The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 envisions transforming colleges into hubs of knowledge creation by introducing research at the undergraduate level. While this is an ambitious and commendable goal, it faces significant challenges. Most undergraduate colleges are primarily teaching-focused, with limited human resources and funding to support meaningful research.

While structural constraints to such aspirations are critical, we focus here on the pedagogy of research methods, emphasising its crucial role for first-time researchers. Notably, in the United States – which appears to have influenced the NEP – students are introduced to research at the school level. In contrast, Indian students often encounter research for the first time in college, making the way it is taught especially important. Yet, the NEP does not provide details on how research should be taught.

This lack of clarity suggests that students may only be given a theoretical understanding of standard research methods. However, the first step in rethinking research pedagogy is to recognise that research methods are not just decontextualised technical skills. Rather, they are deeply shaped by the contexts in which research is conducted. This is well known: the University Grants Commission acknowledges the historical and geographic roots (primarily North American) of current methods in social sciences. Methods are constantly invented, adapted, and transformed to align with the nature and context of the inquiry. Therefore, instead of simply replicating existing methods, the pedagogy of research methods should push for methodological innovation and critical thinking in research design.

These innovations should be rooted in debates on diverse ways of knowing and their broader societal impact. For instance, what does research mean for a rural Indian college? How does research in such a college engage with the local community? A research methods pedagogy built on this perspective would critically examine the politics, philosophy, and social transformations tied to knowledge creation. Such a pedagogy would also align with other critical goals of NEP 2020 (more on which in the next section), including centring local knowledge, promoting different languages, and fostering interdisciplinary engagement.

Since much of NEP 2020 is supply driven rather emerging from local demands, a top down standardised approach will be another problem. What we need is a context-sensitive way for designing such educational practices that empowers college faculty rather than treat them as agents of implementation. We see merits in utilising participatory design research, which involves students, teachers, and community members in shaping educational processes, rather than leaving this task to researchers and bureaucrats alone.

The setting

To explore this approach, we conducted an experiment in Pithoragarh, Uttarakhand, where we designed a qualitative methods workshop, aimed at testing its potential to meet the goals of NEP 2020. We selected a state-affiliated remote college because it primarily serves students from low-income and marginalised backgrounds. This made it an ideal setting to examine how ambitious policy changes could impact non-elite government institutions, which continue to struggle with basic infrastructure, faculty shortages, and access to learning materials.

Our design team, which consisted of a local student group, college faculty, and researchers, worked for a year to craft a workshop that aimed to integrate several of NEP’s objectives with what would be meaningful for students. Together we designed a curriculum and set of activities that resonated with lived reality of students as well as well as align with institutional and academic requirements. The workshop, held in October 2024, was attended by 35 participants from diverse disciplines, primarily undergraduate and masters’ students.

We designed the workshop in three distinct phases, each aligning with the vision of a context-sensitive approach. The first phase aimed to familiarise participants with the broader purpose of research and its social relevance. Students engaged in reading academic papers, brainstorming topics, and crafting a short proposal for their chosen topics. In the second phase, they focused on primary data collection, where they gained insights into research methods, developed interview protocols, and conducted interviews. The final phase emphasised data analysis: students coded their data, identified emerging themes, and presented their findings through research posters at a college-level exhibition.

In keeping with NEP 2020’s emphasis on interdisciplinary research, students were grouped across disciplines and groups had a mix of undergraduate, master’s, and senior students. The diversity in academic levels promoted internal mentorship, with senior students guiding their peers through more complex tasks.

Critical reflections on the local

Teaching research methods offers an opportunity to critically engage with the nature of knowledge itself, questioning how it is created and whose perspectives are valued. While NEP 2020 emphasises Indian Knowledge Systems, much of the focus within current academic frameworks remains on ancient, Vedic traditions. This often overlooks the dynamic, community-based ways of knowing that thrive in diverse, ecologically rich regions like Pithoragarh.

The focus should be on developing research thinking rather than replicating rigid report templates.

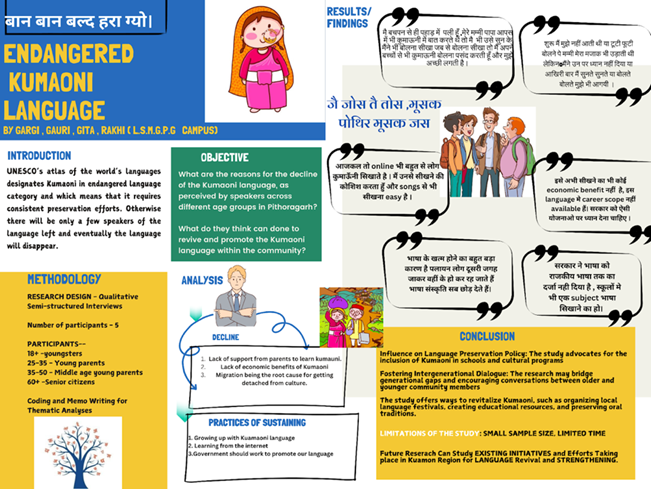

The workshop engaged students with local issues by introducing them to research and researchers focused on topics relevant to Uttarakhand. For example, Ruchika Rai shared her work on the Kumaoni Ramleela, while Radhika Govindrajan discussed human-animal conflict in the region. This exposure allowed students to select research topics that resonated with their own lived experiences and local contexts. By centring these topics, the workshop emphasised how research can serve as a tool for community empowerment, a core tenet of NEP’s vision.

