Introduction

This year, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) chose the theme 'The Evidence is Clear: Invest in Prevention' to mark the International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking on 26 June. The UNODC’s focus on prevention is especially important for a post-colonial country like India, where strict laws targeting supply have been the primary approach to tackling substance (drug) abuse. A recent report by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment revealed that millions of citizens in India are dependent users of different types of substances and are in urgent need of treatment, while only 25% have access to standard treatment (Ambekar et al. 2019).

Passi (2019) stresses understanding the socio-ecological determinants of substance use to design any prevention or intervention strategy. Different models of substance use – for instance, the Social Learning Model and the Family Systems Model – also suggest that ecological factors play a significant role in pushing an individual to substance use (Carvalho and Garner 2019). However, our criminal justice system is more inclined towards punishing all “illicit” substance users (including dependents) rather than supporting them in getting access to adequate treatment.

We believe the existing substance use prevention and treatment policies designed at the centre, state, or even the district level are inadequate to respond to local socio-cultural realities.

The system has also been trying to change its public image. It is clearly trying to do so by increasing its visibility in various preventive efforts and community welfare programmes and showing its human side in times of disaster or pandemic (for example, during Covid-19 relief work). In addition to that, many state and district-level programmes are being organised to engage certain sections and communities. For instance, a Night Marathon was organised in January 2023 by the Ahmedabad police to engage with the city youth to tackle the increasing demand for drugs. Thus, several preventive efforts are being made at the upper level of the police organisation to alter the prevailing public image of the police.

However, what happens at the police station level with citizens contributes the most to the desired change. Local-level intervention efforts informed by the geographical context (cultural, economic, and political) increase the possibility of more focused and pragmatic action, along with community participation. Such efforts can contribute the most to the positive image of the police. This exercise can be an opportunity for a participatory process at the police station level. This article discusses a local-level substance use prevention initiative undertaken with the Gomtipur police station in Ahmedabad and recommends that grassroots workers and organisations attempt this model.

Vyasanmukt Gomtipur Abhiyan

On 27 September 2018, we rushed to the Gomtipur police station in Ahmedabad to register a case against a person who was fraudulently collecting money in the name of an 'RTE Scholarship'. Police inspector Chirag Tandel assured us that all legal procedures would be followed after an investigation. When he came to know that we worked on issues associated with substance abuse, he expressed a willingness to work on tackling the issue of alcoholism, which had been prevalent in the area after textile mills were shut.

The discussion concluded with a promise to prepare a practical action plan to support substance dependents who wished to get rid of their addiction. On 29 September, we called a meeting of key stakeholders, such as the Assistant Commissioner of Police (ACP), municipal councillors, and community and religious leaders, where we presented an action plan entitled the Vyasanmukt Gomtipur Abhiyan (VGA). 1The action plan contained components such as outreach, identification, registration, counselling, support on getting treatment, follow-up, and social re-integration. All the stakeholders gave their inputs and agreed to work as planned. In the later stages, stakeholders such as Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA workers), school teachers and principals, senior citizens, and some local social workers also joined the campaign.

Roles and responsibilities were shared after the consultation meeting with stakeholders. The campaign required a space to run its activities and Tandel arranged a spacious hall on the second floor of the police station building. Some local leaders and traders provided Rs 20,000, which was needed to pay for printing costs, banners, and stationery. 2Since we took donations only in kind (for instance, stationery), the donors paid the amount directly to the vendors. Initially, we could not get much public response as people in the community were pessimistic about the campaign achieving its goals. So, we decided to go and talk to people with the help of local volunteers and encourage them to come for registration. This effort helped to break the distrust and dependents began to come to the police station for help.

We first made them fill out a registration form and tried to reinforce their motivation through counselling. We then sent them to government-aided Integrated Rehabilitation Centres for Addicts (IRCAs) for in-patient treatment. 3Integrated Rehabilitation Centres for Addicts are government-aided rehab centers run by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and funded by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. There are two functional IRCAs in Ahmedabad that offer three weeks of in-patient treatment and outpatient counselling services. Our team visited the IRCAs frequently and tried to keep the victim motivated during the treatment process. On completion of the treatment, we aided the recovering dependents by keeping them engaged in post-treatment activities such as weekly mindfulness meditation sessions and sharing sessions to prevent a relapse. We also carried out awareness generation activities amongst students and communities in the area.

Our drug and liquor laws criminalise people who are dependent on substances, punishing the victims, and creating a social stigma against them. This makes it difficult for the local police to enforce laws.

Some of our recovering dependents were invited to institutes such as the National Institute of Design to share their substance-free journeys. We observed No Tobacco Day and felicitated those who completed their treatment. As news of this initiative spread, people from other areas also contacted us and we provided them with technical guidance. At that time, 28 substance dependents living in Gomtipur had completed their treatment and remained sober for more than three months.

Then, one day, an unforeseeable problem interrupted our functioning. We were told to immediately vacate the office space for the traffic police, leaving us with no time to find an alternative place. We therefore decided to continue our activities remotely. However, we could not maintain the sense of purpose of our volunteers and supporters, for whom coming to the police station was a big motivation. We met the newly appointed Deputy Commissioner of Police (DCP) of Zone 5, requesting that an alternative space be provided in the police station for the initiative. The DCP expressed his inability to do so but offered his help to find space in a private hospital in the area.

Meanwhile, the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) protest began, and the focus of the police and community leaders shifted. Then came Covid-19, and the initiative came to an end. During the Covid-19 lockdown, all the recovering dependents, except two, relapsed, and we could not do anything but provide some of them with ration kits. The two remaining recovering dependents also relapsed in the aftermath of the post-Covid-19 economic distress.

Outcomes

The campaign initiated by the police station, engaging key stakeholders, and ensuring the participation of community members had a positive impact on the community. We have not measured the impact in terms of a change in perception and image, but the increased community participation in addressing a social issue, that too, without regard to the boundaries of religion, caste, class, gender, and political ideologies, suggested a powerful positive impact. The campaign made local citizens optimistic about coming together and collaborating to address any such issue.

Community leaders and workers began organising substance use awareness programmes at different locations. The campaigns established trust amongst marginalised communities of the area in the policing system, to the extent that they began sharing sweets and food with police personnel on family occasions. Many of them are still connected to Tandel and other policemen, and they voluntarily come out to assist the local police during religious processions and festivals. These were ordinary citizens who had never before interacted with the police because of fear and distrust.

Despite little success in preventing substance abuse, the initiative brought many stakeholders together and enhanced community participation in a collective effort to change the status quo. More importantly, the initiative established trust amongst community workers and ordinary citizens, which sowed the seeds of the collective response to Covid-19. During the pandemic, the Gomtipur police station was turned into a resource centre run by local community workers with the help of NGOs and police personnel.

During the Covid-19 relief work, many of us were infected with the virus and required hospitalisation. Tragically, one of the volunteers died, and another lost four family members. Following the second wave of Covid-19, numerous police officers, including the DCP and Inspector Tandel, were transferred. In the aftermath of the pandemic, many volunteers lost their jobs or sources of income and struggled with mental health issues. A new DCP requested that we restart our work at another police station, but he was transferred before we could operationalise the centre fully. The informal nature of the campaign was undermined by the frequent transfers of police officers and the waning motivation of volunteers.

Discussion

In a very populous country like India, nothing is small in terms of numbers. Even a police station-level effort may mean looking after more than 200,000 people, a city-sized population in many other parts of the world. In addition, Indian cities are full of people from diverse cultural backgrounds (Saha et al. 2021). Policies and interventions planned at the top may be less capable of factoring in that diversity. Castro and Alarcon (2002) suggest integrating “cultural variables” while addressing the issue of substance use rather than designing “culturally blind” interventions. We believe the existing substance use prevention and treatment policies designed at the centre, state, or even the district level are inadequate to respond to local socio-cultural realities.

For example, during the campaign, we interacted with some dependents who consumed legal substances such as pharmaceutical drugs and inhalants. They said they began consuming the substances as an option to liquor. 4When the Gujarat Prohibition Act was amended in 2017, bootlegging was affected for two to three months because of the stringent punishment in the new law. This was the time many alcohol dependents turned to sedative drugs and inhalants. We encountered an interesting case of a bavarchi (cook), whose eyes used to get inflamed when they lit firewood to cook at night, so much so that he could not sleep properly. A colleague suggested he have some liquor to help him sleep. He followed this advice and became a dependent alcohol user.

Misinformation about our initiative was also a major challenge. Some people (possibly local bootleggers and drug pushers) spread the rumour that the police wanted to make a list of alcohol and drug users so that they could be quickly rounded up if the police needed to show more arrests. However, through our regular outreach and engagements with local communities, we could effectively counter the misinformation.

Our drug and liquor laws criminalise people who are dependent on substances, punishing the victims, and creating a social stigma against them. This makes it difficult for the local police to enforce laws. We have often seen that when a dependent person is taken into custody, they have withdrawal symptoms such as nausea, excessive sweating, body tremors, paranoia, and seizures. The police then have to provide medicines or sometimes the substance the person is dependent on. Local police face these challenges on a daily basis but our policymakers seem to be ignorant about them. The UNODC’s call recommends treatment and rehabilitation for substance dependents, which the policing system should formally adopt.

