Indians are entitled to take pride in their ancient democratic states and institutions. But what is the place of India in the history of democracy worldwide, and in relation to claims for ancient Greece? A rising tide of autocracy at this moment in world history makes the history of democracy more urgent than it has been since the struggle for freedom from British rule.

Sumit Guha’s excellent article Was India the Mother of Democracy? suggests that the new book by the Indian Council of Historical Research, India: The Mother of Democracy (Tanwar and Kadam 2022) rests on a doubtful project of finding a unique parent of democracy, a single centre from which all democratic institutions have spread. It is more satisfactory to say that democratic tendencies have sprung up in many places and “the Indian subcontinent has been one of the sites where the idea of limited government and countervailing institutions has existed through time.” This is entirely convincing.

The same criticism applies to another, rival, claim: that Athens is the mother of democracy. It is worth our while to examine it because it remains a potent theme. For a very long time, the history of democracy, especially in the West, was a special province of the study of Greek and Latin, and Athens was its obligatory starting point. It is only now that this is beginning to change, long after India has won its independence and become a nation-state, inaugurating the era of massive decolonisation after World War II, winding up the European empires and turning ex-empires and their subject countries into democracies in the blinking of an eye.

It is more satisfactory to say that democratic tendencies have sprung up in many places and “the Indian subcontinent has been one of the sites".

Read the Wikipedia article on the history of democracy and you will see that Athens remains the point of departure. The perspective is mainly Greco-Roman, even while it makes gestures to early India and other ancient civilisations. Those gestures are as yet not robust enough to fundamentally change the overall shape of the narrative, one that makes Europe the single point of emergence, from which democracy spreads until it is universal.

The theory of British rule

In the 18th century, Britons frankly acknowledged that their rule of India was based upon self-interest and would be irksome to Indians. Here is what the governor-general, Warren Hastings, said in the preface to the first translation of the Bhagavad Gita into English, by Charles Wilkins (1785):

Every accumulation of knowledge, and especially such as is obtained by social communication with people over whom we exercise a dominion founded on the right of conquest, is useful to the state: it is the gain of humanity: in the specific instance which I have stated, it attracts and conciliates distant affections; it lessens the weight of the chain by which the natives are held in subjection; and it imprints on the hearts of our own countrymen the sense and obligation of benevolence.

This avowal of the mercenary character of empire, though elegantly stated, could not last. As the 19th century began, the script was changed. That foreign rule was despotic because it was not answerable to the will of the ruled was increasingly a problem for the new British theorists of popular sovereignty, but its irksomeness to the people of India was turned into its opposite, the theory of Oriental Despotism: that it was customary and what Indians wanted. The historian Vincent Smith (1924) argued that India being made of clashing social molecules (the castes), it was never so happy as when it was ruled by an imperial power, as under the Mauryans, the Moghuls, or the British. The rule of the British, however, was now to be a school for Indian self-rule, to be achieved at some distant time. Call this the theory of tutelage. In their own eyes, the foreign rulers of India became its benefactors.

The theory of tutelage assumed there had been no democracy in ancient India above the level of the village panchayat

The theory of Oriental Despotism was made from a remark by Aristotle about the difference of the Greeks and their government from that of the Persians. The French political theorist Montesquieu revived and expanded this idea in 18th century France. There was debate amongst the British over whether the idea applied also to ancient India. Sir William Jones (1782:513) said that the theory of Oriental Despotism was “big with ruin” for the British. Yet, over time, it became the settled view. The theory of tutelage assumed there had been no democracy in ancient India above the level of the village panchayat and was consistent in this way with the claim that Athens was the mother of democracy.

New scholarship on democracy in ancient India

A wave of new scholarship on democracy in ancient India commenced at the opening of the 20th century, with the book Buddhist India by T.W. Rhys Davids (1903), who had been in the imperial service in Ceylon, bringing to bear the valuable evidence of the Theravada canon of Buddhism and the monastic chronicles of the island to the history of north India in the age of the Buddha. Republics, called sangha, were important forms of aristocracy and democracy at the time, side by side with kingdoms. Both Buddha and Mahavira came from republics of this kind. It is not surprising, then, that the Buddhist order of monks, also called sangha, was modelled on the deliberative bodies of the republics.

An entire new generation of historians of ancient India that came of age during the freedom struggle took part the culture-war over the interpretation of India’s past.

Soon after, K.P. Jayaswal, an Oxford-educated barrister from Bihar, connected this evidence with that of the Mahabharata and the then-recently discovered Arthashastra of Kautilya. His highly influential book, Hindu Polity (1924) argued that kingship in ancient India was constitutionally limited by a parliament-like bicameral body representing the people.

Some believed that Jayaswal’s argument had gone beyond the evidence. But an entire new generation of historians of ancient India that came of age during the freedom struggle took part in the culture-war over the interpretation of India’s past being fought with the British at the same time.

Beginning in the 1920s, there was a burst of new research on political history. Its makers became the leading historians of their time: B.C. Law (1926) on the Pali literature of Ceylon, R.C. Majumdar (1922) on corporate life in ancient India, U.N. Ghoshal (1927) on political theories of ancient India, A.S. Altekar (1927) on village communities, and many more. Jagdish Sharma (1968) at the University of Hawaii in the United States extended the scholarship on republics to the Vedic period.

