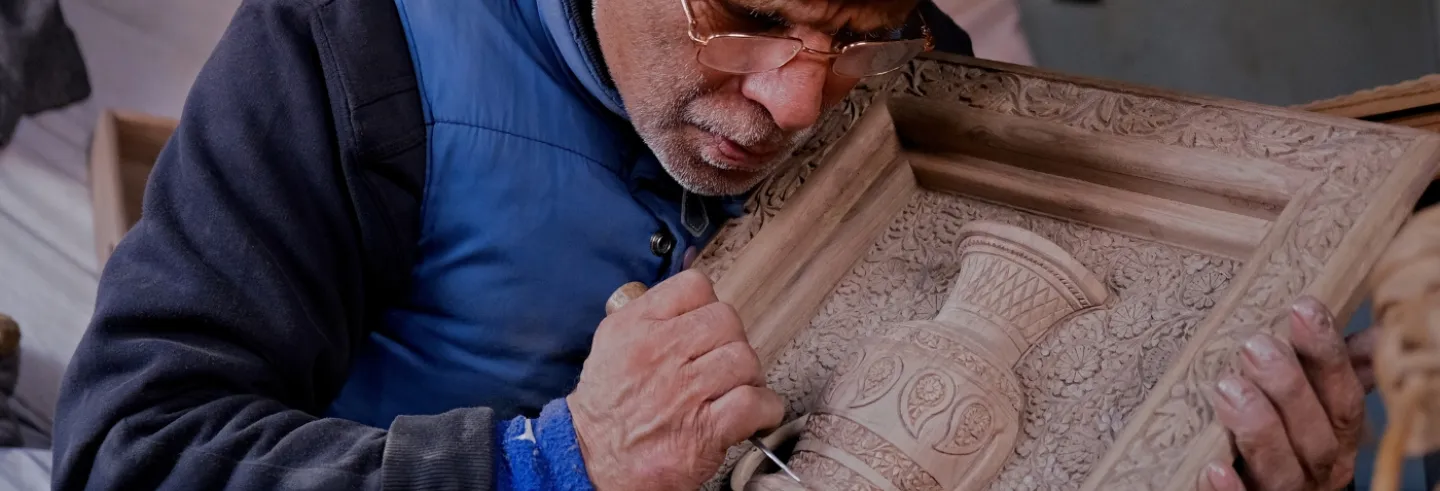

In the congested lanes of in Narwara, Srinagar, a deaf-and-mute artisan, Muhammad Yousuf Muran, continues his half-century old routine of carving wood sculptures.

Muran is the last generation of his family to make the sculptures. He sculpts at a 200-year-old shop that his father and grandfather worked from, six days a week, from morning to evening. He takes a break only on Fridays, to attend congregational prayers at the Dargah Hazratbal shrine.

Muran’s elder son, Saqlain Yousuf Muran, speaks on behalf of his father. Muran began his craft when he was just five years old. Now he is 55. “Though my father might not be able to speak and hear, his art is unmatchable. He has got a sharp and quick mind and is presenting his art in a way, which is beyond imagination,” Saqlain says.

It is a task that requires skill and patience. “It takes almost 15-16 days to make a single small sculpture,” Saqlain says.

Muran’s repertoire includes relief carvings, chip carvings, animals, and birds. At his workshop are piled up depictions of a herd of elephants trotting on a field, an eagle spreading its wings, an elderly Kashmiri man puffing at a traditional hookah, and a family enjoying tea from a samovar in rural setting.

At the family’s showroom, located along National Highway in Lethpora, Muran’s sculptures of a huge lion and the historical Jamia Masjid attract of customers. His representations of kangris – the traditional firepot – and samovars sell the most.

Muran is the last in his family to carve wood. The newer generation is focused on selling the products. The internet has provided them a means to get clients from outside Jammu and Kashmir, in India and across the globe, expanding the market for these elite products.

This has helped them break from the past, when artisans were exploited by traders.

“The sculptures of my father and his elder brother late Abdul Ahad Muran were being sold at the high-cost in the market, but they were being given only peanuts. This way, our elders and the main artisans, who should have received the praises and the appreciation have been ignored, neglected and exploited as well,” Saqlain says.

Muran’s nephew, Mudasir, who runs the showroom, laments at the state of patronage: “It is not an easy task to learn this art and skill, especially when there is no government support, which could have helped in ensuring better livelihood to the artisans.”

“The lack of government support has reduced the artisans to a hand-to-mouth situation.”