‘Ankhon dekhi’, a Hindi phrase referring to an event that one has personally witnessed, was adopted as the title for a 2013 film where Bauji, the middle-aged protagonist, realises that there is a great gulf between what he was told about his daughter’s suitor and what he sees with his own eyes. Henceforth, Bauji refuses to believe anything he has not personally witnessed. He loses his job at a travel agency for he cannot reassure customers that a flight does, in fact, go to its intended destination. He refuses to believe that lions roar until he has heard one roaring.

This tragi-comic film is predicated on the practical limits of an individual quest for truth. Society delegates this task to reliable agents: journalists, investigators, and increasingly, recording devices. In the 21st century, however, we find that not only are our human narrators unreliable, we cannot even trust the evidence of devices. Images, video and audio clips are new tools for discombobulation. Take an old video, ascribe to it a new location, and voila! Falsehood emerges, harder and more resilient than truth.

India and the (mis)information superhighway

India is one of the world’s more misinformation prone nations. A 2017 study of Indian news consumers showed that nearly 83% of respondents were concerned about fake news, and 72% of them found it hard to distinguish between truth and disinformation. In 2019, Microsoft’s Digital Civility Index showed that the likelihood of Indians encountering misinformation was 7 points higher than the average in the surveyed 22 nations. That was in a year the Economic Times termed “the year of fake news.” But 2020, with the Covid-19 pandemic, pushed the disinformation stakes higher. There was a spurt in fake news that had already been debunked.

The relatively higher degrees of public trust in traditional news media [means that] they are more vulnerable to disinformation if it arrives by way of TV channels and newspapers.

According to a Lokniti-CSDS survey in 2017, over half of the respondents said they trusted newspapers and television news channels, compared with only 29% who said they trusted information received through WhatsApp or Facebook. This was despite the fact that cheaper data and higher Internet penetration have translated into at least 400 million users of WhatsApp in India, which has a population of nearly 1.4 billion. Another report, focused on urban India, found that print news leads in the Media Credibility Index, while the CVOTER Media Consumption survey of 2020 also suggests that newspapers are perceived as more credible than TV or digital media.

The relatively higher degree of public trust in traditional news media represents a double bind. On the one hand, people are more aware that the information they confront on social media is not necessarily credible. On the other hand, they are more vulnerable to disinformation if it arrives by way of TV channels and newspapers.

In order to keep the fabric of factuality intact, news organisations must not only deliver facts but also highlight falsehood.

