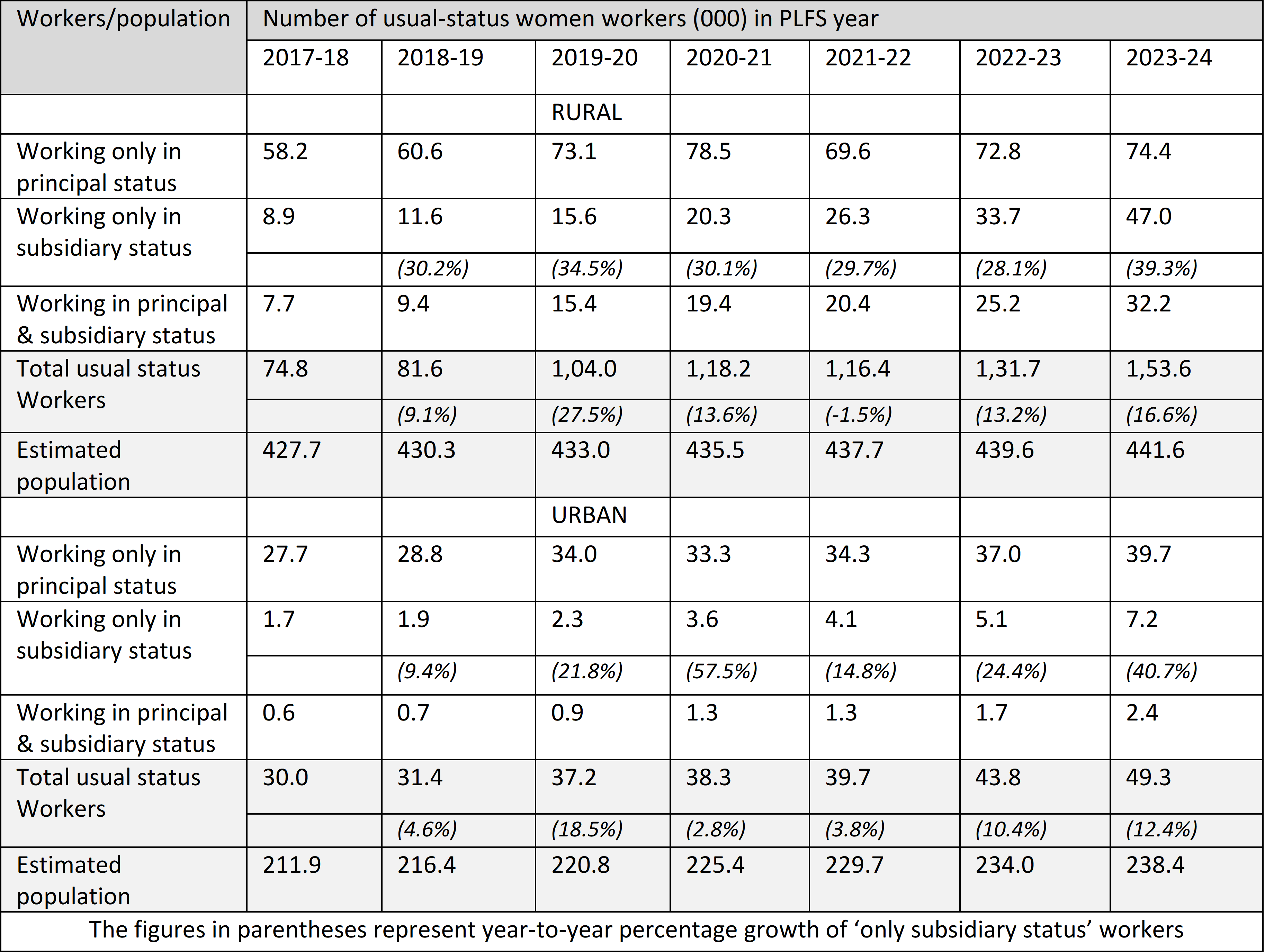

Table 1 presents the estimated number of rural and urban women workers in usual status by the three components separately. The numbers are estimated from unit-level data and adjusted by the population projections. It shows that the estimates of the women workforce have grown by about 98 million during the seven-year period, of which 80% is accounted for by rural women. Close to half of the growth in both rural and urban women workforce occurred in the last two (post-Covid) years.

