Introduction

India’s digital platform-based food delivery sector has greatly enhanced the visibility and reach of restaurants and improved consumers’ choices and convenience. These platforms have now ventured into selling their own fresh food, raising concerns about potential conflicts of interest and anti-competitive practices in the sector. This issue needs closer scrutiny as it has implications for the welfare of consumers and restaurants. There is also the larger question of curbing monopolistic tendencies to ensure healthy competition in digital commerce. In this connection, it is worth exploring the role and scope of the government-backed Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) initiative to promote open networks for buying and selling goods and services online.

From Goods to Food

Quick commerce has become ubiquitous in Indian cities, especially with platforms such as Zepto, Zomato (through Blinkit), and Swiggy (through Instamart) delivering groceries and other goods to homes in 10 minutes. These platforms have also extended quick deliveries to include freshly prepared food, enabling customers to access food from restaurants within a 2-kilometre radius in just 10 to 15 minutes. This race has now intensified with the Zepto Café app gaining traction last year. Unlike its rivals partnering with restaurants, Zepto undertakes in-house production of food and beverages in a designated space within its “dark stores”, making it a high-margin business.

The newly launched quick food delivery apps have minimal delivery charges while the parent food delivery apps have platform fees apart from distance-based delivery fees, which make them costlier from the consumer’s point of view.

In response, Zomato’s grocery arm Blinkit launched Bistro in December 2024 with a promise of delivering snacks, beverages, and meals from its “strategically located” kitchens in 10 minutes. Swiggy soon followed suit, introducing Snacc in January 2025, an app currently operational in select areas of Bangalore, Noida and Gurugram. Unlike Swiggy’s app for quick food delivery, Bolt, which partners with restaurants in the vicinity, Snacc operates from a central location. Restaurant owners, through the National Restaurants Association of India (NRAI), have criticised food delivery apps for selling fresh food, as this directly competes with their restaurants. The NRAI views this as a “breach of trust” by the aggregators.

Digital platforms have rich data on the food preferences of different localities collected over the years (this is unavailable to the restaurants) and can use it to their advantage when setting up food production units to cater to different areas. Moreover, the newly launched quick food delivery apps have minimal delivery charges while the parent food delivery apps have platform fees apart from distance-based delivery fees, which make them costlier from the consumer’s point of view. The NRAI plans to approach the Competition Commission of India (CCI) to complain about “private labelling” by Zomato and Swiggy through Bistro and Snacc.

Power Dynamics

The root of the problem is that the market is dominated by two food aggregator platforms, which leads to unequal power relations between them and their restaurant partners. The food delivery space is a duopoly, with Zomato and Swiggy commanding close to 95% of the market share. Additionally, price parity clauses in the agreements between platforms and their restaurant partners ensure that the latter cannot charge different prices on different platforms. This curbs competition between platforms and reduces the bargaining power of restaurants.

The tight race between the digital platforms to capture market share has led to a situation where their innovations and business decisions mirror each other, as can be seen from the launch of their new applications. This means that restaurants do not have the option of switching to a “more conducive” platform. The only other possibility is to deliver their food on their own, which would require a huge investment. This can be done only if the restaurants exit the platforms because the services of restaurant discovery and food delivery are bundled on them. 1Bundling implies combining different services into a single package in such a way that one cannot be chosen without the other(s).

There is also the larger question of whether a marketplace should be allowed to be a market participant as well. There is no law that prohibits this. Many of the popular retail supermarkets in India sell products under their own labels that directly compete with those from fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies. The problem arises when the marketplace is almost fully dominated by two brands, which makes it prone to abuse. While there is a limit to the market share that can be captured in physical markets because of space and size constraints, there is no such limit in the digital domain.

Reports suggest that … [an] inquiry by the CCI’s Director General found food delivery platforms to be indulging in anti-competitive practices, including preferential treatment of some of their restaurant partners.

Though dominance is not disallowed by the Competition Act of 2002, the abuse of dominance is. In a 2022 complaint by the NRAI to the CCI against food delivery platforms, the anti-trust regulator took note of the conflict of interest in the platforms operating as a marketplace while simultaneously having their own private brands/ entities which they “may be incentivised to favour”. Reports suggest that the subsequent inquiry by the CCI’s Director General found food delivery platforms to be indulging in anti-competitive practices, including preferential treatment of some of their restaurant partners. The final order of the regulator is yet to be released.

