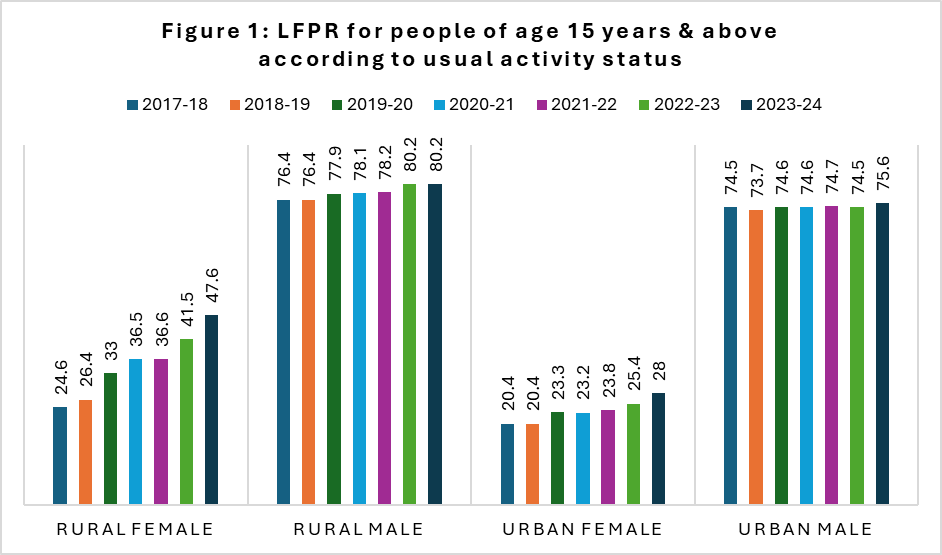

For the past few decades, India has seen low and declining female labour force (LFPR) and work force participation rates (WPR). Since 2017, there has been some reversal in the trends, showing a rising trend of LFPR (Figure 1) and WPR (Figure 2).

The rise has been sharper since 2022 (the post-Covid-19 years). The increase in the LFPR in 2022-23 could be due to the easing of the economy from Covid-19 restrictions. Besides, a part of the rise in the LFPR could also be due to the prevailing distress in the labour markets caused by job losses or a fall in income during the Covid-19 period (2020-2022).

Once the economy overcame those restrictions, many people who were not part of the labour force likely started looking for jobs to supplement their family incomes. So, in 2022-23, all categories of workers (male and female, both in rural and urban areas) witnessed a rise in the LFPR.

The latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), for 2023-24, conducted by the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) shows a continuation of these trends for females. The LFPR of rural women increased by 6.1 percentage points, and for urban women, it increased by 2.6 percentage points in 2023-24 over the previous year. Since the LFPR of men remained the same in rural areas and increased only marginally in urban areas in the same year, this rise in female LFPR in rural and urban areas seems more gender-specific.

A deeper analysis is necessary to make sense of this data.

Change in Methodology

There have been some changes in the definition of the workforce in the 2023-24 PLFS for those mainly engaged in self-employment activities.

The PLFS defines self-employed workers as those who operate their own farm or non-farm enterprises or are engaged independently in a profession or trade on own-account or with one or a few partners. Two broad changes in definitions in 2023-24 are worth mentioning here.

First, there has been a direct change in the methodology of identification of two major categories of persons engaged in domestic duties, mentioned in the ‘Instructions to Field Staff’ (NSSO, 2023a, pp. C-56—C-58) and ‘Note on Updated Instruction to Field Staff of Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) for July 2023 to June 2024’ (NSSO, 2023b, p. 1).

In a new definition, if a household member is engaged in domestic duties according to the major time criteria but also engaged in a free collection of firewood, vegetables, etc., for own use for 1 or 2 hours regularly or at least 30 days during the preceding 365 days, then the usual principal activity of the person will be Activity Code 92 (domestic duties). However, the person will be considered to have a subsidiary economic activity and will be considered self-employed (Activity Code 11). Therefore, they will be considered self-employed going by their usual status (principal and subsidiary), while in earlier surveys, these persons were considered ‘not in the labour force’ and likely recorded under Activity Code 93 (engaged in domestic duties and free collection of goods for household use).

As the LFPR is the sum of WPR and unemployed and excludes those ‘not in the labour force’, a shift from 'not in the labour force' to inclusion in the workforce due to the change in definition would undoubtedly increase the LFPR. Since the collection of food, fuel, etc., in India is disproportionately done by females, the rise in the number of females in the self-employment category (therefore in the LFPR) in 2023-24 is likely due to the change in definition.

Second, the 2023-24 ‘Instructions to Field Staff’ survey document (NSSO, 2023a, p. C-56), for the first time, includes two new economic activities performed predominantly in a self-employed t capacity, for which special care has to be taken to identify whether or not a person is working.

The two new economic activities listed are:

(i) In situations where one household member (say, the wife) prepares papad, muri but another household member (say the husband) sells such goods, both of the household members (the husband and wife in this example) will be considered engaged in economic activity.

(ii) Working in kitchen gardens, orchards, household poultry, dairy, free collection of fish, small game, wild fruits, vegetables, etc., for household consumption/sale

It is likely that both these activities in earlier surveys were not counted as economic activities and are now put under self-employment. Such activities, even for self-consumption, are now included as full economic activities based on the time criteria. Thus, there is the possibility that a section of workers (primarily female workers) who were earlier recorded as having domestic duties and therefore identified as 'not in the labour force' are now categorized as self-employed according to the usual activity status.

Thus, both these definitional changes are likely to shift workers from ‘not in the labour force’ to primarily self-employed. Given the nature of occupation segregation between men and women in India, this change in categorisation would have a disproportionately greater impact on the labour force distribution of women, and more so in the rural areas.

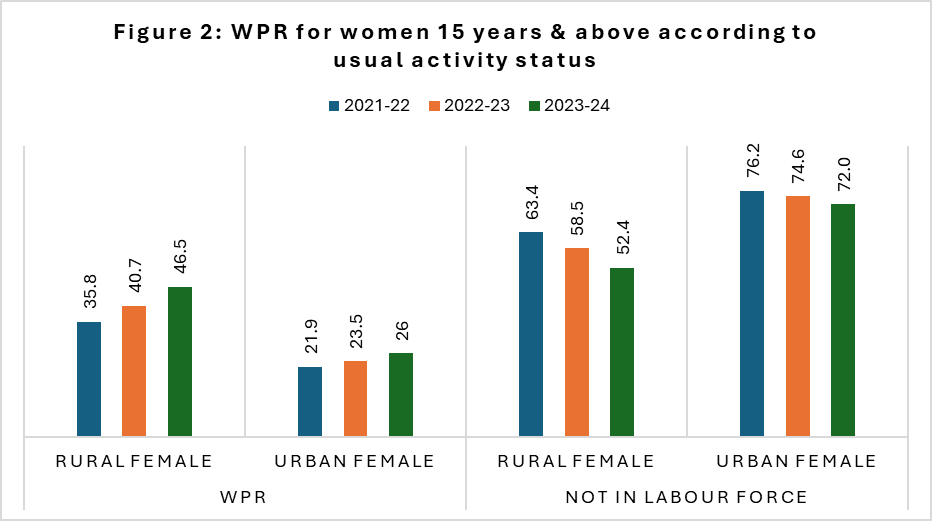

Figure 2 confirms that the rise in the share of WPR with a commensurate fall in the share of ‘not in the labour force’ for the female category in rural and urban areas has been substantial during the last year, with as expected, changes being comparatively higher in rural areas.

