One of the seminal events in the history of the Indian left was the split in the Communist Party of India (CPI) in 1964. Multiple, entangled strands contributed to the splintering of the party: ideological, political, organisational disagreements, and several conjunctural factors. In a nutshell, 32 members of the National Council of the CPI accused the dominant faction of the party of being reformist, rather than revolutionary, and an appendage of the Indian National Congress.

In left politics, allegations of reformism have a profound ideological import and a serious value judgement of the path proposed by the reformers – their faith in and compromise with existing institutions and political parties dominated by middle and upper middle-class leaders who are seen to be in cahoots with big business and big landlords – to bring about progressive change in the lives of all peasants and workers. Unlike the so-called reformers, the revolutionaries believe that only a rupture, which dramatically transforms the existing political and economic order, can rejuvenate the lives of workers and peasants.

A reformist or revolutionary outlook not only shapes the way they perceive the world around them, but also their interpretation of its history and their vision for its future. It influences one’s analysis of the structure that needs changing and the type of collective action that would transform these structures. Therefore, ideological disputes are not merely badges of difference – in the case of the left in India these frictions have led to multiple splits and the creation of distinct apparatus for separate left parties such as trade unions, student unions, and peasant unions. This makes any desire by hopefuls for the merger or unity of communist parties in India a pipe-dream.

The CPI struggled to come to terms with the variance in the Congress as political party and the Congress that captured state power and exercised it.

Instead of unity, the preferred practice is alliance of the leftist parties based on common minimum programmes and political tactics. The tactics include alliances against a common adversary – with the Congress party against British imperialism, with British imperialism against fascism during the Second World War, and in the postcolonial period with left parties against the Congress party, or with the Congress against parties advocating Indian versions of fascism, with right-wing parties against the Congress party in the 1970s and 80s or with the former against regionally dominant parties, such as the Trinamool Congress in the 2010s.

Short term tactics could and did change, for some observers of the communist parties exasperatingly and frequently so, but long-term goals remained more consistent. For the communists, it entails a critique of political economy or capitalism and of the state and classes that uphold it, a commitment to build an alternate coalition of classes with workers and peasants at the forefront who would capture the state and bring about changes to the economy and society.

Transforming politics and society

This initiates another puzzle: how would the transformation from capitalism to socialism come about? Would it cleave to the path of parliamentary democracy as the Communist Party of India committed to in the postcolonial period earning the sobriquet ‘parliamentary left’ from Maoist groups of the late 1960s or will violence play a role in this transition? The questions elicited and continues to invite further debate and discord at the heart of which is a conundrum: can parliamentary democracy on the one hand, or violence that skirts electoral politics on the other, achieve the revolutionary transformation envisaged by communists?

The question of revolutionary transformation of politics and society has been debated by Indian communists since the 1920s. Those debates have led to factional disputes, changes in tactics, and splits in the party. In what is to follow, we will revisit the 1964 split in order to understand the issues that led to the fissuring of the communist movement sixty years ago. Some of the issues that were debated then – the relationship of the communists with the Congress party, CPI’s stance towards China, the role of American imperialism, and the nature of Indian capitalism remains relevant today, too. Such an exercise may help us understand why the split occurred and became entrenched and instead of a merger, the rapprochement took the form of strategic alliances of the united left front.

The 32 members at forefront of the split were deemed ‘lefts’ and ‘leftist’ by the so called ‘right’ at the time. Amongst them were luminaries of the future Communist Party of India (Marxist) such as P. Sundarayya, M. Basavapunniah, E.M.S. Namboodripad, Jyoti Basu, and Harkishan Singh Surjeet. To add more fuel to the already raging fire between the two factions, the chairman of the CPI at the time, S.A. Dange, was accused of being an informer of the colonial British government. Dange vehemently denied the allegations; some of the leaders of the splintering group could not be convinced otherwise. Moreover, the documents on which the allegations were based disappeared from the National Archives of India and the issue was never resolved, satisfactorily.

