I. Context

On 8 July 2024, responding to a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) on mandatory menstrual leave for students and working women, the Supreme Court asked the Centre to frame a model policy on menstrual leave after consulting all stakeholders. It, however, expressed concern that it could have an adverse impact on women’s employability. It is noteworthy that the same PIL was not accepted by the Supreme Court in 2023 on the grounds that the matter fell within the policy domain.

The question of paid menstrual leave had sparked a debate (see here and here) in December 2023 too, when Smriti Irani, the then Minister of Women and Child Development, had stated in Parliament that the government did not plan to make menstrual leave mandatory at workplaces.

Should India make it mandatory to provide paid menstrual leave to women? Given India’s stage of development, such a policy would not only be ineffective, but it would also take the focus away from what is really needed—basic infrastructure and affordable menstrual products.

II. Band-Aid Solution

Benefits mostly privileged women

Most of India’s female workforce is either self-employed or in casual labour (unorganised sector). Only about 5% of working women are in regular employment, over half of whom do not have a written job contract or paid leave, or social security benefits (Employment Statistics in Focus 2023). Clearly, for more than 95% of working women such as agricultural workers, casual labourers, vendors, or domestic workers the policy would be only on paper.

Menstrual leave is not a new concept in India. Bihar in 1992 and Kerala in 2023 introduced menstrual leave policies for working women and students, respectively. But both only cover government employees and institutions.

Unfair burden on employers

India’s menstrual leave policy would most likely expect the employer to bear the cost of paid menstrual leaves. It would put an unfair burden on micro, small, and medium enterprises, the backbone of India’s economy, if there is no cost-sharing arrangement with the government or guardrails against misuse.

Globally, till date only eight countries have legally mandated menstrual leave and most have some guardrails to protect employers. For instance, Japan and South Korea offer only unpaid menstrual leave while Taiwan offers three days of menstrual leave annually with compensation at 50%. Spain allows only women who have paid into the social security system for six months to avail themselves of the leave with a doctor’s certificate. Zambia, Indonesia, Vietnam and Philippines do allow paid menstrual leave of one to three days but the implementation is inconsistent and their experiences have been mixed.

Deepen discrimination in hiring of women

Women who seek employment in India have to contend with patriarchal attitudes and the inherent biases prevalent in society. Mandating paid menstrual leave would deepen these biases and may adversely impact the employment opportunities of women in the formal workforce.

Lack of state capacity

Lastly, India’s policymakers (and judges in this case) often do not seem to consider the acute lack of state capacity while designing policies (Rajagopalan and Tarrabok 2019). Making it mandatory for companies to give paid menstrual leave would be difficult to enforce and encourage people to disrespect and flout the policy without fear of consequences.

III. India’s Current Approach

Research shows that providing better access to menstrual hygiene in workplaces and public areas is likely to increase women’s participation in the workforce (Eaton et al. 2023). Currently, however, India’s infrastructure regarding menstrual hygiene is abysmal and it disproportionately impacts women engaged in sectors such as construction, street vending, domestic work, and app-based gig work (International Center for Research on Women 2021; Action Aid 2019). Even formal workplaces such as police stations, courts, and public sector banks have limited sanitation facilities for all employees.

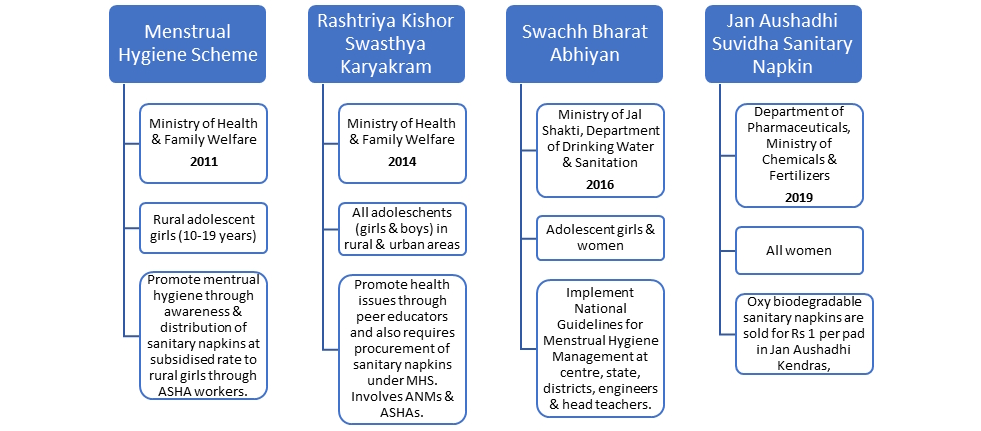

The union government has paid some attention to menstrual hygiene over the past decade and a half. Since 2011, various schemes (Figure 1) focusing on menstrual health and hygiene as well as building toilets have been framed. The Ministry of Jal Shakti drafted some National Guidelines for Menstrual Hygiene Management in 2015 as an integral part of the Swachh Bharat Mission guidelines. Recently, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare also drafted a National Menstrual Hygiene Policy, 2023, which is in the public domain for feedback. However, the implementation of these schemes is patchy. The schemes are targeted primarily at adolescent girls and young women with a focus on building awareness and distributing sanitary napkins.

