In a letter to the editor of the Times of India in 1951, an irate citizen from the south Indian town of Belgaum wrote about the national concerns around fertility control. According to F. Correia-Afonso, the act of planning for a family was attached to the economic well-being of the nation. In that context, he doubted whether the Family Planning Association of India (FPA), founded in 1949 to advocate birth control, could undertake such an exercise. Correia-Afonso argued that the sole purpose of the FPA was to offer contraceptives and to expect anything more would be foolish.

In 1951, four years after Independence, India was just about starting on a long road to population control and family planning. Letters like Correia-Afonso’s showed how the concept of family planning was yet to appear ‘natural’ to its intended audience. India’s educated classes were still trying to understand the process and its end goal. The link between family planning and economic planning was yet to become explicit.

Birth rates were soon going to become indices for whether India’s economic modernisation would succeed or not.

When Correia-Afonso established an umbilical cord between an individual family’s decision to use contraceptives to the nation’s wellbeing, he was reiterating Malthusianism. By then an established theory (though now discredited), Malthusianism forecast that populations increase exponentially (X2) while food output or agricultural growth occurs with arithmetic progression (+2). Malthusianism fuelled the nightmare that nations with birth rates higher than death rates would soon face shortages of food and other resources. The nation’s future was tied to individual choices on family sizes and perceptions of contraceptives. Birth rates were soon going to become indices for whether India’s economic modernisation would succeed or not.

Also evident in the letter was a suspicion about the FPA’s intent and purpose. Such a distrust had a history too. It was an organisation that had transnational donors from the United States, most prominently the Ford Foundation. Such linkages with foreign donors were not new. The Rockefeller Foundation had preceded the Ford Foundation in establishing primary health care centres, medical colleges, and in disease prevention in India (Kavadi 1999, Kavadi 2007). What was different about the public opinion about Ford Foundation was that its help came with conditionalities.

One such condition was the need of a national population control programme.

Population and the nation

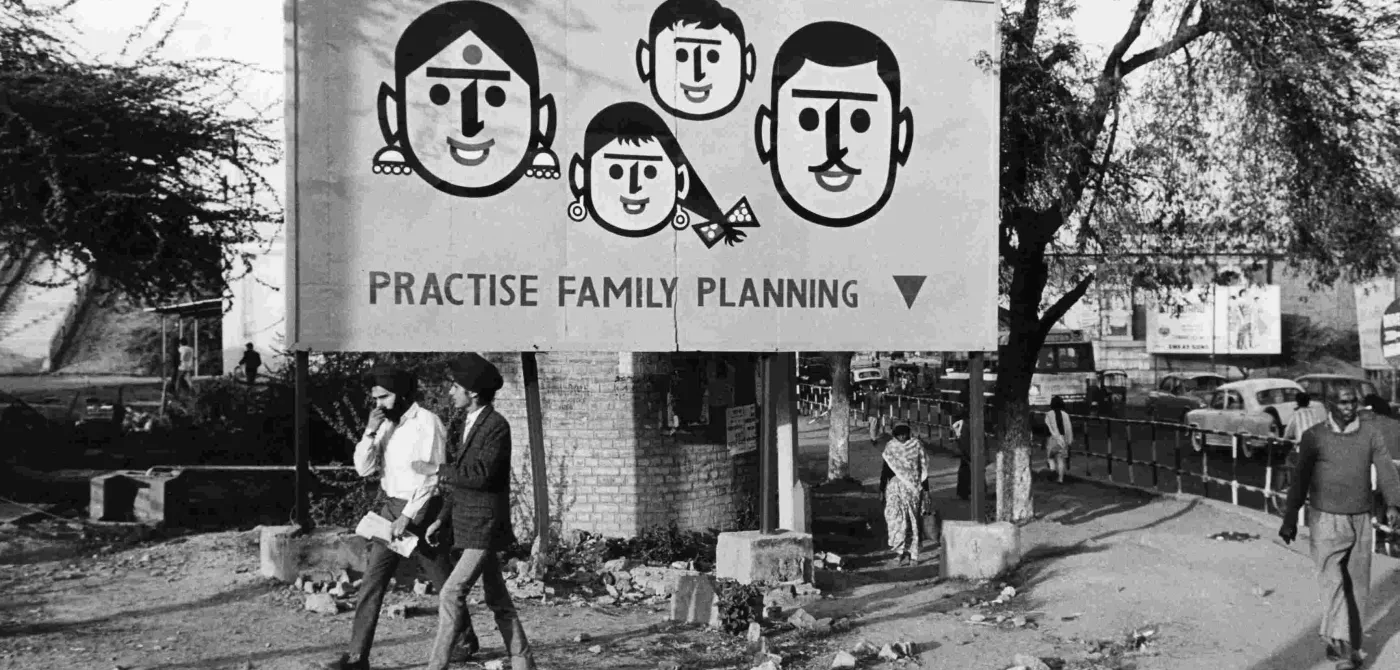

India’s Department of Family Planning flourished with funding from Cold War-era transnational philanthropists who softly peddled anti-communist projects in the developing world. With foreign aid, India’s national population control program quickly garnered legitimacy and attention in domestic circles. Voluntary organizations like the FPA and Planned Parenthood worked with civil bodies, political leaders, and social scientists to disperse Malthusian ideas within India’s middle classes.

India soon become deeply invested in legitimising a new way of life centred around a small family unit. The young couple in the city was the unit around which the state envisioned national economic progress. The money saved with raising fewer children could, among other things, boost India’s national savings.

Though transnational in nature, the popularity of the two-child family rested on local conversations about raising healthy children and rising above poverty. There was a growing consensus amongst the educated classes of the country that India needed to reduce its national birth rates. By planning the births of their children and opting for smaller families, couples were not only aspiring for material gains, but also a rise in their social capital. As advertisements of the period clearly understood, the emerging middle classes were also nascent consumers, who would strengthened the market for luxury goods, travel, and lifestyle products.

Thus, 1950s onwards, posters about ‘Family Planning’ would come to adorn markets, bus stops, hospitals, and cinema halls. Newspaper articles and advertisements incessantly asked people to use contraceptives. They implored young couples to visit Family Planning Centres regularly. The centres counselled newly married individuals about the importance of having fewer children and showed them ways to use contraceptives effectively.

How to contracept poverty

The circulation of new kinds of contraceptives — foam powder, intrauterine devices and condoms — was a collateral development of the global interest in modernising recently decolonised countries. For transnational aid organisations, contraceptives were a means to cure poverty in the newly decolonised world.

With nearly no access to non-surgical contraceptives and the increasing pressure to reduce birth rates, sterilisations soon became the default option of birth control for women who sought contraceptives.

Local bureaucrats and representatives of the funding organisations formed the expert community which decided the kinds of birth control devices were to be imported. Stereotypes about rural or uneducated women informed their choices. For instance, Ilana Löwy (2012) has shown how in the 1950s foaming powder, a spermicide which women could douse with before vaginal penetration, was not popularised in India. Policy makers assumed that rural Indian women were not capable enough to understand how to use them.

Organisations like the New York-headquartered Population Council rarely entertained feedback on the contraceptives they distributed in the developing world. While testing contraceptive devices, it was not enough if women in India complained about breakage or blood loss. Reports across testing sites (like Chile, South Vietnam, and Turkey) had to report similar side effects for researchers to reconsider the project. Additionally, the designs of intrauterine devices such as the Lippes Loop suffered because the pharmaceutical company that owned its license would not allow versions that were cheaper and more locally sourced in the countries which imported them. With nearly no access to non-surgical contraceptives and the increasing pressure to reduce birth rates, sterilisations soon became the default option of birth control for women who sought contraceptives.

When Indian state-run factories began producing condoms, the government’s advocacy shifted towards male contraceptive. Advertisements for Nirodh — India’s first domestically produced condom which the Ford Foundation helped design and manufacture — were aimed at male procreative abilities. Through the audio-visual campaigns instilling condom use, the state established who had the ultimate authority at home. Men were to use condoms to help the couple rise to the top of the income ladder. But the demographic profile from the time Nirodh entered the market shows a slightly more complicated picture. While the demand for condoms did increase, the popularity of surgical contraception for women did not drop.

Sterilising the poor

The 1960s marked how India transformed under the emerging elite consensus on family planning. Malthusian anxieties were evident in every aspect of governance. Overpopulation sidelined all other factors, including historical income inequality, as the main reason of underdevelopment. Newspapers headlines screamed of large infrastructural projects everywhere, as they also described the worrying increase in population. Such reports linked increasing birth rates to malnourishment, overcrowded housing, illiteracy, and ‘underdeveloped’ and ‘backward’ forms of family life. This link between material prosperity and family size, tenuous in the 1950s, had become common sense.

