Some years ago, I was part of the legal team for an accused in arguments before the Delhi High Court. Hearings went on for months and we used to carry trolley-bags full of binders that our senior lawyer painstakingly read from for the court. As did the other side. Ultimately, the petition was dismissed. What was it all for, you ask? Not final arguments in an appeal, but to get bail for an undertrial accused of having driven his wife to death.

I am often part of bail hearings where persons are accused of bodily harm, fraud, corruption, money laundering, and so on. Scarcely are the frequent dismissals (or the rare wins) accompanied by media discussions of courts having extinguished the constitutional promise of personal liberty by keeping an undertrial incarcerated (or of having reaffirmed our faith in the system). If anything, the coverage of some of these cases reflect elation at the fact that bail has been denied to 'such' persons.

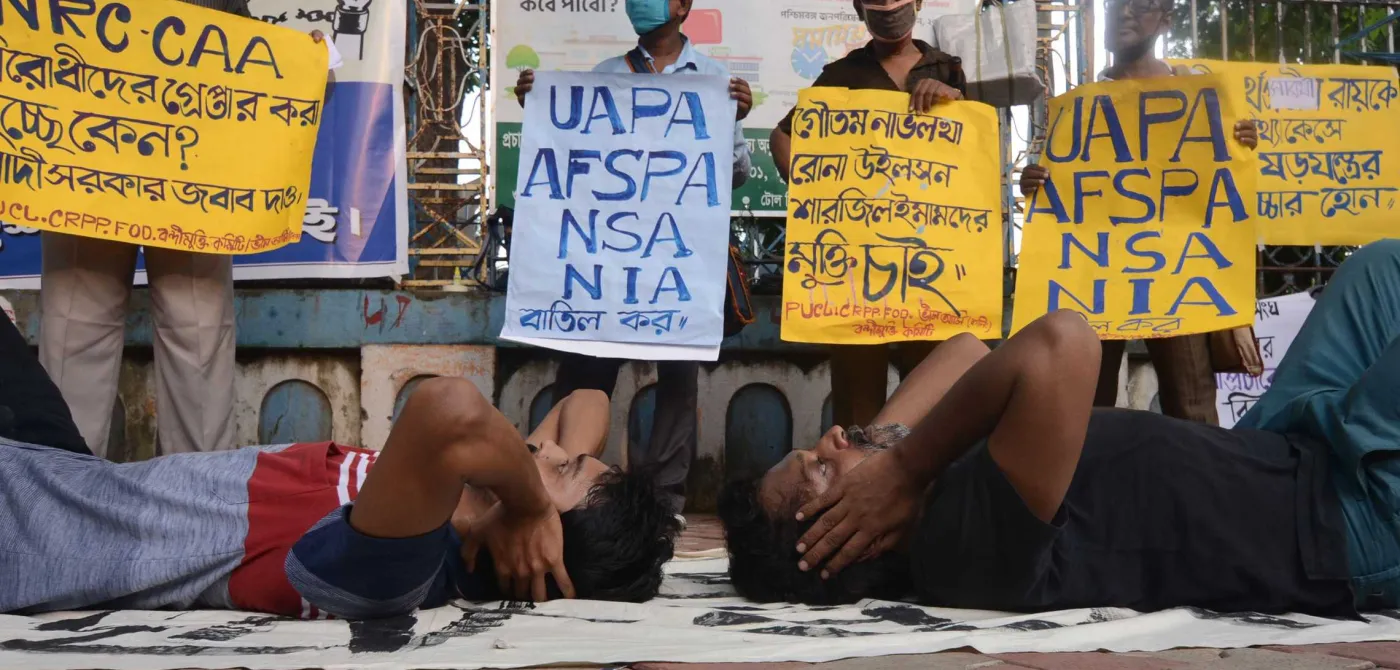

In the same professional universe, there have been a few cases involving persons accused of terrorist acts or sedition for their allegedly inflammatory speeches. Here, bail orders have attracted a lot of attention. If bail is granted it is a triumph. When bail is denied, it is an opportunity to discuss why the system needs to reflect on its shortcomings and is accompanied by calls for repealing the law or to try reform it.

