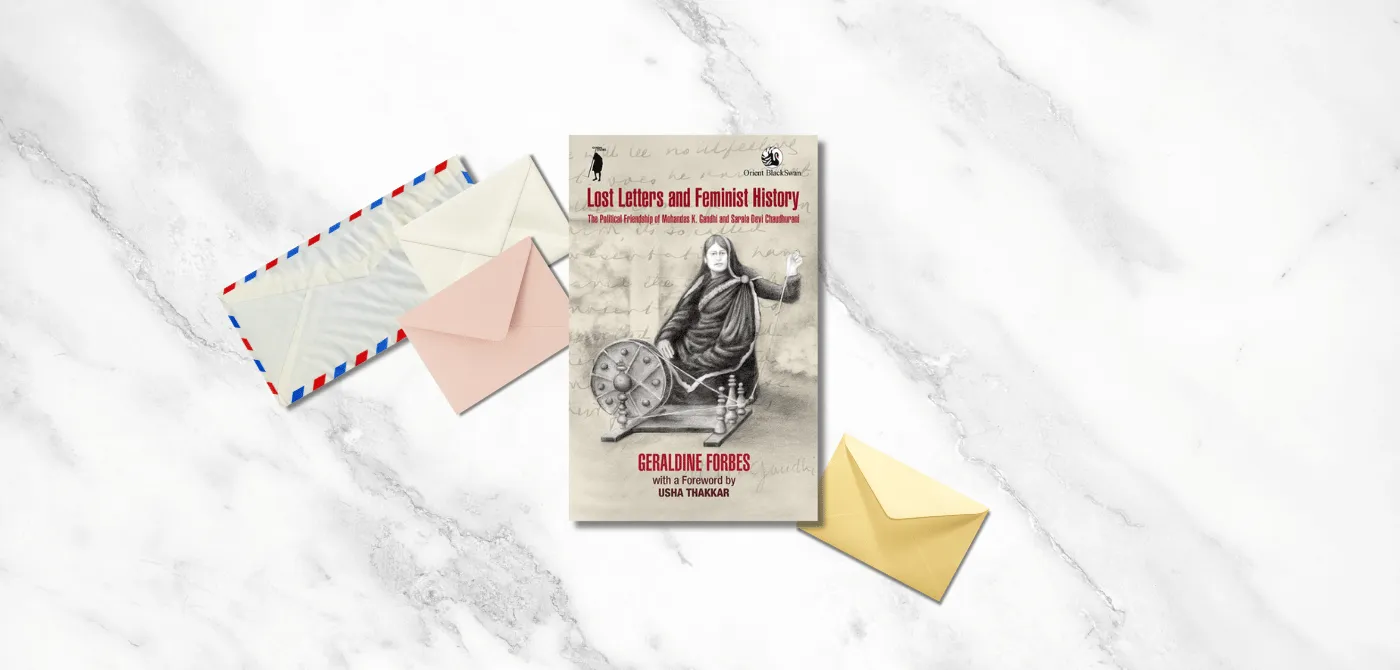

This year saw the arrival of two interesting volumes which, read side-by-side, have much to tell us about Gandhi, primarily because neither centres him. One is a book I had been waiting for since its first instalment came out in 2019 – the second volume of Manu Gandhi’s diary, The Diary of Manu Gandhi 1946-1948, translated by Tridip Suhrud. The other is a new paperback edition of Geraldine Forbes’ masterful Lost Letters and Feminist History: The Political Friendship of Mohandas K Gandhi and Sarala Devi Chaudhurani.

There are two reasons I speak of these as sister texts. First, they approach aspects of Gandhi’s life and world which may have been theorised before, but, until now, with the publication of these volumes, mostly without any kind of primary sources to ground these exercises in. Both books are therefore a profound and welcome contribution to conversations which continue to circle around Gandhi pertaining to his ‘intimate’ life, adding to literature which scrutinises his relationships with everyone from his son Harilal (Dalal 2007) to his dear collaborator and companion Hermann Kallenbach (Lelyveld 2011).

