I’ll confess, I approached reviewing this book reluctantly. I am neither a Gandhi scholar, nor necessarily a Gandhian. And since architecture was not part of the general mythos surrounding Gandhi, I wondered what might my meeting with his places entail.

We are informed in the cover summary that the book is part of a larger documentation project of the built heritage in India associated with the life and work of Gandhi, with a mandate in part to set guidelines for the upkeep, maintenance and repairs of these buildings. The methods for documentation and the technical notes on the process indicate these were adopted in accordance with the conventions of the discipline of conservation. Although the larger project has involved sketches, photographs, condition surveys and material specifications, the book limits the scope to the inclusion of the architectural drawings for 11 core sites and 15 index sites. One can assume thus was so for the sake of brevity. The drawings are indeed meticulous, chronicling sites known and those less so, capturing scales and details of assembly with a sustained consistency. A curated selection of Gandhi’s notes situate each site in terms of its significance, and suggests an attempt at a realisation, in human terms, of the abstractions set forth in the drawings.

The documentation is bookended by three essays by the editors - Riyaz Tayyibji, Neelkanth Chhaya and Tridip Suhrud - that reflect on the meaning and anthropology of the built world of Gandhi. From these excellent meditations we get a sense that like his autobiography, Gandhi’s experiments with the built environment were material rather than abstract and driven, in his words, “by the dweller within”.

A curated selection of Gandhi's notes situate each site in terms of its significance, and suggests an attempt at a realisation, in human terms, of the abstractions set forth in the drawings.

The dweller within, as distinct from the “user” architectural parlance is familiar with. We learn that Gandhi experimented and transformed spaces through his inhabitation of them. The tool to record and register these experiments with was the body. Such deliberate inhabitation produces an authorship that is unusual, and utterly remarkable, to architecture. Authorship is traditionally ascribed to the one who conceives the forms and spatial compositions that are subsequently occupied. It is suggested that Gandhi’s is a form of authorship which most often goes unacknowledged when talking about buildings or architecture. This is an important contribution to both Gandhian and architectural scholarship made by the authors, and key source of value in the book.

Here Riyaz Tayyibji’s and Tridip Suhrud’s studies are particularly instructive:

“by changing the mode of ritualisation (of use and inhabitation), one could easily turn a house into a shrine, or for that matter the cell of a prison into the cella, or inner chamber, of a temple. This is precisely what Gandhi did when he was imprisoned in Yerawada Central Jail in Pune: he recognised the prison cell and the corridor in archetypal terms, and referred to the prison as Yerawada mandir, or temple. It was the manner in which he inhabited the prison that denied his imprisonment”.

There is a critical intimacy alluded to here with regard to authorship. A critique of both, the enlightenment project as a project of distancing (in the name of objectivity), and of archaic social norms which prevent individuation (or more precisely, self-awareness) - both consequently eliminate the possibility of that “inner dialogue”. The ability to identify differentiations in form and their social affordances in a typological sense may be at the centre of Gandhi’s ability to reflectively transform through inhabitation. The form would not have to be distinctive, but has significance.

We learn that Gandhi experimented and transformed spaces through his inhabitation of them. The tool to record and register these experiments with was the body.

