Electoral politics has come full circle in Jammu and Kashmir. In the state assembly election held in 2014, the National Conference-Congress coalition had lost power. But after a decade of upheaval, the alliance will form a government again.

The National Conference swept the Kashmir Valley and the Congress won all but one of its seats from there. Yet, both parties have a blemished record in the region. Both stand accused of cynical manoeuvres that are seen as betrayals in Kashmir, from signing accords that outlawed the popular demand for self-determination to allegedly rigging elections in 1987. Both parties have presided over large-scale human rights violations as armed conflict spread after 1989. Why, then, this return to the old status quo?

As one political observer put it, Kashmiris voted to be equal citizens again, to have the same basic rights assured to people in Maharashtra or Karnataka.

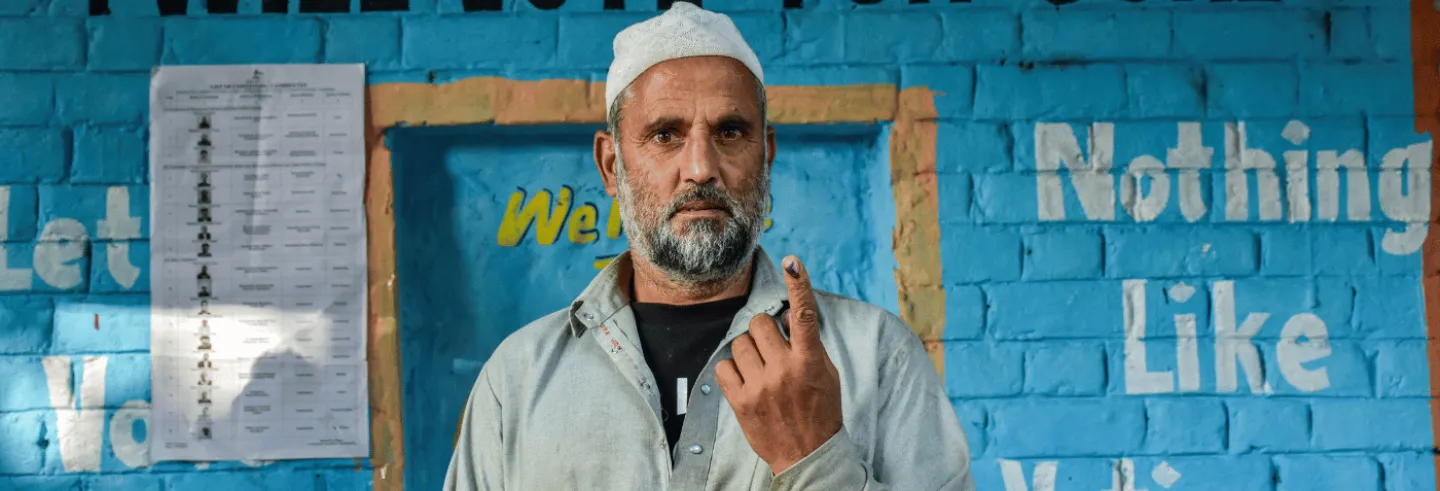

If the Lok Sabha verdict in Kashmir may be read as a protest against the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led central government, which stripped Kashmir of statehood and autonomy under Article 370, the assembly election result reflects more sombre calculations. This was not necessarily a verdict on Article 370 or some other political issue, say observers in the valley. This was a pragmatic vote for survival. As one political observer put it, Kashmiris voted to be equal citizens again, to have the same basic rights assured to people in Maharashtra or Karnataka.

Restoring the Ecosystem

As many in Kashmir like to say, assembly elections have always been about survival. Local leaders who entered the fray were looked on with suspicion and regarded as having made political compromises with Delhi. At the same time, they formed an ecosystem where the immediate needs of daily life could be met.

Despite the central government’s jubilation over the voter turnout in these polls, it was not out of the ordinary. Turnouts for assembly polls in Jammu and Kashmir have hovered just above 60% since 2008.

Valley-based parties asked for votes on quotidian issues—bijli-sadak-pani (roads-water-electricity) and a nebulous cache of economic promises that fall under the term “development”. There were other tacit promises, of quick fixes and negotiations that made life easier. For instance, there was the promise that a government job or a medical seat that could be obtained through political connections.

As Kashmir entered years of turmoil, it also saw widespread arrests. Local parties built pockets of support by pledging to mediate with the police for the release of arrested youth.

For years, Kashmiris set aside ideological issues and weathered boycott calls by the separatist leadership to vote in assembly elections. Despite the central government’s jubilation over the voter turnout in these polls—projected as a success of the BJP’s Kashmir policy, which has ensured a happy return to electoral politics—it was not out of the ordinary. Turnouts for assembly polls in Jammu and Kashmir have hovered just above 60% since 2008. This year, without boycott calls, the state saw a turnout of 63.9%, which was only marginally lower than the 65.9% recorded in 2014.

Still, there was an undercurrent of urgency to the poll campaign this year. After August 2019, when Jammu and Kashmir became a union territory administered by bureaucrats appointed by Delhi, the old ecosystem that had ensured day-to-day survival disappeared. In half a decade of central rule, Kashmiris felt themselves being reduced from citizens to subjects. As local leaders went back to the voters, it was clear that the meaning of survival had changed.