A tricky alliance

Let us unravel some of the strands leading to the split. The CPI’s relationship with the Congress Party had been a source of tension and intense debate since the 1920s. At the root of these tensions was the difficulty Indian communists had (and arguably continue to have) in dealing with Congress. The CPI struggled to come to terms with the variance in the Congress as a political party and the Congress that captured state power and exercised it.

As a party, the communists could find common cause with the Congress, as they did in their anti-colonialism or in raising the issues of workers and peasants which both parties were mobilising in the 1920s and 1930s, even when they differed ideologically on other issues. But when the Congress held political power, the communists were frequently at the receiving end of the might of the government.

This put the CPI in a bind: should it align with the Congress in its anti-colonial endeavours or critique it as a bourgeois party that favoured its own class and abandoned the interests of workers and peasants when it exercised power. Under the guidance of the Communist International in 1928, the CPI declared the Congress to be ‘bourgeois nationalist’ and its leader M.K Gandhi was branded ‘counter-revolutionary.’

The Communist International (Comintern) was created in 1919 to universalise the Bolshevik revolution. Yet, the Comintern’s trenchant assessment of the Congress did not square with the reality of Indian communist presence in the party. The British government’s aversion to the global spread of communism meant that many communists were tried for sedition and jailed. Therefore, some communists joined the Congress.

The CPI itself was banned in 1934. At this time, many more communists became members of the Congress party and aspired to change it from within by aligning with progressive groups in the party. They formed a group called the Congress Socialist Party that operated inside the Congress. This group included EMS Namboodripad, P Sundarayya and A. K. Gopalan, the future leaders of the CPI and eventually the CPI (M). The Comintern too changed tack and favoured a united front against the colonial government in the 1930s. In the process, they fostered the ideological justification for a strategic alliance between the communists and the Congress.

Global events had flummoxed the Indian communists and they found it difficult to synthesise their commitment to anticolonial nationalism on the one hand with the defence of global communism and the defeat of fascism on the other.

This honeymoon, if it can be termed that, was short lived. When the Congress Party formed ministries in eight out of 11 provinces following the elections in 1937, India’s leading businessmen such as G.D. Birla exulted, and some Indian businesses benefited from Congress’s swadeshi policies. In late 1938, the Congress ministry in Bombay passed the Bombay Trade Disputes Act which inaugurated new rules for registering trade unions that made the legitimacy of a union dependent on the approval of business owners. The act also recommended a jail term of six-months for strikes deemed illegal.

This business friendly and anti-labour act was a blow to leftist unions already reeling from the ban on the CPI and exacerbated the tensions between the Congress government and communist labour leaders. The Congress as a party provided an umbrella for socialists of various hues, including communists. But as party of governance, the umbrella frayed exposing the communists to the vagaries of state power, a state that had a short fuse for dissent.

World War II deepened CPI’s quandary. In the first few years, the left opposed the war and the Congress was not averse to supporting it even though Indians had been dragooned into it without consultation or consent. The Congress would have participated in the war wholeheartedly had the colonial government promised independence after the war.

Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, and Japanese entry into the war at the end of that year, changed the war for Indian communists. They did a volte face and reversed their anti-war stance – just like other communist parties around the world. The CPI now supported the war in order to defend the exemplar of global socialism, the Soviet Union.

In effect, the CPI became an ally of the colonial Indian government and the state lifted the ban on the party. The Congress on the other hand launched the Quit India movement in 1942, which was now opposed by the communist members in the Congress, but supported by conservative leaders in the party such as Vallabhbhai Patel. Global events had flummoxed the Indian communists and they found it difficult to synthesise their commitment to anticolonial nationalism on the one hand with the defence of global communism and the defeat of fascism on the other.

Dealing with Independence

The end of colonialism in India heralded the transfer of power to the Congress party. This did not simplify CPI’s conundrum. Just before independence, in 1946-47 when the Congress led provincial governments, and immediately after Independence, the communists encountered the weight of the Congress-led State apparatus in a slew of agrarian movements: Bengal (Tebhaga movement), Telangana, Thanjavur, Bihar, Malabar, and the Warli agitations in the Bombay province. Its cadre also faced repression in urban centres such as Bombay and Kanpur. Its long history of alliance with the Congress party in anticolonial movements had to confront the reality of repression of peasant and urban movements in late colonial and postcolonial India.

It was in this context that the CPI held its second party congress in 1948 to reflect on some of the positions it had held during and after the war. It arrived at two conclusions: the CPI had underestimated the power of imperialism during the war years and had concluded, wrongly, that the defeat of fascism in Europe would also end imperialism all over the world. The second insight was that the structures of imperialism remained resilient despite the demise of colonialism. The import of the argument was that Congress rule was a) a continuation of colonial rule and b) India was still under the sway of Euro-American imperialism.

Another controversial point was the promotion of peaceful transition from capitalism to socialism, especially in capitalist countries.

This dramatic conclusion - that independent India may not be completely sovereign after all and that colonial power had transmogrified into Congress rule - by leaders such as BT Ranadive, elicited furore and debate within the party. This debate resonated in the 1964 split and was invoked by Basavapunniah as evidence of unresolved issues from 1948 to 1950, the years Ranadive was the general secretary of the party. Ranadive also became a leader of the CPI (M) after the CPI split in 1964.

An invocation of revolution in independent India entailed deliberation on the path to a radical social, economic, and political rupture. How would a revolution come about: through an armed upsurge or via democratic and constitutional means?

The CPI’s involvement in urban and rural movements had garnered a strong political base in various parts of India which could translate into electoral victories. In the early 1950s, the party committed itself to parliamentary democracy and in the first Indian election in 1951-52 emerged as the largest opposition party. In the second election in 1957, the CPI was again the largest opposition party and in Kerala became the single largest party and formed the government under the leadership of EMS Namboodripad, with the support of five independent legislators. The Kerala government though was dismissed by the Congress-led central government in 1959 on the pretext of a deteriorating law and order situation in the state.

Global winds

Despite the Congress government’s machinations in Kerala, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was not unpopular amongst many communist leaders particularly owing to his policy of non-alignment, his advocacy of economic planning and his openness to Soviet help in establishing big industries in India.

But the global conjuncture changed again in late 1950s. It set in motion processes that led to the split in CPI. The policies of post-Stalin, Cold War Soviet Union yielded three documents that influenced both world and Indian Communism. These documents, published by the self-confessed vanguard of world socialism, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, carried ideological and political heft. It ignited a debate in communist parties of the world at that time.

The first of these was Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s secret speech to the Communist Party of Soviet Union in 1956, decrying the cult of personality around his predecessor, Joseph Stalin. The cultivation of the cult and the celebration of an individual as an all-knowing hero was against the principle of Marxism-Leninism, he said. Khrushchev’s critique of Stalin was declared revisionist by some communists and dismissed by China’s Chairman Mao Zedong who was consciously deploying the cult of personality around him to keep the Chinese bureaucracy in check. Khrushchev’s speech was perceived as an oblique critique of Chinese communism and contributed to the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s. The CPI supported the Soviet critique of the cult of personality.

The war aggravated the CPI's ideological and political fissures. Its longstanding commitment to Indian nationalism and its history of aligning with the Congress party and Nehru as an ally in social democratic struggles got entangled with the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s.

The second document was a 1957 declaration in Moscow of twelve communist and worker parties across the world. This document pitched for peaceful co-existence of capitalism and socialism even as it believed that socialism was superior to capitalism. It also advocated for the coexistence of imperialist, socialist, and postcolonial nations in order to advance ‘world peace.’

The immediate context in which this document was finalised was the threat of nuclear war heightened by the Cold War. The signatories felt that a world war, with nuclear weapons, would extinguish the possibility of peace. But this stance of the Soviet Union was again perceived to be revisionist by China because it seemed to focus excessively on Soviet concerns in the Cold War and not the interests or realities of world communism at the time.

