As Indian lawmakers set to reorganise family law in the years leading up to and following Independence in 1947, there was much ambiguity in their minds. Matters of marriage, divorce, inheritance, and guardianship were debated amongst the Indian leadership. Newspapers and journals joined in, and the contested perspectives carried into private conversations across the country. These heated discussions culminated in the Hindu Code Bill, steered through a stormy Parliament by the government of Jawaharlal Nehru, and passed as a set of acts between 1955 and 1956.

Women were at the centre of these discussions, yet they were peripheral to the decision-making. In 1952, after the first general elections in independent India, there were just 24 women amongst 499 Lok Sabha members and 15 in the 216-strong Rajya Sabha. If women’s voices were lost in the din of these male-dominated spaces of high politics, we need to look elsewhere to retrieve them. It is here that personal memoirs offer perspectives and possibilities.

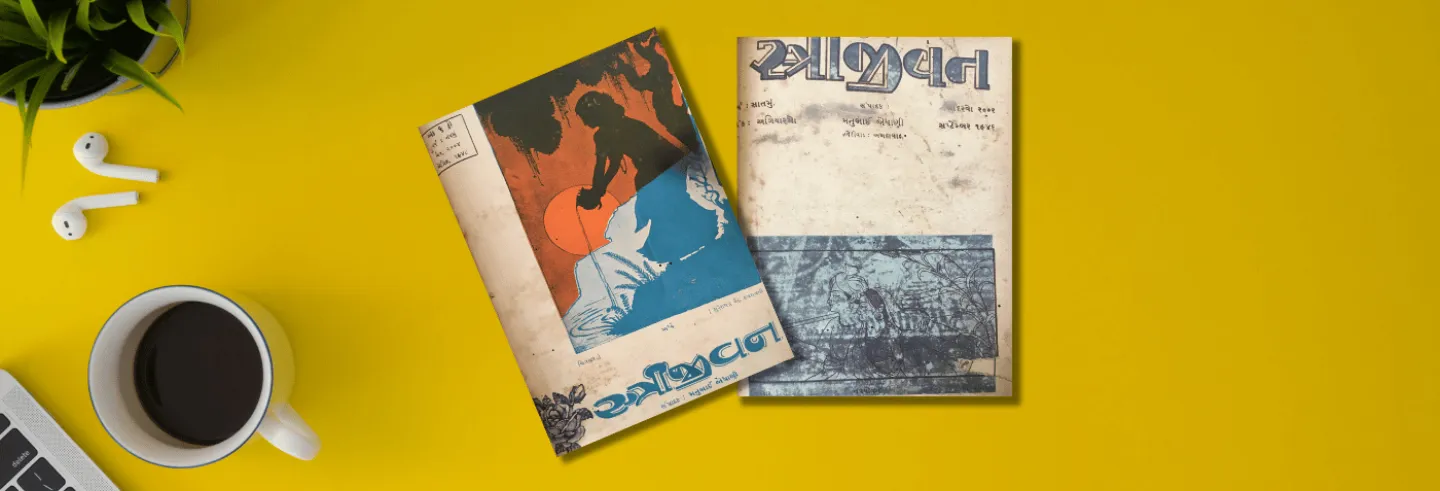

One such source, from Bombay state, was the realm of popular Gujarati journals aimed at women, which were engaged in fierce conversations about marriage, divorce, violence, and love. Through the fiction, non-fiction, and autobiographical essays in their pages, we get a sense of the discussions regarding political and social events thriving amongst women themselves.

These domestic manuals were widely circulated amongst the Gujarati community in what is today Maharashtra and Gujarat. Streebodh, the most prominent of them was founded in 1857 and ran until 1952. Established by a group of Parsi and Hindu social reformers, its subscription was Rs 3 per year before it was halved to Rs 1 and 8 annas in 1914. By 1950, the cost had risen to 6 rupees a year. With that price, and the expectation of literacy, the target readership was clearly the younger, middle class, upper caste women a generation which had access to schools and books.

In many of these writings, love appeared to mean the absence of infidelity by the husband, rather than affection, mutual respect, and companionship.

Much the same could be said about the other major journals, Strijivan and Guna Sundari. Each issue of these three journals included about 20 pages revolving around themes of marriage, intimacy, and infidelity. Women and men, married and unmarried, wrote essays, autobiographical and fictional pieces for the journals, but we know little about who the writers were, since no author’s note was made available.

These writings emphasised social and cultural norms rather than the role of institutions, laws, and policies. For most Indian women, access to legal institutions was beyond their reach, financially, culturally, and socially. The law could hold meaning and carry weight only when it was directly engaged with. These biting discussions were a far cry from nationalist voices (both within and outside Parliament that emphasised the sanctity of marriage and family to maintain national integrity.