Table 1: Number (million) of rural and urban women workers in usual-status by constituent categories (2017-18 to 2023-24)

One does notice a significant rise (39.3%) in the subsidiary status employment of rural women in 2023-24, compared to the steady annual growth of around 30 percent noted in recent years. An increase though not as pronounced, is observed in this component of the urban women workforce as well.

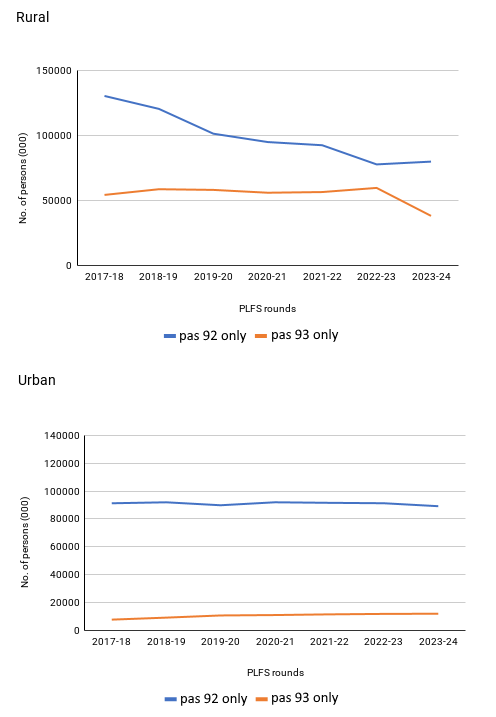

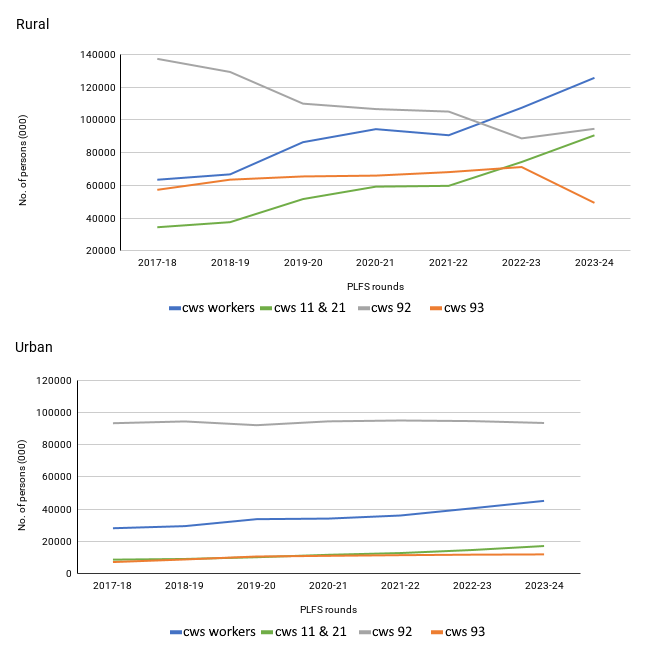

As noted, the new instructions are bound to reduce the reporting under status code 93 by forcing / shifting some from this category to status code 92. This is seen from Figure 1 for the rural female respondents. For the urban women, the estimates of these two categories do not vary much; the respondents under status code 93 being too low to capture the change.

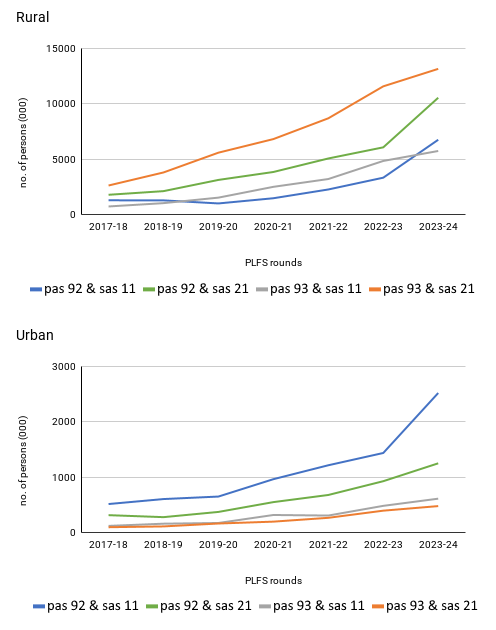

Second, assuming that the investigators have paid extra attention to the examples in the instructions, we can expect to see an increase in the number of women classified under activity code 92 by principal status (domestic duties only) and their subsidiary status as working. This is what has happened. There is an increase in the number of women with 92 as principal status and secondary activity status 11 or 21 accompanied with a in the number of women with principal status code 93 and secondary activity status codes11 or 21. (Activity code 11 refers to own-account activity and 21 refers to unpaid family work activity.)

