The female labour force participation rate of women (LFPR) in India is one of the lowest in the world, and falling. It is even lower than that in neighbouring countries. The reasons for this have been analysed extensively (Mehrotra and Parida 2017; Mehrotra and Sinha 2017; among others).

Jose (2021) pointed out that educated women find it difficult to find employment. This has much to do with employment growth remaining low generally, so women tend to fall behind. From the higher secondary level onwards, the unemployment rate of women is at least 50% or more, twice the corresponding ratio for men. Jose even suggests that the figures indicate that any advancement of women’s schooling is likely to be accompanied by a higher incidence of unemployment among them, unless, of course, more jobs are created.

However, here we ask: could there also be issues with the way the National Statistical Office (NSO) measures female LFPR?

For more than 30 years, key economic indicators have been based on a framework adopted at the 13th International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS) in 1982. Within this framework, individuals were employed, unemployed, or economically inactive. With time, it became clear that these categories, and their accompanying definitions, were insufficient to fully capture how individuals — women in particular — contributed to the economy or the well-being of their households.

At the 19th ICLS in 2013, new, more gender-sensitive standards were adopted with refined definitions and additional categories. These standards were built on countries’ experiences and were to support international harmonisation and implementation of best practices. As these changes were introduced, a discussion arose on how this would affect data collection and impact women.

The real question is whether or not the low female labour force participation rate and the current method of estimating women’s work are credible.

India’s Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), started in 2017–18, has avoided adopting the international standard of the 19th ICLS definitions and questionnaire, and pretty much stuck to the older methodology. This is a problem because the Indian economy and labour market have undergone massive changes since the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) adopted its questionnaire, which in the Employment Unemployment Survey (EUS) and PLFS has remained pretty much the same. The NSSO continues to avoid making changes. Meanwhile, India’s labour force statistics seem to be understating women’s work, as reported in the National Sample Survey (NSS) data.

The NSS Time Use Survey (TUS) 2019 for India tells us that more than 90% of Indian women participated in unpaid domestic work at home in 2019 compared to 27% of men. On the other hand, only 22% of women participated in employment and related activities compared to 71% of men. This distribution of unpaid domestic work is a major barrier to women “officially” participating in the labour force (Deshpande 2020).

Domestic work is separable from the worker and can be done by others. Therefore, unpaid domestic work should be redistributed between men and women. The 'triple R' approach (recognition, reduction, and redistribution) attempts to integrate unpaid work into the mainstream economy by reducing it and by reorganising it between paid and unpaid work.

For decades, there have been question marks over the way the NSSO measures women’s labour force participation.

The real question is whether or not the low female LFPR and the current method of estimating women’s work are credible. For decades, there have been question marks over the way the NSSO measures women’s LFP (Hirway 2015, 2017, 2018). I attempt here to reassess whether we need to change or adjust definitions to bring them more in line with the Indian System of National Accounts (ISNA) and the UN System of National Accounts (UNSNA), or in line with international labour force statistics standards. Or do we just need to train enumerators better? Or are both needed to bring the estimates of India’s female LFPR more in line with reality, as well as in line with international measurement standards and norms? Consistent with this approach, some of us who are members of the Standing Committee on Economic Statistics of the NSO have been making a case to the organisation that a pilot revised schedule/questionnaire of the PLFS must be carried out as soon as possible.