Figure 1: Key Government Initiatives at the Central Level

A number of state governments have also launched schemes to promote menstrual hygiene such as Madhya Pradesh’s Udita Yojana, Karnataka’s Shuchi Scheme and Tamil Nadu’s federation of 60 self-help groups to produce sanitary pads. These initiatives, both at the centre and states, have improved menstrual hygiene. Now, 77% of rural women aged 15 to 24 years use hygienic menstrual products, up from 58% per cent in 2015-16 (NFHS IV and V).

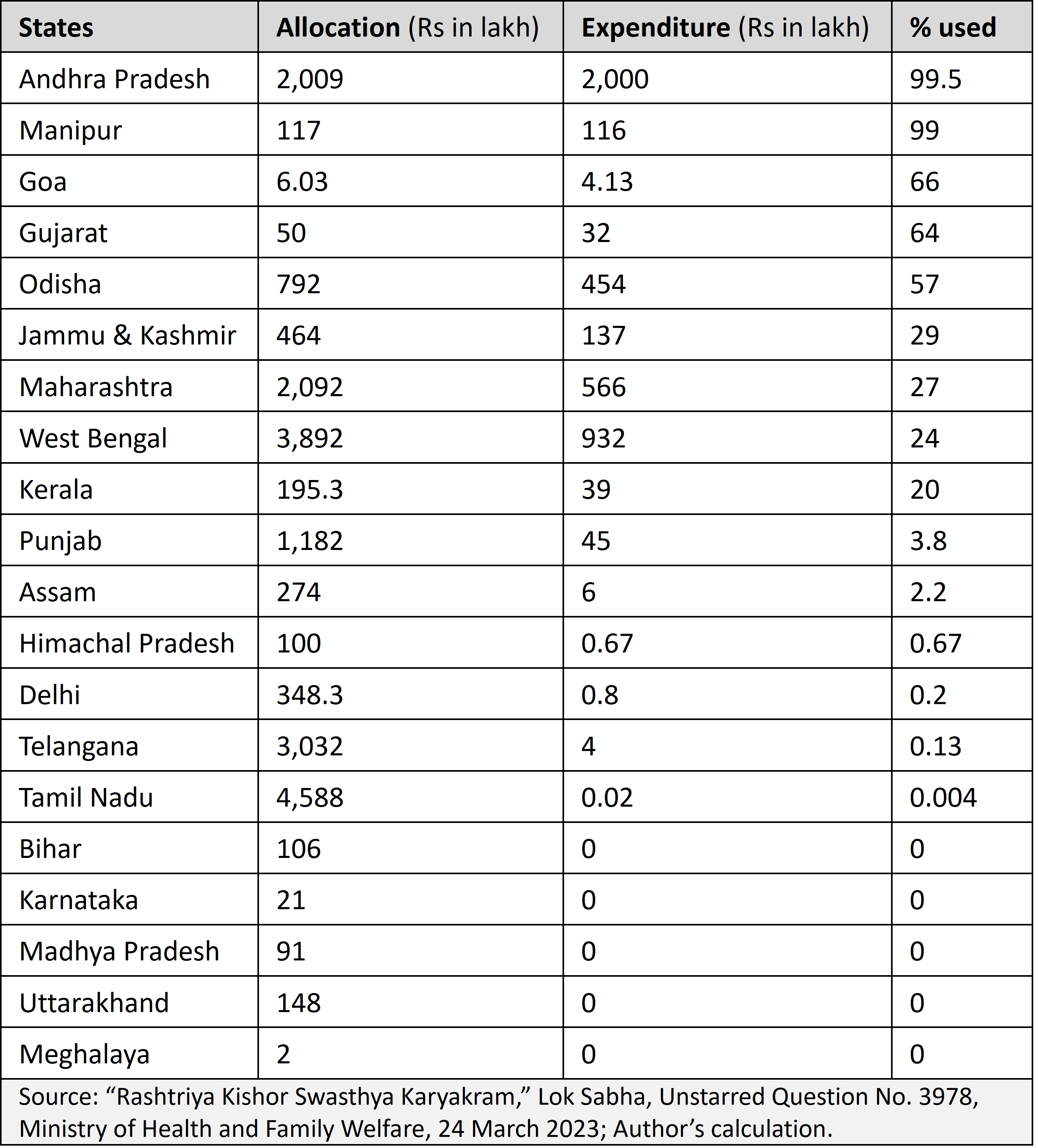

The implementation of government schemes, however, leaves a lot to be desired. Many states such as Assam, Punjab, and Himachal Pradesh only partially spend the allocated funds for menstrual hygiene schemes (Table 1) while states such as Arunachal Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Haryana, and Jharkhand do not have approved state programme implementation plans (plans proposed by the states and approved by the central government).

