Several states in India, including Delhi, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, and Karnataka, have implemented schemes to make bus-based public transport free for women. Apart from these schemes, nearly all states in India provide concessions on public transport fares to some disadvantaged groups such as senior citizens and people with disabilities.

An independent study of the scheme in Tamil Nadu, based on a survey of 3,000 women, indicated that it enabled two-thirds of the women to save more than Rs. 400 a month, which they primarily spent on household needs, food, education, and healthcare, demonstrating how free public transport is directly linked to family welfare and enlarging the social safety of its members (Narayanan 2023). Yet, critics of such schemes argue that they are intended to lure voters with short-term benefits and are fiscally irresponsible. The debate over “freebies” in public transport policy often centres on their perceived role as tools for political appeasement rather than as instruments of substantive social change. The case of Delhi’s free bus travel scheme for women offers a compelling counterpoint.

Unsurprisingly, we found that the scheme has significantly improved women’s access and made it possible for a significant number of them to go out independently, which they earlier could not do.

As the scheme launched in October 2019 completed five years in the National Capital Region, which comprises Delhi and some surrounding districts of Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan, we conducted an evidence-based analysis to understand how it has impacted women’s mobility in the area. Unsurprisingly, we found that the scheme has significantly improved women’s access and made it possible for a significant number of them to go out independently, which they earlier could not do. This challenges the notion that making public goods and services free to users is merely a populist measure that hurts development.

For women in urban India, mobility is often constrained by safety concerns, unreliable services, and cultural norms that discourage independent travel (Mehta and Sai 2021). While fare-free schemes address the financial barrier to mobility, their true impact lies in their potential to empower women by making the city more accessible. This article examines the findings from a study of Delhi’s free bus travel scheme, highlighting its direct and spillover benefits for women’s mobility and social participation. Some of these findings were earlier presented in the form of a report jointly published by the Public Transport Forum and Greenpeace India.

Free Public Transport

The term “freebie” often carries a negative connotation, implying a wasteful use of public resources to win political favour. However, when applied to essential public goods such as transport, such schemes can have far-reaching and universal benefits. Public transport should be seen as more than just a means of getting from one place to another; it is a gateway to education, work, healthcare, and civic life. For women, in particular, who often face additional constraints on their mobility due to patriarchal norms and lack of access to necessary means, free public transport can be a powerful tool for improving their capability.

Delhi’s bus travel scheme allows women to travel free of cost on all buses operated by the Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC) and the Delhi Integrated Multimodal Transport System (DIMTS). Unlike similar initiatives in other states, the scheme is universal, with no restrictions based on income, occupation, or residence. This universality ensures that all women, regardless of their socio-economic background, can benefit from the policy.

Methodology

The study draws on 510 survey responses and 20 in-depth interviews conducted across Delhi to assess the impact of the fare-free bus travel scheme. We employed purposive sampling to select interviewees, ensuring diversity in age, caste, religion, and employment. The interview data was recorded, transcribed, and coded to identify key themes, which informed the design of a structured questionnaire.

The findings reveal significant changes in women’s travel patterns, economic behaviour, and social participation, which we have used to emphasise the broader implications of free public transport for women in Indian cities.

The survey included four main sections—General Information, Benefits of Bus Use, Challenges in Bus Use, and Suggestions for Reform—and additional sections for persons with disabilities and non-users of public transport. A quota-based sampling strategy was adopted to align with the study’s scope and resource constraints. Field surveys focused on bus users, sampling 50 of Delhi’s busiest bus-stops based on boarding volume, while an online survey was open to all Delhi-based women.

Respondents were recruited on-site, ensuring diversity in gender, age, and physical ability, and included daily wage workers, students, working women, senior citizens, and transgender individuals. The survey was conducted in person across spatially and demographically diverse Delhi localities such as Seemapuri, Mayur Vihar, and Dwarka. A raking-based weighting technique was used to improve the sample’s representativeness of the population.

Findings in Delhi

The findings reveal significant changes in women’s travel patterns, economic behaviour, and social participation, which we have used to emphasise the broader implications of free public transport for women in Indian cities.

The most immediate impact of the “pink ticket” scheme, as it is popularly known, has been a substantial increase in women’s bus ridership. Official data shows that women’s share of bus ridership rose from 25% in 2020–21 to 33% in 2022–23. Survey results indicate that 23% of women increased their frequency of bus travel after the scheme’s introduction, while 15% of women who rarely or never used buses before the scheme now use them regularly. This suggests that the policy has not only encouraged existing users to travel more frequently but also attracted new users who were previously excluded due to cost barriers.

