On 1 August 2021, a nine-year-old Dalit girl died in “suspicious” circumstances in Nangal in Delhi. Her parents said that she had been raped and murdered by a priest attached to the local crematorium and some others. A few days later, her “remains” including “tissue” and “feet” were consigned to the flames by the family. Barely a few days after this crime had come to light, another Dalit girl was found dead in Trilokpuri, also in Delhi. And so it continues, with not a day passing without a grisly crime being committed against Dalits in the country, of which injury done to girls and children appears never-ending.

The pandemic appears to have worsened matters and a study of crimes against Dalits during the months of the virus notes that these acts are not to be viewed as ‘aberrations’ and the ‘perpetrators as individuals who are “bad people and not like us.”’ Rather, ‘it is important to understand that they are all products of a self-perpetuating, unequal, society that is structured to benefit those from the dominant castes’ (DHRDnet 2020, p10).

These are not facts we are unaware of. Dalit women and political activists have pointed out the nature of such violence (Irduayam et.al, 2006). Government reports, including of the National Crime Records Bureau have taken note of them. Studies that have addressed the working of the Prevention of Atrocities against Schedules Castes and Tribes Act, 1989 (PoA Act) have pointed to the manner in which the daily lives of Dalits are punctuated with acts of verbal and physical abuse (National Coalition, 2010).

The pandemic appears to have worsened matters and a study of crimes against Dalits during the months of the virus notes that these acts are not to be viewed as ‘aberrations’...

In what follows I situate this violence that has acquired a distinctive resonance during the pandemic in the context of the historical conjuncture in which we find ourselves. For the past eight years, we have been ruled by a government that has shown deliberate disregard for democratic protocols, institutions, practices and norms, relying instead on governance that is invested in surveillance, aggression and incarceration. In place of consensus, however craftily wrought, we have a discourse that is indifferent to truth claims, and repeatedly asserts official dogma in the face of relentless fact-checking and rationally argued dissent. These developments have unfolded within a changed political economy with the state favouring particular forms of capital accumulation, accompanied by a retreat of labour rights and of the rights of communities over land and water, and by a studied refusal to heed environmental concerns. This has resulted in governance that has less and less interest in the commonweal or even policy-led welfare and, which, instead, looks to the market to provide solutions for a range of issues, to do with production, employment, credit, and services of all kinds, including in health and education. These developments have proved consequential, especially with regard to the caste and gender questions.

Instrumentalism on social justice

Let me start with the caste question. With the careful tending and nurturing of Bahujan and Dalit electoral anxieties in Uttar Pradesh and the cynical cultivation of individual Dalit leaders in states like Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra in ways that answer to Dalit political histories and organizing in these states, an instrumental and complicitous political logic has been put to work. An equally utilitarian logic may be seen at work in the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) reluctant acceptance of reservation for the Other Backward Classes in educational institutions. Alongside such instrumentalism sits a brutal politics that is indifferent to Dalit social suffering as well as resistance. Not only is this evident in the restructuring of the economy, which has led to much misery for Dalits and Adivasis, but it is also what makes for brutality and violence against those who lay claims to their constitutional rights to life and livelihood. There are other proofs as well of this brutality. The devious and cruel ways in which the party fudged matters to do with Rohith Vemula’s institutional murder, the callous handling of the Hathras case (in which a young Dalit woman was sexually assaulted and subsequently died) by the BJP-dominated government in Uttar Pradesh, the treatment meted out to Chandrasekhar Azad by the same government, the continued incarceration of prominent Dalit (and Bahujan) activists in the Bhima-Koregaon case, the studied neglect of the various concerns raised by sanitation and care labourers, during the time of the pandemic and even earlier.

With the careful tending and nurturing of Bahujan and Dalit electoral anxieties in Uttar Pradesh and the cynical cultivation of individual Dalit leaders in states like Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra ... an instrumental and complicitous political logic has been put to work.