A substance use prevention campaign integrating local socio-cultural factors and engaging local communities can be planned and executed at a police station level.

One of the significant limitations of the case presented here was that it was a personality-driven initiative. No institutional process was involved, and it was deprived of state resources. Moreover, it lacked accountability from all ends. This type of effort depends on a particular individual’s motivation and availability. Another big challenge in such local-level participatory interventions is establishing and maintaining the trust of communities, which can only be attempted through sustained efforts.

Ordinary citizens usually avoid participating in any social effort that entails risk or inconsistency. For instance, in Gomtipur, many people did not want to be a part of the campaign, fearing enmity from the drug mafia and bootleggers. Many people were apprehensive, saying, “Good police officers get transfers early, and we do not know whether the next officer will be interested in them.” These issues associated with personality-driven initiatives might not allow campaigns to survive long enough. There is a solid need to acknowledge the importance of Gomtipur-like efforts and institutionalise them to make them sustainable.

The issue of substance use affects all sections of society and is relatively less controversial to work on collectively. Hence, political hurdles or challenges are relatively few. Resource-wise also, it does not require big budgets. For example, existing public spaces, such as police stations, hospitals, or schools, can be utilised for carrying out activities, and information, education, and communication (IEC) material, which is developed by the health and police departments, can be used more efficiently. Since the economic burden of substance-induced health issues is very high, the limited cost involved in institutionalising such an initiative would be a good investment.

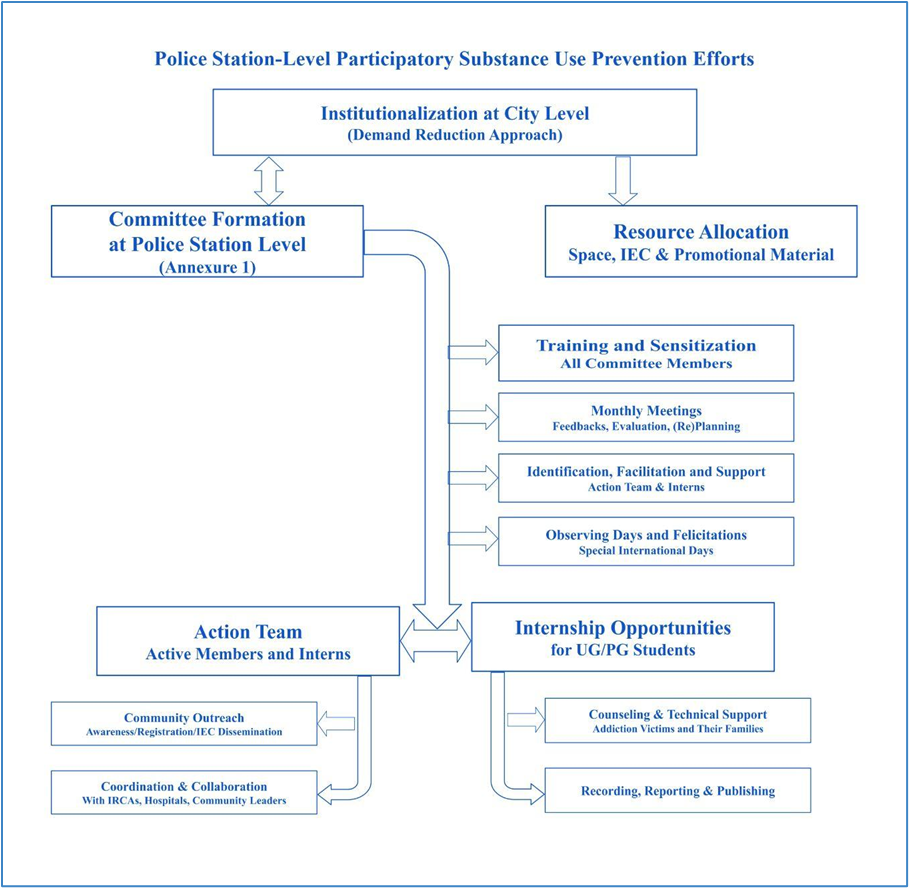

To conclude, a substance use prevention campaign integrating local socio-cultural factors and engaging local communities can be planned and executed at a police station level. The police departments in several states are actively trying to address the growing problem of substance demand amongst youth. It would be easier for grassroots workers and organisations to engage with the police and advocate for the institutionalisation of any campaign based on this model. These efforts to modernise the police are worth attempting at the local level by increasing community participation.

Proposed Model

Ajazuddin Shaikh is an anti-drugs activist who works as a research associate at Indian Institute of Managament Ahmedabad.