Second, while a lot of this work is nuanced and well-researched, this corpus also contains what can only (charitably) be described as fantastical takes on Gandhi’s relationships with Kasturba, Mirabehn, or Manu, to name only the best-known examples of this genre. Most texts foreground the Gandhi figure, reading the lives around him as incidental, to be parsed as carriers of meaning, read only in relation to the man they are meant to illuminate (yet) another facet of. This approach turns the other person in this relationship into a passive recipient, in contrast to the active agent s/he was: living, thinking, oftentimes challenging Gandhi in ways we are not used to acknowledging. Both texts I reference here are outliers in that they recognise that the self is slippery, constructed and re-constructed repeatedly, in concert with (and sometimes, in opposition to) other selves in our orbit. In countenancing this simple truth, they permit us to see and hear the women at the heart of them as sovereign entities.

I am not implying that Manu and Sarala Devi Chaudhurani shared characteristics. They could not be more different – and what they appear to have meant to Gandhi’s scheme of things, likewise. The parallel I draw – and celebrate – is the treatment (agentive, purposeful, complex) both texts accord these women, who wound up instructing Gandhi, even as they were instructed by him. I shall now turn to Lost Letters for the remainder of this review.

***

Geraldine Forbes plays us in and out of the core of Lost Letters – Gandhi’s letters to Sarala Devi Chaudhurani – with introductory chapters on both protagonists and a conclusion analysing the tenor of their relationship. These chapters couch the almost feverish set of letters Gandhi wrote to Sarala Devi over the course of a few months in 1920, following which their correspondence and the relationship that occasioned it both, we are given to understand, tapered off.

Forbes begins by exploring the problems which emerge from working with ‘incomplete’ archives. While scores of Gandhi’s letters to Sarala Devi exist – made available to Forbes by the latter’s family and other archival sources – we have access to barely a handful of her responses (five, not cited by Forbes). This leaves us with a dangling half-conversation. We are told that Sarala Devi’s letters to Gandhi, which had been in his son Devdas’s possession, were destroyed by his wife Lakshmi, following Devdas’ death.

On reflection, might not the attitude of Gandhi’s followers be read as yet another example of how Gandhi has been reduced by so-called Gandhians; force-fitted, into a ‘smaller’, less complex version of himself?

Contextualising the letters, Forbes begins by surveying the kinds of treatment scholars have accorded Gandhi’s relationship with women. Early works in women’s history tended to paint him as an “imperfect supporter of women”, but a supporter who nonetheless eased their passage from the private into the public arena. There is no getting away from the fact that there is a vein of essentialism that runs through Gandhi’s casting of the category ‘woman’, obvious each time he countenances, for example ‘their’ “greater capacity for suffering”. More, his reduction of sexuality to a single story (and one with singularly disastrous consequences at that), is even more glaringly marked for someone who otherwise transcends the trap of binaries and absolutes, almost instinctively.

Gandhi’s own sexuality and experiments with brahmacharya have been much discussed, in isolation from his politics, spirituality and other questing, and often in less than scholarly ways. It is also in this ‘general’ vein that writers like Martin Green and Girja Kumar have attempted to outline what they hold is the erotic subtext of Gandhi’s relationship with Sarala Devi (with Kumar’s version turning their story into a grossly stereotypical, comically Bollywoodesque cautionary tale about the ‘great man’ almost brought to perdition by an unworthy woman).

It should be obvious that these accounts, reveal more about their authors than they do about Gandhi and Sarala Devi. They show us the bounds of their understanding or imagination of what a relationship between men and women, predicated on true companionship, can be. Simultaneously, they fail to recognise just how rare such relationships were in the 19th-and the early 20th-century- India.