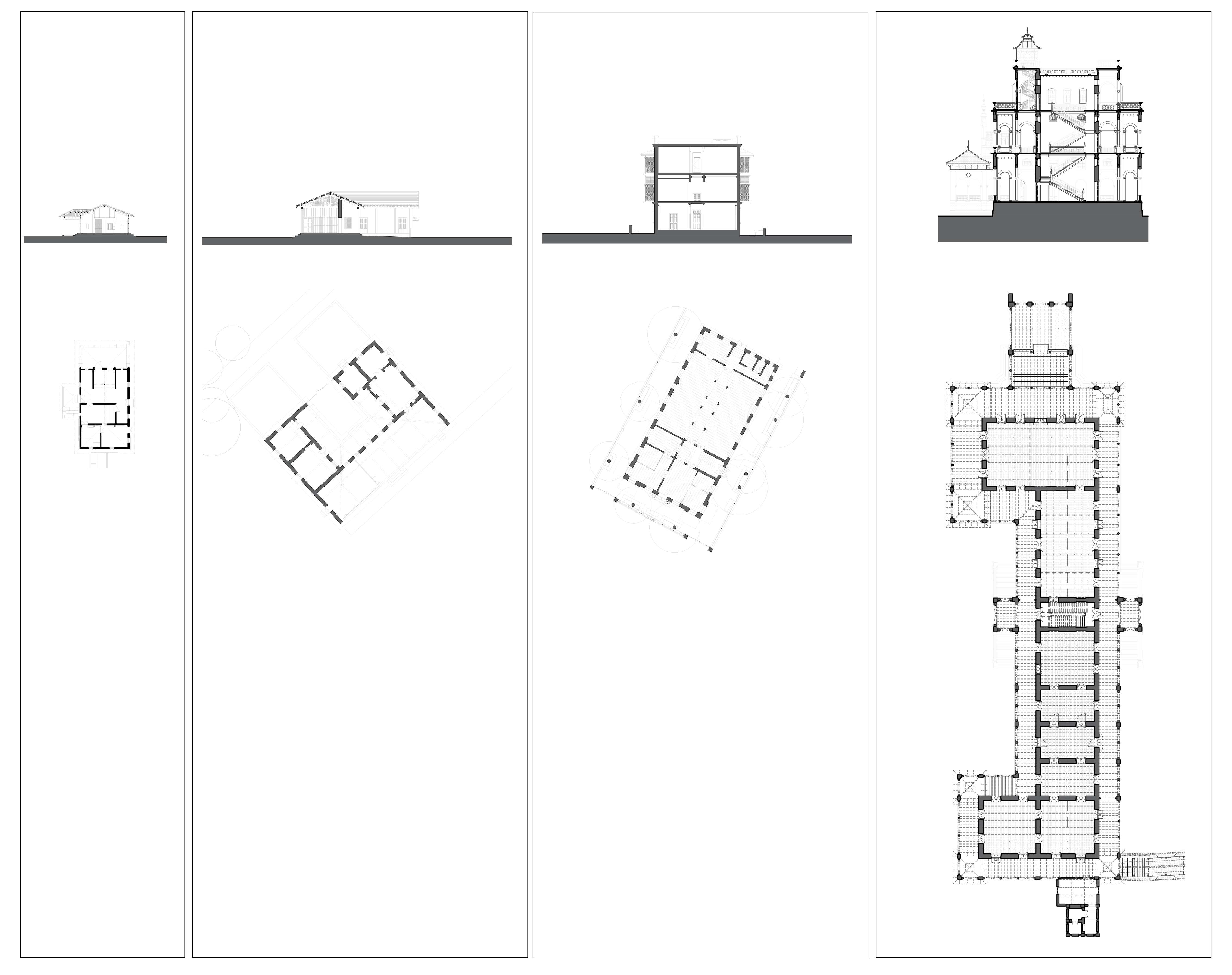

It raises the question of whether most of the places chronicled have gained their significance because of their association with Gandhi, rather than as remarkable works of architecture in themselves. Formally, we see the places documented fall into one of two types. First, the buildings that are part of a larger urban fabric, built up incrementally around a central courtyard, the result of the steady accretion of generations. These were also buildings associated with Gandhi’s early and formative years, such as Gandhi’s place of birth in Porbandar, and the house he grew up in Rajkot. The second, the archetypal bungalow in the 19th century which consisted of a symmetrical internal layout, with a veranda all around, situated in a large, landscaped compound; a counter concept to the more or less socially geared, community-oriented, collective lifestyle that was manifest in the buildings Gandhi grew up in. Many of these were generously made available by wealthy patrons, such as the Kochrab compound, the Bajajwadi and the Aga Khan Palace.

The two projects that are an exception here are the two ashrams in Ahmedabad and Wardha, where Gandhi’s role as an author, architecturally, is more familiar to us. But here too, the editors point us to Gandhi’s praxis of “opening up” insularities to set up dialogue and a subsequent inquiry into the shared ground between two seemingly opposed categories - be it material, spatial or phenomenological. The gradual dissolution of a “closed room” for cleansing—the bathroom at the Bapu Kutir in Wardha is one instance that comes to mind. Tayyibji writes that the opening up of the private space of the body as an expression of a new, modern relationship between body and dwelling is one of the most important and consistent themes across Gandhi’s buildings.