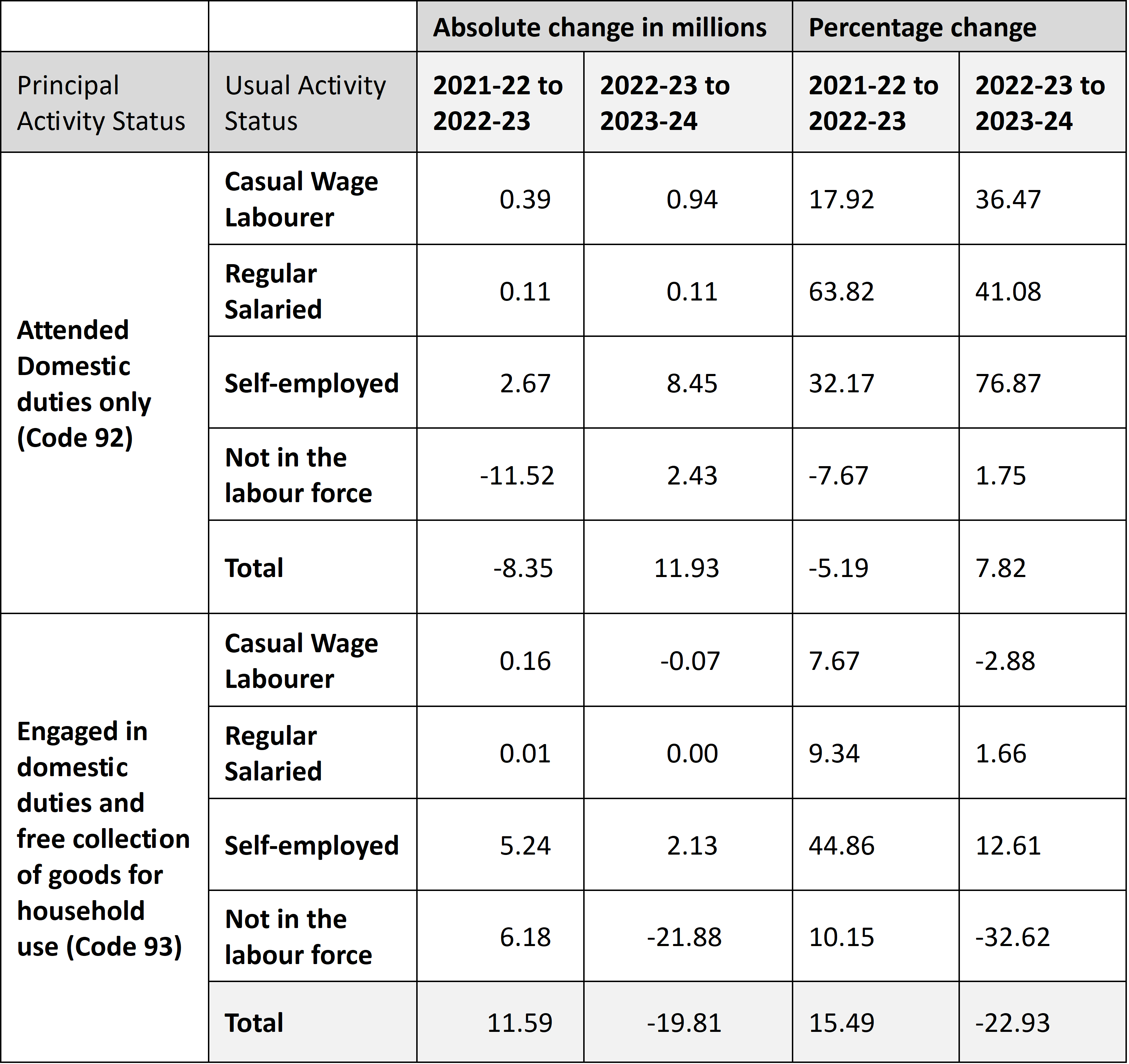

Table 1: Structure of change within the activity codes 92 (domestic duties) and 93 (domestic duties and free collection of goods for household use) of female workers

Further, as discussed earlier, the change in definition is likely to shift a sizable number of workers who were earlier categorized as domestic workers who were carrying out free collection of goods for household use (recorded as principal status activity Code 93) to workers with a domestic duty (according to principal status Activity Code 92) and on the subsidiary activity basis to self-employment (Code 11). Those workers could now be shifted from ‘not in the labour force’ to being self-employed.

Table 1 reflects that there has been a significant fall (of around 19.81 million) in the absolute number of female workers recorded under Code 93 in the latest survey. It is important to note that the total rise in the WPR for women in 2023-24 , in both rural and urban areas, was nearly 18 million. In contrast, Code 92 alone witnessed a rise in female workers by nearly 12 million in 2022-23. This further supports the possibility of a large pool of female workers having been shifted from Code 93 to Code 92 due to a definitional change. Further, within principal activity Code 92 (domestic workers), a substantial rise was witnessed in 2023-24 in the number of female workers with subsidiary self-employment status (to nearly 8.5 million). It shows a significant rise in the growth rate of workers categorized as ‘engaged in domestic duties’ on a principal activity basis, while on a subsidiary basis (therefore also on the usual activity basis), they are categorized as self-employed.

The growth of self-employment among workers with domestic duties increased by nearly 77 per cent during 2023-24 compared to around 32 per cent in 2022-23. Besides, out of the total rise in the absolute number of female workers in Activity Code 92 during 2023-24, nearly 71 per cent were categorized as self-employed on a subsidiary basis. Therefore, they were recorded as self-employed on the usual status basis in 2023-24 PLFS data. Many of these workers are likely categorized as self-employed due to the change in the definition in the latest survey.