The striking candour and honesty with which the women tell their own stories stand in contrast to men within their communities, as well as individuals or institutions that claimed to speak on their behalf. The women used ‘fiction’ and literature (often anonymously, and consequently, more openly) to make distinctly political statements, showing the significance of institutions and laws in their lives, and in the same moment, revealing their limits.

The suffering wife

‘Samajni Vantheli’ (The Bane of Society) published in Streebodh in 1950, was written by a Hindu woman who wanted to leave her husband because he “replaced” her with another woman. “After 25 years of journey as wife to my husband, in one instant, everything has been destroyed.” (All translations in this essay are mine.)

Even as she was careful never to directly refer to the proposed legislation on Hindu marriages and divorces, we can read the story as a subtle contribution to the emerging discussion. Her claim that Hindu women were capable of tremendous suffering and could tolerate a love-less marriage responded to criticisms that women would “misuse” the divorce law to carelessly leave marriages and cause a breakdown of the Indian family unit.

She wrote how she carried the burden of bringing her husband back on the “right path”. It was her role as his wife to “reform” his infidelity and wandering ways. It was only after every attempt to do so failed that she decided to go back to her parent’s home. She rejected society’s view of her as a “fallen woman,” and a burden on her elderly and poor parents.

She had few insults for her husband; reserving them for the woman her husband had cheated with, whom she called a veshya, a sex worker. She concluded by expressing her hope that her husband would recognise his mistake and remember the sacredness of their marriage vows.

The writer was careful not to overtly devalue marriage and conscious not to directly challenge its social standing – even as her story built a case for the opposite.

Throughout this autobiographical essay, the writer’s steadfast belief in the importance of marriage is apparent. She saw wives gaining respect from being notably distinct from the sex worker who was outside the family, degraded and immoral. Her own well-being hinged upon being married: the social stigma and ostracism that accompanied being separated was far worse than the compromised dignity it took to remain in the marriage. The emphasis placed on a woman’s marital status and the ways in which this status affected her health, finance, social status, and safety, offers a glimpse into what it meant to be an unattached Gujarati woman.

Striking in this essay is the writer’s understanding of love. In many of these writings, love appeared to mean the absence of infidelity by the husband, rather than affection, mutual respect, and companionship. The notion of physical or emotional love for a partner appears not to have been key expectations in a marriage. These discussions of marriage, property, and divorce were far removed from the legal system or official and national rhetoric of the time – instead, reflect the sobering reality of how women themselves navigated its many definitions in their quotidian lives.

Educated oppressors

“Shall I tell you the truth?” the author of ‘Mari Katha Sambhado’ (Listen to My Story) asked her readers. “Rather than cover up the ugly reality, shall I tell you the truth? He cared for nothing other than satisfying his bodily lust and having someone take care of his kitchen. Beyond that he had no special use for me.”

Like ‘Samajni Vantheli’, this personal memoir from 1947 in Strijivan too did not make any direct statement about the Hindu Code Bill. However, it covertly built the case for divorce on grounds of cruelty. The author describes her husband’s “shareerik bhookh” (bodily lust) in vivid detail and states that she would sooner be a sex worker than return to him.

Here too, the author hastened to tell the reader she believed in the sanctity of marriage, strategically maintained the readers’ sympathy, rather than being perceived as a ‘troublesome woman’. This conformity out of the way, though, she went on to describe her experience being mistreated by her husband: “I am a woman. I am a Hindu. It has been 7 years since I got married. My husband is BA LLB [. . .] I have not studied much. And not for much longer do I want to call him my husband.”

While she began by asserting her support for marriage, she ended her essay by smashing the very notion of lagn pavitrata (purity of marriage). She concluded by saying that she provides for herself and would only accept a life where she can live independently, with or without marriage.

The essay was a biting critique of a society that valued women only as wives and mothers. Rather matter-of-factly, the author declared that most women in India were unhappy.

The writer was careful not to overtly devalue marriage and conscious not to directly challenge its social standing – even as her story built a case for the opposite. She based her case for divorce on the sexual violence she experienced and covertly making the case for women to have the legal right to divorce. By repeatedly reminding the readers that her abusive husband was highly educated while she herself was far less so, she unsettled assumptions of education as the path to modernity and open mindedness.

It is likely that the writer believed that the injustice itself would not garner attention, and positioned herself well within the structures of patriarchy rather as a woman opposed to it. This construction of the good wife wronged by a cruel husband is a narrative that is self-aware of the social norms to be conformed to and the limits of the legal infrastructure, of the language of law, and its usefulness in her life.

Through these personal pieces that were neither confrontational nor overtly political, the writer – and the journal’s editors – were consciously building a case in support of the contentious divorce bill and for women’s rights in India.

No marriage is made in heaven

Draupadi ni Laj (Draupadi’s Honour), published in December 1946 in Strijivan, drew on the well-known theme from the Mahabharata as a commentary on the lack of respect given to women, both in India’s mythical past and in contemporary society.