Figure 2 shows that this happening to an extent.

Figure 1: Trend of number of women in principal activity status (pas) 92 & 93 with no subsidiary activity status (sas)

Figure 2: Trend of number of women in principal activity status (pas) 92 & 93 with subsidiary activity status (sas) 11 & 21

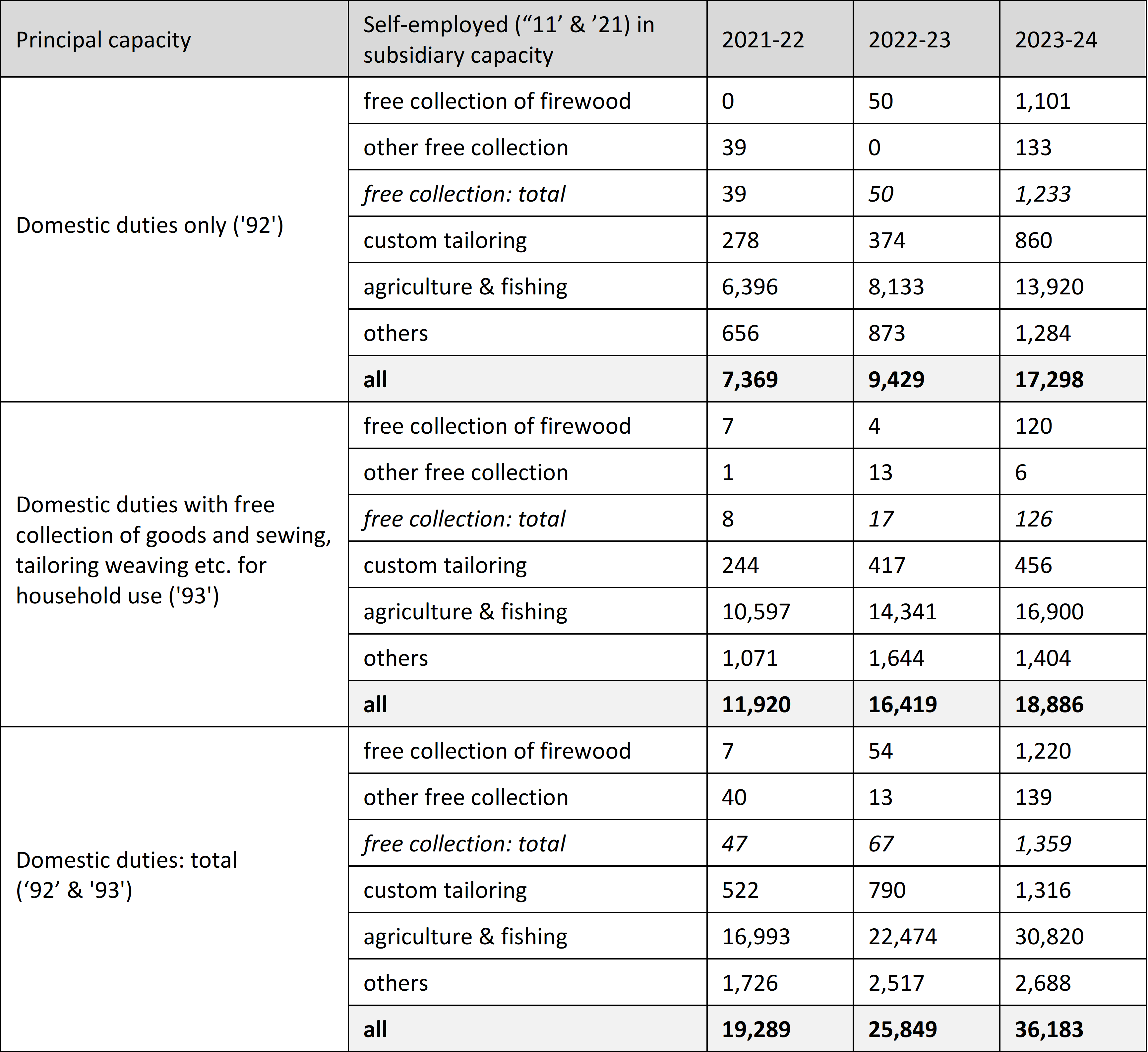

When we compare the estimates of the rural women principally engaged in household chores with self-employment in subsidiary status by the industrial classification in 2022-23 and 2023-24 (Table 2), we do find a jump in the rural women reporting gathering of firewood, as well as participation in agriculture and fishing and custom tailoring in subsidiary capacity.

The increase in the number of women gathering firewood in the face of extensive provision of cooking gas cylinders to rural households goes against conventional logic. However, with the growing participation of women in marginal agricultural activities and a general rise in their engagement in custom tailoring, the high growth in participation in these activities in subsidiary capacity of women principally engaged in domestic duties between 2022-23 and 2023-24 does not seem to be unlikely. Yet, the increase in these activities and the stress on free collection in the examples of instructions to the field staff do suggest that investigators have made special efforts to enquire about them during the interview.

Table 2: Number of rural women workers (000) engaged in domestic duties in principal capacity with self-employment in subsidiary capacity by activity class in 2021-22 to 2023-24

