The potential of government jobs or public employment in India has received substantial public attention against the backdrop of the unemployment crisis in the country. 1The term “public employment” is being used loosely to include all those who are formally engaged with the government and getting paid for it, with specific responsibilities for carrying forward government schemes or departmental work irrespective of what their employment status is. Newspapers regularly report instances of applications from lakhs of young people, many overqualified, for a few government posts. Across the country, a large number of young students spend many of their prime years preparing for competitive exams to get into government services, all the while aware that the odds are stacked against them.

The union government has announced plans to fill vacant posts in a “mission mode”, and “rozgar melas” have been held in different parts of the country where appointment letters have been handed out to new recruits, some directly by the Prime Minister. Filling vacant government posts (up to 30 lakh under the central government), regularising contractual positions, and doubling the number of anganwadi workers were some of the poll promises of the Congress party during the recently held general election.

According to data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) for 2021-22, only 6.4% of the labour force (above 15 years of age, usual status) is in public employment, or 5.2% if we do not consider casual labour in public works. 2The PLFS and the earlier National Sample Survey employment-unemployment surveys included a question on the “enterprise type” for those in the labour force. For this article, all those who reported “government/local body or public sector enterprises” as their enterprise type are counted as being in public employment. While public sector enterprises are not included in the discussion on public employment in this paper, they are still counted in the data tables since the employment-unemployment surveys did not make a distinction between the government and public sector enterprises. In 2022, where this split is available, 8.9% of men and 2.6% of women who were in public employment were employed in public sector enterprises. Although public employment is small in relation to the labour force, its size and quality has important economy-wide implications. While it is true that direct employment by the government will not solve the unemployment problem, expanded public employment can have multiple benefits (Sinha et al. 2020).

The World Economic Forum estimates that 40% of projected job opportunities during this decade in new emerging sectors will be in the care sector. In most countries, a large proportion of care jobs are in the public sector.

To begin with, the work performed by the government is essential to keep the system running, it needs trained human resources, and not all of it can be outsourced to the private sector. In a number of areas where markets fail (due to externalities, public goods, or asymmetric information) and/or equity considerations are primary, state intervention is required in one form or the other. Government services in key social sectors such as education and health and nutrition can contribute to human development outcomes such as a reduction in maternal and child mortality, improved learning outcomes, and better nutrition, all of which contribute to higher productivity and economic growth in the long run.

They also address issues of inter-generational inequalities by expanding opportunities. Further, these sectors are relatively more labour intensive and depend on human resources for the delivery of services. Therefore, elasticity of growth of public employment is an important source of demand for labour. The World Economic Forum estimates that 40% of projected job opportunities during this decade in new emerging sectors will be in the care sector. In most countries, a large proportion of care jobs are in the public sector.

Other than providing direct social sector services, public employment is also important for the effective functioning of regulatory authorities, which can also contribute to boosting growth while ensuring protection of labour rights, preventing monopolistic profits, and keeping markets competitive. Examples include labour inspectors, extension workers in agriculture, municipal and civil engineering workers, general administrators, and so on (UN Women 2015). Increasing public employment can also contribute to the overall demand in the economy having a multiplier effect, especially in the context of poor demand.

