In almost every textbook on climate change, the discovery of the greenhouse effect is attributed to John Tyndall, an influential Irish scientist who did most of his work in the Royal Institution of Great Britain. Through his experiments, reported in 1859, Tyndall showed how the concentration of gases such as carbon dioxide could lead to atmospheric heating, resulting in global warming.

Three years before Tyndall, an American woman scientist had presented a pioneering experimental result that showed how gases influenced heating in the atmosphere.

That scientist was Eunice Newton Foote.

***

Foote was remarkable not only because she made outstanding scientific discoveries related to climate change (almost forgotten) but also for other reasons. She was an inventor with patents to her credit. She was also a prominent women’s rights activist in the United States in the movement’s early years.

Foote attended Troy Female Seminary, the first institution dedicated to providing higher education to women in the United States. Established in 1821 by Emma Willard, a liberal and scientific education was imparted simultaneously at Troy. The school encouraged its students to study philosophy, mathematics, and languages. It facilitated laboratory experimental training, the foundation for physical sciences.

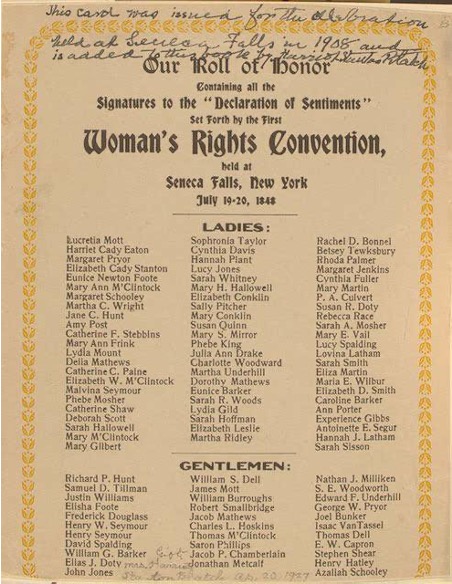

Troy was "an important source of feminism and the incubator of a new style of female perspective,” writes Anne Scott (1979), who has researched the institution. Amongst Foote’s cohort in the school was Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who would go on to lead the first women’s rights movement in the United States (Wellman 2004).

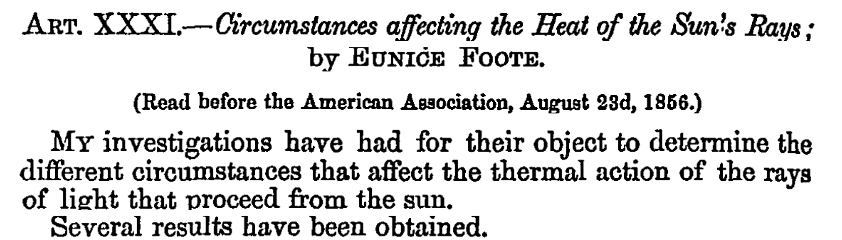

Foote’s scientific work was published in two research papers, presented to the American Association Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meetings in 1856 and 1857. The first paper was related to the heating of gases by the sun, and the second one was associated with the source of electric excitation. These papers were likely the first physics (excluding astronomy) research papers published by an American woman.

Although Foote had independently performed her work, she could not present them herself at the AAAS meetings, which like many other institutions of the time, did not include women presenters. Her first paper read by Joseph Henry, the first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. (In the same meeting, a paper by Foote's husband, Elisha Foote, was presented by the author himself.)

Ortiz and Jackson (2020) have written about Foote’s paper in historical context. Her first paper, ‘Circumstances affecting the Heat of the Sun’s Rays’, investigated the connections between atmospheric gases and the radiant heat due to the sun’s rays falling on Earth. Thanks to contemporary records of New York Daily Tribune (1856), which highlighted Foote's paper presented by Henry, and the subsequently published records in Annals of Scientific Discovery (1857), we get a summary of her experiments, as discussed in the AAAS meeting:

Thirdly, a high effect of the sun’s rays is produced in carbonic acid gas. One receiver being filled with carbonic acid, the other with common air, the temperature of the gas in the sun was raised twenty degrees above that of the air. The receiver containing the gas became very sensibly hotter than the other, and was much longer in cooling. An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a much higher temperature; and if there once was, as some suppose, a larger proportion of that gas in the air, an increased temperature must have accompanied it, both from the nature of the gas and the increased density of the atmosphere. Mrs. Foote had also tried the heating effect of the sun’s rays on hydrogen and oxygen, and found the former to be less, the latter more, susceptible to the heating action of sunlight.

There are a few points to be emphasised here. First, carbonic acid is what we now know as carbon dioxide. Second, Foote's work connects carbon dioxide to the earth's temperature. Her inference was to show that the presence of carbon dioxide and its increasing concentration can directly increase the temperature. Foote did not address why and how this increase in temperature occurred, but her experiments revealed the connection.

Three years later, Tyndall made elaborate measurements with a more sophisticated set-up to put this observation on a solid footing. His systematic study further enhanced our knowledge of the greenhouse effect. Tyndall’s work is today credited as the most critical observation related to the greenhouse effect. But we must acknowledge that Foote had not only thought about heating of atmosphere in the presence of gases but also demonstrated it using simple equipment.

***

Outside her her scientific work, Foote was a progressive, forward-looking woman who actively participated in debates and discussions about women’s rights. She was an active participant and signatory to the iconic Women’s Rights Convention held in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York, and led by her fellow Troy alumna Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She and other colleagues played a vital role in editing and publishing the final version of the convention proceedings.

The Seneca Falls convention played an essential role in initiating a regular women-centric convention, which continued regularly until it was disrupted by the American Civil War in 1861 (Wellman 2004). Its international influence motivated other countries to organise women's rights events, especially in Europe.

Notably, while registering her inventions, Foote took the initiative to publish patents in her name, which was unusual for her time. She may also have collaborated on some of her husband's inventions and have filed a few patents in his name .

Foote’s life story also reveals how difficult it was for women to do scientific research and get the credit it deserved. Even in the upwardly mobile, affluent society in which she lived, her contributions were not highlighted. Rachel Brazil captures this notion well, saying a “definitive photograph or drawing of Foote is still to be found.” Her contributions to climate change research have only been rediscovered recently.

There may be many more examples of people, including women from the colonial era, whose scientific discoveries and inventions have gone unnoticed. Science is objective and universal, but the pursuit of science and its reward system is not and depends on various parameters, including gender, nationality, and race. We should remember that there are many unsung people in science, and Eunice Newton Foote was one of them.

G.V. Pavan Kumar is a professor of physics at the Indian Institute of Science Education & Research, Pune. The views expressed are personal.