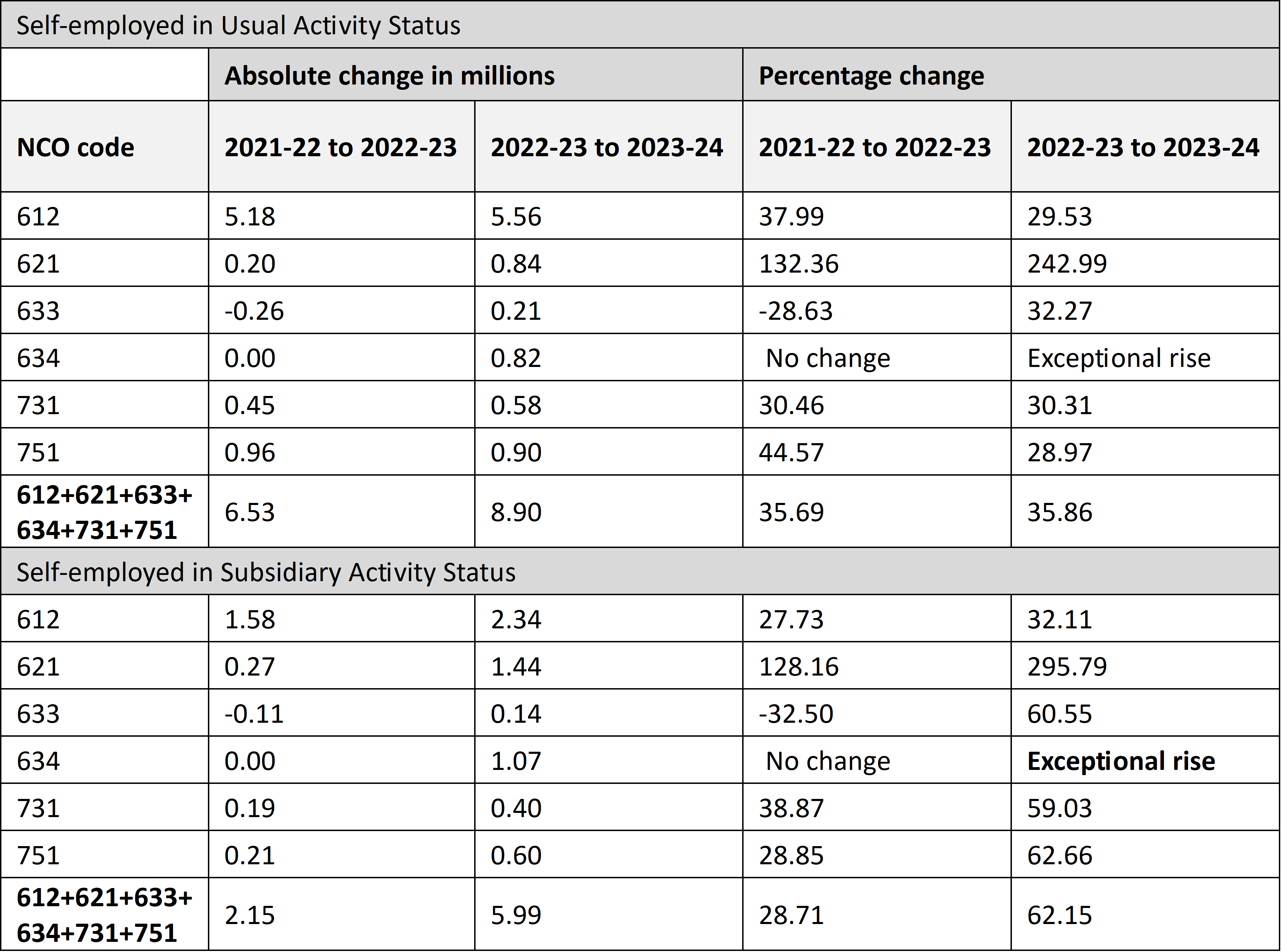

Though it is difficult to quantify how precisely the recording of labour in different activities changed due to changes in the definition, as well as the extra care and precision that may have been taken in the new survey, a brief analysis of the changes in the different related occupations of workers in 2023-24 would give us some idea. The National Classification of Occupation (NCO 2015) codifies the different occupation types of workers in India. Since the PLFS only records three-digit NCO codes (only a broad classification of occupations), it is difficult to identify the change in occupation based strictly on the change in instructions or definition of the workers.