How should society treat those who have been arrested as accused of a crime, but have not yet been convicted?

From my vantage point, when it comes to the criminal process, the fraudster and the revolutionary are two sides of the same coin. Both are at the mercy of allegations levelled by the state and are routinely jailed as undertrials on the strength of such allegations. I refer to this as the 'front-loading' of criminal justice in India.

Setting up the problem

Society recognises that some kinds of conduct are too egregious and ought to be treated severely with stiff sanctions and labels such conduct as 'crimes'. It establishes a detailed set of rules on how to establish guilt through a trial before judges trained in these rules, to set up institutions to apprehend those committing crimes, to gather proof against the accused, and to prosecute them before judges. Recognising the severity of these sanctions and the stigma that such censure by authority carries, society also commends the value that persons ought to be presumed innocent until proven guilty. (For a more detailed discussion on the concepts of criminal law and responsibility, Nicola Lacey’s work is a great place to start.)

It is argued that some delay is built into the system to prevent hasty decisions, driven by the emotive context...

In all of this, a question arises: How should society treat those who have been arrested as accused of a crime, but have not yet been convicted? As they are presumed innocent, should they be allowed to remain at large till a judge can decide upon the question of guilt or innocence? What if these persons flee and do not submit themselves to a court’s judgment? What if they destroy evidence? What if they commit further crimes? These obvious issues lend themselves to a solution: bail, a legal fiction where persons are not completely free but conditionally so till the adjudication of their guilt or innocence. It respects the presumption of innocence, while also safeguarding the process that has been created to test this presumption.

Conspicuously absent in this ideal depiction of the process is the fear and loathing that crime generates among people, as well as the time and effort it takes to travel from accusation to guilt in the process. The emotive context surrounding crime prompts quick social judgment and condemnation by us. This fear shortens the distance for the ordinary person from someone being accused of a crime to being labelled as actually having committed it, a distance that the law urges us to maintain during the trial process.

A victim might be more satisfied than the accused with the delay so long as the accused remains in custody pending trial...

The time and effort consumed by the criminal process is equally significant. Some delay is built into the system to prevent hasty decisions and enable reflective judgements. The value of time is such that it can transform the meaning of the justice that the criminal process intends to deliver. But it is impossible to scientifically determine how much delay is reasonable and the impact that delays have on both victims and accused persons. A victim might be more satisfied than the accused with the delay, so long as the accused remains in custody pending trial; an accused out on bail might be more pleased than a victim if a trial labours on. In either situation, it is important to consider the impact of such delays on the direct participants — the accused, victims, prosecutors, police, judges, and society at large — and on how they think about the presumption of innocence and final verdict.

The presumption of innocence was designed to strike a balance in what was always imagined as a temporary phase of accusations pending adjudication. The longer the phase bears out, the more tenuous the presumption becomes. It is at risk of either being overrun by the desire to condemn or calcifying into a state of permanence.

The Indian criminal process

These are, arguably, also the theoretical underpinnings of the Indian criminal process. Based on an architectural design harking back to the mid-19th century colonial codes — the Indian Penal Code 1860, the Criminal Procedure Code 1861, and the Indian Evidence Act 1872 — our criminal process gives pride of place to a trial designed to test guilt or innocence. It facilitates that idea of distancing accusation from judgment by creating various critical stages of judicial scrutiny that every case must pass. There is thus judicial scrutiny of the allegations that emerge after a police investigation, at the stage to decide whether charges ought to be framed, and, of course, at trial.

The point is not to have the same level of analysis at each stage, but a funnel approach. The court takes a prima facie view of the allegations at the start; then, at the stage of charge, sifts through the material gathered by the prosecution; and during the trial, receives oral and documentary evidence, giving both sides a chance to cross-examine the others’ witnesses. The repeated scrutiny is not only horizontal — many stages before the same court — but also vertical, where an aggrieved party can challenge all kinds of interim orders including the final judgment before at least two courts. This makes the process potentially a very time-consuming affair, although it enhances the probability of securing a dispassionate reflection of facts.