Table 1: Rate of Usage of Allocated Funds for State Programme Implementation Plans under the Menstrual Hygiene Scheme in Select States (2022-23)

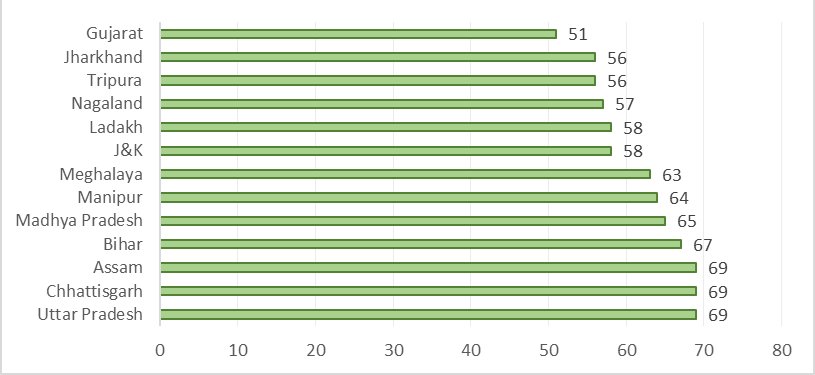

Although distribution of sanitary pads through various schemes has led to an increase in their usage, the use of cloth among women in some states is quite high. Figure 2 lists states where more than 50% of women used cloth during menstruation.

Figure 2: Use of Cloth for Period by Women Aged 15-24 years (in %)

There is a wide variation in use of sanitary menstrual products based on location (rural-urban), education, and income levels. Although the government schemes require frontline workers such as auxiliary nurse midwives and accredited social health activists to raise awareness and act as educators on menstrual health and hygiene issues, surveys have revealed that many of them have not received any formal training on menstrual health.

IV. Towards a New Policy

Inadequate infrastructure for menstrual hygiene management can limit women’s participation in the workforce. Although the Indian government has acknowledged this, a comprehensive and inclusive menstrual hygiene policy with a clear roadmap and resource allocation remains elusive. What would a comprehensive and inclusive policy entail?

In India’s context, the policy must ensure that all menstruators, irrespective of age, sexual orientation, location, income or education levels, have access to usable toilets, bathing facilities, affordable and safe sanitary products, and disposal mechanisms. This should be complemented with awareness programmes to break the stigma associated with menstruation, and with access to quality healthcare in case of any medical problems related to menstruation.

Some of these solutions have been mentioned in the Draft National Menstrual Hygiene Policy, 2023 (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare 2023) piloted by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. A culmination of standing committee recommendations and Supreme Court directives, it aims to ensure access to safe and affordable menstrual hygiene products and facilities such as clean toilets, and raise awareness of proper disposal practices. However, without a clear roadmap for implementation and provision for regular monitoring, whether these guidelines would translate to action on the ground remains debatable.

Improving the menstrual hygiene needs of girls and women is crucial if the government is serious about encouraging them to join the workforce. It would require the government to prioritise the following aspects.

1. Create a roadmap: The government needs to lay down clear goals and objectives for menstrual hygiene and create a detailed roadmap for attaining these goals. Both should be based on high-quality data about the menstrual hygiene habits of all menstruators, which could come from evaluation of existing schemes and programmes and through detailed feedback from the relevant stakeholders. The roadmap should include a detailed estimate of the financial and human resources required for its implementation. Regular monitoring and periodic evaluation should be built into the entire roadmap.

2. Build capacity of frontline workers: There is need to strengthen the capacity of frontline workers and influencers such as teachers, community health workers, and mothers. This could be done through regular training and equipping them with materials for raising awareness within the community.

3. Encourage development of low-cost, high-quality menstrual products: The government needs to support manufacturing of innovative menstrual products, which are environmentally friendly, low cost, and culturally appropriate.

4. Disposal of menstrual waste: In India, menstrual waste is mostly disposed by burning in local incineration or burying in the ground. Both are harmful to the environment. The government should brainstorm with non-governmental organisations (NGOs), the private sector, academia, and social enterprises to develop innovative solutions for waste disposal in an environment friendly manner.

5. Build usable toilets: Although the government has prioritised building toilets in schools and public places, there is still a large gap in the availability of usable and functional toilets in workplaces and public areas. The government should focus on not just building toilets but also ensuring that they have water, are connected to a sewerage system, and are cleaned regularly.

While the degree may vary, most women in India face significant structural barriers that hinder their participation in the workforce. A key barrier is the lack of provisions for menstrual hygiene management and the stigma attached to menstruation, which shames women into silence. If there is a concerted effort from all stakeholders to meet the menstrual needs of women, it would be a step in the right direction in the long road to women’s economic empowerment.

Kaushiki Sanyal (kaushikisanyal@justjobsnetwork.org; kaushiki.sanyal@gmail.com) is a Fellow at JustJobs Network.