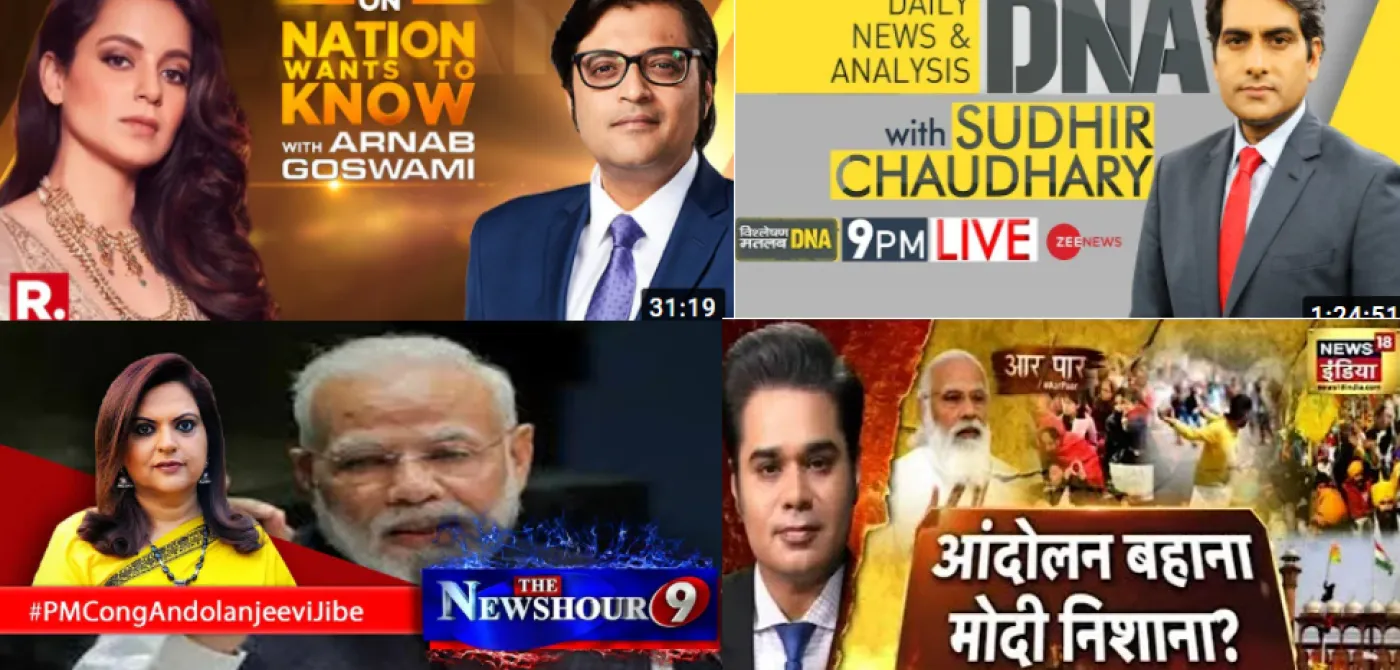

And it does arrive. A year-end list of ‘top fake news’ published by mainstream news media in 2017 featured Republic TV, ANI, Times Now, as well as print outlets like the Times of India, India Today, and the Hindu. (An apology was mentioned only in connection with the Hindu, which acknowledged that the mistake was a result of “failure to adhere to journalistic norms”.) In 2019, an election year in India, several mainstream media platforms published disinformation, including Republic TV, ANI, Times Now.

The lockdown period in 2020 corresponded with a spike in television viewing. The Financial Express reported that between 28 March and 3 April, just after the lockdown began, the average time spent viewing TV increased by 43 percent. News viewership grew by 251%. There was also a corresponding increase in fake news, including Islamophobic content.

Checks and imbalances

The challenge of manipulated facts and outright falsehood has been met by a corresponding increase in fact-checking initiatives. However, fact-checks are rooted in the assumption that journalists follow an ethical code, and that mainstream news media is largely credible. Separating fact from falsehood would become impossible if a critical number of hitherto credible platforms start publishing information without verifying it.

In her landmark essay Truth and Politics, Hannah Arendt wrote that while a lie punctures the “fabric of factuality,” it would stand out if the texture as a whole is kept intact. We can spot a lie in the form of a hole, or as “the junctures of patched-up places.” In order to keep the fabric of factuality intact though, news organisations must not only deliver facts but also highlight falsehood.

Many news organisations in India have failed to verify the information they publish. Nor do they fact-check their own output.

In practice, and in flagrant defiance of the Code of Ethics and Norms of Journalistic Conduct, many news organisations in India have failed to verify the information they publish. 1 In India, these codes are defined by self-regulatory bodies in the form of Norms of Journalistic Conduct issued by the Press Council of India (PCI), and the National Broadcasters Association’s (NBA) Code of Ethics. Nor do they fact-check their own output in appropriate ways.

One example is from 2019, when India TV aired a special episode on Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s early life. The show included an image where Modi appears to squat on the floor with a broom in his hand, suggestive of humble beginnings. Fact-check website Alt News pointed out that this image was debunked as fake a few years before, after it had gone viral during the run-up to the 2014 Parliamentary elections. Yet, the image was rebroadcast in 2019, another election year. After the Alt News report, India TV deleted the episode from its English website and YouTube channel, but not from its Hindi website.

In 2020, with social distancing norms and a ban on religious congregation coming into force during the Covid-19 pandemic, some journalists ran shows that suggested Muslims alone were defying rules. Several instances of fake news focused on the Tablighi Jamaat, a Muslim organisation that had held its annual conference in Delhi in March. Fact-checkers report that on 30 March, Islamophobic content online spiked. On his prime time show, Zee News’ editor-in-chief Sudhir Chaudhary described Tablighi Jamaat members as ‘suicide bombers’. The phrase ‘corona jihad’ was used and continues to exist as a tag on the Zee News website. The police tried to publicly debunk some false claims. Yet Zee News did not self-correct its false reports on the Tablighi Jamaat until the Firozabad district police specifically tagged the channel on Twitter, asking for misinforming tweets to be deleted.

Defiant misinformation by TV news outlets and newspapers [...] may even be upheld as ‘evidence’ of wrongdoing, leading to assault, arrests, or harassment of citizens.

Zee’s treatment of Muslims as dangerous actors was not limited to alleging their role in the pandemic. In a show aired on 11 March, Chaudhary displayed a ‘chart’ detailing what he claimed, without any evidence, as ‘land jihad’, ‘population jihad’, and even ‘film and music jihad’. Criticism from the journalistic fraternity did not faze him. The episode, chart and all, was uploaded to Zee News’ YouTube channel, which has over 13 million subscribers. The next day, Chaudhary complained on his show about intellectuals, liberals, “designer” journalists, and members of the “tukde tukde gang” (on which more later). The description of this episode on YouTube included the phrase ‘media jihadis’.

Such instances of defiant misinformation by TV news outlets and newspapers, which retain a higher degree of public trust, may even be upheld as ‘evidence’ of wrongdoing, leading to assault, arrests, or harassment of citizens. This damage cannot be undone through a corrigendum or an apology. The rising tide of misinformation can only be contained if the collective mediascape, and especially its most popular arms, adheres to ethical norms such as impartiality and upholding the dignity and safety of people impacted by their work.

Fact-check, counter-check and checks placed on facts

During the pandemic-related lockdown, an audio clip began circulating online with a male voice asking followers to visit mosques. It was claimed to be that of the Tablighi Jamaat chief Maulana Saad Kandhlawi, although there was no way of proving that the clip had been recorded recently. On 31 March, the Delhi Police registered a case against Maulana Saad.

The narrative took an unexpected turn when the Indian Express reported that the audio clip was examined and found to be doctored. The Indian Express’ report had cited an unnamed source but the reporter had reached out to the police for a response before the story went into print.

The Delhi police tweeted a denial, which was picked up by two popular right-wing news portals, OpIndia and Swarajya, whose stated aim is to counter what they term as mainstream media’s liberal bias. OpIndia published a story with the words “Indian Express Liar Liar,” alongside a graphic of a pair of pants on fire. It claimed to have “done an extensive fact-check writing” (sic) and concluded that the Indian Express story was “probably fake” (sic). The extent of fact-check, however, was limited to a denial from the Delhi Police.

Meanwhile, following the media-driven demonisation of the Tablighi Jamaat, the Enforcement Directorate filed a money laundering case against Maulana Saad and raided premises associated with the organisation in multiple cities. A Delhi lawyer even petitioned the High Court, seeking that the investigation against the religious leader be handled by the National Investigation Agency, which is a counter-terrorism agency.

Media coverage inserted the term ‘tukde tukde gang’ into public discourse in 2016 and it has since acquired a life of its own.

The media’s role in painting Maulana Saad as a dangerous criminal and in the circulation of audio-visual material of doubtful veracity was not an isolated episode.

In 2016, based on a Zee News report and video, Delhi Police filed a case of sedition against some students of Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) for chanting ‘anti-India’ slogans during a campus protest. Questions of the video’s authenticity arose after Zee’s footage and other videos circulating online were sent for forensic examination. Hyderabad-based Truth Labs found two of the seven video clips sent as evidence to be doctored using “media manipulation tools”. Yet, one of the doctored videos was shared on Twitter by an aide to the-then education minister — whose remit included JNU.