Conceptualising work in the household

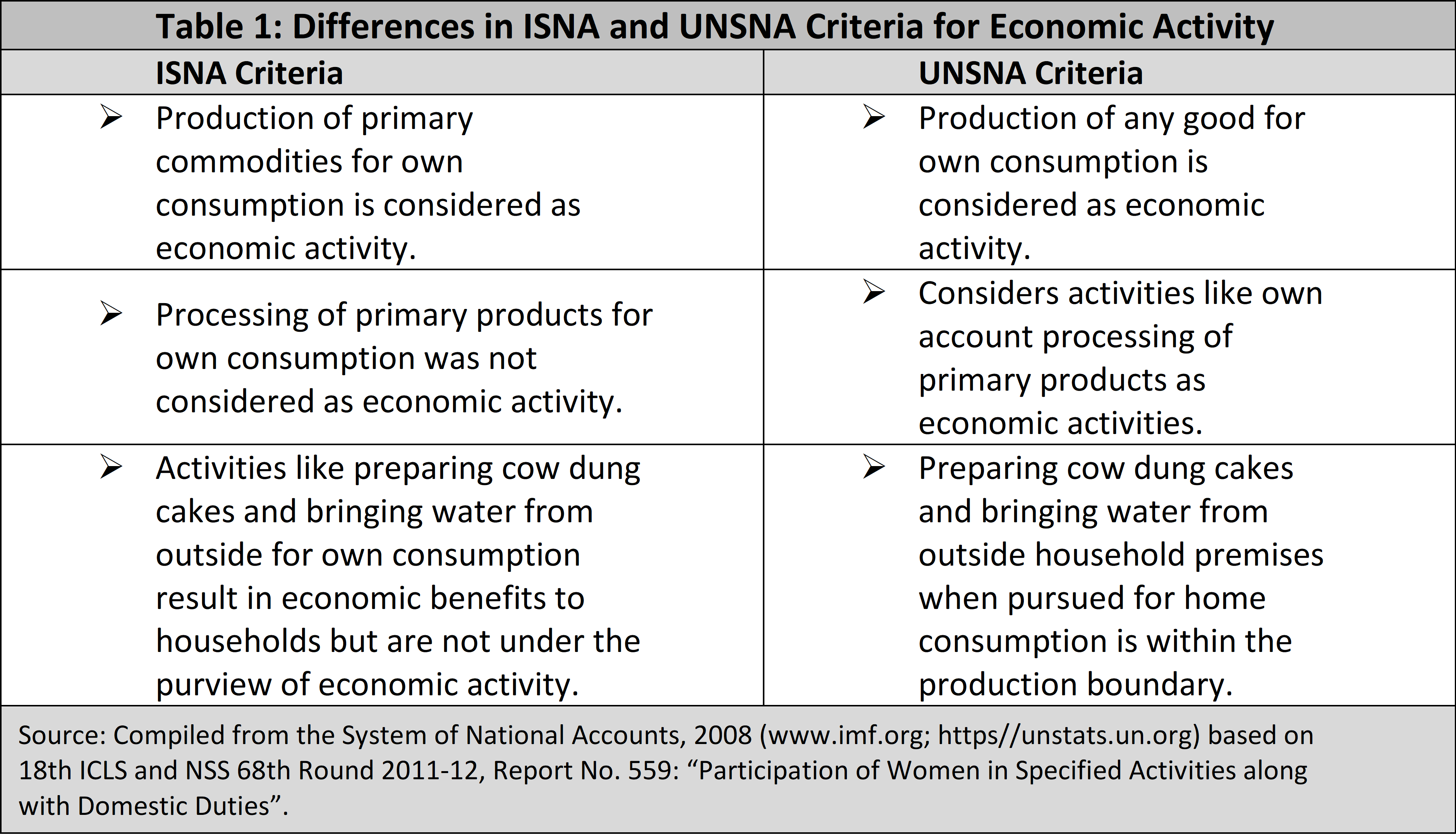

There are differences in the criteria of the ISNA and the UNSNA. One of the reasons why women’s work is being under-counted is that the division between economic activity and non-economic activity is different in the Indian and UN systems, as Table 1 shows.

Thus, if the NSO was following the UNSNA classification, women’s LFPR in India would be much higher than is currently the case. So an issue is that the Indian SNA is following its own definitions.

India is not alone. A number of countries that still use the old standards pick and choose which activity to include in employment. They do not include all own-use activities. This was one of the reasons the 19th ICLS was introduced — to bring consistency. Although these activities were taken out of employment, the 19th ICLS framework allows them to be measured as a different form of work. This helps us to know more about how they interact with income-generating employment.