After Independence, political theory of ancient India was made a fixture of the history syllabus in university departments of history. R.S. Sharma (1959) and A.S. Altekar (1958) wrote leading works of synthesis.

Where things stand now

The rediscovery of the Arthashastra occurred at the start of the freedom struggle. The scholarly aspect of that struggle, over the history of the Indian state, asked whether it was at bottom despotic or answerable to the people. The Arthashastra (Book 11) is clear: ancient India knew kingdoms (rajya), but also republics (sangha). Some of them followed farming and other economic endeavours as well as the military arts, that is, true democracies of farmer-soldiers. Others called themselves rajas, presumably large landowners maintaining servants working the land – in other words, an aristocratic stratum of the wealthy who shared power amongst themselves and decided affairs of state in assembly.

Thus, the universe of political forms is of three main kinds, depending upon where sovereignty resided, much as in Greek political thought, corresponding approximately to what the Greeks called the rule of the one, the few, or the many.

There was a rough similarity in India to the threefold political categories of ancient Greece, together with a lively growth of cities in the period of the rise of Buddhism and Jainism.

A fourth political kind was constituted by the ‘forest people’, whose ruler was sometimes called a forest-king (atavika-raja), and, according to the Arthashastra, might take part in a disputed succession and was thinkable as a successor to kingship over an agrarian population (Trautmann 2023). Sumit Guha (2021) surveys the many forms of historical interactions between tribes and states in Asia, an essential dimension of the new history of democracy that is needed.

Thus, there was a rough similarity in India to the threefold political categories of ancient Greece, together with a lively growth of cities in the period of the rise of Buddhism and Jainism (6th and 5th centuries BCE). Into these conditions Alexander of Macedon brought his army against the Persian emperor, and into India for a period of three years of empire-making in the Indus Valley. After his departure, Megasthenes came on embassy from Seleucus to Chandragupta Maurya, leaving a memoir of India which survives, but only in fragments preserved by later writers (Stoneman 2022).

The testimony of Greek writers about Alexander’s military incursion into the Indus Valley, and about Megasthenes’ embassy to Chandragupta in the Valley of the Ganga, brief as it is, is valuable in giving points of connection with the political categories of the Greeks. India, in this testimony, had polities based upon kings (basileus), or self-governing “cities,” that is, states (poleis autonomoi), some of them governed by aristocrats, others democracies ruled by the free males. Diodorus of Sicily uses the very word democracy (democratia), saying that in the mythic past the kingship of the first ruling line of India was replaced by democracies.

The 18th century doctrine of Oriental Despotism goes against the ancient sources that survive on Alexander and Megasthenes in India.

Thus, the testimony of the ancient Greek and Roman writers on Alexander and Megasthenes in India find nothing debatable about Indian democracy. It seems evident that the 18th century doctrine of Oriental Despotism goes against the ancient sources that survive on Alexander and Megasthenes in India. The latter do not sustain the modern theme of Athens as mother of democracy. It was not the ancient Greeks and Romans who pushed this assertion, it was modern scholars of ancient Greece and Rome.

Work remaining

Much remains to be done, in the investigation of the history of democracy in India. It is not enough to show the bare existence of it in ancient India, but to examine its persistence. While evidence of it has been extended back to the Vedic period, there is a long blank space in which evidence for democratic states has not been adduced as yet.

