Marriage has long held immense significance in Indian society, particularly for women, impacting various aspects of their lives, such as social standing, economic opportunities, and overall well-being. In contrast, widowhood – the civil status following the death of a spouse – has traditionally been viewed as challenging and especially detrimental for women in this country (Chakravarti 1998).

Widowhood is almost visibly absent in many cases for men, but for women while extreme practices like sati were abolished long ago, the customs and norms associated with widowed women still operate in a subtle way within Indian households.. Widowed women continue to endure harsh societal norms of 'grieving'. In many cases, wives were held accountable for their husbands’ deaths and subjected to verbal abuse (Mathur 2023).

Such norms result in discrimination and impose restrictions on widows’ clothing choices, movement capabilities, access to food, and working prospects. Further, widow remarriage remains highly stigmatised in India, and this stigma is particularly pronounced for young widowed women. Evidence also stresses the profound economic shocks and health-related challenges that widows confront following the loss of their spouse. Thus, widowhood in India has become a widely recognised identity for women, symbolising their exposure to mistreatment and categorisation as a vulnerable group (Agarwal et al. 2021).

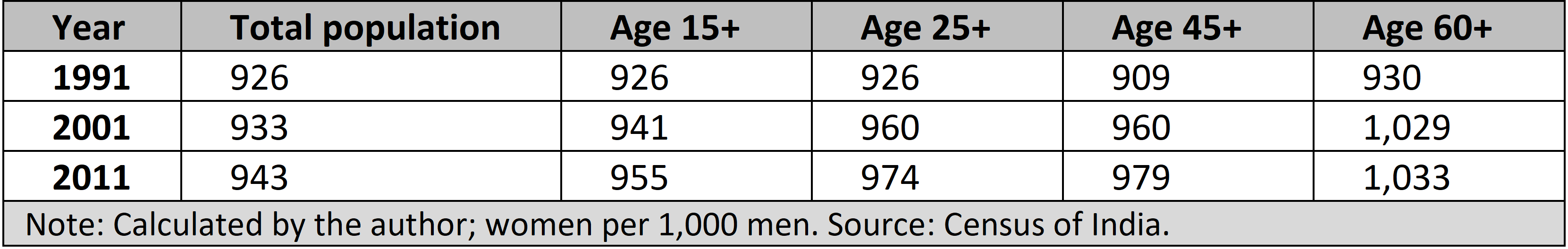

Even from a demographical perspective, there is significant gender disparity in the widowed population in India. Table 1 shows the sex ratio of India at selected ages for the overall population from the censuses of 1991, 2001, and 2011. The number of women was lower than men in the 15+, 25+, and 45+ year age groups in the last three censuses, indicating that men outnumbered women. Only in the 60+ age group did women outnumber men in 2001 and 2011. However, a different viewpoint emerges when widowhood and gender factors are considered.

Table 1: Sex Ratio of Selected Age Groups in India, 1991, 2001, and 2011

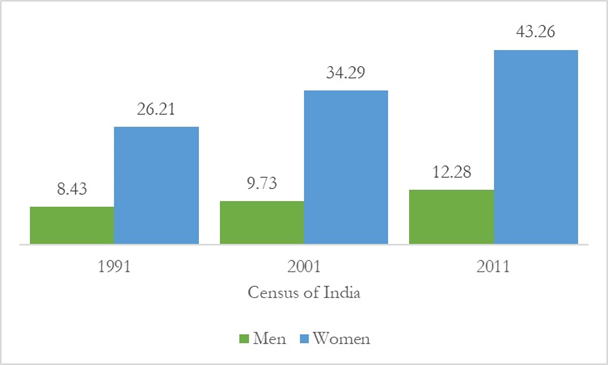

According to the recently released Loomba report (2022), there are a staggering 245 million widowed women across the globe, out of which India alone accounts for approximately 17.3%. As per data from India’s last census conducted in 2011, there were almost 43 million widowed women compared to 12 million widowed men in the country’s population (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of Widowed Population by Gender in India, 1991, 2001, 2011 (in millions)