The media coverage of the videos inserted the term ‘tukde tukde gang’ into public discourse in 2016 and it has since acquired a life of its own. Sudhir Chaudhary of Zee News claims credit for its coinage but rival news anchors use it freely. The term regained currency when nation-wide protests were organised against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Union Minister for Law, Ravi Shankar Prasad declared that the ‘tukde tukde gang’ and ‘urban Naxals’ were responsible for the protests.

In December 2019, weeks ahead of the state assembly elections in Delhi, Home Minister Amit Shah talked about teaching the ‘tukde tukde gang’ a lesson. Yet, when a Right to Information petition sought details about this mysterious gang, the Ministry of Home Affairs admitted it had “no information concerning tukde-tukde gang.” The gang is therefore neither a fact nor is it allowed to recede from public discourse as a fiction.

Sociologist John Keane described post-truth as a vaudeville performance led by politicians, journalists, public relations agencies, think tanks and other players – a performance that intends to destabilise and disorient. The mainstreaming of the term ‘tukde tukde gang’ and its association with any expression of dissent or criticism of the government is one such act in the performance of post-truth.

Who reports on the reporters?

The author of Post-Truth, Lee McIntyre, defined post-truth as the political subordination of reality. One of the ways this has been done is through appropriating the language of fact-check. Factuality is further destabilised through a mode of disinformation that mimes its own manners and appearance. Every mechanism through which fact is sifted from falsehood becomes questionable. Checks are placed upon the power of fact-checks and the state arrogates to itself the right to check those who report facts.

TV channels are obliged to acknowledge and correct errors in a way that attracts “enough viewer attention”. However, observers would be hard-pressed to find any evidence of self-regulation in India.

If print journalists fail to follow norms, complaints can be taken to the Press Council of India (PCI), a statutory body chaired by a government appointee. Radio news is broadcast exclusively by state-controlled institutions. Electronic news media in India is meant to be self-regulated. Complaints can be taken to the National Broadcasters Association (NBA), which addresses them through the National Broadcasters’ Standards Authority (NBSA).

The NBA’s Code of Ethics and Broadcasting Standards states that “professional journalists should stand fully accountable for their actions.” Under ‘Principles of Self Regulation’, TV channels are obliged to acknowledge and correct errors in a way that attracts “enough viewer attention”. However, observers would be hard-pressed to find any evidence of self-regulation in India. In fact, when Zee News was asked to apologise and pay a fine for defaming poet-scientist Gauhar Raza as an ‘anti-national’, it did not obey immediately. The channel has featured more than once on ‘top fakes’ lists and, in 2019, it was found guilty of violating the NBA’s code of ethics. Despite these obvious red flags, Zee News’ editor-in-chief Sudhir Chaudhary sits on the board of the NBA.

The NBSA is also empowered to act on its own when a channel violates norms. It may even recommend to the government that the channel’s broadcasting license be revoked. But despite the proliferation of misinformation in 2019 and 2020, the NBSA does not appear to have taken notice. Complaints against channels were lodged mainly by citizens or by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting.

The Indian Penal Code does not have laws specific to misinformation. Therefore, people end up filing criminal complaints for defamation or, as in the case of Sudhir Chaudhury and Amish Devgan, charge them under Section 295(a) which pertains to the outraging of religious sentiment, or under Section 124(a) which pertains to sedition. In an attempt to deal with fake news during the Covid-19 pandemic, the Maharashtra state police also filed over a hundred cases under Section 107 of the criminal procedure code, which pertains to a breach of peace.

The involvement of law enforcement agencies poses further risks. Reporters may fail to do their job for fear of being arrested. The state could also book journalists who are doing an honest job. In either event, the involvement of the police only serves to fulfil the post-truth goal of the political subordination of reality. Questions have been raised about the government’s Press Information Bureau setting itself up as a fact-checker, since many of its ‘checks’ are merely official denials and not independent investigations by journalists. The crisis of public trust deepens.

In the event that an uncomfortable fact emerges, a counter ‘fact-check’ can make it go away. Fact-checking thus appears to be at risk of being turned into a performance.