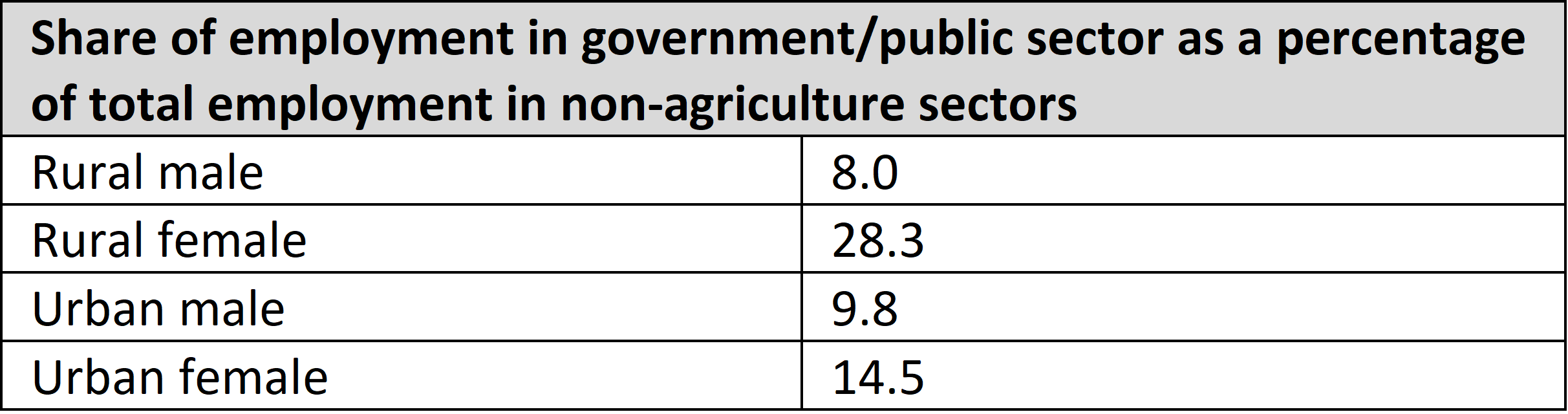

Including regular and casual wage work, 28.3% of employed women outside agriculture in rural areas are in public employment. In urban areas, the contribution of public employment to women’s employment is 14.5%.

In addition, public employment has the potential to set the minimum standards for wages, and also job benefits such as social security and paid leave in the private organised sector. Research in India has established the wage effect of public employment in the context of public work programmes such as the schemes under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) (Imbert and Papp 2015; Narayanan 2020). While there is substantial work on employment guarantee schemes, there is not much recent literature on the role of regular public employment though it has begun to figure in political discussions.

While a number of aspects to do with public employment demand further research, we draw attention to the trend of feminisation of public employment in India and highlight the need to focus not only on the quantity of jobs in the public/government sector but also their quality. The quality of jobs is important from the point of labour rights, and for public employment to deliver many of the benefits it is supposed to.

Important for Women

In India, public employment is important, especially for women in rural areas (Sinha 2022). Including regular and casual wage work, 28.3% of employed women outside agriculture in rural areas are in public employment. In urban areas, the contribution of public employment to women’s employment is 14.5% (Table 1). The contribution of public employment to men’s employment is relatively lower (8% and 9.8% in rural and urban areas, respectively) but not insignificant.