In the process of identifying and analysing local issues, students also highlight power dynamics, marginalisation, and resistance. For instance, when students select topics such as caste discrimination, women in STEM, or menstrual taboos (as seen in their research posters), they are not merely studying abstract concepts. They are also engaging with real-world inequalities, challenges, and cultural shifts that impact their surroundings. This fosters critical thinking, enabling students to question dominant narratives, uncover gaps in existing knowledge, and situate their inquiries within broader societal debates.

“Before this, we would casually talk about caste with friends, but designing the questionnaire helped us gain clarity on the aspects of caste we wanted to explore,” a participant told us. By encouraging students to tackle pressing issues, research methods not only empower them to engage with local knowledge but also push them to confront the complexities and contradictions within their own communities.

Multiple languages and community engagement

The workshop actively encouraged the use of multiple languages, aligning with NEP 2020's emphasis on promoting multilingualism. While class discussions were primarily conducted in Hindi and English, students also incorporated Kumaoni to conceptualise their findings for their research posters. Many groups interviewed community elders in local languages, ensuring that these voices were represented in their presentations.

This approach highlights how research pedagogy can connect students to their communities, opening transformative possibilities. For students in Pithoragarh, engaging with elders during data collection served more than academic purposes—it was a means of reconnecting with traditional knowledge and wisdom. This process not only contributes to preserving cultural heritage but also addresses pressing contemporary issues. One group, for instance, focused on perceptions of the decline of Kumaoni, and during the exhibition, an audience member even requested that they present their findings in Kumaoni.

A major learning for our design team, and something we aim to emphasise in the second iteration of the workshop, is the need to address how research methods interact with local cultural norms. One student shared an experience of interviewing a local shopkeeper, where the conversation shifted unexpectedly as the shopkeeper asked numerous cross-questions. The student initially felt that the interview was unsuccessful, believing it had deviated too far from the planned questionnaire. However, upon reflection, it became evident that the shopkeeper’s questions were a natural part of the cultural exchange, where reciprocal curiosity and personal connection are valued in local conversations. This experience highlighted the importance of framing the interview method as emphasising mutual exchange and co-creation of knowledge, rather than adhering to a one-directional extractive approach. This insight underscores the broader argument that research methods need to be adapted to, not merely replicated in, diverse cultural contexts.

Outcomes

Promoting research as just another project report that the faculty will grade them on can feel alienating. To make sure that research becomes a form of social action, we concluded the workshop with an open exhibition. Creating research posters not only introduced students to professional practices but also challenged the convention of research outcomes being confined to academic circles. By inviting students, faculty, and external members to engage with the student posters, the exhibition became a platform for broader discussions on critical local issues, fostering feedback from diverse perspectives.

A student reflected, "Some audience members were so excited […] they shared their YouTube pages and suggested that we share our poster there." Such interactions led to meaningful exchanges, where the poster served not as the final word on the topic but as a catalyst for ongoing knowledge creation and dialogue.

Our experience highlights the need to broaden what counts as a research outcome, especially for undergraduate students. Multimodal formats like posters, short films, podcasts, or performance art can make research more inclusive for both students and audiences. At this level, the focus should be on developing research thinking rather than replicating rigid report templates. For those interested in writing, we need platforms that nurture their early ideas and pilot studies, rather than expecting them to publish in standard journals. This also requires spaces that showcase research in multiple languages. In our case, we connected students to a college-run journal that publishes short articles in various languages.

Broader reforms needed

By focusing on pedagogy, we can not only increase student engagement with research but also align with key goals of NEP 2020. Our experience with participatory design research (PDR) shows the importance of involving both faculty and students in shaping research pedagogy.

We see the potential for scaling initiatives such as these to strengthen the research culture NEP envisions.

While pedagogy is essential for supporting research, it must be accompanied by broader structural reforms to address the challenges faced by state universities and their rural campuses.

For the workshop, we adopted a model where advanced doctoral students from various institutions partnered with local faculty and community members. This approach offers a potential solution for public universities facing resource constraints. By expanding the pool of teaching resources, the model provides students with mentorship and individualised guidance, fostering a more inclusive and sustainable research culture.

However, we need mechanisms to incentivise faculty to engage in such partnerships, who are currently overburdened with teaching and administrative work. Even in our case, while many faculty members expressed interest to join the workshop, some found it difficult to take on extra labour due to their already heavy workload. Many faculty members are eager to engage in pedagogic innovation and research partnerships. However, with the increasing reliance on contractual positions, it is unrealistic to expect them to shoulder the full burden of policy ambitions. We urgently need systems that recognise and support faculty in taking up this work.

Research takes time, and meaningful insights often require extended engagement. In our workshop, students had extremely short time for data collection and another for analysis. Working in groups allowed them to engage with more data than they could individually, but this came at the cost of depth. Our priority was introducing them to the full research cycle rather than intensive exploration. We also observed how students and teachers were constantly juggling classes and assignments, making time a persistent challenge. Even with a three-to-six-month timeline, this constraint would remain. Colleges may need to reduce traditional coursework or reorient them in a way to create space for meaningful research engagement. In addition to this, targeted faculty training should be undertaken to guide research activities. While pedagogy is essential for supporting research, it must be accompanied by broader structural reforms to address the challenges faced by state universities and their rural campuses.

Gautam Bisht is a PhD student at Northwestern University. Gaurav Joshi is a faculty member at LSM College, Pithoragarh, Uttarakhand. Mahendra Rawat is a PhD student at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru. Shivam Pandey is a PhD student at the Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati.