Verdict Karnataka 2023 has an unmistakable class character to it. The fury of the poor, who had been reeling under inflation and unemployment, put an end to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP’s) dreams. The party’s defeat would have been even more humiliating but for the support it received from better-off voters in the more urbanised regions of the state.

Even a cursory glance at the results shows that the economic situation influenced the people’s choice. In the economically advanced districts of Dakshina Kannada and Udupi on the west coast, where the service sector dominates, the BJP swept all but two of the 13 seats. But in the economically backward Yadgir district in the north, where agriculture is the main occupation, the BJP drew a blank. Except for the two relatively better-off districts of Chickmagaluru and Kodagu in the south, the BJP’s performance suffered in regions where very little development had occurred in the last four years.

BJP Hubris

During its tenure, the BJP government was keen on high-profile infrastructure projects such as the Bangalore-Mysore Expressway and a string of new airports. It had several welfare programmes but none of them stood out. In a pre-poll survey conducted by Kannada web portal eedina.com, none of the 40,000-odd respondents could name a single welfare programme of the state government.

BJP leaders routinely made fun of the pro-poor programmes introduced by the earlier Siddaramaiah government (2013-18) and even stopped some of them. The free rice for below the poverty line families was slashed and the Indira Canteens, which supplied breakfast and meals in urban areas at a highly subsidised rate, were discontinued. This, along with a steady rise in the price of cooking gas, added to the burden of the poor.

The BJP’s election strategy was insensitive to the poverty and inequality one sees in most of the state beyond the glitter of its urban centres. The party tried to take credit for schemes such as the direct transfer of cash to farmers under the PM Kisan Scheme. However, that did not create a constituency of beneficiaries large enough to beat the effects of anti-incumbency. For a people struggling with rising prices, the government’s welfare programmes made little sense.

The BJP’s election strategy was insensitive to the poverty and inequality one sees in most of the state beyond the glitter of its urban centres. … For a people struggling with rising prices, the government’s welfare programmes made little sense.

A farmer in a village in the southern district of Hassan said a few days before the election, “I got Rs. 6,000 last year in three instalments (under PM Kisan) but during the same period, the government took more than three times that from my pocket by increasing the prices for seeds, fertilisers, and cooking gas.” In many places, people wondered why the government had reduced the quota of free rice from 10 kg to 4 kg while women wanted to know if the government wanted them to return to burning firewood by increasing the price of cooking gas supplied under the centre’s much-publicised Ujjwala Yojana.

Voter Preference Historically

The poll results underline the importance of political parties aligning their strategies with historical realities. The poor rejected the BJP all over the state. A caste-based analysis of the results shows that constituencies dominated by the Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes (SC/STs), the two groups with the highest concentration of the poor, were won by the Congress. It was a reversal of the trend in the recent past. Women, who are relatively less well off than men across all social classes, also favoured the Congress.

Across caste lines, those in the lower income brackets deserted the BJP this time. The Congress strategy took into account the economic tensions in the state. It began with the pandemic when the Congress tried to reach out to the people by making its members of the legislative assembly (MLAs) contribute a month’s salary for Covid-19 relief activities. Since then, the party had been speaking of social welfare and poverty alleviation.

The guarantee schemes (free rice, free power up to 200 units, Rs. 2,000 in cash to female heads of households, unemployment allowance, and free bus travel for women) announced before the elections resonated with the poor. In the end, they gave the Congress an impressive tally of 135 seats. The state’s electoral history shows that governments that failed to strike a chord with the poor have suffered while those that had a re-distributional agenda have been rewarded.

In the first decade of this century, the Congress regime led by S.M. Krishna during 1999-2004 earned a reputation for promoting a development model that focused on the information technology-led industries in Bangalore and other urban areas. A perception soon gained ground that the government was elitist, anti-poor, and anti-farmer. Totally oblivious to this undercurrent of discontent, it held the 2004 election five months before it was due and was defeated.

The state’s electoral history shows that governments that failed to strike a chord with the poor have suffered while those that had a re-distributional agenda have been rewarded.

In the 1970s, Devaraj Urs became the longest serving chief minister of the state on a pro-poor agenda of land reforms, job reservations for the poorer Other Backward Classes (OBCs), and a slew of welfare measures, including a rural employment guarantee programme and a free housing scheme. Urs won a second term in 1978 despite an anti-Congress wave sweeping the country after the emergency primarily because of his pro-poor image.

An exception to this trend was the Congress government led by Siddaramaiah between 2013 and 2018, which lost the election despite having had a pro-poor agenda. Analysts point out that Siddaramaiah lost mainly because he rubbed the two dominant castes, the Lingayats and Vokkaligas, the wrong way. The Congress vote share in that election went up to 38% from 36% in 2013.

In any case, the image of being a pro-poor leader stayed with Siddaramaiah and he apparently became more popular after losing the election. It was this, and state Congress President D.K. Shivakumar’s organisational ability, that helped the Congress win this time. After Urs, Siddaramaiah is the only leader in Karnataka who has become the chief minister again after completing a full term in office. What they both have in common is a reputation for being champions of the poor.