Peoples’ proximity to absolute poverty determined the state’s use of soft counselling to negotiate Malthusian fears. Studies by demographers had shown that working-class people across rural and urban areas understood the need of family planning and wanted to use contraceptives like condoms or IUDs (Agarwala 1970). Despite this evidence from the ground, planners and medical bureaucrats were adamant in targeting working-class clusters with sterilisations over other forms of contraception. When the demographer Sripati Chandrasekhar was elected to the Rajya Sabha in 1964, he suggested stringent measures and more permanent forms of contraception to the Parliament. (Not surprisingly, Chandrasekhar became the Union Minister of Health and Family Planning in 1967, under Indira Gandhi.)

When women visited health centres seeking advice, what they might not have known was that the social workers, dais (midwives), and doctors were being paid bonuses for sterilisations.

The emerging middle class used colonial registers of ritualised purity and majoritarian worries about economic growth to encourage sterilisations of historically impoverished and labouring populations. These deployments exposed eugenic concerns about the quality of population. Such fears had first emerged in the 1920s and 1930s, when Malthusian concerns overlapped with worries about ‘degenerate populations’ — malnourished, weak and therefore unproductive for the nation. Birth control advocacy involved key members of the educated elite networks of Indian society. Concerned doctors, sociologists and demographers had created Neo-Malthusian Leagues around the country which dispersed the urgent message of family planning (Hodges 2008). Indian upper-caste feminists too played a key role in foregrounding the link between women’s well-being, nationalism and recovering their agency through birth control (Ahluwalia 2008).

There was a disjunct between advertised methods of contraception and the ones that the health personnel offered in the counselling centres. When women visited health centres seeking advice, what they might not have known was that the social workers, dais (midwives), and doctors were being paid bonuses for sterilisations. This was a practice which started with the Mukherjee Committee of 1965, which recommended financial incentive and targets to ensure medical personnel performed better. These targets would be defined as per the region’s birth rate. Sterilisation soon became the most consistently accessible method of contraception for women.

With monetary incentives, the national health planning programme became even more skewed towards permanent forms of surgical contraception (Rao 1994). The collateral outcome of this financial incentive was that rural women became targets for sterilisations. In the face of a Malthusian nightmare, transnational funders encouraged this growth (Connelly 2008). This consensus to decrease birth rates had the (un)intended effect of encouraging creative forms of pushing people towards tubectomies and vasectomies. Though this streak was visible through the 1960s, it became more apparent only towards the end of that decade. Consequently, when the Emergency permitted authoritarian streaks of governance, coercive sterilisations became ubiquitous. Sterilisation numbers peaked in the Emergency years of 1975-77. (Connelly 2006) (Prakash 2019).

Even in the years before the Emergency, people were frustrated that the government was not doing enough to control birth rates. Calls for more stringent measures of population control were common.

What is striking is that even in the years before the Emergency, people were frustrated that the government was not doing enough to control birth rates. Calls for more stringent measures of population control were common in public forums. In a letter to the editor in 1971, an anonymous writer, ‘Citizen’, decried that the government’s spending on the family planning programme was not producing the targets set in the five-year plans. The mass of figures on the number of counselling centres and the money allegedly spent on them suggests that ‘Citizen’ could have been a bureaucrat or a private citizen watching the programme very carefully.

There is also some evidence that even before the excesses of the Emergency, people were beginning to be suspicious of sterilisations and population control. In January 1969, the Indian Express had a short and distant report on how more than 400 villagers attacked a primary health centre in Karnal district, Haryana. People also attacked the police who accompanied the camp and the doctors. The report did not mention why police were present. The report stated at the end that the Deputy Commissioner “denied that any death had occurred in the district as a result of sterilisation operations or that the people were being forcibly sterilised.” There was no commentary on what had led to the violence.

Healthy and productive populations

The ideal nuclear families in the city might not have created radical breaks from their rural relatives, but the relative autonomy accorded to the women allowed for couples to forge new identities while managing the expectations of the generation before them.

In 1971, a newspaper advertisement for Morisons Baby Powder carried an ‘interview’ with a Mrs Mathur, a ‘modern housewife’ (who is clearly upper caste and upper class). Along with her displaying the marks of an ideal modern mother — educated, professional, prioritising the home, allowing children freedom but not too much money, researching for baby products — Mrs Mathur also voiced a political message: support for abortion.