This manner of doing politics is not new (see Amrita Chachi 2020). The Congress was as committed to neo-liberal economic growth, and it had sought to hegemonize its policies in and through what has been termed inclusive neo-liberalism, but which, in the words of one of its critics, “tried to mitigate the detrimental consequences of commodification in order to deflect oppositional collective action” (A. Nielsen, quoted in Chachchi 2020). In the political sphere, it had even sought to work electoral—read caste—arithmetic to its own ends. While it had sustained a refurbished Gandhian approach that sought to accommodate Dalits within the polity, violence against Dalits and disregard for their constitutional rights have routinely been on display in Congress-ruled states. Likewise regional parties have not been far behind in reaping the benefits of a restructured economy and have been as adept at playing at caste arithmetic. Further, even in states that have seen sustained struggles for social and economic justice, Dalits continue to be harassed and hurt, if not murdered.

Yet the BJP’s instrumentalism regarding caste is distinctive. For one, this process has unfolded in a context that heeds the logic of algorithms, rather than the actual content and truth value of debates on these subjects. One has only to take note of the pronouncements of the BJP’s millennial adherents, routinely and deliberately directed against social justice, the anti-caste intellectual traditions and the rights claims of marginal people in resistance. From aggressive trolling that reeks of hatred against those who are opposed to the party’s policies to the studied impatience and righteousness that pass off for liberal thought in digital journals such as Swarajya, a space has been carved out for a politics of resolute ethical indifference and hatred. Secondly, the demand for adequate representation of marginal communities, in education and politics, which is a democratic and just claim, has been compromised by the BJP’s undemocratic politics. It is surely noteworthy that this has been done at a juncture, when being part of the state does not signal a commitment to social justice, rather it enables staking claims to a share in the spoils of governance through dispossession.

Rhetoric of women’s empowerment

The party’s approach to the gender question is equally significant. From criminalizing triple talaq to ensuring that there are more women in the forces, from having the prime minister speak up for girl children and their education to proclamations of zero tolerance for crimes against women, the BJP and its cohorts have attempted to ‘feminize’ matters to do with social equality, in and through a calibrated rhetoric of women’s empowerment. On the other hand, we have the state reneging on various welfare commitments, or fudging details of those that are in place, and passing off pronouncements in policy documents as proof of results achieved (Varma 2020). In addition, the callous public culture that the BJP’s leaders have helped create has made for casual and unregenerate misogyny: exhortations to compulsory Hindu motherhood, hatred-filled speech against Muslims, which warn Hindu women of the perils of the so-called “love jihad”, laws that expressly criminalise conjugal choice. All these and more are made manifest in public, under the cold and unblinking eye of the party’s patriarchs.

The manner in which the BJP has looked to resolve the caste and gender questions is somewhat telling...

The routine gesturing towards women’s empowerment and the disregard for substantive issues to do with gender justice might not appear too different from the visibility that was “allowed” to the women’s question during the years of the Emergency, when all rights were annulled. But the crucial difference is that such an “allowance” during the mid-1970s was not on account of state fiat or ruling party action, rather it was a reluctant concession to struggles on the ground. For, the years prior to the Emergency saw women’s groups across the country espouse feminisms that had emerged out of a complex history that assumed particular forms and expressions, depending on the geographies of organizing and articulation.

In contrast, the BJP’s rhetoric of women’s empowerment has been echoed by young, entitled millennials on the one hand, as well as women from an older generation, tied to the various organizations and families that make up the Sangh Parivar on the other. This group of women is actively invested in feminized power that leaves intact caste and class authority and in fact builds on both, as has been made clear by analyses that have examined the role of women in taking the agenda of the BJP ahead in Kerala (Devika 2020).

The manner in which the BJP has looked to resolve the caste and gender questions is somewhat telling. It has sought to co-opt a section of women and members of the other backward and Dalit communities into its violent project in rather fundamental ways, and, by that token, delegitimized all other equality struggles, including of labouring groups, peasants, subaltern caste groups set against the caste order, or those that have taken up against the Brahmanical core of the party’s ideology of Hindutva. The profound cynicism of this politics, which is brazen in what it has set about to do, has made for a common sense that is repeatedly peddled in the media and on the internet, which affirms the existing and unequal social relationships of production and reproduction.