Table 2: Change in categorization of women with NCO codes as per usual and subsidiary activity status

To track the methodological change in the latest PLFS survey, women categorized in the following occupational codes are compiled and analyzed separately, according to both usual and subsidiary activity status. These NCO codes are: 612: animal producers, 621: forestry and related works (includes occupations like gatherer, firewood, lac, and medicinal herbs), 632: subsistence livestock farmers, and 633 is identified as “Subsistence mixed crop and livestock farmers grow and harvest field or tree and shrub crops, vegetables and fruit, gather wild fruits, medicinal and other plants, tend or hunt animals, and/or catch fish and gather various forms of aquatic life to provide food, shelter and a minimum of cash income for themselves and their households.”

Similarly, code 634 is identified as “Subsistence fishers, hunters, trappers and gatherers gather wild fruits, medicinal and other plants, hunt and trap animals, catch fish and gather various forms of aquatic life to provide food, shelter and a minimum of cash income for themselves and their households.”; 731 includes handicraft workers; and 751 includes food processing and related trade workers (Directorate General of Employment, 2015, pp. 138-141).

Occupational code 621 is likely to capture the definitional change leading to a shift of workers from domestic duties with a collection of free goods to self-employment. It is clear from Table 2 that a rise of nearly 1.44 million female workers was recorded on a subsidiary basis during 2023-24 witnessing a growth of around 300 per cent over the previous year . As mentioned in the new document, the other occupational codes mentioned in Table 2 will likely capture the change due to the instruction to take extra care in enumeration. The combined estimate of women workers according to the usual activity status for NCO codes 612, 621, 633, 634, 731, and 751 showed a substantial rise of nearly 9 million female workers between 2022-23 and 2023-24. 1It is important to note that even a more significant change is likely in activities related to food processing; however, too many occupational codes record food processing activities. Thus, it is not feasible to identify the total change in food processing activities (we have taken just one such code, 751, for the analysis) with three-digit occupational code categories due to methodological limitations. Moreover, even these codes mentioned here are not exhaustive activities affected by the change in instruction and definition, leading to the possibility of much higher change in these categories due to methodological change.

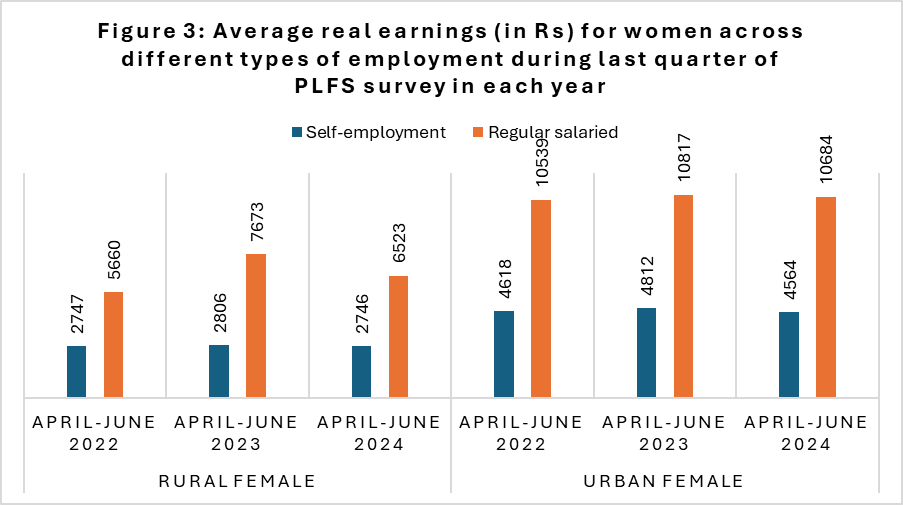

The argument that a substantial part of the rise in WPR for females happened due to definitional change rather than due to the creation of additional remunerative jobs is further substantiated by the fact that the average earnings of female workers under the self-employed category, which increased from 2022 to 2023 (Figure 3), witnessed a visible fall during 2023-24. Such a trend is also observed for regular-wage employment. The fall in the real income of female workers refutes the claim of rising employment opportunities as a factor in the increase in the WPR and LFPR for female workers in recent years and further substantiates the argument that it is the change in the definition that has mainly catalyzed such changes.

Thus, while the rise in the LFPR and WPR for females in India has been recognized as a positive change, it is essential to establish that such changes reflect concrete reality. If such changes happen due to definitional modifications, there is nothing to celebrate. Instead, it overestimates the impact of the economic policies and factors that are supposed to positively impact female labour force participation. One needs to be careful while taking the recent rise in LFPR for females in both rural and urban areas as an indicator of change, without first disentangling the role played by a change in definitions and classification of workers.

Avanindra Nath Thakur is Professor of Economics at O. P. Jindal Global University and Priyanshi Chaudhary is a research Research Scholar at O. P. Jindal Global University.