The third document was a 1960 statement signed by the communist and workers’ parties of 81 countries, prescribed peaceful economic competition between socialism and capitalism even as it underlined the decadence of capitalism and the preeminence of the socialist economic system. In order to develop socialism in former colonial countries, the document emphasised universal socialist principles, that had been worked out in the Soviet Union and other European countries. In order to avoid the charge of ahistoricism or modular application of socialist principles, it advised communist parties around the world to be attentive to the ‘historical peculiarities’ of each nation. But at the same time, it warned against ‘undue emphasis’ on national particularities.

The document was notable for a few other points too. One of them was its re-estimation of social democratic parties, which had hitherto been labelled revisionist and reformist. The statement proposed that social democrats were allies of the communist parties in combating the scourge of nuclear war, in improving the living conditions of working people, and in tackling fascism. The implication of the statement was that the Congress party could be a social democratic ally particularly if it could be steered down that path by socialist allies within and outside the party.

Another controversial point was the promotion of peaceful transition from capitalism to socialism, especially in capitalist countries. It warned against dogmatic, sectarian and “Leftist, adventurist” action in revolutionary struggle which prevented adherents from understanding the changing situation and fomented the splintering of communist parties. This was seen as an oblique critique of China and of global communists who sympathised with Chinese communism.

The Chinese question

What made matters worse for the CPI was the border dispute and the eventual war between India and China from 1959 to 1962. The two governments, founding pillars of the non-aligned movement, could not settle claims and counterclaims to territories demarcated by the colonial era McMohan line. The dispute led to war in October and November 1962.

The war aggravated the CPI's ideological and political fissures. Its longstanding commitment to Indian nationalism and its history of aligning with the Congress party and Nehru as an ally in social democratic struggles got entangled with the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s. Moreover, some party leaders felt that the time was ripe for a stringent critique of the Congress and a reassessment of capitalism and the nature of the Congress-led State in India at the time.

The CPI almost split in 1961 at the Vijaywada party congress over these issues. That split was avoided. But the party weekly National Front demonstrated that its top leadership was more attuned to the Soviet line in the Sino-Soviet split and committed to Indian sovereignty in the face of war.

Some of the ideological differences that fuelled the original split – the debate on China, the nature of Indian capitalism and the Indian State, Euro-American imperialism, and the viewpoint on the Congress party – continue to animate differences.

After the end of the 1962 war, the tensions that had simmered but had been pushed aside, exploded in the open. Basavapunniah demanded that the CPI revisit the post-Stalin Soviet statements for a detailed discussion of their implications. He chided “the display of ‘affection’ to Soviet communism and hatred for the Chinese version” (1963). S.A. Dange, who was the chairman of the CPI at the time, agreed that the party had been critical of the Chinese communists but wanted inner party discussions to be within the parameters of its existing procedures and its organisational principles of democratic centralism. This implied that the majority of the dominant faction - deemed ‘right’ by Basavpunniah and his associates - would play a decisive role in addressing any dispute.

By 1964 the so called ‘left’ and ‘right’ factions offered their respective programs to facilitate ideological and political discussions within the party. Namboodripad proposed a third - castigating both factions for not paying adequate attention to the international ideological situation: “the Indian revolution is not taking place in a vacuum,” he exhorted (1964). He also reprimanded the factions for not adequately tracing the continuity between the British colonial regime and Congress party rule. Moreover, he rebuked the ‘right’ for issuing “the certificate of good conduct” to the Congress party and varnishing its anti-people and undemocratic activities, which included the dismissal of the Kerala government in 1959.