When Gandhi speaks of his home in Porbandar being “a vision of after-thoughts”, is he expressing an ambivalence towards the built structure, suggesting that it is in fact the inhabitation and the relationships that inhabitation engenders, that renders a space its meaning? And if conservation’s imperative is to be a custodian of these meanings, what should we be documenting, and indeed how? Do the drawings, following the norms of the discipline, represent that meaning adequately?

There is a tension throughout the book between the specificity demanded by Gandhi’s critical inhabitations, and the standardisation in documentation demanded by disciplinary [best] practices. The key relationship between Gandhi’s practice and the manner of inhabitation of spaces that resulted in the built environments he authored, or had a hand in their authorship, is missing; flattened, as it were, into a singular symbolic narrative in his name. Or rather, it is left to be constructed in the reader’s mind from the drawings (infrastructure) and the text (inhabitation). To make legible a consistency of representation at the cost of making subjective the rigorous deliberation of Gandhi’s practice is a curious choice, raising questions about the nature of the current discipline of conservation, authorship and custodianship.

Gandhi’s engagement with materials and how they are processed was not a casual one. This is made explicit in all three essays. His first experiments were with food, and later, he taught himself carpentry and to work with leather and fabric. He was particularly interested in materiality, the relationship between material, its processing and production with labour and the human body. Building was merely an extension to this practice. Should not, then, its custodianship acknowledge and answer to this practice?

For example, one wonders the implication of an abstract precision borrowed from the architecture of dressed stone (Kochrab, or the Aga khan Palace) imposed on a building with mud plaster (Bapu Kutir), with fundamentally different material tolerances given the many hands and repeated acts of plastering required to maintain a building using mud. What should be the mode of recording and representation that support Gandhi’s relationship with labour and material, as suggested in the essays? In the absence of questioning disciplinary frameworks of documentation, one ends up distancing the various stakeholders who are party to the reconstruction. Is the documentation for them? It seems one of the consequences of heritage conservation with its apparatuses of listings and inscriptions is that it reframes a “culture of maintenance” from a performance of quotidian acts, to one that requires increasing professional expertise. Purely professional frameworks, divorced of empathy and the anticipation of the labour of conservation, distance us from our built environments rather than enabling re-inhabitations.

There is a tension throughout the book between the specificity demanded by Gandhi's critical inhabitations, and the standardisation in documentation demanded by disciplinary [best] practices.

Might drawings be made to anticipate the labour of conservation and participation rather than retreating into known frameworks of how the discipline operates with expertise and exclusions. Drawings not merely as representations of prior inhabitations, but those that begin to acknowledge the inhabitation of the practice of care. Conservation after all, at its core, is a form of care, of custodianship of that which we inherit. What we choose to document expresses what we consider of value. Drawings are a language, with which we meet the world. In this case the world of Gandhi’s practice, again. They are simultaneously acts of reflection, and re-membering. Given Gandhi’s unique authorship in architecture we have the opportunity of our own disciplinary “opening up”, of reconfiguring what we record, the manner of how we record and indeed what can be recorded. Consequently, the transformation of the act of documenting and its impact on each representation provides an opportunity, or fulcrum, through which to explore the discipline of conservation, its cultural perceptions, valuations and understandings of the nature of the places represented.

It is perhaps here that Neelkanth Chhaya’s essay on the condition of the in-between as the driving force becomes most poignant. With the nature of documentation of Gandhi’s Places, we find ourselves in another liminality, which Chhaya observes is “a condition of being in search of, rather than some point of rest”. What we find ourselves here is a disciplinary liminality, caught between the inhabitation that has occurred, and the inhabitation anticipated. An inhabitation, our inhabitation and its search for an ethos of care.

Shubhra Raje’s practice involves designing buildings and teaching architecture. With graduate and postgraduate degrees in architecture from CEPTl and Cornell Universities, she founded shubhra raje_built environments, an architecture and design studio that concerns itself with relevant design, architectural economy and spatial ecology. (www.shubhraraje.com)