Data Sharing

Food aggregators being allowed to produce and sell cheaper items of their own may be advantageous to consumers and may also encourage restaurants to streamline their processes to improve efficiency and reduce costs. However, the information asymmetry in the market needs to be addressed. Bistro and Snacc may be able to access the data on consumer demand collected by their parent organisations. To keep the playing field level and maintain the trust of their restaurant partners, the digital platforms should be mandated to share consumer data with their restaurant partners.

The preferential treatment of restaurants through algorithmic management of listing, pricing, and discounts should also be curtailed through regulation to create open and inclusive spaces that promote healthy competition. Moreover, if the new applications are selling privately labelled fresh food and competing with restaurants, their food production business should be legally treated on a par with restaurants, making hygiene and quality control requirements mandatory for them.

Need to Create Alternatives

According to the Statista website, India’s online food delivery market, which was worth US$7.4 billion (Rs. 63,640 crore) in 2023, is expected to grow more than three times to reach US$24 billion (Rs. 206,400 crore) by 2026. Hence, as a long-term strategy, it is important to create alternative platforms that can ensure a competitive market structure in the food delivery segment. Network externalities benefit the early movers in the food delivery sector, making it harder for new players to enter the market. 2The value or benefit that a user derives from the service is dependent on the number of users in the network. If there are many customers using a particular platform, restaurants would prefer to be listed on that platform.

In such a scenario, the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC), promoted by the Government of India offers retailers a possible alternative. The ONDC’s commissions are only about a fourth of that of the dominant food delivery platforms.

The ONDC is often described as a disruptor in India’s digital commerce ecosystem because it provides users an alternative to the present platform-centric model. ONDC hosts multiple seller and buyer applications and logistics providers under the same umbrella and allows them to transact with each other. It currently hosts 13 domains, ranging from food and beverages to mobility and financial services.

Since its inception in April 2022, the ONDC has subsidised transactions on the platform through discounts in packaging and delivery fees in a bid to expand the network.

The food and beverages portal allows restaurants to directly sell food to consumers through buyer apps, thereby increasing their margins and decreasing food prices for customers. Emergent food delivery platforms such as Magicpin and Ola Consumer have been using the ONDC platform to make inroads into the food delivery segment. Though the ONDC provides services in more than 616 locations, its popularity is largely restricted to a few metropolitan cities. The data indicates that in March 2025, about 25% of all the orders in the retail segment were from only three districts—Bengaluru Urban, Gurugram, and Gautam Buddha Nagar.

Since its inception in April 2022, the ONDC has subsidised transactions on the platform through discounts in packaging and delivery fees (in addition to offers given by seller/buyer apps) in a bid to expand the network. However, a report by an equity research firm in March 2023 argues that the ONDC would become unsustainable once it withdraws the financial support provided to its partner apps. Without the ONDC’s discounts, these applications would have to increase commissions from restaurants to cover their delivery charges, which in turn would mean higher prices for customers.

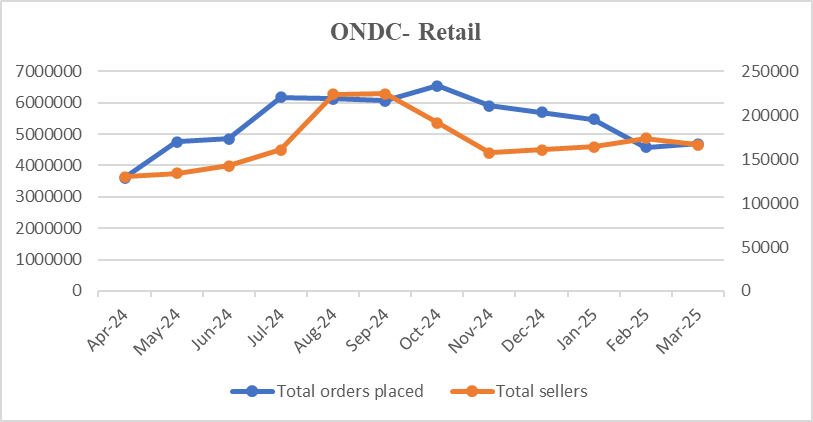

Figure 1: Orders and Sellers on ONDC - Retail Segment

Significantly, reports suggest that when the ONDC began cutting back some of its discounts in May 2023 and introduced a packaging fee and a nominal delivery charge for repeat customers, its transaction volume saw a sudden drop. When the ONDC drastically cut back on its financial incentives to its partners in July 2024, transactions in the retail segment declined to 46 lakhs in February 2025 from its peak of 65 lakhs the previous year. The ONDC’s decision to levy a service fee of Rs. 1.50 per transaction on orders greater than Rs. 250 from January 2025 onwards is further expected to impact its transaction volume.