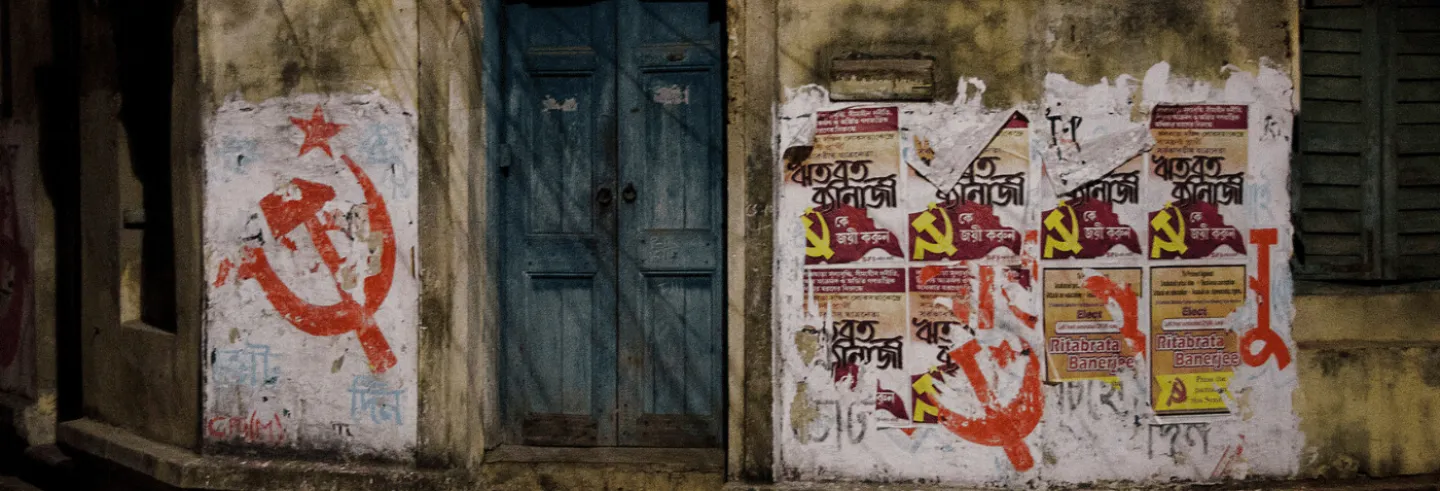

By April 1964 the split was apparent and by the end of that year it was official. Both the factions organised rival seventh Congresses – the left faction at Kolkata in early November and the right faction in December at Bombay. Both claimed to be the original CPI but the Election Commission of India proclaimed its inability to recognise two CPIs.

Living together separately

In early 1965, at the time of the midterm election in Kerala, the left faction was recognised as the CPI (Marxist). Both the CPI and CPI (M) contested the elections separately; their attempts to form a left front based on a common minimum programme collapsed when factional disputes broke out again. One of the points of contention, again, was their stance on the Congress Party. But the two parties did manage to carve out ‘special arrangements’ amongst themselves on a few seats in that election. The CPI (M) emerged as the single largest party in 1965 and was the dominant left party in Kerala. It was in the 1967 elections in Kerala that the CPI and CPI (M) formed a united front, won the election and set the tone for future left alliances in India.

Despite periodic demands from some of their supporters, the CPI and the CPI (M) never merged. In fact, the CPI (M) fissured further with the emergence of the Naxalbari movement. What has kept the parties apart is the feasibility of merging two parties with their own institutional apparatus into one entity. But some of the ideological differences that fuelled the original split – the debate on China, the nature of Indian capitalism and the Indian State, Euro-American imperialism, and the viewpoint on the Congress party – continue to animate differences.

New historical developments have added further complexities – the ascent of the Bhartiya Janata Party, the transformation of the global political economy, the demise of the Soviet Union and the rise of China as the dominant model of global communism, and transformation of the Congress Party from a social democratic party advocating secularism to the votary of neoliberalism and soft Hindutva, continue to exercise both communist parties and shape their decision to align on a common programme, but remain separate entities. That model of political alliances based on a common minimum programme have also played an influential role in the Third Front politics of the 1980s and 90s, the United Progress Alliance of the 2000s, and the INDIA bloc of the 2020s.

Juned Shaikh is an associate professor of history at University of California Santa Cruz. He is the author of Outcaste Bombay: City Making and the Politics of the Poor (OrientBlackswan, 2021) and is working on a book on the Indian Marxist Gangadhar Adhikari.