Limited moral sense in caste society

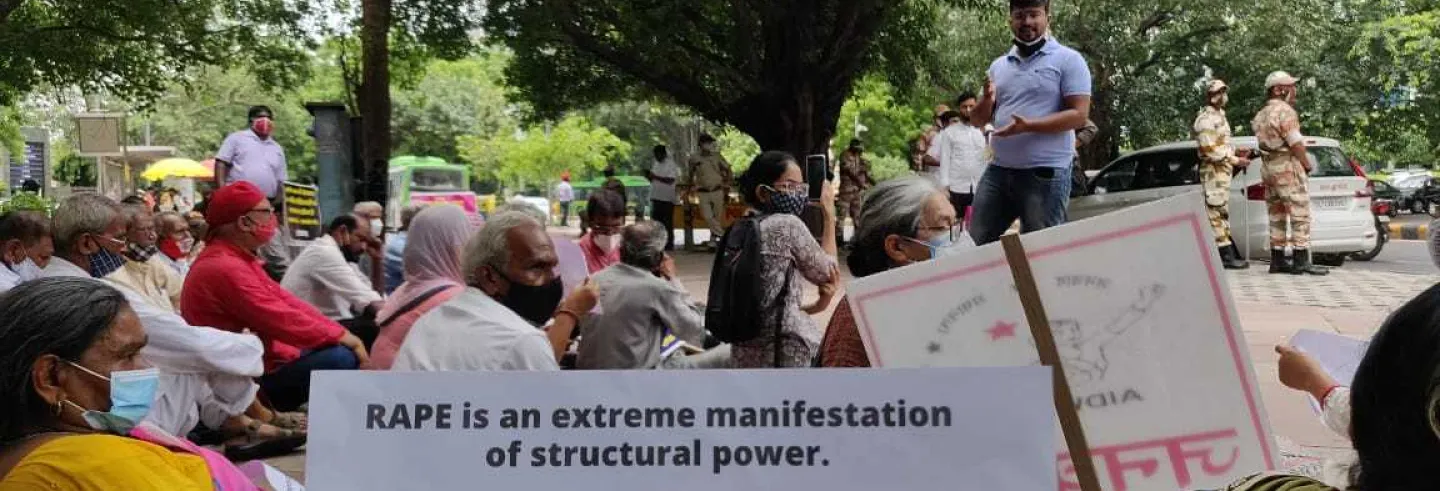

Opposition to this politics has been concerted and equally relentless, but, in the event, both feminist and anti-caste voices often get folded into a more generalized rhetoric against the BJP’s ideology and its manner of wielding state power. While this is absolutely necessary, equally important is to work at a slower and more persistent mode of critique that addresses the violence that is endemic to the social order, and which takes on board its changing forms as well as the fact that historically this has been necessary to sustain it. This is where the violence that Dalit women endure acquires importance.

At one level, this violence is thoroughly “normalized”, comprising acts that continually remind Dalits of their place and vulnerability in the social order. The terrible act that ended a child’s life in Nangal stands testimony to this. At another level, the violence that Dalit women endure or succumb to is rendered a spectacle, in order to mark it as “necessary” and a matter of triumphant relish. The spectacular nature of the violence has been evident in those instances where Dalits have resisted the social order, asserted their right to social and individual personhood, and sought to refute faith and custom. This is what we were witness to in Khairalanji.

At one level, this violence is thoroughly “normalized”, comprising acts that continually remind Dalits of their place and vulnerability in the social order.

Then there are instances where the violence might appear routine, but the contexts that anchor it are never quite the same. While it persists as a structural feature in situations where Dalit resistance is hard to sustain, in places and times where Dalit women resist, it emerges as counter-fury exhibited by the upper and dominant castes. The volume, Dalit Women Speak Out (Irudayam et al 2006) features several accounts that detail the conditions that called forth such fury and these have to do with economic demands, social access, cultural assertion.