Urban Exception

In terms of per capita income, Karnataka is one of India’s richer states in India. But this growth in per capita income has been primarily because of the huge contribution of just one district to the state’s gross domestic product (SGDP). Bangalore Urban district, which includes Bangalore city, accounts for 36% of the SGDP with just 16% of the population, according to the Karnataka Economic Survey 2020-21. The remaining 29 districts with 84% of the population contribute 64% of the SGDP, or an average of just 3% to 4% each. The elections have always been fought and lost in the rural hinterlands of the state. Any election strategy that ignores the gross inequalities in the state does not work.

The BJP’s strategy worked only in urban areas. In Bangalore, for example, of the 28 seats, the BJP won 15. This could be seen as an approval for the BJP’s development strategies, which were rejected in rural Karnataka. In the 2004 election, Chief Minister Krishna’s urban-centric development model was approved by Bangalore, but it did not find favour in the rural parts of the state. That Karnataka’s politics is sensitive to the economic situation has been known for long.

State vs Centre Preference

The BJP’s election strategy was also not aligned with another long-term trend in Karnataka politics. Historically, the state has not preferred the party in power at the centre to rule it, but the BJP was pushing the idea of “a double engine government” (the same party ruling at the centre and the state) as the best way of achieving faster development.

Since 1983, when the first non-Congress government came to power in Karnataka, the state’s voters have elected a party in the opposition at the centre to rule them. In 1983, Karnataka elected the Janata Party when the Congress was in power at the centre. In 1985, Karnataka re-elected the Janata Party while a Congress government led by Rajiv Gandhi was at the centre.

Historically, the state has not preferred the party in power at the centre to rule it, but the BJP was pushing the idea of ‘a double engine government’ as the best way of achieving faster development.

In 1989, the Janata Dal held power at the centre but Karnataka voted overwhelmingly for the Congress. In 1994, the Congress under Prime Minister Narasimha Rao was in power at the centre, but Karnataka voted for the Janata Dal. In 1999, when the BJP came to power at the centre, Karnataka chose the Congress.

In 2004, the roles were reversed. The Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) assumed power at the centre but Karnataka rejected it, which eventually led to two coalition governments. In 2008, the UPA was still in power at the centre but the state elected its first BJP government.

In 2013, when the Congress came to power in Karnataka, it was in power at the centre too. This was an exception. Within a year, the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) replaced the UPA government at the centre.

In 2018, as the BJP continued to hold power at the centre, a Congress-Janata Dal (Secular) [JD(S)] coalition assumed power in the state. It was only because of the BJP’s Operation Kamala that Karnataka had the same party in power as at the centre between 2019 and 2023. This “double engine” government was not the choice of the people—it was imposed on them by the BJP through horse-trading.

It seemed as if the BJP, especially its national leaders, were pushing Karnataka towards a political culture that was very different from what it has been known for. It was hardly surprising this did not work.

Karnataka does not have a regional party but its version of regional politics has been to avoid being ruled by the party in power at the centre. Prime Minister Narendra Modi intervening in the state’s politics and advocating a “double engine” government was certainly not what the people wanted. It seemed as if the BJP, especially its national leaders, were pushing Karnataka towards a political culture that was very different from what it has been known for. It was hardly surprising this did not work.

Communalism Undefeated

What do the Karnataka election results tell us about communalism, which was also a crucial part of the BJP’s electoral strategy? Unlike what many analysts have observed, the result does not show that the electorate has decisively rejected communal politics. In pre-poll surveys conducted by eedina.com and the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), Delhi, voters did not assign any significance to communal politics during the BJP’s four-year rule as a determinant of their electoral choice.

In other words, people who did not vote for the BJP did not do so because they thought it was communal or its politics were opposed to the constitutional ideals of secularism and fraternity. If livelihood issues such as inflation and unemployment had not been so pressing, they might have voted for the BJP despite its communal politics.

More importantly, in the economically better off parts of the state, such as coastal Karnataka, where communalism has taken deep roots, the BJP managed to do well despite the anti-incumbency factor. The region has been considered the BJP’s laboratory of Hindutva politics and it has witnessed numerous communal incidents, such as moral policing, the economic boycott of Muslims, and a string of communal murders.