Eugenic concerns for productive and healthy populations produced intersections as this between the middle class desire for healthy children and anxieties about unsafe abortions. The Medical Terminal of Pregnancy Act that legalised abortion — passed a few months after the Morisons’ advertisement — went beyond the immediate agenda of advocating family planning to further disperse Malthusianism and displayed deep worries about the reproductive capacities of non-Savarna women and their health.

The Act held together two contradicting impulses. Interrogating the parliamentary discussions shows how the act legitimised women’s’ decisions to abort, while also recognising abortion as a mode of population control (Madhavan 2014). As legislators discussed the bill, they agreed that the need of the hour was to provide a way for poor women to access medical care for abortions and to avoid quacks. Safe abortions came up as an agenda needing urgent legislation. But the bill, coming at a time when newspaper reports and editorials expressed anxieties about rising births, indicate a larger vision of supporting the two-child family in every which way possible.

Similar contradictory arguments formed part of the legislation which amended the Child Marriage Restraint Act in 1978. Though the Morarji Desai-led central government passed the amendment to rescue young women and children from forced marriages, it also paid heed to the demographic logic that reducing the span of married life of young women would help in population control (Forbes 1979).

The legacy of population control

As of 2020, India has reached replacement levels of fertility: the national birth rates and death rates have closed in on each other (Shreya Khaitan, Indiaspend 2020). As the country’s fertility rates drop, the rhetoric of population control should logically die down. However, the scenario is the opposite.

No longer do we see the emphasis on family size as a tool of national development. Population control has become a rhetoric to restructure the Savarna Hindu family towards more eugenic ends and to stoke fears of Hindus being overtaken by other religious communities in garnering national resources. Even as the myth of large Muslim families remains as false as ever, political leaders affiliated to the RSS raise the slogan of Hindu Khatre Mein Hain (Hindus are in danger of being wiped out).

Other voices call for stripping a family’s basic rights away if they have more than two children. There have been efforts to ensure government servants and panchayat leaders have nuclear families. It has become easier to blame individuals for their reproductive choices than to examine how family sizes reflect one’s trust in the state to provide food and homes.

Such rhetoric is a convenient tool to erase the way the nuclear family in India emerged as a way for the majoritarian middle class to establish their dominance in the country’s economic development. The same middle class abetted the state as it used population control for eugenic needs.

Variations between states in the fertility transition towards nearly equal birth and death rates are lost in the political rhetoric about the need for population control.

The southern states of India heralded the trend towards slowing population growth with a strong preference for two-child families across rural and urban geographies (Guilmoto and Rajan 2001). Fertility control in these states was associated with women making sense of their role in the Malthusian economy. Northern Indian states, especially Uttar Pradesh, have shown consistently high fertility rates. They have also shown tendencies of coercion and illegal means of population control.

Such variations between states in the fertility transition towards nearly equal birth and death rates are lost in the political rhetoric about the need for population control. There is no scope for doubts about how a substantive welfare state could easily address poverty. Within this alternative schema, the state would need to worry less about birth rates and more about disease prevention, health and nutrition levels of the country.

Even as the demographic scenario has changed, contraceptive use continues to be a women’s burden. Notwithstanding advertisements of men exhibiting their masculinity by using a condom, female sterilisation continues to be the most used form of family planning, as it has been since the 1960s.

Tubectomies are the dominant form of birth control that health centres offer women of specific populations: Dalit, Adivasi and Muslim women.

Regardless of global criticism of targeted sterilisation, India continues to see tubectomies as a way to reduce birth rates. Tubectomies are the dominant form of birth control that health centres offer women of specific populations: Dalit, Adivasi and Muslim women. One cannot help but think about the women who died in 2014 after attending a sterilisation camp in Chhattisgarh, due to infected instruments used in the process. The women may have volunteered to be at the camp, but the legacies of family planning had certainly made it hard for them to access other options for birth contraception. As late as 2020, mass hysterectomies were being performed in rural Maharashtra. Originally intended for removing cancerous cysts and fibroids in the uterus, the women in this case chose hysterectomy to ensure no loss of wages due to menstruation.

Such issues cannot be addressed only through the rhetoric about needing population control. The middle class needs to introspect how the rhetoric is based on incorrect or old data. What can be said without any hesitation is that every time someone raises an alarm about overpopulation, it is to unleash another round of incentives for its bureaucrats to push people towards sterilisations.