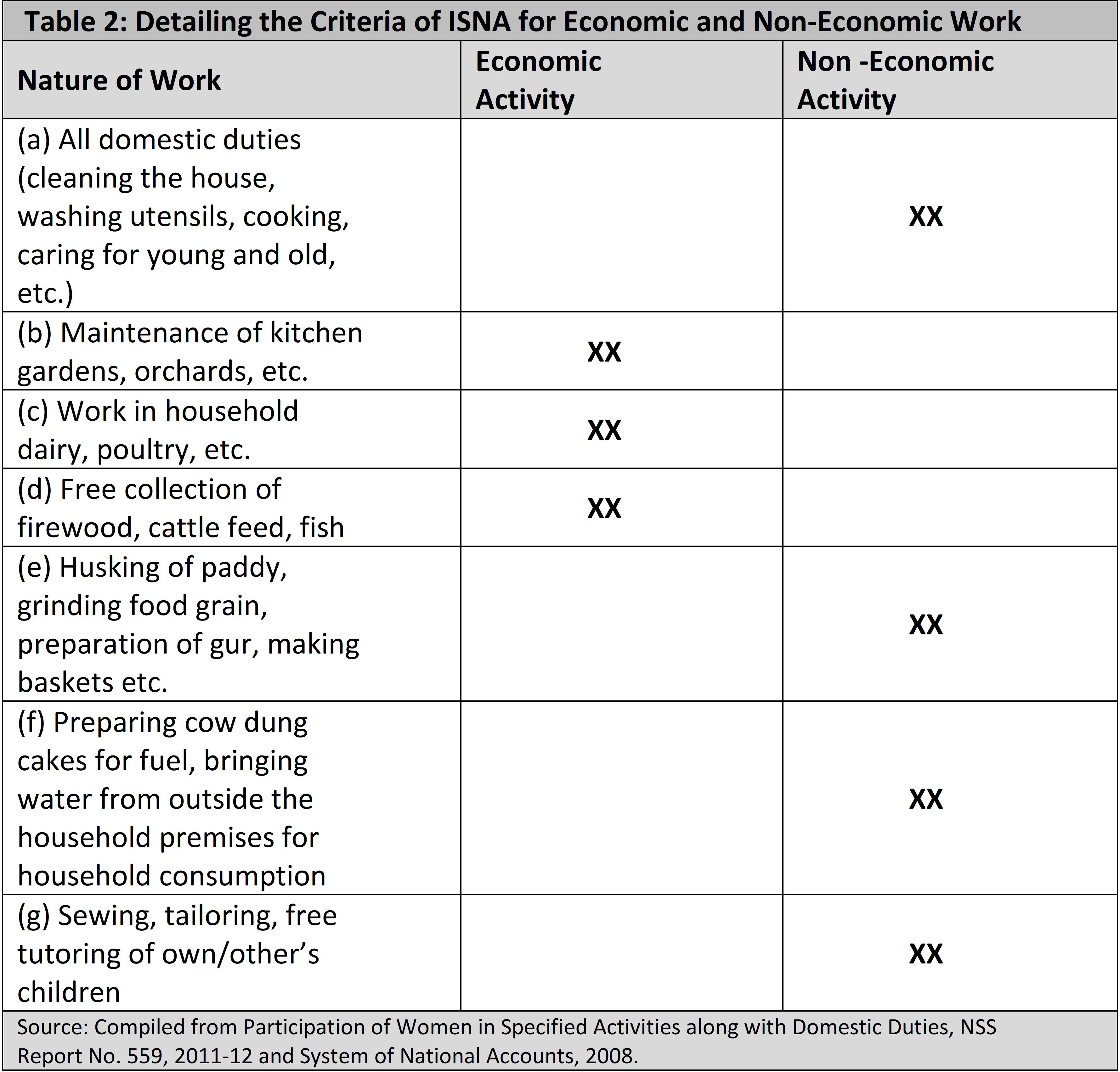

Table 2 shows that in the conceptual design of the ISNA, specified activities carried out by women within the household can be classified into two broad types — economic and non-economic activities.

The UNSNA records activities such as processing of primary products for own consumption as economic activity (SNA 2008). If the ISNA were to be consistent with the UNSNA, that would go some way towards correcting the measurement of female WPR. Such economic activity creates possible measurement errors while calculating the workforce participation of females in agriculture.

The production boundary as defined by the UNSNA is much broader than the ISNA. The ISNA uses a narrower range of economic activity [categories (b), (c) and (d) in Table 2] and excludes various kinds of activities [categories (a), (e), (f) and (g)] from the domain of economic engagement. This is important when calculating female workforce participation in agriculture.

The NSS questionnaire might not be capturing (b), (c), and (d) adequately.

Yet another issue is informal employment. By definition, informal employment, especially of the self-employed or casual variety, which accounts for three-fourths of India’s workforce, is often intermittent, scattered, temporary, short term, or unstable. Hence it is frequently not reported accurately in the labour force survey/PLFS. This is why the tools (that is, the questionnaire) to capture this should be revisited and one that can capture all sorts of activities designed.

The ILO has shown that a careful questionnaire design is needed to make sure both the perceived and the actual situations are captured.

Again, women frequently view work as a part of household work and under-report it. Also, the earlier surveys/PLFS were not equipped to collect data on multiple jobs performed by people, especially when the work was performed along with other activities. Neither the TUS nor the PLFS have managed to capture this complexity of women’s work, with the end result that women’s work continues to be underestimated.