At the same time, the criminal process recognises the value of protecting society from possible harm and the threat of persons absconding. It confers on the police broad powers of arrest without prior warrants and in some cases empowers them to use deadly force against suspects. It recognises a broad class of “non-bailable” offences where bail is not given for the asking but is a matter of judicial discretion. The principles upon which the classification is based are debatable and not statutorily prescribed, but the gravity of the offence is often indicated as the primary factor.

The legislative history in the post-Independence period suggests that delays, more than anything, have determined changes to the bail system generally.

Empowering police with broad arrest powers and creating a distinct class of offences where bail is not a matter of right ultimately privileges the need for society to 'feel safe' in the immediate aftermath of an alleged crime. Thus, despite creating a lengthy system to test allegations, the law also allows for allegations to justify arrest and custody. This is reinforced in how the law regulates the exercise of judicial discretion in matters of bail.

The principles for this exercise of discretion have never been statutorily prescribed beyond the statute negatively prescribing that magistrates ought not to grant bail in cases involving alleged offences that are punishable with life imprisonment or death. Since the 19th century, the nature of accusations have also been recognised as being a relevant consideration by courts for deciding bail applications, besides determining the likelihood of an accused fleeing during pendency of the case or otherwise thwarting an impartial prosecution by tampering with evidence.

How has this process fared in practice? The legislative history in the post-Independence period suggests that delays, more than anything, have determined changes to the bail system generally.

In 1954, Parliament discussed a comprehensive bill to amend the Criminal Procedure Code of 1898. One of the legislators’ principal concerns was the need to speed up the trial process, noting that an accused remained incarcerated through a trial in most cases. Delays thus rendered eventual acquittals meaningless. However, rather than making it harder to arrest or making it easier to get bail by narrowing the class of “non-bailable” offences, the solution arrived at was the recognition of a new right to "default bail" if the trial did not conclude within a certain period.

Rising delays were again a key justification for pushing ahead with a new code, enacted in 1973. This code did not mark a departure from the theoretical underpinnings of 1861. Trials remained the main event of the process, arrest powers remained broad, and the right to bail remained confined to relatively minor crime. The 1973 Code continued with the idea of default bail (Section 437(6)) and extended this to fix a period for completion of the investigation in default of which a right to bail would accrue (Section 167(2)). It also recognised a new relief of anticipatory bail (Section 438), which I will come to later.

It is important to note that the past 50 years have also witnessed the growth of statutes that further narrow the scope to get bail. How this occurs is important and, again, confirms the primacy given to allegations. At this preliminary stage of bail, an accused is required to convince the court that she is “not guilty” of the alleged offence. Most of these pertain to the idea of grave crimes such as terrorism, but there is no rule restricting their scope in such fashion, allowing governments to introduce them as and when they please.

[T]he past 50 years have also witnessed the growth of statutes that further narrow the scope to get bail.

Thanks to the National Crime Records Bureau, it is possible for us to examine whether the new Criminal Procedure Code achieved its objective of reducing delays in the system. As I have discussed elsewhere, a year-on-year comparison suggests that figures of pending cases in trial courts have only been rising ever since. Completed criminal cases (for general offences under the Indian Penal Code) increased to around 12 lakhs in 2019 from around 3 lakhs in 1971; but during this time, pending cases went up to 1.12 crores from around 6.5 lakhs.

Pending cases in courts became more pronounced from the 1990s, as the pace at which police completed investigations quickened and cases reached the courts more rapidly. This has led us to the staggering figure of a reported 2.8 crore pending criminal cases in trial courts across India at the end of 2019. On an average, it takes at least one to three years for cases to finish. Amost half of these trials end in acquittals.

For the past 25 years, data on prison population has also been published together with the reports providing pendency data. I have taken up a broad overview of this data and the issue of undertrial incarceration elsewhere. Two points have to be flagged. First, undertrial prisoners have consistently constituted more than two-thirds of the total prison population, with the last decade showing a steady rise to bring us to 69% of prisoners being undertrials at the end of 2019. Second, the time spent in custody as an undertrial (even though the data is not sufficiently granular, not linked to the kinds of crimes for which persons are detained) confirms that from 1995 until 2019 a majority of undertrials continued to spend up to three months in custody. But worryingly, the share of this group has declined as average lengths of incarceration have steadily increased.

