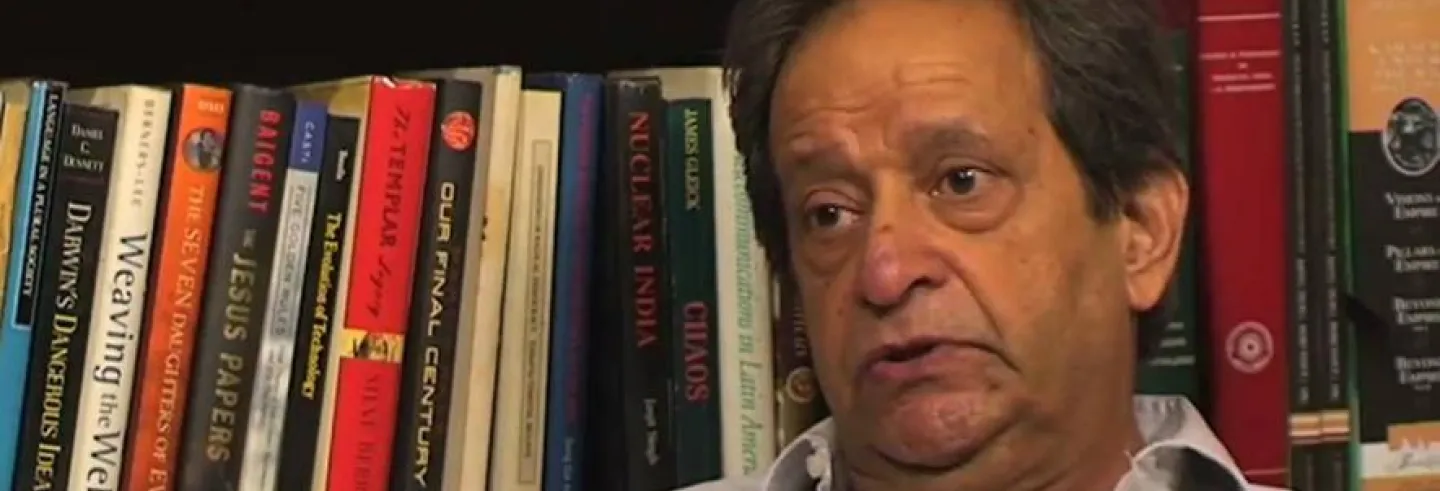

Aijaz Ahmad, a South Asian scholar with an abiding influence on many disciplines of the humanities and social sciences, died at his home in California on 9 March 2022. For the last few years he had been a professor of comparative literature at the University of California, Irvine. Over the decades, he had made important contributions to our understanding of imperialism and anti-colonialism, communalism and fascism, philosophy and social theory, as well as Marxism and communist politics.

A cosmopolitan personality

I first met Ahmad in the spring of 1992, when both "Reason and Revolution" were under unprecedented attack. But my early memories are of him talking about the poetry of Ghalib and Faiz, and of personal histories of loss, longings, migrations, and reaffirmations. He had come over to meet my grandmother, who had suffered a brain haemorrhage and was recuperating in Shimla. (My father taught at the university, and Ahmad was at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study.) The conversations that evening ranged over time, topics, and space: Persianate literary traditions, nuances of Hyderabadi and Lucknawi rivalries, the lives and loves of the comrades of the Progressive Writers Association, Canadian winters, and the Emergency. He effortlessly engaged my grandmother, university academics, and political activists in the same conversation. Aijaz sa’ab, as I got around to addressing him since, was a great raconteur and his frequent visits did much to revive my grandmother, both in health and spirits.

As the world reconfigured drastically during the 1990s, Aijaz sa’ab became a close family friend, someone my father would seek out to discuss philosophy and politics, and someone who stood by him in times of crisis, always ready with warmth and attention.

Ahmad was always aware of his class privileges which allowed him to escape Pakistan’s prisons for university in the United States, or for that matter to explore resettling in India...

For me, his accounts of growing up as a communist activist in Pakistan in the 1960s, facing hostile military dictatorships and violent Muslim fundamentalism, resonated at a time when Hindu communalism was a growing threat. His were not merely didactic accounts in the tradition of socialist realism. Ahmad was always aware of his class privileges, which allowed him to escape Pakistan’s prisons for university in the United States, or for that matter, his ability to explore resettling in India in his late 40s. Questions of class, of religious fascisms, of the Third World, of imperialism, the role of critique — or reason, as he often insisted — found easy habitation in his conversations.

As a scholar, he was the rare person equally at ease with philosophy and complex theory as with political polemics; someone who could traverse literary criticism, political economy, history, Urdu literature, and European literary classics. It was a learning experience to see him move across disciplinary boundaries as well as from high theory to lay conversations, from English to Hindustani. Chai with him at the canteen was often as educative as listening to him in his erudite professor avatar.

Intellectual firepower

The year 1992 was also when Ahmad published his standout book, In Theory: Nations, classes, Literatures. It came at a time when Marxism as method and as perspective was being undermined in the academy, while its politics was being demonised as totalitarian. From the ‘Left’ came post-structuralist critiques of Marxism: accusing it of being inadequate and determinist at best, and part of the white male gaze at worst. The liberal and conservative ‘Right’ attacked Marxism for its lack of freedom and of development, as intellectually sterile. As students in the university then, we were buffeted by these strong winds from the Northern academy. The sudden shift in academic orientation (pun intended), where Marxism was disparaged both as method and politics, made it increasingly difficult for progressives to engage and learn from it.