Significance of the 19th ICLS

Individuals who have unpaid support roles in a family business, but do not have the authority to make decisions in that business, are classified as contributing family workers. Women are more likely than men to fall into this category. The International Labor Organization’s (ILO) pilot studies (in 2020) globally (though not in India) in pursuance of 19th ICLS (2013) show that this is partly a result of actual differences in roles and partly a result of women’s perceptions that they play a less important role despite their actual roles being more similar. The ILO has shown that a careful questionnaire design is needed to make sure both the perceived and the actual situations are captured.

This is of relevance to India and the issue we are discussing here. While many young men and women report themselves as falling into this category, as age increases, men are less likely to remain in this role than women. In the oldest cohort, people aged 65 or older, women are four times more likely than men to report they are contributing family workers.

Thanks to the 19th ICLS, by shifting from only measuring employment to measuring all work, it is evident that we previously underestimated the working time of all individuals, but much more so of women. From the pilot studies, the ILO shows that the previous approach showed employed women working an average of nine hours fewer than men per week, while the new one shows that women work on average 10 hours more than men per week when different forms of work are measured. While men spend 70% of their working hours in employment, for women it only accounts for about 50% of their working time. However, women spend nearly three times as many hours as men doing unpaid work for their families (ILO 2020).

The way forward

The NSO needs to consider the following.

● International standards in statistics are what allow us to have global data. Statistical standards are arrived at by years of deliberation among the world’s statisticians. This article recognises the 19th ICLS framework on work statistics and presents data that support an objective of the new framework, which is better identification of all forms of work, paid and unpaid. India’s conceptual framework for employment statistics provides support for the new framework for work statistics. A good approach for the NSO and India would be to accept the 19th ICLS and build on the new framework of work statistics to improve the measurement of women’s work.

● The NSO needs to examine the consistency between India’s SNA and the UNSNA, and align the NSO’s surveys and estimates of labour force participation in accordance with international practice. In particular, the definition of what is and is not an “economic activity” needs another thorough review. 1However, the change in the new ICLS concept of employment to include only work that is done for pay or profit creates a discontinuity between it and the SNA. The SNA is currently undergoing revision and it may well result in alignment with the new standard of employment.

● Conceptual modifications can be adopted in the present PLFS by adding more categories in such a way that one can also get estimates comparable to the past EUS. This is the easy part. A worry is about the modifications that would be required in the methodology of data collection. The NSSO should possibly look at the TUS more carefully to study the distribution of various SNA activities in a day for women, along with the time taken. Unfortunately, the TUS has clubbed the time to half hour intervals and not differentiated activities during this interval. The question is how much time should be considered significant to be categorised as work by whatever definition used—valuation of input time and corresponding production of services. 2The ILO is now testing how to implement the criteria that household production should mainly be for sale to be considered as employment. One doubts that time use surveys can tell us much about this.

● There is a possibility that the sample in urban areas may be missing out on significant parts of the population. India’s female LFPR is much lower in urban than in rural areas—the EUS and PLFS have both reported much lower female LFPR. In contrast, more locally based urban samples (for example, conducted by the Self-Employed Women’s Association) have shown much higher female LFPR than the EUS/PLFS. Thus there may be another design issue that needs to be addressed, which is specific to the undercounting of women’s employment in urban areas. We know that the more educated a labour force, the better the likelihood of a high LFPR, especially of women. Similarly, the more urban a workforce, the higher the LFPR of women. However, India’s LFPR trends for women do not show a rise until 2011-12, though that has been changing since 2017-18.

● This effort at the conceptual level will need to be supplemented with more training of enumerators in the PLFS. Or else, all efforts at conceptual changes could prove infructuous. The PLFS is being conducted by trained but contractual investigators, while the regular permanent field staff is involved in other surveys. This needs to change. Labour force surveys are a complex exercise, and the NSO’s most experienced staff should be at the cutting edge of this work.

On top of the Usual Principal plus Subsidiary Status way of measuring employment, the schedule in its current form will not capture agricultural and other unpaid work that women do. The usual activity is much less relevant with a continuous survey and it influences how field workers or respondents report the Current Weekly Status, because Usual Principal and Subsidiary Status are asked before the CWS. That is why at times we do not see much difference between the two estimates.

Acknowledgements: I wish to thank, P.C. Mohanan (formerly of NSO), Renana Jhabvala (SEWA), Indira Hirway, Hema Vishwanathan, Joann Vanek (WIEGO), and G. Raveendran (formerly of NSO) for comments on an earlier draft. I also wish to acknowledge the support of Sangeeta Thakur, PhD scholar at the Centre for Informal Sector and Labour Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, for her useful inputs. The usual disclaimers apply.

Santosh Mehrotra is with the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi.