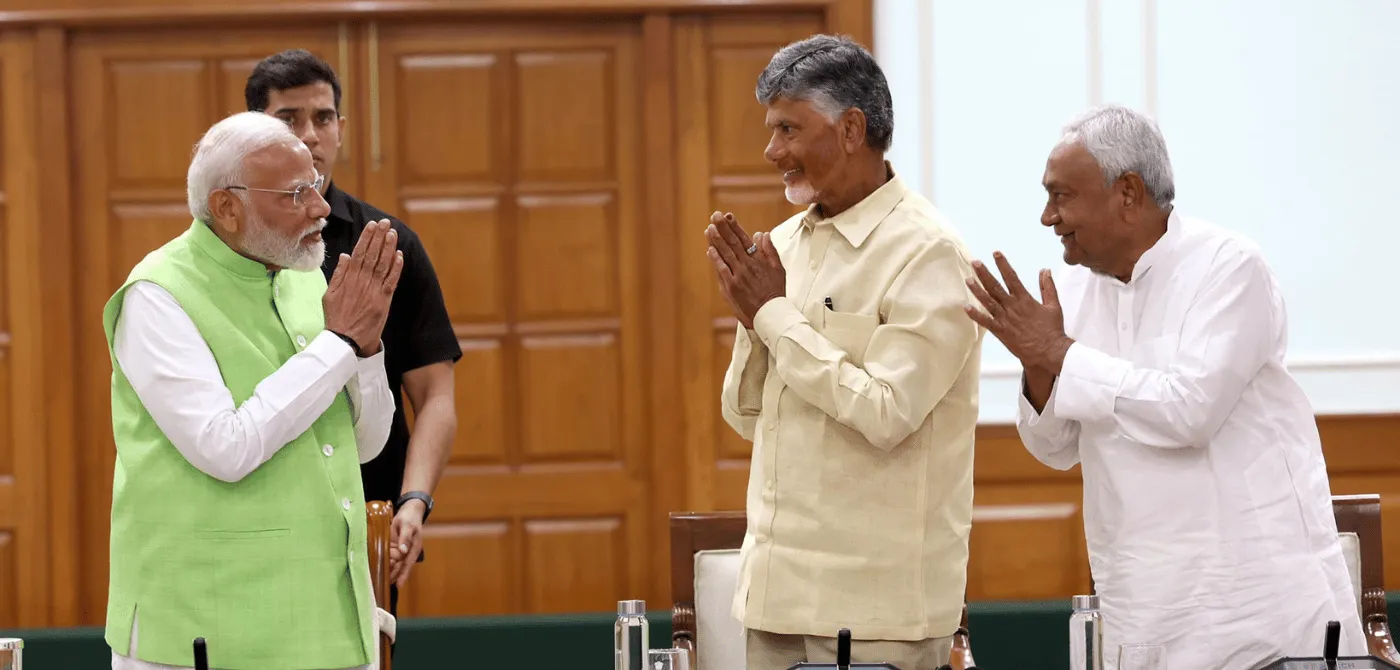

Narendra Modi may have returned as prime minister for the third time, but the electorate has punctured the aura around him and the halo of invincibility around the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Along with a resounding opposition in Parliament for the first time in over a decade, this moment signals the triumphant return of coalition politics.

The BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) is crucially dependent on the support of two powerful regional parties: Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal-United (JDU) and N Chandrababu Naidu’s Telugu Desam Party (TDP). The good showing by the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), came through a range of regional parties coalescing with the Indian National Congress (INC) into a cohesive front.

The return to prominence of the regional parties at the centre notwithstanding, one might ask: why are there only two parties that can lay serious claim to national status? As per the Election Commission of India (ECI) records on March 2024, there are 6 national parties, 57 regional parties, and 2764 unrecognised parties. Over 70 years since the first election, why hasn’t a third single party alternative arisen?

Why have the regional parties with so many decades in the field failed to transform into national players?

Regional parties vs Hindi unity

Nationwide parties generally had some mass movement and invoked it regularly in their outreach to all corners. It was the freedom movement for the Congress, the Ram Janmabhoomi for the BJP, and the worldwide working-class struggles and revolutions for the Left.

There is that north-south divide which unites them. There also is a south-south divide, an east-east divide, a west-west divide, and a north-east-north-east divide in India.