Table 1: Share of Public Employment in Total Employment in India, 2022

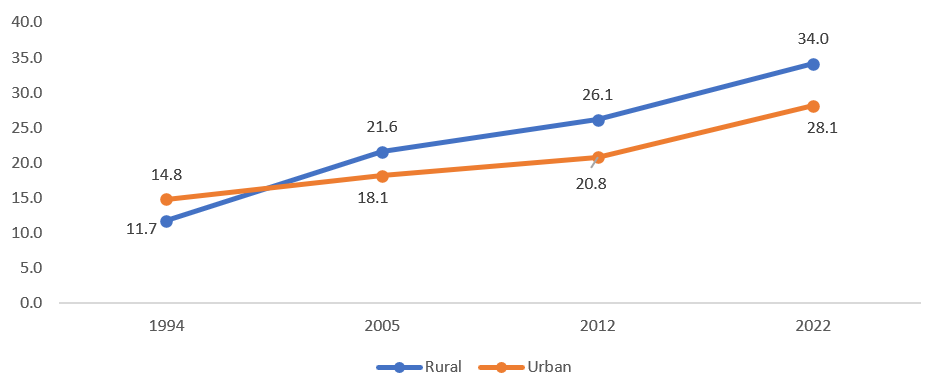

The share of public employment is even higher if we consider only “regular” employment. The PLFS surveys define “regular” employees as all those who receive salary/wages on a regular basis and hence include contractual or honorarium-based workers. 3The PLFS definition of regular wage/salaried employee includes those who work in others’ farm or non-farm enterprises (both household and non-household) and, in return, receive a salary or wages on a regular basis (that is, not on the basis of a daily or periodic renewal of the work contract). This category included not only those getting time wages but also those receiving piece wages or salary and paid apprentices, both full time and part-time. As shown in Figure 1, the share of public employment in all regular employment is quite significant, with close to a quarter of all regular employment being in the government/public sector for rural males and urban females. It is highest for rural females at 47.1%, which is also an indication of the lack of other opportunities for regular employment for rural women. Moreover, the share of public employment in regular employment has been declining for all the groups except rural females. Therefore, there has been a feminisation of public employment in India since the 1990s.

Figure 1: Share of Regular Public Employment in Total Regular Employment

Looking at the male-female ratio in public employment, it is seen that less than 12% of all regular employees in the public sector in urban areas were women in 1994. By 2022, this had increased to 28.1%. In rural areas, the share of women in regular public employment increased from about one in seven to one in three. Almost 70% of the women in regular public employment are in the feminised sectors of education, health, and social services, and an additional 18% in public administration. While men are also concentrated in these sectors, a much larger proportion (34%) is in public administration.

Figure 2: Share of Women in Regular Public Employment

Globally, it can be seen that public employment is an important source of formal wage employment for women. On average, 59% of government employees in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries are women and the overall share of women in public sector employment is higher than their share in total employment in 46 out of 64 countries (UN Women 2015). Studies have also shown that there is a high correlation between female employment in the public sector and female participation in the labour force.

India may be missing the opportunity to take advantage of the benefits that come from feminisation of public employment because the quality of public employment has been declining in tandem with the increasing share of women in it.

Further, there is also a correlation between women’s employment in the public sector and women’s overall labour market outcomes, with public employment having the potential to narrow gender wage gaps (Anghel et al. 2011; Green 2012; UN Women 2015). Public employment also offers opportunities for unionisation and collective bargaining, which could contribute to decent pay, good employment conditions, job security, and pension benefits (Rubery 2013; Sinha 2021).