By showing its willingness to return to the electoral fold, the Jamaat hoped to reverse the UAPA ban imposed on it in 2019. A cleric known for galvanising the 2016 protests contested from jail.

This was reflected in both rallies and elections manifestos, where the emphasis shifted from bijli-sadak-pani to the promise of securing basic rights. Most parties promised to petition security agencies for the release of political prisoners. Even the National Conference claimed it would repeal the Public Safety Act, a stringent preventive detention law passed by its own government in 1978.

Other promises read like a catalogue of disempowerment faced by Kashmiris over the last five years—halting the summary dismissal of government employees, stopping the harassment of ordinary citizens on highways, and easing the process of passport verification, which had become a form of bureaucratic punishment and placed severe restrictions on freedom of movement.

People were tired of dealing with bureaucrats, said a resident of South Kashmir. Voters chose to restore the old ecosystem despite its flaws.

Fear and Coercion

Of course, these elections were not always a matter of democratic choice. Fear and coercion, working at different levels, have been a silent driving force. Participating in the poll process, many hoped, would bring some reprieve from the government crackdown of the last five years. Apart from political leaders, hundreds of civilians have been held under the Public Safety Act (PSA) since 2019. Others face terror charges, for offences real and imagined, under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). Jammu and Kashmir accounted for 36% of all UAPA cases in the country between 2020 and 2022.

A public spirit pushed many candidates into the poll fray, starting with the independents backed by the Jamaat-e-Islami, which had not contested an election since 1987. By showing its willingness to return to the electoral fold, the Jamaat hoped to reverse the UAPA ban imposed on it in 2019. A cleric known for galvanising the 2016 protests contested from jail. Others who stood for the election had relatives in prison.

Participating in the poll process, many hoped, would bring some reprieve from the government crackdown of the last five years.

Such compulsions may also have driven the electorate to polling booths. A lawyer in South Kashmir said those with relatives in jail or under the government scanner felt pressured, explicitly or otherwise, to vote. In North Kashmir’s Sopore, the fathers of two militants appealed to their sons to return home. At the same time, they cast their vote and urged others to follow suit.

It is telling that in the run up to the assembly poll, the Election Commission specifically warned against the preventive detention of political figures. Anecdotal evidence suggests detentions did take place in certain places, mostly of ordinary citizens. Often, they left no documentary trace, with men picked up and kept in police lock-ups for a few days or weeks.

Most had a police record, said the lawyer from South Kashmir—maybe an old first information report (FIR) or a history of detention under the PSA. But some did not. They were merely branded as “trouble makers” and locked up. In some cases, political participation could be a get out of jail free card. Many with FIRs against them escaped detention by joining a political party, the lawyer observed. Others with similar FIRs were not spared.

The towns, which were the ideological hubs of the separatist movement, have historically stayed away from elections. For the villages, staying away may be risky.

Such detentions are not new. Police sweeps take place before every major event in Kashmir, from elections to independence day functions and galas like the G-20 tourism meet held in Srinagar last year. But they do call into question the claim that these were free and fair elections.

A map of voter participation may reveal the silent pressures. On the whole, participation was higher in rural areas than urban ones—turnouts were below 50% in the towns of Sopore and Baramulla and below 30% in Srinagar. This is a trend seen in states across India. Voting is higher in rural areas, where citizens often have to rely on legislators to meet their needs. This is true of Kashmir as well, but there is another difference.

The towns, which were the ideological hubs of the separatist movement, have historically stayed away from elections. For the villages, staying away may be risky. In frontier districts, lives and livelihoods are closely entwined with the security presence. Those who do not vote risk being branded “anti-national”.

In the districts of South Kashmir, densely networked with security camps, there have always been rumours of army diktats to vote. These rumours surfaced as recently as the Lok Sabha election in May, said the lawyer. He added, however, that he had not heard of any explicit diktats before the assembly poll.

Incremental Gains

Many attribute the election result to the Kashmiri voter’s ability to adapt to circumstances. In the Lok Sabha election, National Conference vice president Omar Abdullah was defeated by Engineer Rashid, an independent candidate who contested from jail. It registered a deep-seated anger against traditional Kashmiri parties that had been a part of the status quo till 2019. This time, Abdullah is set to be the chief minister.

Kashmiris heading to the polling booths last month made a cool-headed choice. They could not afford to split the vote in the Valley, allowing the BJP to form a government. There were to be no experiments with independent candidates, many of whom were rumoured to be BJP proxies. They also rejected the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), under fire for tying up with the BJP after the 2014 assembly poll.

A vastly diminished assembly will not have the power to bring back autonomy … let alone tackle the larger Kashmir dispute. But many who voted see it as a battle of incremental gains to reverse the disempowerment of August 2019.

A shrewd public has little hope that this legislative assembly will be able to fight larger battles. Shortly before the election was held, the centre beefed up the powers of the lieutenant governor, who will have sway over the police, public order, and bureaucratic appointments.

A vastly diminished assembly will not have the power to bring back autonomy under Article 370, let alone tackle the larger Kashmir dispute. But many who voted see it as a battle of incremental gains to reverse the disempowerment of August 2019. It may be the basic rights of citizenship today, statehood tomorrow, and then other victories.

Ipsita Chakravarty is a writer who has reported widely on Kashmir.