Cases in which 'society’s cry for justice' is supposedly loudest, are those where a judicial determination of guilt or innocence takes so long that the cries can barely be heard.

The upshot is that most accused persons are arrested and detained in jail for more than a day during the pendency of a case. A vast majority of these undertrials are ultimately released on bail, but the months they spend in custody keep increasing with each passing year. At the same time, almost 90% of the cases instituted in a year remain pending at the end of that year, so the gap between initial accusations and judgment is at least a year, and probably longer for more serious crimes. Thus, cases that are likely to take the longest to conclude are those where persons are likely to remain incarcerated as undertrials for the longest period. The cases in which 'society’s cry for justice' is supposedly loudest, are those where a judicial determination of guilt or innocence takes so long that the cries can barely be heard.

Between accusation and condemnation

The criminal process has remained a steadfast component of legal systems for centuries as, till now, it seems to be the best way to regulate the imposition of imprisonment and censure. The harshness of these consequences carries legitimacy owing to the process through which they are imposed. But, as we have seen, this process is built upon contradictions of sorts. It must be quick to respond while being deliberate to avoid making errors in haste. The reality that it is impossible to achieve a perfect balance has meant that every jurisdiction arrives at its own understanding of how different values and interests should be treated.

For India, pursuit of the ideal has been marred by constantly rising pendency, bringing us to a point where the most common adjective for the criminal process appears to be 'broken'. It would be more accurate would be to call it overwhelmed by the burden of 2.8 crore pending cases. This 'broken' system continues to justify its value to society by a front-loading of criminal justice: through a performative determination of the merits of a case during bail hearings.

The emergence of front-loading is arguably a result of both legislative action and omission in equal measure.

The emergence of front-loading is arguably a result of both legislative action and omission in equal measure. Governments have continued to retain broad arrest powers for a wide variety of offences, despite the consistent evidence of wide misuse of such powers taking place across agencies. Time and again, governments have chosen not to broaden the right to bail, either by widening the category of bailable offences or by creating a presumption that bail ought to be granted regardless of the allegations, unless it can be demonstrated that a person might evade proceedings or pose a threat to others.

Instead, there has been express recognition that bail discretion should be affected by the gravity of allegations, creating a presumption that magistrates should not grant bail if accusations involve offences punishable with life or death unless an accused can convince them that she is not guilty. The only notable procedural innovation of 1973 to check misuse of arrest power, anticipatory bail, also indirectly played up the front-loading of criminal justice. It allowed bail prior to arrest if a judge decided that the accusations were meritless or mala fide.

The importance of the seriousness of accusations as a criterion to decide bail applications has been recognised judicially. This, naturally, required engaging with the merits of a case. While courts have insisted that they should not proceed on a meticulous determination of the facts at the stage of bail, that has not stopped bail hearings from transforming into exercises where the sole focus is determining whether a person accused of certain crimes deserves to be released on bail or not. The seriousness of accusations, one relevant factor among many to decide bail, becomes the first among equals.

Some of the most pronounced expressions of this front-loading appear in the context of white-collar crime. The Supreme Court has created a body of law that says that because economic offences threaten the 'fabric of society', persons accused of such offences ought not to be released on bail, a sentence that encapsulates how the gap between accusation and condemnation has vanished. In the context of white-collar crime, the performative condemnation is often coupled with attempts at courts providing restitution to aggrieved persons at the bail stage itself. Bail becomes a discussion about what the accused is willing to pay for restitution, with figures arrived at purely based on the initial accusations.