Whether one agreed with Ahmad or not, for an entire generation and more, his book [‘In Theory’] helped ground their engagement with the post-structuralist common sense...

Ahmad joined this battle in right earnest. In Theory’s defence of Marxism at its moment of greatest vulnerability remains an important contribution even after all these years. His nuanced yet eviscerating critique of Edward Said’s Orientalism is remembered today for showing the errors and shortcomings of the post-colonial canon. But In Theory’s abiding value has been as an exposition of how classical Marxist methods still allow us great creativity and insight into imperialism and colonialism. His engagement with Fredric Jameson warned Marxists against giving up too much of the foundational ideas of materialist dialectics (or critical realism as he often referred to it) in their attempts to come to terms with post-structuralism.

What made In Theory unique was that it combined polemic fire with intellectual creativity and an enviable breadth of interdisciplinarity. By showing up much of the post-structural, post-colonial criticism of Marxism as nothing but a strawman argument decked up in French high couture, Ahmad provided many of us a safe harbour: a space where one found intellectual resources to evaluate the attacks on Marxism and assess the claims of its rivals. It also helped us make sense of the attacks on modernity and secularism — attacks which often came from the same corner of the ring. Whether one agreed with Ahmad or not, for an entire generation and more, his book helped ground their engagement with the post-structuralist common sense gaining ground in the 1990s.

It was also from his pen that flowed some of the clearest class analyses of communalism as a specific South Asian phenomenon. He had come to India just as the battle with Hindu communalism had been joined. His was a unique voice, important because it brought to bear his experiences fighting Muslim communalism in Pakistan, and his familiarity with the politics of Islamic fundamentalism.

But he was always internationalist, methodologically. He could draw analogies and examples from the world over and yet ground it in the context of the political economy of India’s dysfunctional state. Ahmad insisted that was not just Germany or Italy that one ought to see to contextualise fascism, or Pakistan to understand communalism. Instead, he pointed out the experience of Iran’s clerical fascism as an analogy to learn from: the success of the Ayatollahs in capturing the Iranian revolution, and how they reaped the harvest of the Iranian Left’s mobilisation of the widespread discontent of the Iranian working class, peasantry, and middle class against the failures of the Shah.

Searching for a home

In the early 1990s, Ahmad had returned to India from the US and was keen to settle down here. As he explained, he wanted to get involved with the communist movements here as well as become part of India’s academic world. It was, for him, coming home to grow his roots back.

It was unfortunate that Indian academia could not find a stable place for him in any of its universities. He persisted despite many disappointments of short-term positions. Sometimes his being a foreign citizen would be made an excuse, sometimes his openly Marxist views and public positions, sometimes the fact that he was, after all, a 'Pakistani'. He neither gave up hope and became bitter, nor fell into opportunism for positions, as so many are wont to. He would happily accept invitations to speak at small meetings of trade unions and student groups, engaging in his easy, friendly style, full of the conversational panache that came naturally to him.

It was impossible to not recognise that for all the valour, the internationalism, the life-long conviction in Reason and Revolution; there was the unspeakable tragedy of him losing his home…

By the mid-1990s, Ahmad grew close to the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and remained so till the end. He was an exemplar communist intellectual, standing up for the ideals of Reason and Revolution, arguing that we cannot have one without the other. More importantly, he held that if we do not work actively for realising reason and winning the revolution, we are not living up to our potential.

Over these three decades, he had been an important voice telling us not to lose confidence in either Reason or Revolution. Yet he lived to see many of his ideals defeated (though I am sure Aijaz sa’ab would have quickly taken issue with me for saying this). As word of his passing came, it mingled with the news of yet another resounding electoral victory for Hindutva, in Uttar Pradesh, the state where he was born. It was impossible to not recognise that for all the valour, the internationalism, the life-long conviction in Reason and Revolution; there was the unspeakable tragedy of him losing his home, having to leave ‘Hindostan’ for America in the last years of his life, as the Narendra Modi government refused to extend his visa anymore.

But there were other, earlier, instances of loss too, of a more intellectual and political sort. When the Left in India became vulgar cheerleaders of that Iranian fascist Ahmedinejad, I wondered why Aijaz sa’ab’s clear voice of reason no longer explained India’s Hindutva through analogies of Iran’s Islamic “clerical fascism” that had so illuminated us just a decade before? How did the archetypal internationalist scholar-activist make peace with the Indian Left’s increasing recourse to nationalism? What did he make of the constant retreat of Reason and Revolution? Or of the creeping takeover of class politics by identity tokenisms drawn from the playbook of the very ideological errors he had so brilliantly exposed in In Theory?

Looking back, I suppose I never asked him these questions because, perhaps, all of us instinctively knew the answer and did not want to hurt those precious to us by proving futile points. And Aijaz sa’ab was “azeez” – precious — to us: to me, to my family, to the Left movement, to innumerable people, some of whom he may have never met. In his passing we have lost not just a stalwart intellectual, a warm friend across class, nations, age and positions, but also an ideal for whom study and struggle were never two distinct actions. Yet, for all this loss, he remains a presence with his writings, his example, his contributions to politics in Pakistan, America, and India. An internationalist, he was truly at home in the world of Reason and Revolution.

Aniket Alam is a historian of the Himalayas who teaches Computational Human Sciences at IIIT Hyderabad.