Figure 1 shows the monthly orders placed by customers on the ONDC platform in the last one year and the total number of sellers registered on it. It clearly indicates a decline in the network’s adoption after the tightening of subsidies. 3Though the ONDC’s retail segment has seen a declining trend in both number of orders and registered sellers in recent months, monthly network orders of all domains together had increased significantly from 72.6 lakhs in April 2024 to 161.4 lakhs in March 2025. This was largely due to the steady growth of the mobility and logistics segments (see https://opendata.ondc.org/). While the retail sector of the ONDC (which includes multiple domains apart from food and beverages) is not comparable to Swiggy and Zomato (whose primary service is food and grocery delivery), we examine the business to consumer (B2C) performance of these companies in the last few quarters to understand whether the decline in adoption is a systemic issue.

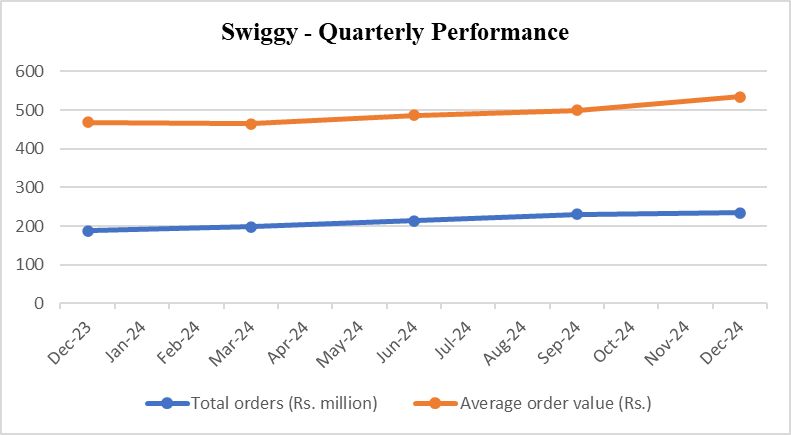

Figure 2: Swiggy - Quarterly Orders and Average Order Value

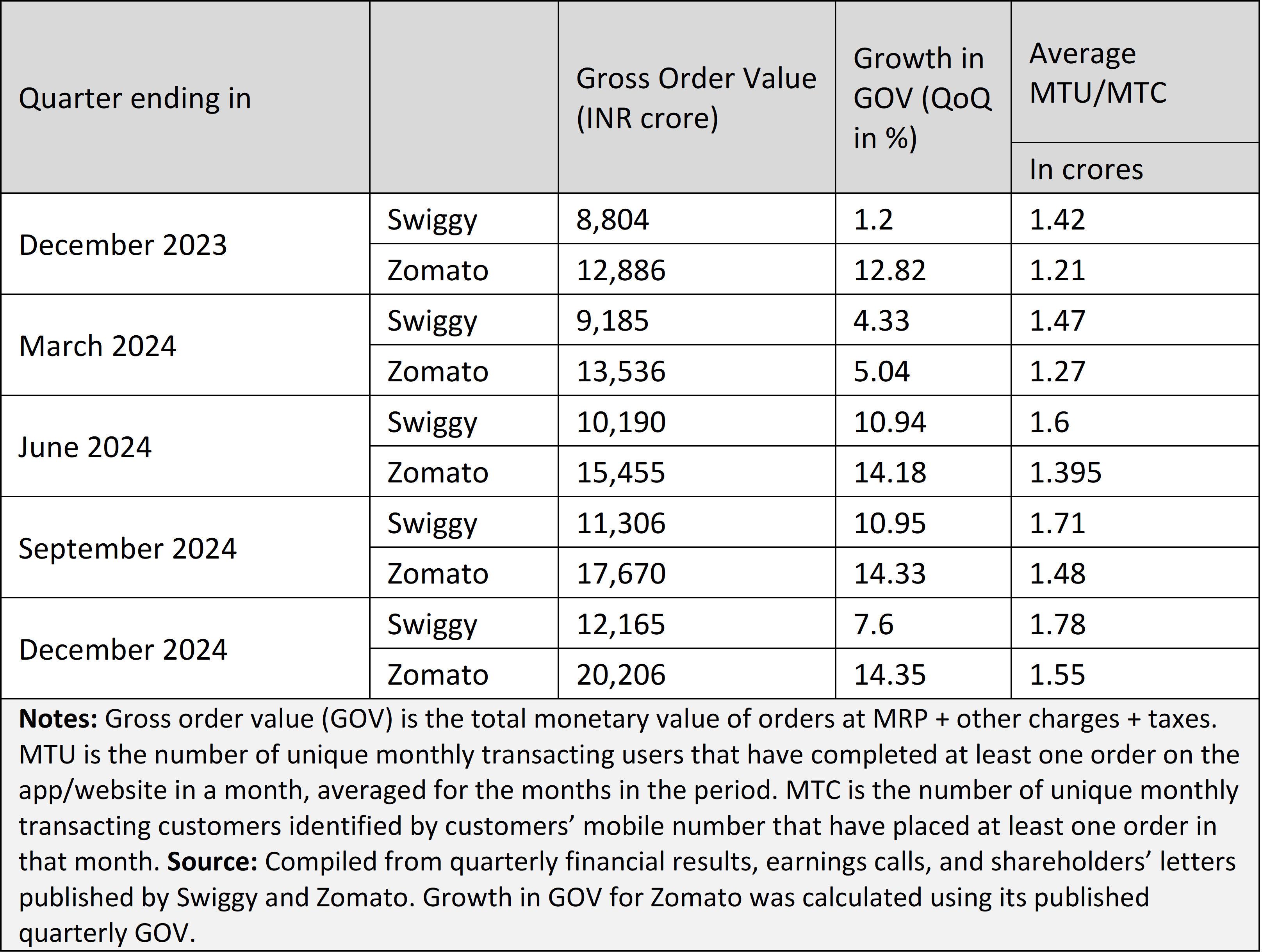

Table 1: Quarterly Performance of Swiggy and Zomato (Dec 2023 – Dec 2024)

Figure 2 illustrates the total orders and average order value (AOV) in Swiggy’s business to consumer segment (unavailable for Zomato) in the last five quarters (monthly data was unavailable). There is a perceptible increase in the number of orders or the average order value of Swiggy in recent months. Table 1 shows the gross order value, growth in gross order value, and average monthly transacting users or customers of Swiggy and Zomato. It may be observed that both gross order value and average monthly transacting users and customers have been steadily increasing for both the companies. Both these venture capital-backed platforms have been moving closer to profitability, and Zomato has already achieved it.

The ONDC cannot become a bulwark against monopolistic tendencies in the online food delivery sector unless it is able to attract a greater number of customers and sellers. While its initial discounts have helped kick start traffic on the platform, the withdrawal of incentives has affected its volume of transactions and the survival of partner applications. Another concern is the opacity surrounding the funding of its discounts. It also suffers from issues in facilitating returns and quality control because of its interoperable nature, which is the opposite of the “walled garden” model followed by Swiggy and Zomato.