Big non-north-Indian states like Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, or Andhra Pradesh base their politics on their linguistic or regional distinctions. Parties there face internal competition at home: two or more major native parties vying for state power, which includes the state cadre of national parties like the BJP or the Congress. Many of these parties are dynastic, creating self-harming internal factions that we have seen with the Shiv Sena and the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) in Maharashtra. Many others are, in reality, sub-regional satraps operating in just one sphere of the state. The Janata Dal-(Secular) in Karnataka is influential only in the Cauvery river belt of Karnataka; or the undivided Shiv Sena’s reach rarely extended beyond the Mumbai and Konkan regions of western Maharashtra. In the North East, states are internally riven along ethnic lines: two or more parties face off against each other, along with the local BJP or Congress units.

These factors leave the non-northern regional parties little time, space, resources or intent, to go out of their home turf, to take on the BJP (or the once strong Congress) machinery across the Hindi heartland.

Multiple divides

The current moment of an opposition resurgence is an all-too-rare kind of regional party bonhomie. We see exceptional southern unity in that none of the states has a BJP government in their respective Assemblies. Nearly all of them are railed against the centre over public finances owed to them under federal law that they accuse the centre of not parting with.

There is that north-south divide which unites them. There also is a south-south divide, an east-east divide, a west-west divide, and a north-east-north-east divide in India.

Nearly all these states in the south, west, east or north-east, do not necessarily share warm relations with one another over many common concerns. Karnataka and Tamil Nadu have tussled over the waters of the Cauvery since before Independence. Maharashtra and Karnataka clash over ownership of villages and towns at their borders. West Bengal shares relations that are not always friendly with some of its neighbours Bihar, Odisha, Sikkim, and Jharkhand.

The north Indian states fare poorer than the south, this level of acknowledging local aspiration has made the north appear more united than the rest of India.

Few north Indian states suffer such interstate disadvantages. Barring Punjab and Haryana, borders that Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttarakhand collectively share with one another seldom prompt conflicts that we notice in the south, east, west, or northeast of India. In the past, sub-regional aspirations in the Hindi-speaking or Hindi-knowing states led to the carving out of Uttarakhand from UP, Jharkhand from Bihar, and Chhattisgarh from Madhya Pradesh. Although on most social indices, the north Indian states fare poorer than the south, this level of acknowledging local aspiration has made the north appear more united than the rest of India.

Caste, class, dialect, sect, subsect, religion, community may differ in north India. Yet it still speaks, and can converge on the notion of standard Hindi. It can literally and figuratively speak as one to a great degree. (To be sure, the history of Hindi’s domination in north India is not natural and was almost an imperial project.) The states of the rest of India lack that taken-for-granted advantage. They have rocky relations with one another and literally and figuratively speak in different tongues. And excepting gross maltreatment, the south (or the ‘Rest’) appears tentative to band together on many issues, while the north can close ranks when required.

All these considerations make it well-nigh impossible for these parties to dare the BJP or the Congress in faraway north India.

Northern attempts

Some of these parties, mainly north Indian, did on occasion labour far from home. These were largely last-minute efforts, and rarely arising out of long-term planning. Uttar Pradesh’s Samajwadi Party with their then alliance partner the Bahujan Samaj Party contested elections in Maharashtra in the 2019 Lok Sabha poll. The JDU- once won a parliamentary seat from Lakshadweep, in 2004. In 2023, the BSP ran and lost for assembly seats in Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Telangana, and won two seats in Rajasthan.

The Aam Aadmi Party’s rising graph has been knocked down by the 2024 Lok Sabha election, but it remains a rare instance of successfully taking the fight to the national parties. Like the national parties, the AAP has built on its founding moment in the pan-national India Against Corruption movement. It twice defeated entrenched players like the BJP and the Congress in the Delhi state elections, and both of them and local heavyweights like the Akali Dal and the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) in the last Punjab state polls. It may have drawn a blank in the Karnataka elections in 2023 and in the Goa polls, but the show of intent was unmistakeable.

Imagine a Periyarite imprint on a city like Varanasi.

The AAP’s successes contrast with the left’s storied and wrought pasts and uncertain future. The left parties once had currency outside their one-time strongholds of West Bengal and Tripura, (it still retains Kerala, but in this election the BJP made inroads by winning the Thrissur parliamentary seat courtesy Malayalam actor-turned-politician Suresh Gopi). They attracted working-class people in industrial towns and the rural countryside. Yet the left could not grow across India. Even with a leftist beehive as Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, it struggled to create a buzz in the capital’s assembly or national elections. A poor understanding of the primacy of caste in India, a rigid adherence to their ideology and a stodgy approach to mass contact non-left audiences quickened its disappearance from the fringes of mainland India. In Mumbai, it met a bloody termination at the hands of the Maratha nativist leader Bal Thackeray and his Shiv Sena in the 1970s and 1980s, which too was clueless about going all-India.

***

It should be so dismaying to Maharashtrians that Maharashtra has yet to produce a party that could be the queen and not queenmaker of Indian politics. Even with its hoary history of social reform, saint poets, sizzling freedom fighters, anti-caste icons – many of who are household names and lore in India – Maharashtra-based parties failed to transcend their state.

The undivided Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) has occasionally won Lok Sabha and assembly seats in states as disparate and distant from its home as Lakshadweep, Meghalaya, Manipur, Kerala, Jharkhand and Bihar. Yet regardless of its name, it’s hardly a ‘national’ phenomenon. The undivided Shiv Sena’s crowning moment on an away pitch was in early 1999, when its Delhi unit dug up the then Feroz Shah Kotla Stadium pitch to stall an imminent Indo-Pak cricket Test match. (This sole instance when the Shiv Sena had any bearing outside western Maharashtra might have made for an apt Bal Thackeray sketch.)

As in Maharashtra, one expected the Tamil parties to have challenged the BJP or Congress in north India. Like Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu too has a set of relatable sociopolitical iconographies searching for wider dissemination and acceptance. Anti-caste Dravidian ideology could have found a home through the caste-wracked Gangetic plains of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The state and its parties conflating its identity with the Tamil language has swelled local pride, but alienated them nationally.

The DMK and the AIADMK confined themselves to home territory and perpetually having to negotiate with the nationwide parties (both parties have been junior alliance partners to either or both the Congress and BJP). In December 2023, the prime minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the Kashi Tamil Sangamam in Varanasi. It was a way of commemorating and arrogating to himself and the BJP a slice of Tamil civilisation. A more proactive Tamil party may have made such overtures to the north long ago and subsequently built a grassroots squad there. Imagine a Periyarite imprint on a city like Varanasi.

Regardless of what has transpired in the 2024 Lok Sabha poll, the AAP, and to an extremely minor extent the AIMIM, appear to have the mentality to take on the BJP and Congress in disparate parts of India.

In many ways, similar concerns beleaguer redoubtable regional paragons in east India like the All-India Trinamool Congress in West Bengal or the now fully defeated Biju Janata Dal (BJD) in Odisha – which remained in power for 24 consecutive years in the state and was a loyal supporter of the BJP-led NDA. With so many Bengalis and Odias living across Indian cities, towns and villages over generations, did they not deserve a political party from their state aspiring to be the nation’s lodestar? Why haven’t the Trinamool (which contested a few Lok Sabha seats in Assam and Meghalaya in 2024 and lost) or BJD attempted to more seriously politick away from home yet? Utterly similar questions come to mind when we observe the potential of the native parties of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. The Telugu-speaking regions have a long history and affinity with Hindi and Urdu. The Deccan plateau and the Hyderabad vicinity presents such a confluence of the many threads that form the tapestry of India. Why haven’t they thought of themselves as national players and not only movers and shakers in AP or Telangana?

The Telangana-headquartered All India Majlis-e-Ittahadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) translates to the All-India Council for the Unity of Muslims, which would imply travelling across the country. The AIMIM has fought elections in Maharashtra, Bihar, West Bengal, Karnataka, with some promising results. But it is a long-term player, aiming to be a sole voice for Indian Muslims, who too are separated by region, language, caste.

Both AIMIM (like the later AAP), sets store on ground-up politicking and eschewing parachuting candidates to fight elections in constituencies away from home. Both AIMIM (and the later AAP) underscore the significance of civic elections. AIMIM won in the city of Nanded in Maharashtra in 2012 and in Bidar and Basavakalyan in northern Karnataka in 2013. Given the situation of Muslims in India today, for the AIMIM to spread India-wide is top take on the Congress and other parties. That is nothing short of remarkable for a party that knows a majority of India that is Hindu might not vote for it and still soldiers on.

Regardless of what has transpired in the 2024 Lok Sabha poll, the AAP, and to an extremely minor extent the AIMIM, appear to have the mentality to take on the BJP and Congress in disparate parts of India. That it is only those two – at varying ends of the political spectrum – willing to fight the big fight, speaks volumes on how the well-established regional parties have disappointed their voters and ceded national ground to the sometimes less deserving BJP or Congress on a platter.

Rahul Jayaram is a teacher, writer and poet living in Bangalore.