In all instances, the violence against Dalits is as much an expression of the caste Hindu self as it is of the profound denial of the humanity of Dalits. The former has not received as much attention as it ought to. Those who routinely denigrate and hurt Dalit women express what Babasaheb Dr Ambedkar termed as the essential lawlessness of the Hindu social order. This latter, he observed, heeded a regime of law and right deemed so by scriptural fiat and social habit, and was immune to the demands posed by secular law or constitutional morality. Moral sense in Hindu society, he argued in a damning indictment, was exercised only if those Hindus who were admitted as their equals in every sense—often persons of their respective castes—were hurt or wounded. To that extent, this moral sense was limited and non-fraternal, and showed the Hindu incapable of “being good” in the fundamental sense of the term. Goodness, he made clear had to be actively sought out, nurtured, and acted out, but this required a transformation of the self, an act of “conversion” that would result in the making of a new ethical consciousness and being. (Ambedkar, 1936).

In all instances, the violence against Dalits is as much an expression of the caste Hindu self as it is of the profound denial of the humanity of Dalits.

Ambedkar’s critique made it clear that the incapacity for moral action premised on shared human claims and fraternity had as much to do with notions of personhood, as it did with considerations of power and authority. Viewed in this light, the caste Hindu perpetrator of sexual violence appears the very epitome of a system incapable of moral good and clarity, and, worse, his actions expressed a habitual and determined way of being in the world. This acute critique of Hindu selfhood has not been debated, as it ought to have been since Gandhi’s time. At best we have sought to come to terms with the disposition to commit such acts of violence by examining contextual and structural reasons, but in our public thoughts on the subject we have desisted from raising ethical and ontological concerns. To do so would have required us to turn somewhat against ourselves. That is, we have not sought to ask questions about the kind of persons we are expected to be, within the caste order. Our ‘personhood’ is not simply about what each of us is, individually, but shaped by our caste location. So, if we are to address caste critically, we have to, choicelessly, as it were, turn against our own caste selves.

Then there is the question of how we receive sexual violence. We are horrified by it, but it is also the case that this horror is leavened by a voyeur’s prurient interest, as is evident in how the “sexual” aspects of the crime grip our imagination. Descriptions of the crime in question, in popular and social media, continue to remain lurid. Even well-meaning campaigners for justice circulate photographs of the victim. For instance, this was done with glaring disregard for the child’s dignity and integrity in the Kathua case. Voluble whispers haunt discussions of what had transpired, whether the victim had said or done something to “encourage” those who assaulted her. In spite of the several decades-long battle that feminists have waged to detach considerations of morality and character from an appraisal of the crime, and the frenetic debates over the question of “consent” to sex that feminists have sought to complicate and criticize, much of civil society continues to sexually stigmatise the woman and even the child victim.

If we are to address caste critically, we have to, choicelessly, as it were, turn against our own caste selves...

As for the violence, it no doubt elicits anger and sadness, but it is also “normalized”. Linked as it is to sex, it is viewed as having to do with lust and desire, and with a lapsed moral sense. In other words, it is not marked as criminal so much as a twisted expression of otherwise legitimate male sexual entitlement. Here again, feminist arguments that have sought to regard it as an act of power, of authority exercised in impunity, are seldom heeded. For long, feminists have pointed out that sexual violence is a crime against bodily integrity and does not have anything to do with sexual expression or intent. But in a context where the female body continues to be fetishized in ever so many ways, its claims to personhood are easily overlooked.

Conclusions

Given that our very personhood heeds the logic of caste and gender in their autonomy as well as interrelatedness, it is small wonder that caste Hindu society fails to heed with the seriousness and sustained attention that it deserves, the phenomenon of Dalit women and children enduring sexual assault. Both Dalit suffering and Dalit resistance unsettle us because both point to what we do not wish to acknowledge: that there are no bodies that do not suffer when hurt, and there are no bodies that will not resist when they suffer, angrily or creatively.

Feminists understand the suffering and the resistance, but whether we acknowledge the ontological wounding delivered by the caste order, which requires us to continuously engage with anti-caste thought and political traditions that have called attention to it, is another matter.