To compete with platforms backed by investors with deep pockets and stay true to its objective of democratising digital commerce, the ONDC should attempt to provide food at a lower price point than the existing platforms. It can achieve this by providing targeted subsidies until it builds a substantial, loyal customer network; by onboarding home cooks, cloud kitchens, and neighbourhood cafes to offer fast, affordable food delivery; and by forging partnerships with wholesalers, retailers, and new market entrants.

While it is important for the government to encourage innovation and enable these firms to function without constraints, it is equally relevant to create a level playing field and promote healthy competition.

Expanding into tier 3 and 4 cities where the platforms do not have a significant presence is also a good strategy. Bringing in popular restaurant chains—Domino’s, for example, which joined last year—and supporting the growth of partner apps is crucial. In response to Bistro and Snacc, the NRAI has decided to boost its presence on the ONDC to challenge dominant food aggregators and emerge as a strong third force.

Conclusions

Much credit needs to be given to food aggregator and delivery platforms for creating a sprawling market for their services in India. However, like many platform-based markets that benefit from network externalities, the market is now in the hands of very few players. This tilts the balance of power between the digital platform and other participants in favour of the former while also creating entry barriers for newcomers.

Digital platforms take significantly less time to attain market dominance because venture capital-backed companies can grow without revenue constraints and scale up quickly. While it is important for the government to encourage innovation and enable these firms to function without constraints, it is equally relevant to create a level playing field and promote healthy competition. This requires a tightrope walk that uses both regulation and the creation of democratic digital spaces such as the ONDC. However, to make the ONDC effective, greater efforts must be made to increase its adoption and expand its network.