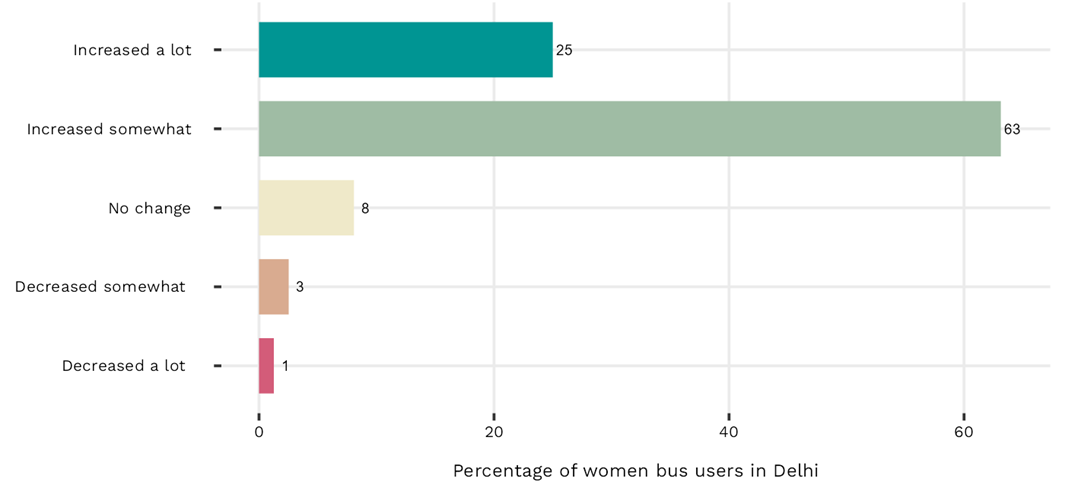

Aparna, a homemaker who began traveling more frequently after the introduction of the free bus travel scheme said, “I can take different routes and switch between modes to go anywhere. This is one great advantage of free buses. Earlier, I wasn’t confident travelling alone, but I’ve learned to do so now.” Going by the perception of respondents, 88% of women bus users feel that the scheme has helped them use buses more (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Change in Bus Use among Women after Launch of Pink Ticket Scheme

Spillover Effects

The bus travel scheme has had far-reaching economic and social benefits for women in Delhi. For low-income women, the savings from free travel have been redirected towards household expenses, children’s education, and healthcare. A significant portion of surveyed women, 54%, reported saving money for future use or for spending on household items. Half of them set aside money as emergency funds, while one in three of them used the savings to buy personal items they otherwise could not afford.

Around 15% of women who use buses are now able to allocate more funds towards health and education. School and college-going girls, in particular, spend less when they choose buses, saving the money for future needs or using it to purchase food, books, grooming products, or other personal items for which they might not receive money from their families. Mothers often use the money saved for their children or emergencies. A factory worker and mother of three daughters explained to us that she encourages her children to take the bus by reminding them that the savings could be used for treats such as juices and snacks.

Figure 2: How Women Use the Savings from Free Bus Travel

The scheme has also enabled women to explore new opportunities. For instance, some women took up jobs or educational courses that were previously unaffordable due to travel costs. Others reported using buses for leisure activities, such as visiting parks, temples, or family members, which were once considered luxuries.

More independence and confidence

One of the most transformative impacts of the scheme has been its effect on women’s independence and confidence. Survey data shows that two in three women feel more independent about going around the city since the scheme’s introduction. Many women reported gaining the confidence to navigate the city on their own, learning bus routes, and dealing with challenges such as overcrowding or harassment.

Beyond the Freebie Debate

Delhi’s fare-free bus travel scheme challenges the simplistic “freebie” narrative by addressing deeper structural barriers to women’s mobility, including unpaid care work. Unpaid care work remains invisible and undervalued, and represents lost wages (Federici 2020). It also represents the additional time lost because of walking and waiting for public transport. By removing financial barriers, the scheme has allowed women to reclaim time typically spent on care giving, redirecting it toward education, employment, healthcare, and leisure. This shift enhances women’s individual agency while also disrupting the gendered division of labour and creating opportunities for making women’s socio-economic participation more visible and empowered.

By making public transport accessible, the pink ticket scheme in Delhi has enabled women to reclaim time, expand the opportunities they have access to, and challenge entrenched gender norms.

Yet, the scheme’s success underscores the persistent inequities in women’s mobility. Time-geographical constraints, such as the need to balance care-giving with limited travel windows, remain a significant challenge, particularly for low-income women. Safety concerns, the higher cost of trip chaining, and inadequate infrastructure further compound these issues. Women who responded to our survey reported that poorly lit bus-stops, long waiting times, and the risk of sexual harassment deter women from using public transport, especially after dark.

Looking Forward

To maximise the impact of such schemes, policymakers must adopt a more comprehensive and integrated approach. Investments in urban transport must be made gender just with a commitment to prioritise gender-sensitive urban design. It may include improving the frequency of buses to reduce the wait time at bus-stops, real-time tracking on all routes and the display of information at bus-stops, and women-only buses during peak hours.

Since the most typical lengths of trips women make for everyday needs are short (less than 1-2 km), expanding the scheme to include last-mile connectivity options such as free e-rickshaws or mini bus services can address the time-geographical constraints faced by women, particularly those in peripheral areas. As in Delhi, such schemes should cover all kinds of bus services (AC, non-AC, premium) to decrease the waiting time and make travel easier for the beneficiaries.

The idea of including the metro railway under such a scheme could make it more affordable and boost ridership (Tiwari and Jain 2023), which remains alarmingly low in all the functional metro systems in the county. In addition, public awareness campaigns and more women in the transport labour force can challenge cultural biases and promote gender sensitisation in public spaces, which is crucial for fostering a more inclusive transport ecosystem.

Delhi’s fare-free bus travel scheme is a transformative policy that offers more than mere appeasement of women for electoral gains. Rather, we argue that it provides a template for similar state-level schemes to address unpaid care work, time poverty, and mobility inequities in all urban settings. By making public transport accessible, the pink ticket scheme in Delhi has enabled women to reclaim time, expand the opportunities they have access to, and challenge entrenched gender norms.

However, its full potential depends on complementary measures that tackle safety, infrastructure, and cultural barriers. When designed under a gender-equity lens, free public transport can become a catalyst for inclusive urban development, transforming cities into spaces where women can move freely, safely, and with dignity. A free ticket, for many women, is a ticket to freedom—a step towards addressing the systemic inequalities under patriarchy that constrain their social lives.

Nishant coordinates the Public Transport Forum, India, and his research on mobility and transport justice bridges academia and activism, engaging with civil society and social movement groups.

Archana Singh is a PhD student at Pennsylvania State University, and her current research focuses on understanding the spatialities of young women’s leisure experiences in Lucknow.