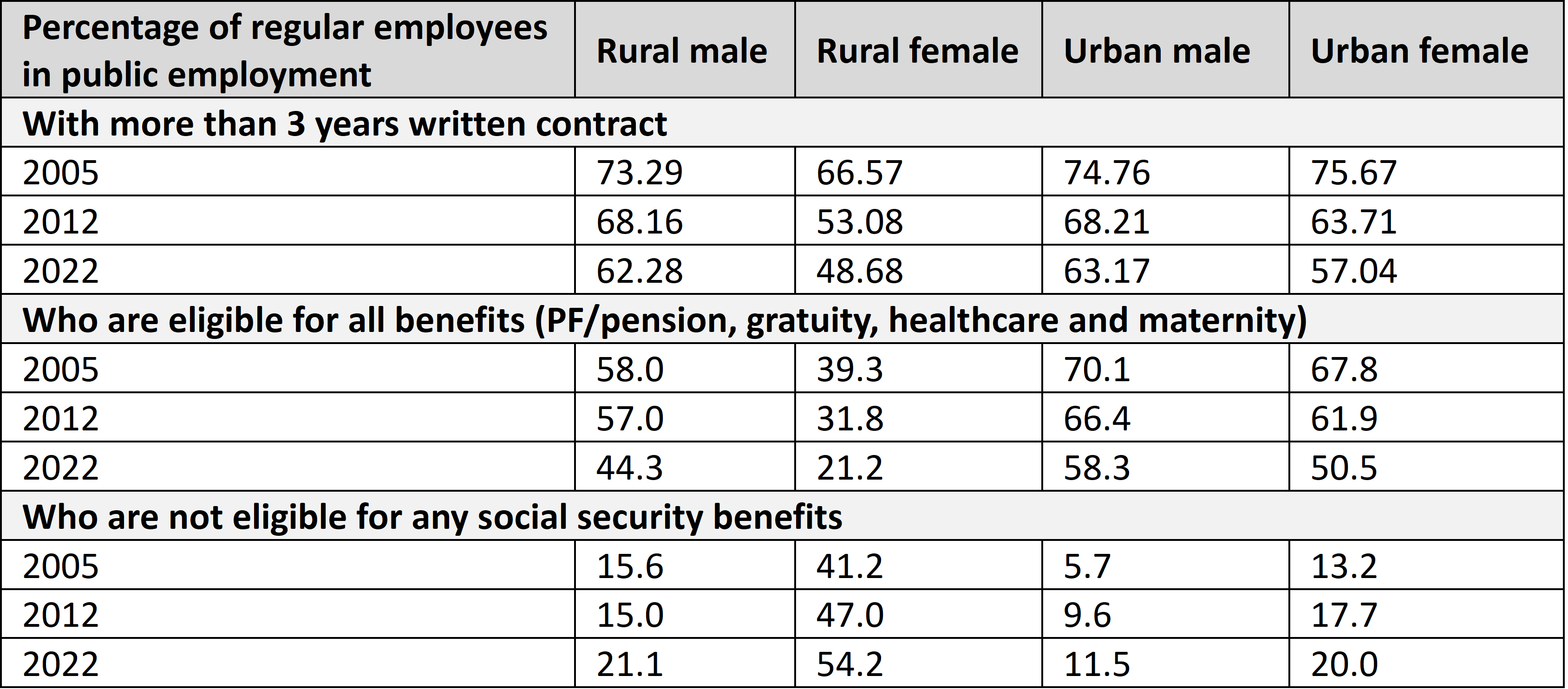

However, India may be missing the opportunity to take advantage of the benefits that come from the feminisation of public employment because the quality of public employment has been declining in tandem with the increasing share of women in it. For example, the proportion of regular government employees who reported having a written contract of more than three years duration has fallen between 2005 and 2022 (data are not available for earlier years). While fewer women compared to men have long-term written job contracts, the proportion of employees with such contracts has overall fallen. While 73% rural males and 67% rural females in regular public employment had a long-term contract in 2005, this had come down to 63% and 49%, respectively, by 2022.

Table 2: Job Conditions of Regular Employees in Public Employment

Access to social security benefits such as provident fund, pension, gratuity, healthcare, and maternity benefits through employment has also been declining. The proportion of regular government employees who report being eligible for all these benefits has come down, with fewer women compared to men being eligible (only 21% among rural women in regular public employment). In contrast, the proportion of those not eligible for any of these benefits has been increasing, with more than half the female regular public employees in rural areas not getting any social security benefits.

Feminisation of Public Jobs

Feminisation arises in basically two ways—one, when the pattern of employment shows an increasing proportion of women in jobs, and, second, when employment opportunities tend increasingly to be characterised by conditions associated historically with women’s employment. These characteristics of women’s labour include the type of contract (insecure), the form of remuneration (lower wages), the extent and forms of security provided (lower, insecure jobs), and the access to skill (again lower than those available to men). As Standing (1999: 583) puts it, “A type of job could be feminised, or men could find themselves in feminised positions.” In the case of public employment in India, both kinds of feminisation can be seen.

Such feminisation in public employment is mostly being led by the large number of women employed as frontline workers in various schemes and programmes. The oldest such cadre is of anganwadi workers and helpers under the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS). Currently, there are about 14 lakh anganwadi centres in the country, each employing one anganwadi worker and helper to provide health, nutrition, and pre-school education for children up to the age of six as well as nutrition and health services for pregnant and lactating women and adolescent girls.

The anganwadi workers are considered volunteers and paid a monthly “honorarium”. In response to a question in the Rajya Sabha, the government said, “Anganwadi Workers and Anganwadi Helpers are “honorary workers” from the local community who voluntarily come forward to render their services in the area of child care and development to help the community for which they are paid honorarium. Such honorary workers cannot be treated on par with regular Government employees” (emphasis added).