The writer raged at Draupadi’s disrobing in the Kaurava court and made clear that the custom of laaj lootvani pratha (violating the woman’s honour) happened in the present as well. (The exception, she noted, was Shivaji, who treated even women from the enemy camp with respect.)

The writer detailed how Draupadi begged for help from those who were present, yet the crime continued. “In the full assembly, they tried to violate her,” the author wrote. “Draupadi begged the ‘good men’ and all present for justice. Those present fell silent. They were not willing to protect her […] All the five Pandavas sat cowardly in shame [...] If they had wanted, they could have cut the hands of the men who violated Draupadi and protected her. But that did not happen.” The story ends with Draupadi’s prayer to Lord Krishna for protection – miraculously her garment becomes endless and the lascivious intentions of her violators are defeated.

She concluded by saying that she was too embarrassed to say more about what women had to endure in contemporary society, but she hoped that women themselves would find their own solutions to unjust situations, like Draupadi was made to.

The writer discussed women’s employment and said that while women were successful and capable at work, they were not equipped to face the dangers of the world and could be bullied.

The writer’s ferocity at the injustice Draupadi experienced and her demand for a better treatment for women are compelling. The writer did not allow leniency to the gods in the Mahabharata, who too were complicit in the violence by their silence. Further, the emphasis on women supporting and helping themselves and each other was a move away from nationalist rhetoric of “Mother India,” where the woman was praised for suffering and sacrificing for her sons and the nation, or needed to be protected from the British, other men, and indeed, from the terrible burden of decision-making.

A married man not taking care of his wife was a popular theme across Gujarati domestic journals during these years. ‘Heejratu Strijivan’ (The ‘Heavenly’ Life of Women, meant ironically) in Strijivan of September 1946 brought up women’s experiences within married life, such as ideological incompatibility with the husband and difficulties in adjusting to life in a joint family with in-laws, and relatives.

“The roots of society are rotten,” she wrote. “If the root of the wounds itself are not taken care of, the smaller efforts above will not meet with much success.”

The writers of these stories challenged social norms without directly confronting them and spoke with honesty about issues such as marital disturbance and violence, even if they were unable to directly question or leave these difficult situations.

The essay was a biting critique of a society that valued women only as wives and mothers. Rather matter-of-factly, the author declared that most women in India were unhappy. The suffering of women was because the wife’s parents-in-law and husband wanted to control and claim ownership over her. She argued that when this status quo is threatened, the family often physically assaulted the woman; these reasons caused women to leave the house or commit suicide. The writer concluded by saying that it was important that women be protected from such men and their families, reiterating this point with a striking analogy: one arm of society had been given too much authority and this caused pain and suffering to the other arm.

The writer discussed women’s employment (though she did not specify any particular job) and said that while women were successful and capable at work, they were not equipped to face the dangers of the world and could be bullied. The writer did not detail what these dangers could be, but sexual violence is implied. “Girls and women should protect themselves against this kind of thuggery,” she wrote. “They must develop the strength to be prepared to fight against it.” She emphasised that it was essential for women to be mentally and physically capable of protecting themselves and tackling “unwanted situations.” She raised the issue of abuse within marriage and advocates for Gujarati society to reform, stating that since girls at a young age become wives and mothers, many suffered health complications during pregnancy, and some lost their lives.

The affecting tone and powerful voice make this a triumph of Gujarati writing during this period. The writer launched a systematic and persuasive attack on the most fundamental of social establishments – marriage and motherhood. Building logical arguments, the writer asserted that abusive husbands and imposing families were to blame for the ill fortune of women in India. The results of this were financial dependence, suffering, and loss of life due to medical complications in the case of frequent or early pregnancy.

An audacity that persisted

Engaging with women’s narratives, through their own voices, shows the depth of thought and diversity of opinions that they held that is difficult to identify in other sources. The writers of these stories challenged social norms without directly confronting them and spoke with honesty about issues such as marital disturbance and violence, even if they were unable to directly question or leave these difficult situations.

These writings raised two important discussions. First, the leadership and decision-makers in positions of power put forth opinions that were not representative of the middle-class Gujarati Hindu woman’s opinion. Second, the legal understanding of marriage and divorce remained distant from the notions of consent and coercion that were being negotiated by women within their marriages and families.

The writings acknowledged the importance of the law but recognised it limited access and usefulness in their lives. For many of these women, this remarkable self-awareness governed their conduct and familial negotiations. As they fiercely negotiated their familial and domestic lives, without relying on the definitions and accessibility of the legal system, they made powerful demands of it. The spirit and content of these writings in popular journals of mid 20th century Bombay is testament to the intellectual audacity of women who persevered within the spaces available to them.

Urvi Desai has a PhD in history and a Cundill Fellowship from McGill University, Montreal, Canada. She is co-founder of EkoGalaxy, a platform for climate education & engagement.