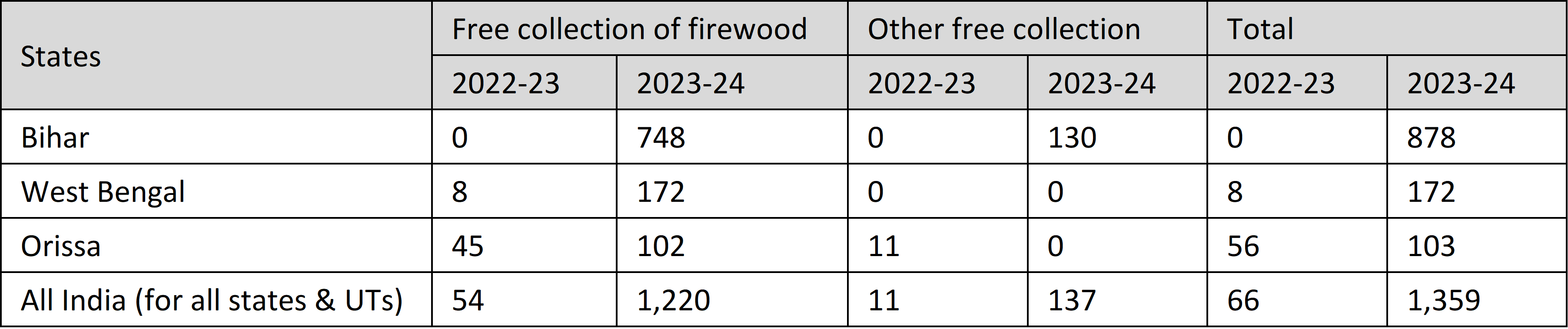

The industry description (National Industrial Classification 2008) of the activities showing any abnormal growth between 2022-23 and 2023-24 would provide more conclusive evidence on the impact of the new clarification. Table 3 shows the number of rural women with principal activity status code 92 or 93 reporting free collection of firewood and other goods (NIC 02201: free collection of firewood, NIC 02301: free collection of tendu leaves, NIC: 02303 free collection of mushrooms and NIC 02309: free collection of non-wood forest products not elsewhere classified).

Table 3 reveals that the three states of Bihar, West Bengal and Odisha account for almost all the increase . In fact, for Bihar the estimated number of rural women engaged in free collection of firewood in the principal status (not presented in the table) too shows a ten-fold rise to 3.3 lakh in 2023-24. This sudden jump in the recording of activities involving free collection appears to be a result of the stress given in the examples on free collection for those reporting status code 93 in their principal status. As noted, the examples in the instructions would have led to a modification of the status code from 93 to 92 for many. In these three states the overriding impact appears to be the jump in the recording of activities involving free collection of firewood, leading to enumeration under code 93.