This practice is so routine that the Supreme Court has criticised it more than once. However, the Supreme Court has also willingly lent itself to this performative restitution. An old instance of this was the Uttar Pradesh NRHM Scam — still pending trial — where the accused were released on bail / anticipatory bail by the Supreme Court on depositing an amount proportionate to the loss allegedly suffered by the exchequer. A more recent example of bail-stage restitution is the case of Sanjay Chandra, the former boss of real estate firm Unitech, who was granted bail in October 2017 by the Supreme Court on a condition of depositing Rs 750 crore, and then was not released as the deposit was not done within the stipulated timeline.

The Supreme Court has created a body of law that says that because economic offences threaten the “fabric” of society, persons accused of such offences ought not to be released on bail.

A criminal process that enables easy arrests and in which courts actively consider the gravity of accusations at the stage of bail to engage in pseudo-condemnation, going so far as to even engage in restitution, bridges the gap between accusation and condemnation that is created by delays. It sends a clear message that it is also aware of the value of time taken by the process and reassures society that its interests will not be entirely ravaged by delays.

The costs of front-loading

Front-loading of criminal justice carries obvious value for the aggrieved persons who form the amorphous body of a society wronged by crime that is aware of the delays that cripple justice delivery. The sanction and censure, and sometimes restitution, that the trial might provide after years are available at the very start of the process. However, it is important to consider the cost at which this benefit is provided. For me, two stand out: the empowering of the executive and a diminished value of the presumption of innocence.

If the process lends itself to trading in judgments on accusations, it is only natural that the agency that crafts those accusations and controls the narrative will determine the course that follows. This is more so at the stage of bail where an accused person is not entitled to bring in evidence.

In some measure, personal liberty stands surrendered to the whims of law enforcement agencies, who are incentivised to trump up accusations that are already heady owing to the heat of the moment. The power wielded by governments becomes even more pronounced if we consider that it can define crime however it wants to and fetter judicial discretion available to courts at the stage of bail, as has been most visibly done in context of the draconian Unlawful Activities Prevention Act.

Even if custody might be justified initially for some time on account of serious accusations against an accused, perpetual incarceration is not.

Eroding the gap between accusation and condemnation makes it difficult to comprehend the need for a presumption of innocence. The reaction to cases at the initial stage, branding persons as criminals and celebrating denial of bail or even police killings, reflects this disintegration. The law itself does not do away with the presumption outright. Rather, in the wake of a suspected crime, it has reoriented its axis to bring it in line with the privileging of accusations.

This has been buttressed by engrafting different kinds of default bail — bail if investigation is not finished timely, or if a trial begins but is not finished timely, and now through Section 436-A bail also if the case is lost somewhere in the middle for too long. Even if custody might be justified initially for some time on account of serious accusations against an accused, perpetual incarceration is not.

The presumption of innocence appears to then live a curious half-life. Legally it is strengthened as delays mount, while realistically it diminishes in value for the person who loses her life in jail without being pronounced guilty of a crime.

Struggling to make sense

The structural constraints placed upon the criminal process are all too real. The police and courts are both underfunded and understaffed, leading to long delays in investigations and trials. These are delays that have the potential to render the criminal process entirely meaningless by either requiring that it completely surrenders itself to the weight of initial accusations or by releasing all accused persons to bail as a matter of rule.

In such a scenario, time becomes of immense importance. Everyone is aware that judgments are far off in the horizon, closure made nearly impossible due to a tiered structure of appeals. This colours the justice ultimately delivered to all participants. Out of the necessity to try and satiate society’s lust for punishing and othering a criminal, bail hearings emerge as an alternate site of justice with courts engaging in pseudo-condemnation to justify imposition of lengthy jail terms before a conviction.

It is convenient to justify the existing scenario, as I find myself doing at times, as the optimal way in which a sub-optimal system delivers justice. Such thinking might help to digest the peculiar kind of justice that our process delivers. But, it is only making a virtue out of a cruel necessity and mildly better than closing our eyes in the hope that it will stop the fire burning through the house. A burning house is an apt analogy for what the criminal process may look like for most participants, who do not care about the structure or what it offers by way of imperious condemnation and just punishment, but just want to take what they can get and get out of it as fast as possible.

Until we get to a point where we can address the structural constraints, are performative bail hearings as good as it can get?