Although the ICDS began as a pilot scheme in 1975, it has expanded to the entire country and some of its services are legal entitlements under the National Food Security Act, 2013 (NFSA). Yet, in most states, the payment that these workers receive is very low compared to the work they are expected to do. While the central government contributes Rs. 4,500 and Rs. 2,250 per month towards the honorarium of anganwadi workers and helpers, respectively, many states add to it from their budgets (ranging from Rs. 1,450 in Bihar to Rs. 19,700 in Tamil Nadu). 4Response from Minister of Women and Child Development to Unstarred Question No: 633, asked by MP Raghav Chaddha, answered on 7 Feb 2024

ASHAs are responsible for a host of health functions related to maternal and child health; non-communicable diseases; tuberculosis, malaria and other vector-borne diseases; and sanitation and clean drinking water.

Accredited social health activists (ASHAs) appointed under the National Health Mission, initially in rural areas and later in urban areas, are relatively new (since 2005) but they too face similar work conditions. ASHAs are paid an honorarium and not a salary, with a small fixed amount (Rs. 2,000 a month) to compensate for routine duties and a task-based payment for various activities. For example, “ensuring survival of baby and mother duo after 45 days of delivery” fetches an incentive of Rs. 500. 5Response from Minister of Health and Family Welfare to Unstarred Question No: 313, asked by MP Saket Gokhale, answered on 24 July 2024.

ASHAs are supposed to be the link between the community and the health system and are responsible for a host of health functions related to maternal and child health; non-communicable diseases; tuberculosis, malaria and other vector-borne diseases; and sanitation and clean drinking water. Mid-day meal cooks and helpers in schools often work for up to six hours but are paid a very low honorarium of Rs. 1,000 a month for 10 months a year. The tasks these workers perform are critical and involve some skill. Although they are supposed to be volunteers, they are expected to maintain extensive records and be as accountable as regular employees.

While anganwadis, ASHAs, and mid-day meal cooks are present across the country, the number of other honorarium-based workers (mostly women) in public employment in various state and central schemes has been expanding. Some examples include swachhta didis (women responsible for maintaining community cleanliness and spreading awareness about sanitation), pashu sakhis (women trained to provide livestock extension services), drone didis (women trained to fly drones for agricultural purposes), nyaya sakhis (women who facilitate resolving disputes through peaceful means), BC sakhi (banking correspondents), krishi sakhis (farmers and trained para extension professionals in agriculture), community resource persons, and so on. Most of these women are provided some training by the government, sometimes given a small honorarium, and are expected to carry out essential duties.

They are also sometimes expected to be paid by community-based organisations (CBOs) or self help groups (SHGs). While there is no consolidated count of how many such positions exist and all the tasks these women perform, it is now hard to miss them during field visits to rural parts of the country. Their work is mostly substituting (and subsidising) for services that the government should be providing in a regular fashion.

…[M]any anganwadi centres do not have a proper building, teaching-learning material is inadequate, weighing machines are dysfunctional, the food budgets are not inflation adjusted, and so on.

What is common among these women is that they are not considered employees and are poorly paid (sometimes even lower than the minimum wage). These low-paying “jobs” have few growth prospects. Based on the PLFS for 2019-20, the median monthly earnings of women in regular public employment was only Rs. 10,000 in the education sector, Rs. 7,500 in the health sector, and Rs. 10,000 in public administration. The corresponding figures for men were Rs. 31,000 in education, Rs. 20,000 in health, and Rs. 23,000 in public administration (Sinha, forthcoming).

These jobs are quite challenging because the resources and support required to fulfil tasks are usually lacking. For example, many anganwadi centres do not have a proper building, teaching-learning material is inadequate, weighing machines are dysfunctional, the food budgets are not inflation adjusted, and so on. More than 30% of the positions of supervisors and Child Development Project Officers (CDPOs), higher level staff who are supposed to monitor and provide supportive supervision, are vacant.

