Murder holds a grim fascination for us. It is the irresistible hook at the heart of nearly every detective story. In South Asia, on a comparative basis, Indian rates of homicide are relatively modest (2.8 per 100,000 people), slightly higher than in Nepal (2.1) and Bangladesh (2.3), but lower than in Sri Lanka (3.4), and much lower than in Pakistan (4.3). All of these are far lower than in some nations where murder rates are very high—Jamaica (49.3 per 100,000 people), South Africa (45.5), and Mexico (24.9).

Around the world, most murderers are men and most victims are also men. In South Africa, for example, there were more than 27,000 murders in 2023, and 81.5% of the victims were men (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2023). There were roughly the same number of homicides in very much more populous India in 2022 (29,347), and 72.2% of the dead were men.

But these official homicide figures for India seriously understate the true number of women who are murdered each year. For what are no doubt historical and bureaucratic reasons, intentional deaths, including dowry killings (a distinctively Indian crime) and deaths from gang rapes, are recorded separately, obscuring the true extent of violence against women.

Murder for dowry (“dowry death” in police parlance) is essentially murder for gain. As Mohd. Umar puts it, “The harassment and violence against the bride revolves around the demand for more and more dowry which often culminates in the death of the bride … They are murdered for not bringing adequate dowry” (1998: 1).

It is not widely appreciated how significant dowry murder is in homicides in India—it is a major cause of homicide in some states.

As an identifiable sub-category of pre-meditated homicide, dowry murder has been the subject of successive bodies of legislation aimed at its suppression. In 1983, the Indian Penal Code (IPC) was amended to make the death of any woman in the first seven years of marriage subject to report, with the onus of proof being placed on her husband’s family to show that they were not responsible for it, either directly or by abetting suicide. In official statistics, which form the basis of this article, “homicide for dowry, dowry deaths or their attempts” fall under sections 302/304-B of the IPC. 1The data recorded by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) do not yet record data under the new headings established by the Bharatiya Nyay Sanhita in 2023. We lack independent assessment of the accuracy of NCRB data on dowry murder.

Section 304B states specifically, “Where the death of a woman is caused by any burns or bodily injury or occurs otherwise than under normal circumstances within seven years of her marriage and it is shown that soon before her death she was subjected to cruelty or harassment by her husband or any relative of her husband for, or in connection with, any demand for dowry, such death shall be called ‘dowry death’, and such husband or relative shall be deemed to have caused her death.”

As the statute indicates, immolation in the guise of a kitchen accident is the most common form of dowry murder. Belur and colleagues (2014) offer a discussion of the literature as well as a study of burns victims admitted to hospitals in New Delhi and Mumbai in 2014. What is surprising is that these dowry deaths are not included in those recorded under Section 302, which deals with “ordinary” homicide.

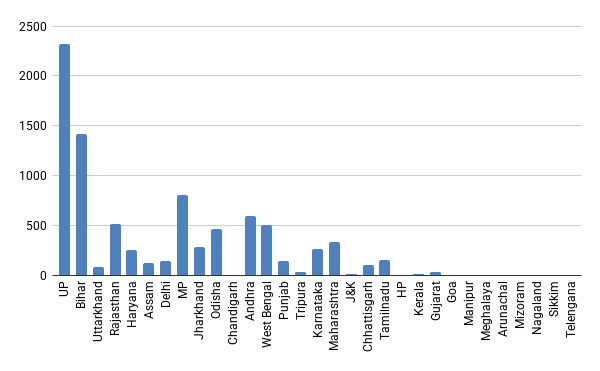

It is not widely appreciated how significant dowry murder is in homicides in India—it is a major cause of homicide in some states. In 2011, the last year for which we have Census data, there were 8,473 reported cases of dowry murder. This number constituted nearly 25% of all recorded murders in that year. Dowry murder was concentrated in the north Indian Hindi-speaking states of Haryana, New Delhi, Uttar Pradesh (UP), Madhya Pradesh (MP), Bihar, and Jharkhand, and the eastern state of Odisha. Almost 70% of the dowry murders in 2011 occurred in these states (Figure 1).

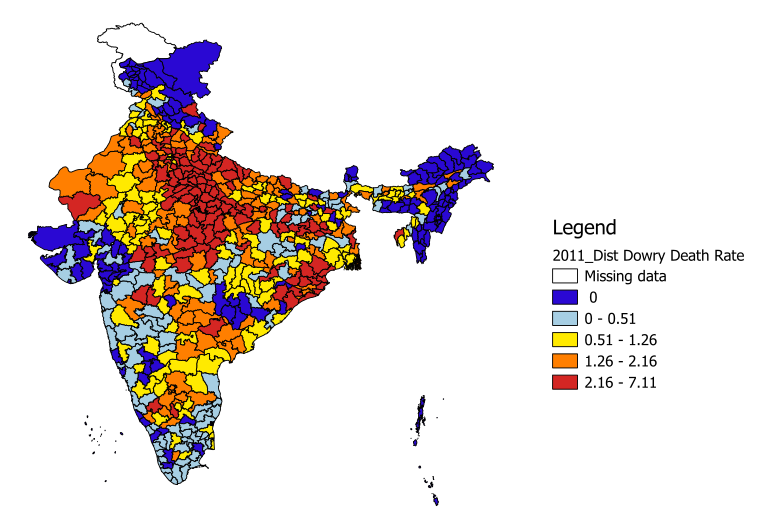

At the district level, we can see a zone of elevated dowry murder rates stretching south of Haryana, Delhi and western Uttar Pradesh through most of Madhya Pradesh, with concentric zones to the west and the northeast.

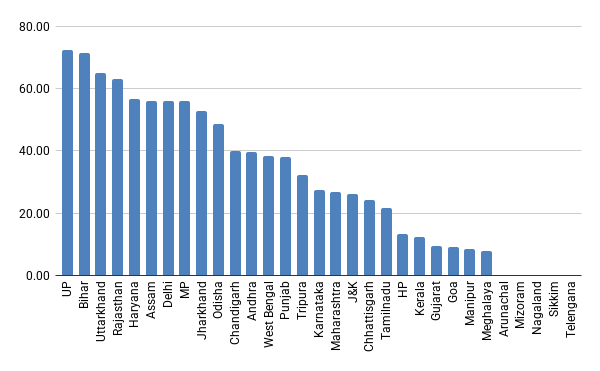

When we consider murders of adult women, the picture is even starker. In Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Haryana, Assam, Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Chandigarh, murders for dowry were responsible for 50% to more than 70% of all murders of adult women in 2011 (Figure 2). In Odisha, Chandigarh, Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, Punjab, and Tripura, dowry murders were between 30% and 40% of all murders of adult women. More than 20% of all murders in Karnataka, Maharashtra, Jammu and Kashmir, Chhattisgarh, and Tamil Nadu were for dowry.

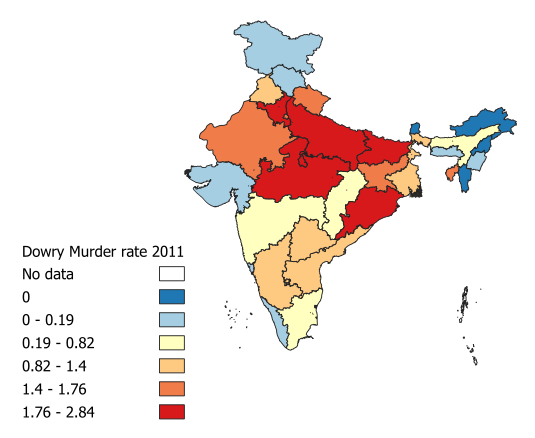

The rates of dowry murder were also the highest in these states (Figure 3). At the district level (Figure 4), we can see a zone of elevated dowry murder rates stretching south of Haryana, Delhi and western Uttar Pradesh through most of Madhya Pradesh, with concentric zones to the west and the northeast.

Figure 1: Dowry Murders, 2011

Figure 2: Dowry Murders as a Percentage of All Adult Female Murders, 2011

Figure 3: Rates of Dowry Murder in India’s States, 2011

Figure 4: Rates of Dowry Murder in India’s Districts, 2011

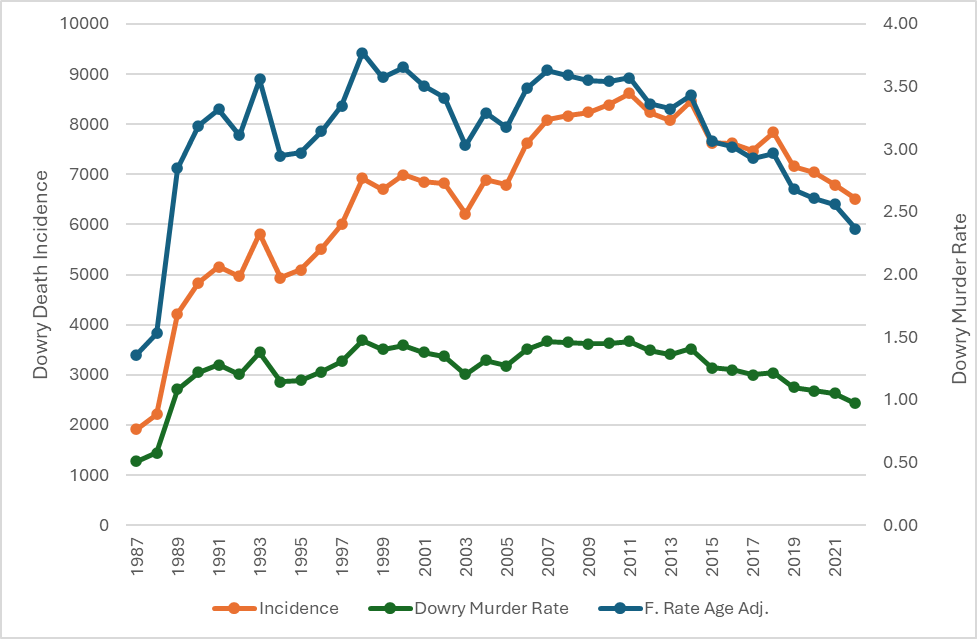

Figure 5: Incidence, Rate and Age-adjusted Rate of Dowry Murders, 1987 to 2022 (Per 100,000 population)