Additionally, none of these writers had access to the letters in question. Thanks to Forbes, we do. And in them we see, especially in the early letters of April 1920, just how much experiencing this level of compatibility meant to Gandhi’s scheme of things. So much so, that instead of feeling everything that was coming up for him, he sought immediately to sublimate his emotions, channelling them into musing on ‘fitness’ for higher, wider, ever more public, service.

Is it in correcting for the unjustified and ridiculous excesses and distortions of Kumar and Green and others of their ilk that Forbes underplays the power of this dynamic? Why should Gandhi not have felt what might be thought of as attraction – mental, spiritual and otherwise – without it becoming the ‘single story’ of this, or any, relationship? Why may he not have simultaneously marvelled at Sarala Devi’s intelligence, rejoiced in her conversation, and recognised her fitness for political work?

The men who have written about this relationship have done so without acknowledging how formidable an interlocutor Sarala Devi was. Forbes points out that even some in Gandhi’s entourage “thought they had become too close and that Gandhi spoiled her and paid too much attention to her opinions.” Might this too be more indicative about the entourage than the relationship they saw as problematic? The text stops short of spelling this out.

On reflection, might not the attitude of Gandhi’s followers be read as yet another example of how Gandhi has been reduced by so-called Gandhians; force-fitted, into a ‘smaller’, less complex version of himself? He contained multitudes, including aspects which discomfited people around him in the many ways they troubled normativity. Think about the fracas caused at one point by Gandhi’s proposal that eggs be made available at the ashram for a convalescing Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan. The ashramites, of course, thought it was too ‘non-Gandhian’ an idea to countenance. I cite this to illustrate that some members of his cohort, creatures of their time as they were, could be small-minded on occasion. Plagued by the literal, they tended to flounder with metaphor.

***

Gandhi’s letters addressed Sarala Devi alternately as ‘sister’, ‘Sarala’, and, for a time (when he began to realise that she was perhaps too wilful to be moulded into the embodiment of ‘Shakti’ he thought she was or wished her to become), ‘my dear girl’, which reads as condescending, if not infantilising. The letters almost always inquired after her husband and supplied her with news about her son (who was sent to study at the Sabarmati Ashram, where Gandhi was keen both Sarala Devi and her husband would join them). They were inflected with questions about readiness to serve: true both of Gandhi as well as Sarala Devi, even when (especially when?) these questions come up on the back of statements Gandhi made about missing having her by his side in the fight, or that she was the first person his mind goes to upon waking up in the morning.

Sarala Devi was hugely impressive. Forbes lingers on each period, giving it the treatment it deserves in highlighting the making of a subjectivity as rich as it was, in some ways, radical. This allows us to see clearly the woman who so moved Gandhi.

The April 1920 letters especially exulted in this new ‘connection’. Gandhi seemed to see this relationship as a “blessing to us and to others,” (2024, 76) in the way it modelled another way in which men and women could relate to each other as people: companions, compatriots, and co-workers. What these letters were also full of was constant complaints about Gandhi’s physical health: headaches which laid him low, leg pain that disallowed walking –so vital to his understanding of ‘wellness’ – and weakness that lingered and did not let him function at capacity.

The book does not explore this theme. It does not, for instance, locate this Gandhi as the convalescent who was still, in some ways, making his way back from what he described as the “worst” illness of his life, which lingered months on end in 1918, and a while after. Dalton and Weber (2020) describe this ‘mystery’ illness as a full-blown physical and mental nervous breakdown. Care, we know, was central to Gandhi’s praxis, but what did it mean to both lavish and receive it? Was he as capable in 1920 of receiving care as he was of giving it?

This breakdown, precipitated by the cognitive dissonance born out of his attempt “to enlist peasants for the British war effort,” to do which “he travelled and pleaded endlessly,” on a minimal diet meant that “things were coming apart for him physically and mentally. Exhausted, he not only fell physically ill, but also sank into a period of spiritual lassitude and moral bafflement” (2020, 7). Is this also why the cohort around him was alert and concerned when he began to complain repeatedly of ailments again in 1920, around the same time he was invested in creating a tall nationalist leader out of Sarala Devi? These questions remain unanswered.