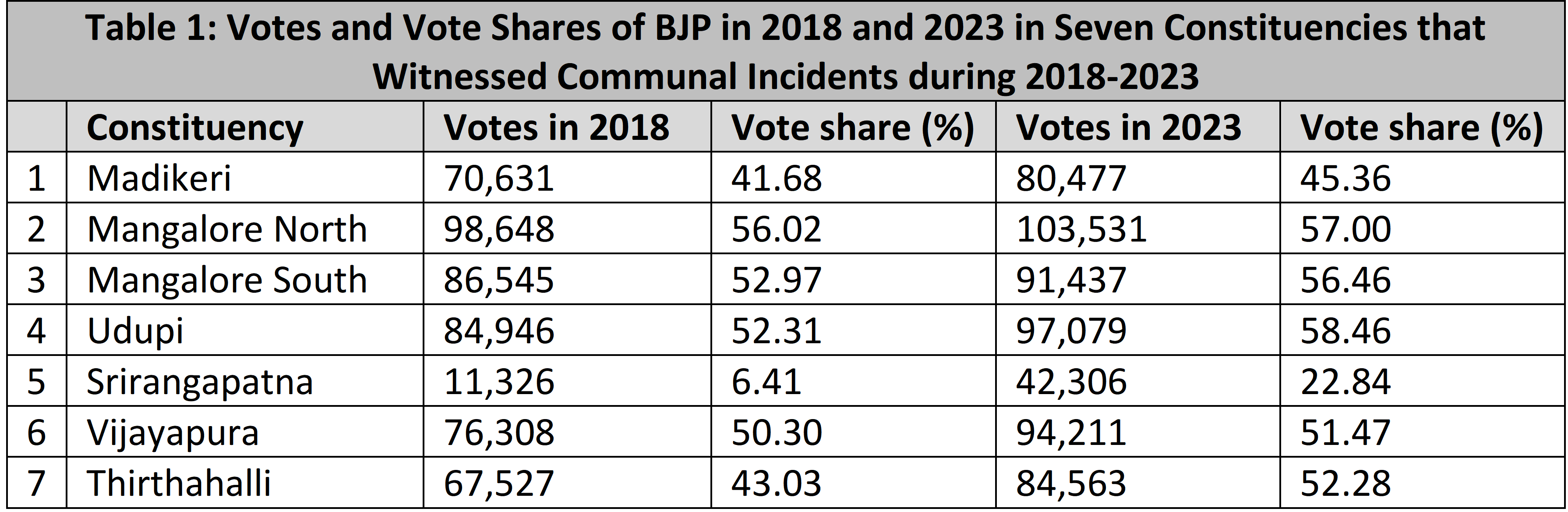

Across the state, the constituencies that had communal flare-ups in the last few years showed an increase in the vote share of the BJP.

The example of the coastal region suggests that with a well-entrenched communal divide, the BJP can hope to win an election in Karnataka without having to worry much about the quality of its governance. The state’s two coastal districts have been economically and educationally advanced for several years now, and the support that the BJP’s communal politics has received there suggests that the growth of the economy and communalism have gone hand in hand.

In southern Karnataka, where the BJP hardly had any votes till 2018, its candidates improved their vote share this time though they were not able to win. This partly explains why the BJP has retained the 36% share of votes that it secured in 2018. The BJP lost the election, but its vote share, which began rising in 1991, remained constant this time.

Across the state, the constituencies that had communal flare-ups in the last few years showed an increase in the vote share of the BJP (Table 1). In Udupi, which was at the epicentre of the hijab controversy, the BJP’s winning margin in 2018 was 12,000 votes. This time, it was more than 32,000 votes.

In Srirangapatna, where the Sangh parivar has been trying to create an Ayodhya-like controversy by claiming that a masjid was a Hindu temple, the BJP’s vote share increased from a mere 6% in 2018 to 23%. The BJP bettered its vote share in Mangalore North (from 56% to 57%) and Mangalore South (from 52% to 56%), both constituencies that had seen a spate of communal incidents, including two murders.

In Madikeri, the headquarters of Kodagu district, where at least 10 communal incidents were reported between 2019 and 2022, the BJP’s vote share improved from 41% to 45%. In Thirthahalli in Shimoga district, another BJP bastion, the party’s vote share increased almost by 10 percentage points, from 43% to 52.28%. In Vijayapura constituency in north Karnataka, represented by firebrand Hindutva leader Basavanagouda Patil Yatnal, the BJP’s vote share increased from 50% in 2018 to 51% in 2023.

All of this goes to show that while the BJP lost the election, its core political agenda, which it had been trying to establish for decades, has not been defeated.

Return to Two-Party Politics

Verdict 2023 points to the imminent return of Karnataka to two-party politics after two decades. The JD(S), which has been a prominent third player, won just 19 seats this time (37 in 2018) and its vote share dropped from 18.6% in 2018 to 13%. The future for the party does not look promising with age catching up with former Prime Minister H.D. Deve Gowda. Although his son H.D. Kumaraswamy had brief stints as chief minister in 2007 and 2018, he has been presiding over a steady decline in the party’s fortunes.

After the dominance of the Congress ended in 1983, there was a competition between the Congress and the Janata Party (later Janata Dal) in Karnataka for more than a decade. This changed after 1994 when the BJP emerged as a serious contender for power. In 1999, it edged out the JD(S), which was a splinter group of the erstwhile Janata Dal, to occupy the second slot. Since then, the BJP has been the main opponent of the Congress while the JD(S) has been confined to some parts of the old Mysore region.

With the loss suffered by the JD(S) this time, Karnataka seems to be slipping back to the days of a two-party contest. This would be to the advantage of the BJP because the state’s electorate has been alternately giving power to one of two parties since 1985. The BJP can hope to eventually bounce back, maybe even with a majority—something that has eluded it so far.

A. Narayana teaches public policy and governance at Azim Premji University, Bangalore.