Adrift in “a sea of information, pseudo-information, misinformation, and disinformation”, as sociologist Rogers Brubaker describes it, people may find themselves feeling powerless and unable to assess competing claims to factuality. Brubaker warns that there is a danger of people developing a mistrust of not just news media but of all institutions of knowledge, including universities.

Often, confirmation bias kicks in. People are tempted to believe whatever reinforces their prejudices or affirms their self-image. In the event that an uncomfortable fact emerges, a counter ‘fact-check’ can make it go away. Fact-checking thus appears to be at risk of being turned into a performance where players lob “fake news” sallies at their rivals while dodging fact-checks coming at them.

Truth as creative disruption

Keane has argued that post-truth cannot be challenged by those who are in the truth trade – journalists, lawyers, academics, activists, data scientists and others – unless they recognise that truth and post-truth are partners. Challengers to post-truth must therefore do what post-truth does: perform a bold, unpredictable facticity without fearing the destabilisation of their own establishment.

Roland Jurczok/ Jurczok 1001 attempted such a performance through his poem ‘New news’. In 2019, at the Tata Literature Live festival in Mumbai, Jurczok read out lines such as these:

fake news fake news you are fake news… great news I've got great news I love you

It was an obvious reference to Donald Trump, who has often dismissed journalistic interrogation as ‘fake news’, and it had an Indian audience fall about laughing. There is nothing funny about the weaponisation of disinformation, but the audience understood that the poem was the processes through which words like ‘fake news’ were stripped of meaning. In India too, officials have branded critical reportage as ‘fake news’. The poet had created a textual mirror and, unlike the politician-speaker, this mirror did not lie.

The Indian media fraternity has long subscribed to an unwritten code of silence […] breaking this code becomes necessary in order to highlight the punctures and “junctures” in the fabric of factuality.

In India, some resistance to post-truth has come from within the truth trade. The most visible response came from NDTV India’s Ravish Kumar. In 2016, he forced viewers to ‘see’ the crumbling of journalistic norms: on his show the screen faded to black as Kumar’s voice spoke of the metaphorical darkness into which news media was descending. A Ramon Magsaysay prize-winner, Kumar used the term 'Godi media’ to indict journalists who fail to interrogate people in positions of authority. Godi means lap and ‘godi media’ has since gained currency.

Individual critics have also come up with the term 'Modia' to highlight the media’s refusal to question the Modi-led government. One such critic is Ramit Verma who analyses topics chosen for debate on popular TV news channels on the YouTube channel, Official PeeingHuman. Rapper Rahul Negi alias Madara has written songs that spell out uncomfortable truths about mainstream TV news. In a track titled ‘Tukde Tukde Gang’ he identifies this gang with ‘sold-out’ journalists and politicians. Newslaundry is another website that critiques Indian news media and emphasises transparency of ownership. It also produces TV Newsance, “Your weekly dose of all the insanity that passes off as news on TV channels”, and documents the broadcast of hate speech through a series called Blood Lust TV.

These are highly performative critiques rather than traditional journalistic interventions in aid of factuality. The Indian media fraternity has long subscribed to an unwritten code of silence. Organisations might take sharply divergent editorial positions, but would not call each other liars in public. Breaking this code becomes necessary in order to highlight the punctures and “junctures” in the fabric of factuality. In this way, people may be reminded that there exist pockets of news that are not compromised, that a non-godi media also exists.

As Arendt had noted, “the result of a consistent and total substitution of lies for factual truth is not that the lies will now be accepted as truth, and the truth be defamed as lies, but that the sense by which we take our bearings in the real world – and the category of truth vs. falsehood is among the mental means to this end – is being destroyed.” If, as the Lokniti-CSDS survey suggests, that at least 50% of citizens trust TV channels and newspapers, the corollary is that about half no longer trust mainstream sources of news. The damage to public trust is serious.

Identifying wilful peddlers of disinformation may not be enough to reverse the gains of post-truth, or re-establish media credibility. The confrontational, high-visibility tactics by critics within the truth trade may be the last stand in defence of people’s grasp on reality.