***

Lost Letters does both its protagonists the courtesy of turning the searchlight upon them in equal measure. Forbes shows us Sarala Devi as the child who grew up with “a distant and aloof mother”; as the young woman who, both because she came from deep generational privilege (she was Rabindranath Tagore’s niece, lest we forget) as well as because she proved such an avid learner, received no “training in household tasks,” unlike many others in her own family who were schooled into gendered work young; as the activist-reformer who started a school for young women with her sister in the early 1880s; as the young woman who insisted on leaving the “cage” of her home and earning her “living independently as my brother did,” (an aside: Sarala Devi made her way to Mysore to teach at a girl’s school there, but had to leave shortly after, because a man broke into her apartment one night “as a reprimand to adventurous young women” everywhere); as the political thinker who, in the early 1900s, believed armed struggle was crucial to Indian independence; as the woman who married – into another deeply political family – at the age of 33, which was late by the standards of her time, only to keep working on the nationalist cause alongside her husband in her new home in Punjab; as the spiritual seeker who wanted to make for the Himalayas in 1920, even while Gandhi was trying to ‘shape’ her into one of the primary leaders of the emerging nationalist movement.

Did Gandhi fully realise that there was a person on the other side of his letters – one he could not mould as he deemed fit? ... Were they co-scientists, or did he reduce this other into a lab rat?

As should be obvious, Sarala Devi was hugely impressive. Forbes lingers on each period, giving it the treatment it deserves in highlighting the making of a subjectivity as rich as it was, in some ways, radical. This allows us to see clearly the woman who so moved Gandhi.

Their correspondence makes clear that Gandhi’s views on the centrality of khadi to his wider project cannot but have become clearer to view in conversation with, among others, Sarala Devi. This theme certainly needs more study, but in the absence of her letters to Gandhi, one struggles to see how it can be done. It feels pertinent to note that Gandhi’s decision to give up ‘formal’ dress, opting instead for minimal clothing, exclusively in khadi, was also made around this period. While “discussing his plans to travel throughout India” to promote khadi, Gandhi said he would “take Sarala with him as she ‘better understood his swadeshi principles than his wife’,” and arguably, many others of his entourage. However, he was not content with what he saw as Sarala Devi’s commitment to consuming swadeshi – he realised this was meaningless without also making/producing swadeshi.

The book could have, but does not, discuss for instance, the many ways in which it appears that one source of Gandhi’s own notions of the spaces between swadeshi and swaraj show up in the figure of Sarala Devi. She championed khadi, “praising it as comfortable and artistic,” and helped elevate it to the primary visual marker of the nationalist movement that it would go on to become, but did not produce it herself until later, when she and Gandhi were no longer in constant conversation. Swadeshi might well be built upon the labour of others, but for it to translate into swaraj, the work must be done ourselves. Ultimately, the letters seem to suggest that this is one of the chasms that open between Gandhi and Sarala Devi.

Forbes writes about this relationship as one of Gandhi’s “extremely interesting ‘experiments’ – working closely with and mentoring a woman he imagined could become an important national leader” (2024, 5). However, shorn of her responses to Gandhi, and given what we know she had expressed a desire to do – retire and live in the mountains – was this what she wanted? We are left uncertain.

Did Gandhi fully realise that there was a person on the other side of his letters – one he could not mould as he deemed fit? Did he see her or only that which he thought she could become? Were they co-scientists, or did he reduce this other into a lab rat?

We know this changed two decades later, with Manu, but that was not the same Gandhi, and Sarala Devi was not Manu. It is obvious that Gandhi was, in 1920, taken with an interlocutor he found as engaging as she was challenging. Before he tried to mould her into the nationalist leader he wished her to become, she was someone who came into his orbit fully formed: this Chaudhurani was not of his making.

Harmony is an Associate Professor of Cultural Studies at MICA, and the author of ‘Walking from Dandi: In Search of Vikas’ (OUP, 2022).