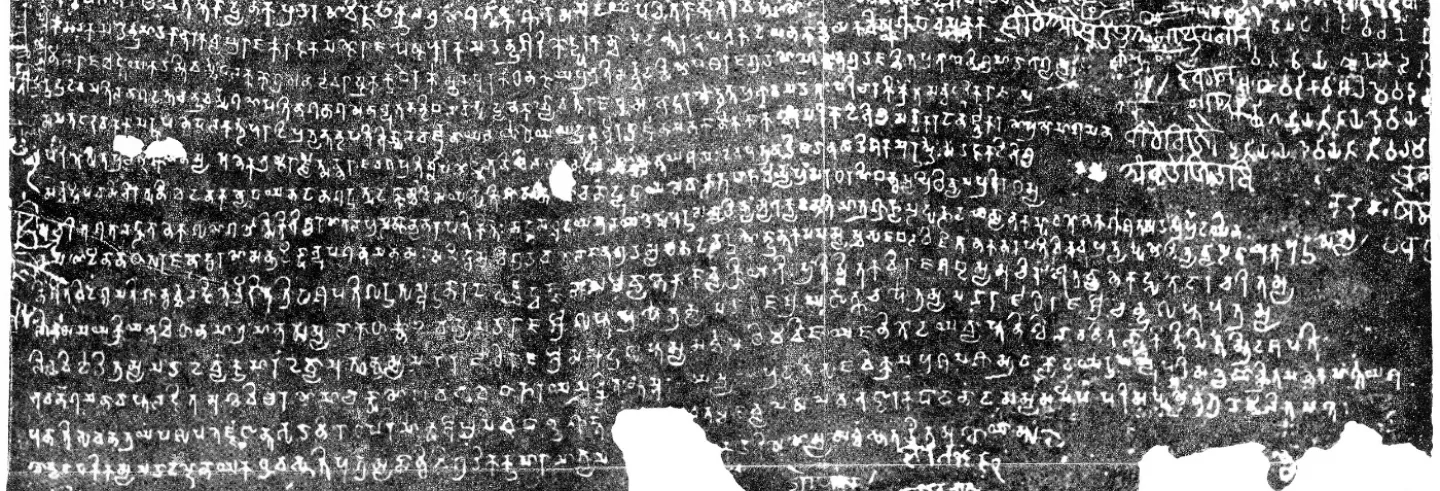

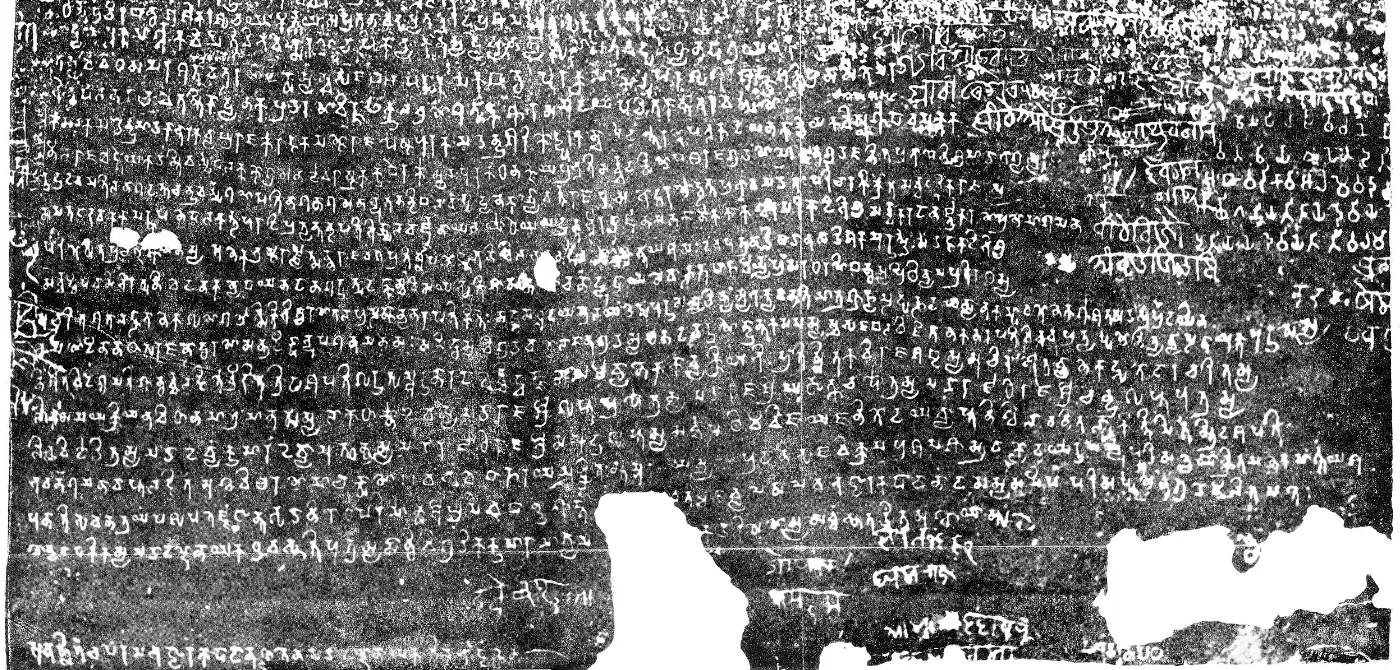

Some have thought that they faded away or evolved into kingdoms after the Gupta empire. In the Allahabad Pillar Inscription of Samudragupta, there is reference to republican states being in tributary relation to the Gupta emperor, as an ongoing relation; but many scholars have thought it marks the end of true republics. If that were so the blank space in Indian history runs from the end of the Gupta empire to the independence of India in 1947. It is all very well to celebrate the evidence for democracy in ancient India, but the programme must also look closely at this great blank space for which we have as yet found little evidence. Thus, much remains to be done on the history of democracy in India.

At the same time, much remains to be done on the world history of democracy before we can determine India’s place in this process. There is an international collaboration in train, a three-volume worldwide overview, The Cambridge History of Democracy under the editorship of Markku Pentonen, which attempts to go beyond the theme that democracy begins at Athens. The project has been delayed by the spread of the Corona virus and is still in recovery. When it appears let us see how well it succeeds in finding a better way forward.

Thomas R. Trautmann is Professor Emeritus of History and Anthropology at the University of Michigan.

Professor Emeritus of History and Anthropology, University of Michigan. He is the author of Dravidian Kinship (1981); Aryans and British India (1997); Languages and Nations: the Dravidian Proof in Colonial Madras (2006); Arthashastra: The Science of Wealth (2012) and Elephants and Kings:An Environmental History (2015).