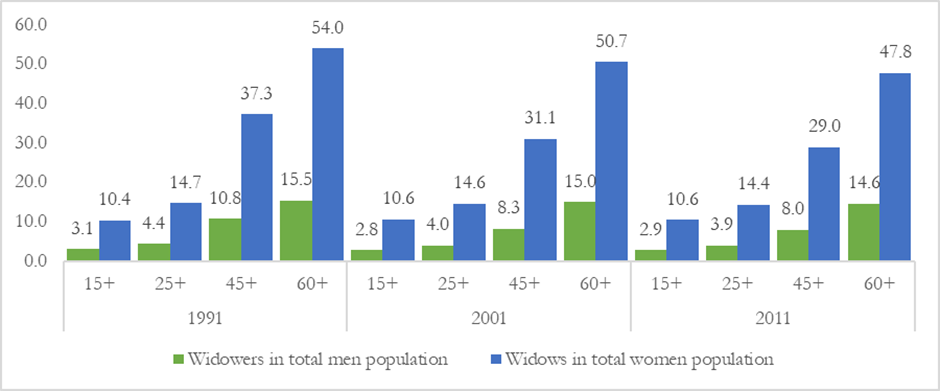

Further, the proportion of the widowed in the total population across different age categories (Figure 2) indicates that women comprise a higher share of the widowed than men. As per the last census in 2011, 29% and 48% of the women aged 45 and 60 years and above were widows, respectively. This number is significantly higher than that of men, with 8% and 15% of men aged 45 years and 60 years and above being widowed in 2011. This highlights the feminisation of widowhood in Indian demography (IIPS &UNFPA India 2023).

Figure 2: Percentage of Married and Widowed By Gender in Selected Age Groups in India, 1991, 2001, and 2011

Yet, given the well-documented history of prejudice against widows and that widows, particularly older widows, account for a sizeable portion of India’s population, an important question arises. Should the focus solely be on highlighting the issues that widowed women face, including economic, social, and health-related, in modern India? Or should a nuanced gender perspective be considered? It is also crucial to acknowledge that widowed men struggle to cope with household chores after the death of their wives and the lack of care previously received from their wives directly impacts their overall well-being. Hence, it is imperative to highlight the impact of gender as a pivotal moderator shaping the different experiences of the widowed population in India.

Having said that, we can comprehend the depth of suffering and vulnerability endured by the widowed population if we make a comparison between the widowed and the married population as a whole. Therefore, two critical questions appear. Is the Indian widowed population currently more vulnerable in various domains of life than the married population? In which domains of life do the experiences of widowhood differ by gender?

Economic vulnerability and food insecurity

Economic and food insecurity are two of the most basic aspects associated with widowhood and the combination of ageing and gender adds an additional dimension.

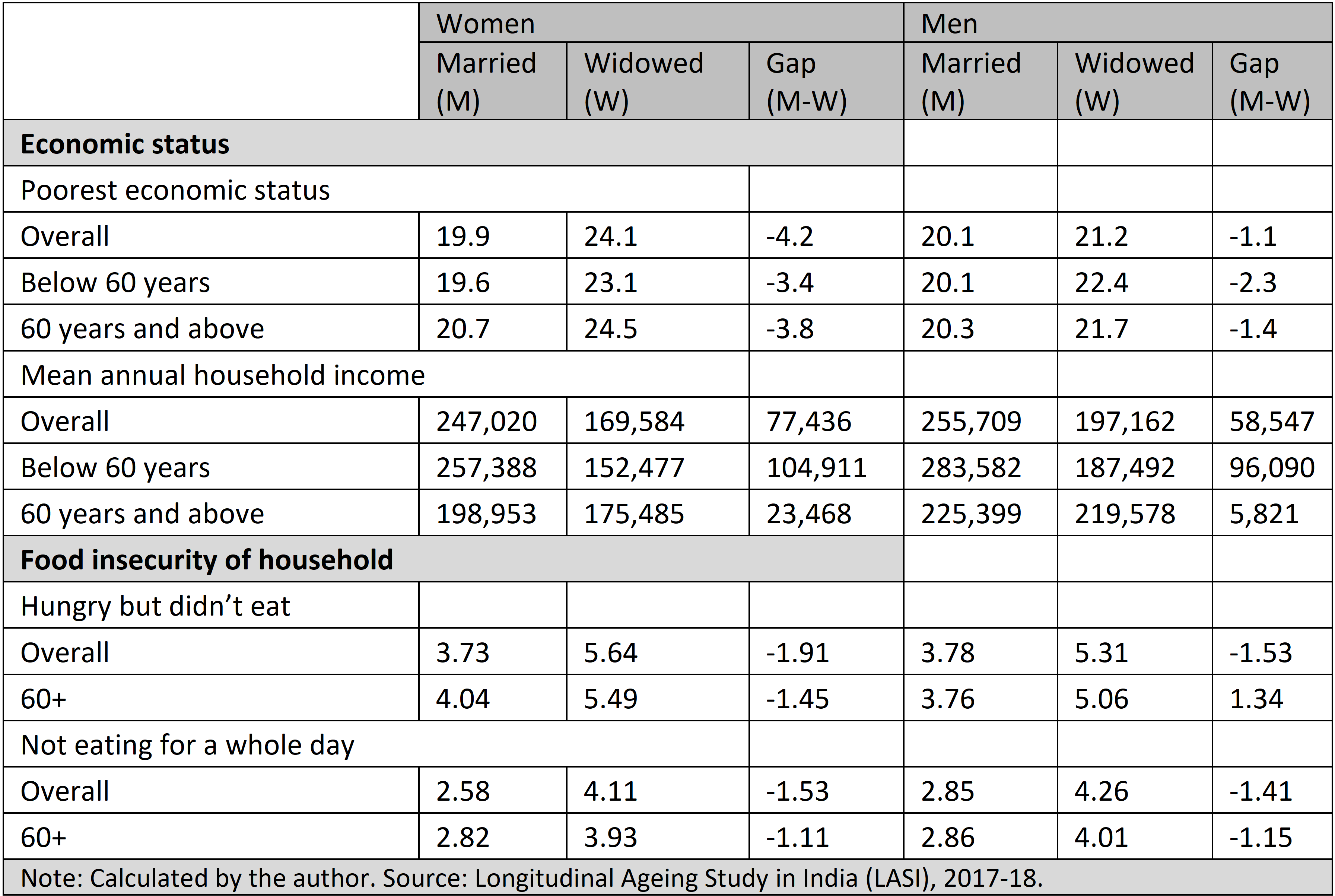

Table 2: Economic Status and Food Insecurity of Household by Marital Status, Gender, and Age of the Head, 2017-18

It is generally accepted that the end of marriage via the death of the spouse results in greater economic shock for women than men. Therefore, it is crucial to evaluate the recent economic aspects of the widowed population by gender to comprehend the contemporary Indian landscape. In Table 2, the wealth index of households has been considered to understand the impact of the marital status of the head of the household on overall economic status. Basically, the wealth index is determined by assessing the household’s possession of specific assets.

According to the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) conducted in 2017–18, the data reveals that 23% of overall widowed adults who were also the head of the household belonged to the poorest wealth position in India, compared to 19% of married counterparts. The number indicates that the impact of widowhood on the poorest wealth status of households was more prominent amongst women than men across age groups.

On food security, 6% of Indian adults reported missing meals or cutting back on the amount of food they ate because there was not enough food in their household.

Similarly, the Longitudinal Ageing Study data indicated that the mean household annual income for an overall widow-headed household was Rs 175,081, which was lower than that of a married-headed household, which was Rs 251,232 (Table 2). Further, the gender and age axis highlighted that widowhood effects on total household income were more in women-headed households than men-headed ones. It is more notable in later age. For instance, the marital gap (difference between married and widowed groups) in the mean total household annual income between married and widowed women-headed households for 60 years and above was Rs 23,468, which was significantly higher than for men.

On food security, 6% of Indian adults reported missing meals or cutting back on the amount of food they ate because there was not enough food in their household (IIPS 2020). Although this number may seem minimal, food insecurity has nutritional and health-related consequences, particularly amongst older adults (IIPS & UNFPA India 2023). In this situation, it is expected that the proportion of widowed women would be more when it comes to food insecurity than widowed men (Table 2). Conversely, the Longitudinal Ageing Study data indicates that widowed women and men had almost similar exposure to food insecurity. For instance, the marital gap for being hungry but not eating, or not being able to eat for a whole day, is almost the same for women and men.

These findings suggest that widowhood is not only linked with higher economic vulnerability for women but that it also impacts widows’ food insecurity more than that of married women. In addition, men are not completely immune from widowhood. After the deaths of their wives, widowed men experience food-related insecurity.

Experience of abuse in the household

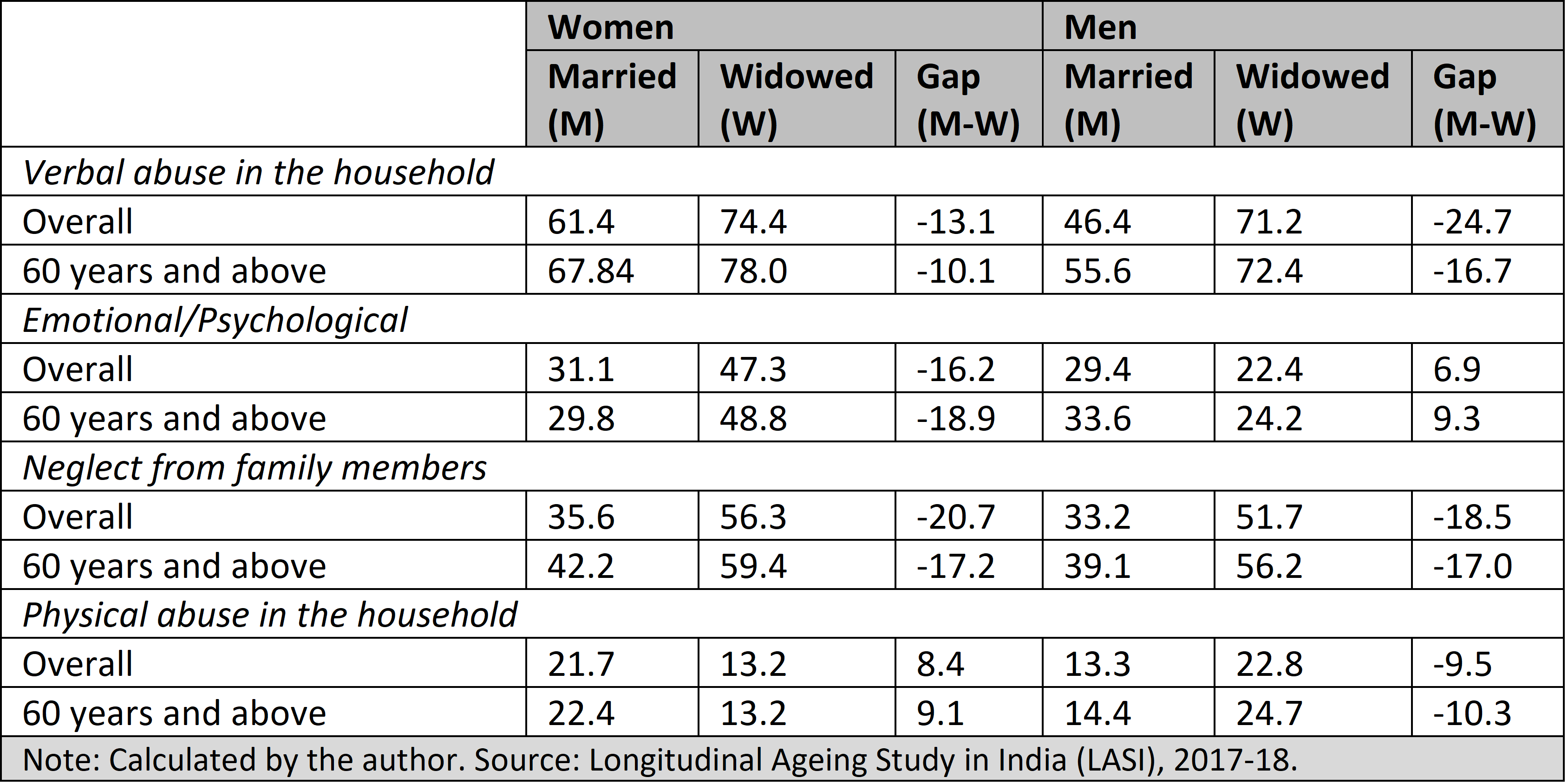

With the death of a spouse, women experience economic and social shocks, while men find themselves burdened with household chores while receiving less care. These vulnerabilities, in many cases, lead to various forms of abuse, including physical, verbal, and emotional or psychological abuse, and neglect by family members. The current evidence indicates that the marital gap for emotional or psychological abuse, as well as neglect, from family members is higher for women compared to men. On the other hand, the marital gap for verbal and physical abuse from family members is higher for men than women. However, the Longitudinal Ageing Study reveals an intriguing observation: there is a notable gendered contrast in the forms of abuse experienced by widowed and married individuals in Indian households (Table 3).

Table 3: Experience of Abuse of Married and Widowed Population in India by Gender and Age, 2017-18

For example, widowed women experienced a higher degree of emotional and psychological mistreatment in the household compared to married women, but the situation was the opposite for men. Married men experience a higher degree of emotional and psychological abuse in their households compared to men who have lost their spouses.

On the other hand, regardless of age, married women had a higher prevalence of physical abuse inside the home compared to widowed women. Although the marital difference in physical abuse for women indicates that the physical violence against women may come mainly from the spouse, this finding based on the Longitudinal Ageing Study needs further detailed discussion. Amongst men, there is a shift in dynamics with widowers experiencing more physical abuse to married men.

Health-related vulnerability

The widowed population in India faces significant challenges, including economic vulnerability, abusive behaviour from family members, and food shortages, all of which may adversely affect their health. Academic literature consistently demonstrates that widowed individuals, both men and women, exhibit a heightened risk of developing various morbidities and mental health issues, engaging in unhealthy behaviours, and experiencing an increased risk of early mortality compared to their married counterparts. This phenomenon is commonly referred to as the widowhood effect.

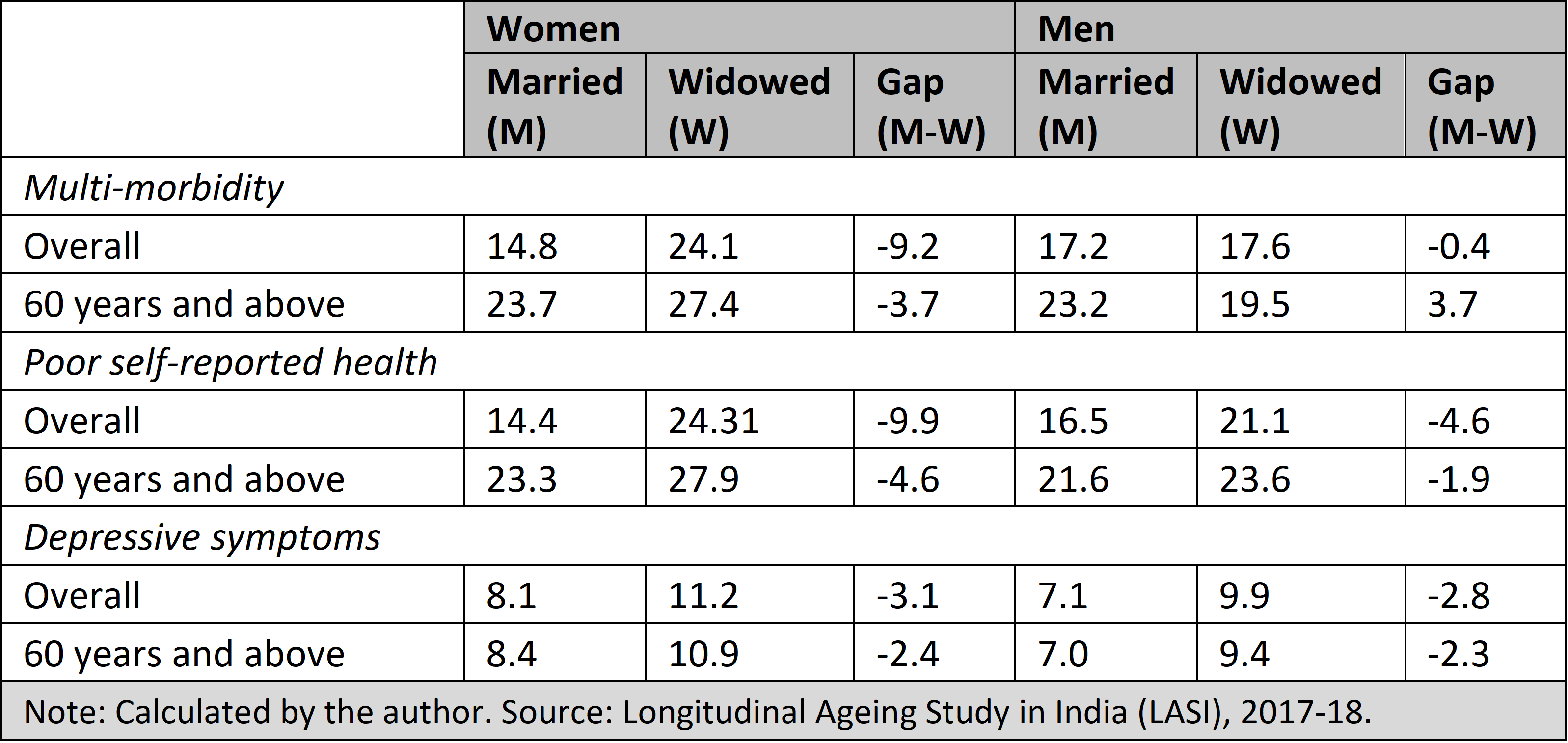

To comprehensively understand the impact of widowhood on health, key indicators such as multi-morbidity for physical health status, self-reported health status on the general perception of individual health, depressive symptoms (Table 4), and mortality risk have been considered (Figure 2).

Table 4: Health Status among Married and Widowed Population by Gender and Age in India, 2017-18

The recent numbers suggest that multi-morbidity, a condition where an individual is reported to have two or more chronic physical health problems is higher amongst the widowed (22.85%) compared to the married (16.11%) (Longitudinal Ageing Study 2020). By the gender dimension, it is again evident that women have more chronic physical problems because of widowhood than men do.

Looking at self-reported health status, an indicator used to measure the perception of a person’s health in general, indicates that widowhood affects poor self-reported health more amongst women than men. For instance, the marital gap in self-reported health is significantly higher amongst women than men.

Coming to mental health, the Indian widowed population is vulnerable to higher depression than married Indians are. Almost 11% of the overall widowed population in India reported having depressive symptoms against 7% of all married individuals. However, there is not much difference in the marital gap in mental health between men and women.

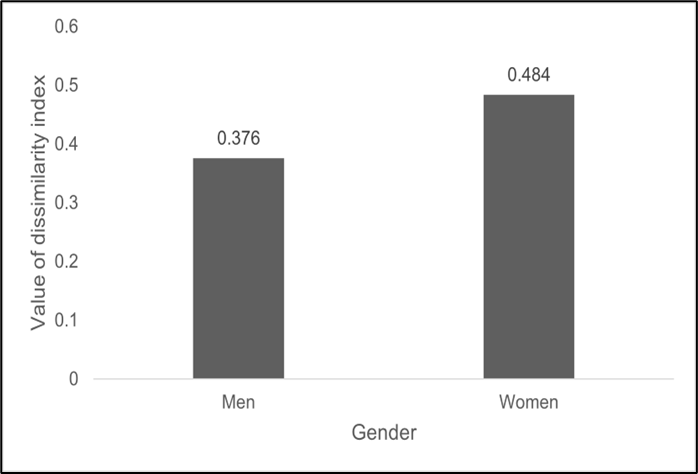

Also, an attempt has been made to measure the magnitude of dissimilarity in the mortality between married and widowed Indians by gender using the dissimilarity index (DI). The dissimilarity index value ranges from 0 to 100, where 0 indicates no dissimilarity and 100 indicates full dissimilarity in a specific group. The results suggest that the dissimilarity index value was 48.4% for women and 37.6% for men (Figure 3). These numbers indicate that there is higher dissimilarity in mortality amongst women, or that widowhood possibly causes greater dissimilarity in mortality for women than for men in India.

Figure 3: Dissimilarity in Mortality between Married and Widowed Individuals by Gender in India, 2004–05 to 2011–12

Discussion

The widowed population in India is indeed more vulnerable in different domains of life than the married population. Further, it is possible to assert, based on secondary data, that widowhood-related vulnerability in many aspects of life is more prominent for women, though Indian men also experience vulnerability in life due to widowhood.

The vulnerability of the widowed population in India follows some expected patterns by gender, but some of the findings are intriguing.

First, considering the economic vulnerability of the widowed population over married people, the financial shocks are more for women than men. There is a difference in wealth accumulation as well as the total household annual income by marital status where widowed women lead households are more likely to belong to the poorest wealth status and have a lower annual household income. However, a similar pattern can be seen for men, but the marital gaps are comparatively lower for men than women. These findings are very much indicative that widowhood brings greater economic volatility for women than men even in contemporary India.

Second, given the increased economic vulnerability experienced by women widows, it is reasonable to anticipate that they may face greater levels of food insecurity than men. However, men are also susceptible to experiencing food insecurity as a result of widowhood. For example, the married and widowed gap that experienced hunger and went without food for a whole day owing to a lack of food in the household was about equal for men and women, with the widowed experiencing higher food-related insecurity. These findings certainly indicate that financial insecurity might cause increased food-related insecurity for widowed women. But for men, higher food insecurity highlights the inability to cope within a household setting for widowed men.

Third, an intriguing observation shows that there is a sizeable gender difference in the types of abuse that the widowed population in Indian households experience compared to those who are married. Being widowed, women are more likely to be subjected to emotional and psychological maltreatment than married women. It may be because of patrilocality norms in India, where women continue to live in their in-law’s houses even after the death of their husbands and are dependent on them for their economic and social support.

Widowed men might become victims of physical abuse possibly if they are dependent on others for care, particularly at later ages. On the other hand, married women had a greater incidence of suffering from physical abuse compared to married women. However, we have to be very careful when interpreting this finding based on Longitudinal Ageing Study data, particularly for women. It may seem that the physical abuse that women experience is intimate partner violence (Firdaush and Das 2023), particularly from their husbands, and widows who have lost their husbands may experience less abuse. However, there may be more complex mechanisms behind this result. Therefore, we need more data and detailed studies focusing on forms of physical abuse against women as well as men through the lens of marital status and age dynamics.

Fourth, while considering health-related vulnerability, women are more vulnerable than men due to widowhood. The data reflects that physical and perceived health can be more significantly affected due to widowhood for women than men. Also, considering survival dissimilarity between married and widowed men and women, the results suggest that women may have greater survival disadvantages due to widowhood than men.

Concluding remarks

This research has attempted to draw attention to widowhood and related vulnerabilities that the Indian population faces, as well as how gender influences these vulnerabilities. Although women are significantly vulnerable to the challenges associated with widowhood, men are not always immune to the repercussions of losing a spouse. Widowed men are also impacted by the death of their spouses, resulting in food shortages and concerns about abuse amongst widowed men in India.

Despite widowed women continuing to face significant financial obstacles, there are other areas of vulnerability, such as abuse or health-related issues, which require further attention from policymakers. However, the provision of financial assistance, such as widow pensions, is frequently emphasised in policies and programmes to address the obstacles that women encounter when their spouses die.

However, the Protection of Rights of Widows and Single Women and Abolition of Widowhood Practices Bill introduced in the Lok Sabha in 2022 is a commendable initiative that addresses a variety of issues, including preventing the abandonment of widows by in-laws, advocating for the rights of widows and their dependent children, providing free medical care, education, and legal aid to widows, and abolishing the cultural norms and practices associated with widowhood. It is time to ensure that no widows are left unprotected by the policy intervention aimed at providing them with the support and resources they need.

Babul Hossain is a post-doctoral researcher at the Luxembourg Institute for Health.