Across the nation, the number of murders for dowry appears to have risen quite sharply in the decade following the late 1980s (Figure 5). From just over 1,900 murders in 1987, the total rose to 6,000 by 1997. After an eight-year plateau in the mid-6,000s, numbers rose again after 2005 to a peak of 8,600 in 2011. Since 2011, numbers and rates have fallen steadily, totalling 6,516 in 2022.

A comparison between states over nearly two decades reflects the same trends. As we saw with the mapping, the states with the highest rates of dowry murders in the most years were Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, and Madhya Pradesh. There is some year-to-year fluctuation in rates—especially in smaller states such as Mizoram and union territories such as Chandigarh. What is also noticeable is a general downward trend in many states, which appears to have begun around 2011. In 2022, more than 50% of women murdered in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi were killed in connection with dowry. Assam is a significant exception to the trend—rates there rose to a peak in 2015 but have declined, and only a little over 40% of women were murdered over dowry.

The heavy concentration of dowry murders in North India—above all, in the Hindi-speaking states—prompt us to seek explanations for this regional difference. In her classic study of India’s kinship systems, Iravati Karve identified family organisation as one of the things “absolutely necessary for the understanding of any cultural phenomenon in India” (1965: 1). The family itself has two components, the structure of kinship and the joint family (Karve 1965: 8-9).

Karve distinguishes the kinship organisation of north India (Punjab, Kashmir, Uttar Pradesh, and parts of Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Bengal, and Assam), and the Adivasi-dominated districts of central India (in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha, to which we must add Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand) with that of the southern zone (Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu) (1965). What is relevant to our consideration of dowry murder is that in the northern kinship system, brides are sought from families with which there has been no intermarriage in (commonly) seven generations (Karve 1965: 117). Thus, a bride is married into a family of strangers and will but rarely return to her paternal home (Karve 1965: 127ff.). In the southern kinship systems, by contrast, the primary focus is on reinforcing existing kinship ties through mechanisms such as cross-cousin marriage.

At first glance, it appears more likely that brides in North India are seen as instruments of value, making the idea of their murder more conceivable than in the South.

In the south, “one’s own extended family is also one’s family by marriage, and so the complete separation between one’s family of birth and family by marriage, which is evident in the northern terminology, is absent in the Dravidian kinship terms … A girl does not enter the house of strangers on marriage as in the north, her husband is not the perfect stranger to her as he is to her northern sister … Nor does marriage symbolise separation from the father’s house for a girl. A woman in the south lives and moves freely in her father-in-law’s house” (Karve 1965: 241-42).

At first glance, it appears more likely that brides in North India are seen as instruments of value, making the idea of their murder more conceivable than in the South.

When we explore the statistical implications of Karve’s factors, the results are striking. The strongest correlations are with two things—the percentage of women who have migrated from their birth district, which partly reflects differences between northern and southern marriage practices, and the average household size, which indicates the prevalence of joint families.

Female mobility is highly correlated with the rate of dowry deaths (r = .73, sig. @ .001), implying that slightly more than half of the difference in dowry rates between states is explained by the difference in kinship systems alone. Average family size is also strongly correlated with dowry death rates (r = .71, sig. @ .003), reflecting the fact that many dowry murders take place in undivided joint families. However, because female mobility and family size are themselves very highly correlated, family size adds little additional explanatory power when the two are considered together.

The strong association between rates of dowry murder and fundamental aspects of Indian society must make us pessimistic about the possibility of policy interventions preventing such intentional murders. However, dowry murder rates have fallen substantially since 2011, which suggests that change is not only possible but also happening.

One possible explanation for the declining rate of dowry murders emerges from those same fundamental social factors. The states where dowry murders are the highest are also those where sex ratios are the most masculine. Evidence suggests that there is a distinct north Indian “bride shortage”, especially in states like Haryana. Not only are men in Haryana seeking brides from states as far afield as Kerala, but they are also paying a “bride price” to secure wives. One partial test of this hypothesis is to compare the rate at which dowry murders declined in the Hindi belt between 2011 and 2022 with the degree of masculinisation of sex ratios. The association between the two is strong, suggesting that where the bride shortage is most acute, the rates of murder for dowry have fallen fastest.

As my late friend economist Dharma Kumar once remarked when we were discussing the implications of the growing masculinsation of sex ratios, eventually the law of supply and demand must assert itself. Is it possible, perhaps, that we are seeing the first signs of a transition from dowry to bride price, and with it a revolutionary change in social attitudes to girls and women?

This article has been adapted from “‘They Did Not Have to Burn My Sister Alive’: Causes and Distribution by State of Dowry Murders in India.”, published in 2022.