While there is no space to go over what this means for the quality of services provided, all these are examples of the kind of feminisation of public employment that is taking place in the country. On the other hand, in most parts of the country, these jobs are the only opportunities available to educated women (outside of agriculture).

Need to Improve Quality

In almost three decades between 1994 and 2022, the share of women among regular public employees has been increasing while the quality of jobs has been declining. This process of feminisation needs to be understood in the broader context of the neoliberal economic policies being followed since the 1990s. Across the world, the introduction of neoliberal reforms has been associated with fewer jobs being created in the public sector as a part of overall austerity measures. In this process of weakening the welfare state, women are more affected as they tend to be in lower-level or part-time/temporary positions that can be easily removed (Rubery 2013).

In India too, contractual jobs (not permanent positions) are now prevalent in regular cadres such as administrative staff at various levels, school teachers, nurses, and midwifes. Along with greater contractualisation, newer forms of engagement such as incentive-based workers, part-timers, consultants, and outsourcing have become more prevalent. The gendered division of labour and non-recognition of women’s unpaid care work in the household further contributes to the undervaluation of their work even when they are employed by the state. The reduction in public services or absence of it also increases the burden of unpaid (care) work on women.

On the other hand, despite these changes in the nature of public employment, it remains an important source of employment, especially for women in rural areas. There is not only an increase in the share of women in public employment, their strength in absolute numbers has also increased manifold, especially after 2005. The number of women in public employment in rural areas (based on NSS/PLFS and population projection data) almost doubled between 2005 and 2012, and quadrupled between 2005 and 2022. More accurate figures are not available as there is no consolidated data on all public employees under state and central governments, and various types of contracts.

The employment surveys could be underestimates but point to the underlying trend. This massive increase in public employment is mostly likely a reflection of the expansion of various welfare schemes after 2005. For example, the introduction of the MGNREGA, which is known to have high share of women’s participation, increased the number of women casual workers in public works. On the other hand, expansion of schemes such as the ICDS (number of anganwadi centres more than doubled after 2006), introduction of hot cooked meals in schools nationwide (in 2004), appointment of ASHAs (in 2005), and so on contributed to the number of women “regular” workers in public employment.

Such employment is often the only available option for educated women who withdraw from agriculture. This is especially true of women who are willing to work outside their homes but have to find employment within the constraints of having to manage domestic chores and care work responsibilities while dealing with the mobility restrictions placed on them both by cultural norms and the lack of safe transport facilities.

Interviews with frontline women workers conducted by the author in Bihar, Telangana, Delhi, and Chhattisgarh showed that while women complained about the poor conditions of work in the jobs that they were engaged in, they also said it was still better than the alternatives they had (even the low pay was higher than what they could otherwise get). Second, even though there were no written contracts, there was a sense that the employment would be available for a long period of time. These jobs also came with social acceptance and respectability and they felt they were “sarkari” workers. The jobs also allowed some flexibility in timings, were mostly predictable, and close to home. The support they received from their family members was also higher, though it was usually with the hope that they would become regular employees.

The advantages of expanding public employment are many, especially for women. The wide-ranging benefits include improving access to public services, achieving human development goals, enhancing gender parity in employment, and protecting workers against informalisation.

These jobs also offer opportunities for collectivisation. The unions of anganwadi workers and helpers are examples of some of the strongest trade unions in the country today. There are regular reports of women protesting for better pay and work conditions in many states. These unions also demand better resources for programmes as a whole so that they can deliver better services.

The advantages of expanding public employment are many, especially for women. The wide-ranging benefits include improving access to public services, achieving human development goals, enhancing gender parity in employment, and protecting workers against informalisation. But in India feminisation in public employment in terms of a higher share of women is coupled with increasing informalisation and a reduction in the quality of government jobs. While these forms of employment may seem beneficial in the short run because they are cost effective, the larger picture is one of missed opportunities and increasing inequalities.

Dipa Sinha is a Development Economist working on social policy issues in India.