Table 3: Estimated number (000) of rural women with principal activity status 92 or 93 reporting free collection of firewood and other goods

3. Effect on Current Weekly Status Estimates

The situations noted in the newly added examples in the instructions are meant mainly for the recording of the usual status.. For the daily status, which is more disaggregated in nature with a short interval of a half day, these instructions are not supposed to have any impact. The current weekly status work participation, derived from the daily statuses recorded for each of the seven days of the week, gives us an alternate indicator to look at. The questionnaire provides for recording two distinct activity statuses for each day and thus has the scope for separately recording economic and out-of-labour force activities . Thus, missing the marginal economic activities, such as free collection, participation in the household enterprise as a helper and working in the kitchen garden and caring for the household’s livestock, is just as unlikely in the PLFS 2023-24 as in the earlier rounds of the survey. There should be hardly any effect on the estimates of WPR by current weekly status.

Figure 3: Trends in current weekly status (cws) women workforce and engagement in domestic duties

These are clearly borne out by the estimates of the number of working and out-of-labour force rural women plotted in Figure 3. However, there is virtually no sign of any effect of the clarifications on estimates for the urban women

The overall work participation rates for rural women went up from 20.7 per cent in 2021-22 to 24.4 per cent in 2022-23 and is now 28.4 per cent in 2023-24 (Statement 3 of PLFS 2023-24 report). This would imply that the usual status WPR increase cannot be attributed to the amplification of the instructions.

4. Conclusions

An increasing trend in the work participation rates of rural women has been observed especially after Covid.. The latest PLFS survey also shows this trend. Our analysis indicates that this is not a direct consequence of the change in instructions. A careful reading of the examples added in the instructions makes it clear that these are not any changes in the identification criteria of workers, but illustrations to make the instructions easier to understand. The question remains if these have led to an increase in female rural workers even if partially, due to the field staff placing extra stress on these clarifications. Our analysis shows that in three states there is a sudden rise in reporting of activities under the free collection of firewood category. But these are not sufficiently large to make an impact on the overall work participation rates.

Assuming that the identification of principal activity status of the persons is unaffected, what matters in determination of usual activity workforce is the subsidiary status component. This component accounts for, respectively, about 20 per cent and 10 per cent of the usual-status workforce among the rural and urban women. The growth rate of the rural female workforce is higher by about 10percentage points in 2023-24 than that in the preceding few years and the urban growth rate is higher by about 15 percentage points in 2023-24 . Thus, the effect of the possible extra stress on identification of free collection and marginal agricultural activities would at the most be of the order of 2 and 1.5 percentage points in the observed growth rates of 16.6 per cent and 12.4 per cent, respectively, for the rural and urban women. This is if we attribute the incremental growth rates solely to the effect of the extra stress placed on identification of free collection and marginal agricultural activities, and would be an upper limit of the effect of new instructions. Thus the overall impact on the growth in women’s employment is not very high on account of the changes.

In a large economy with high levels of informality in employment with many activities lying on the employment boundary, a simple definition to identify persons as employed is not really an option. Most often the attachment is marginal in terms of the time spent. The Indian employment surveys have accepted this since the beginning, resulting in different approaches to measure employment. These, in turn, lead to a rather complex set of instructions for the investigators.

The discussion here shows the need to be extremely cautious in making changes in the instructions or providing imaginative examples for the benefit of the enumerators. In large-scale sample surveys spread over the country using the services of hundreds of investigators, one cannot be very sure that the intent of any clarification will be understood uniformly. In the present case, the use of the word “free collection” appears to have caught the eyes of the investigators. One cannot be very sure how the time criterion for assigning the work status to this activity was applied in the field. However, the increase in WPR that can be attributed the new instruction boxes in the manual does not appear significant, given that the weekly status criteria also points to an increasing trend in women’s WPR.

P C Mohanan (parachottilmohanan@gmail.com) retired from the Indian Statistical Service and served as Member of the National Statistical Commission. Currently he is Chairman, Kerala State Statistical Commission.

Aloke Kar (alokekar@gmail.com) a former member of the Indian Statistical Service served with UN Statistical agencies including the Statistical Institute for Asia Pacific. He is currently associated as a Visiting Scientist with the Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata.