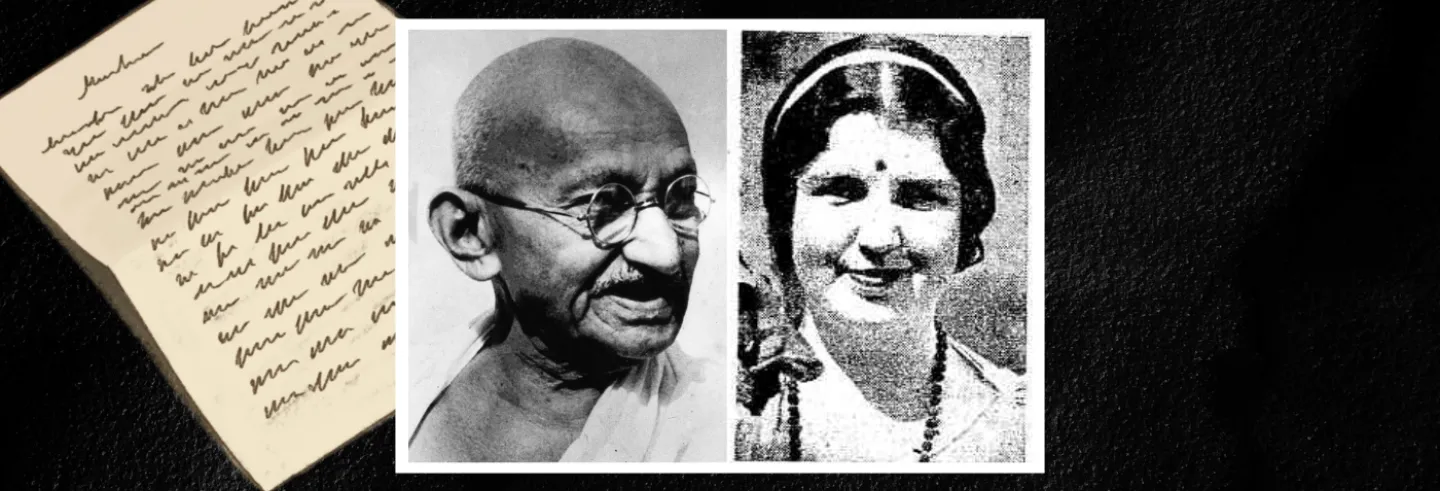

Addressing the inmates of the Satyagraha Ashram on 13 May 1926 on the sixteenth verse of the fourth chapter of the Bhagavad Gita, as part of his series of discourses on the subject, M.K. Gandhi sought to bridge the divide between the private and the public, and that between the hermitage, the home, and the polis in the personality of the karma yogi, or ideal agent for public service.

The evening before, he had happened to rebuke certain boys of the ashram, who, in turn, had pointed out that the tone of his reprimand indicated latent anger. Gandhi publicly accepted this the next morning, attributing his anger to his inability to rein in his passions. However, while acknowledging the difficulty of freeing oneself from passions, he spoke of the qualities of vigilance and tenderness required in an aspirant for liberation. These qualities bear meaningfully on why, seven years later, he offered succour to Nilla Cram Cook through her many upheavals and tribulations.

“If I run away from a task in despair, if I get upset or raise my voice because … does not listen to me, I weave the bonds of karma round me. Having undertaken a duty, having agreed to look after some children entrusted to me and sharing the responsibility of bringing them up, how can I run away from the task? If I retire to the heights of the Himalayas and live there in peace, I would be indulging my body in idle comfort and weave round myself the bonds of karma. I must, therefore, remain in the midst of these responsibilities, and win moksha through them. If I become free from anger and shake off ignorance, if I become more vigilant and alert, I would be doing no karma even when occupied in some karma.”

For his ideological interlocutors, this view resulted in his oft-exasperating claims of his embodying alike a Muslim or Christian, a suffering Harijan, a harassed, even menstruating, woman, and obviously, also a true Hindu.

Filial responsibility or empathy evidently played a crucial role in Gandhi’s concept of detached action. In a discourse on 23 March 1926, he linked detached action with an actor of “resolute intellect” who is able to “work without looking for immediate results” in the realm of “politics or social reform”. Successful political action, therefore, was tied by him to the cultivation of an interiority, including quotidian homemaking, humility, and non-violence. An absence of desire led to niskama karma, and, by extension, to the relinquishment of identification with an othered selfhood, therefore reconstituting the political actor for successful political praxis.

For his ideological interlocutors, this view resulted in his oft-exasperating claims of his embodying alike a Muslim or Christian, a suffering Harijan, a harassed, even menstruating, woman, and obviously, also a true Hindu. On a different plane, his view of selfless action partly explains his forbearance with the occasionally wildly eccentric behaviour, or worse, of a follower. In this case, it was the behaviour of Nilla Cram Cook, which, while driving Sardar Vallabhai Patel to resigned indifference, was perfectly intelligible to social worker Amritlal Thakkar, also known as Thakkar Bapa.

Gandhian scholarship needs no introduction to E.S. Reddy. A career diplomat in the United Nations, he remains unmatched among his peers in his life’s devotion to the elimination of apartheid, and unrivalled in his familiarity with archival sources for chronicling Gandhi’s life and movements in South Africa, along with those of his main associates. This epistolary volume is his final contribution to academia, fittingly completed after his demise by another scholar of comparable erudition and dedication, Tridip Suhrud.

The correspondence between Gandhi and Cook, compiled and edited meticulously, serves the immensely valuable purpose of historicising a crucial part of the world of Gandhi. His relationship with Cook illustrates the natural affinity that women usually felt towards him, and his own conception of his generally filial approach towards participants of his movements, particularly the inmates of his ashrams.

It also illustrates his rare understanding of the enchantment of regarding service to Harijans as an exotic experience other than an expiatory one, which made it necessary for one to be very vigilant against exploiting the vulnerabilities of the deprived and disinherited. Most of all, it illustrates the sacrality that Gandhi perceived in the Harijan cause, any other word being wholly inadequate to describe its place in his moral universe. Here, it also explains the real reasons behind his decision to embark on a 21-day fast of atonement in May 1933.

Beginning in November 1932, within the space of hardly a year, Cook wrote what can only be described as a flurry of letters to Gandhi, receiving usually prompt, though not always the expected, responses from him.

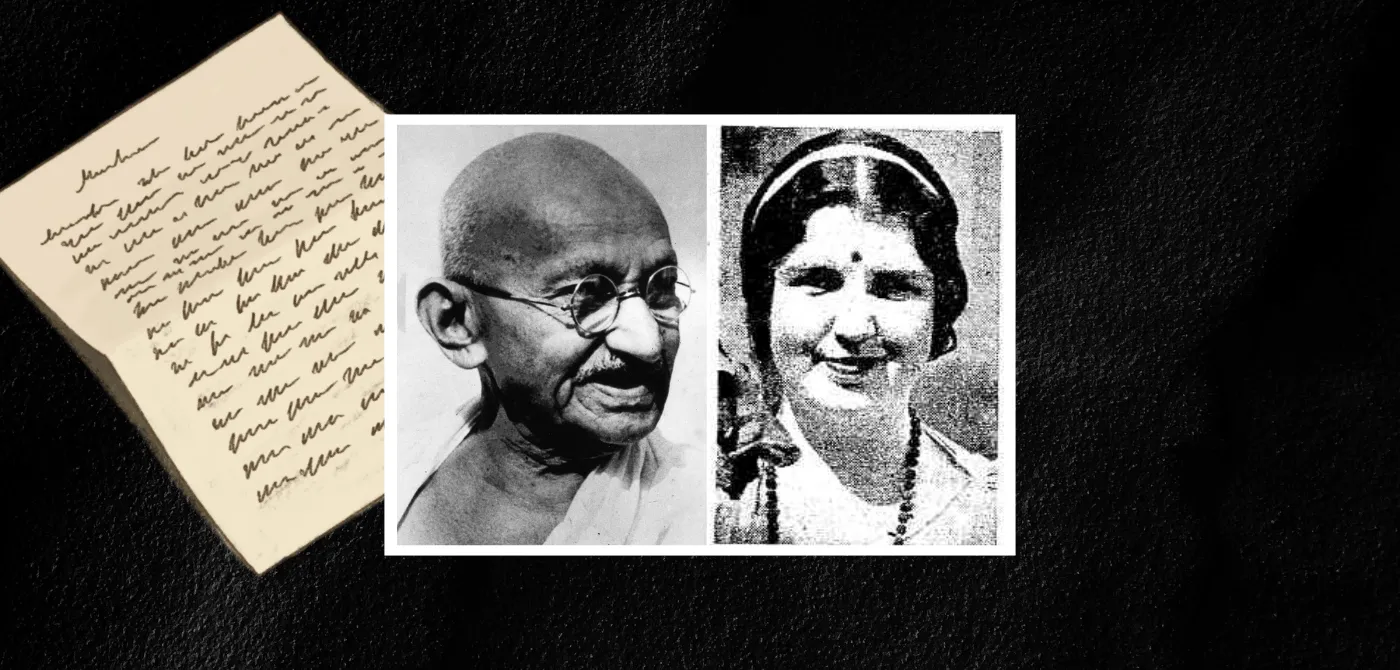

The account of Cook’s life in India, provided in the introduction to the correspondence—attended to in greater detail in Thomas Weber’s study of Gandhi’s women followers—makes for painful reading. Cook, or Nila Nagini Devi as she was also known, swirled in the currents of her mercurial temperament, her lack of inhibitions and striking beauty drawing admirers to her. They were willing to provide her with logistical support for indulging her numerous itinerant whims, including introducing her to Indian royalty. Individuals as varied as ministers of Indian princes, venerable pedants, staid journalists such as Durga Das, and countless youths from all sorts of backgrounds were participants in her enterprises.

Born to a broken marriage between bohemian American parents, raised for some years in Greece, married and divorced at a very young age, and generally disillusioned with life in the West, the talented and versatile Cook arrived in Kashmir in 1931 with her young child. Bereft quite soon of her inheritance, scarred by exploitative physical relationships, and with spiritual bliss still elusive, she appeared to find solace in Harijan service, having been introduced to it by Thakkar, the secretary of the Harijan Sevak Sangh. Her contact with Gandhi and his anti-untouchability campaign of 1932 soon followed.

Beginning in November 1932, within the space of hardly a year, Cook wrote what can only be described as a flurry of letters to Gandhi, receiving usually prompt, though not always the expected, responses from him. Her letters, graduating from the initial address of “Revered Mahatmaji” and signed as “ever yours in service and devotion, Nila Nagini” to the final phase with “Beloved Bapu” and “With all our love, Nila”, contain her thoughts and plans for Harijan service, and many other things.

They express her weakness before a desire that blurs both social norms and ethical principles; they complain about the hardships of slum housing or the defects of the Satyagraha Ashram; and they agonise about her physical ailments and those of her son, and even speak of her menstrual problems. Above all, the letters plead for guidance and nearness. As the volume reveals, Gandhi’s responses—even when he seems on the verge of giving up on her for her immorality and weakness before desire—never waver in their caring tone. He advises her on her diet and spiritual upliftment, on a possible pregnancy after an indiscreet encounter with a youth volunteer in Harijan service, and is solicitous about the welfare of her son. Gandhi remains, to all intents and purposes, a combination of a father and a mother to her.

After a troubled stint in the Harijan cause and increasing restlessness in Satyagraha Ashram, Cook left Ahmedabad in October 1933, without informing Gandhi, never to return. Only a few letters were exchanged between them after this.

Yet, another significant learning emerged from this relationship. Cook’s brief but disappointing relationship with Rudramani, a Harijan youth, jolted Gandhi. Although in this case he was critical of Rudramani’s conduct, on the general plane, it rudely brought home to him the possibility of helpless men and women being treated as emotional and physical prey by volunteers turned predators, all in the guise of service. He was very aware that in informal interactions between young and healthy men and women, erotic desire could be at the root of attraction though it could be camouflaged as a spiritual yearning for a higher cause.

In a warning in the 'Harijan' on 6 May 1933, he wrote he knew of the “young men who fell under N.’s spell”. He appealed to the youth to learn the right lessons from Cook’s story.

It will not be out of place to mention at this point an obiter, from Rabindranath Tagore’s fictional critique of revolutionary terrorism, Char Adhyaya (“Four Chapters”; 1934). Here, the heroine, Ela, plays her part in a terrorist enterprise by performing an act of unconsciously semi-erotic invitation, inflaming young recruits by marking the foreheads with “drop[s] of blood-red sandal paste” and initiating them to the group. The leader regards her as subconsciously performing the role of a kamini (desirable woman).

Coming back to Gandhi, when the camouflage wore off, predatory impulses could wreak havoc and provide a fertile ground for exploitation, including sexual crimes. In a warning in the Harijan on 6 May 1933, he wrote he knew of the “young men who fell under N.’s spell”. He appealed to the youth involved in Harijan service to learn the right lessons from Cook’s story.

But the matter did not rest there. In all probability, it was the main reason Gandhi decided to embark on a 21-day fast on 8 May 1933 to highlight the plight of India’s untouchables, which has been described by many as his noblest fast. Scholars have speculated that the fast was atonement for Gandhi having wronged B.R. Ambedkar, but that is unlikely given that his essential belief in the structure of Hinduism was unshakeable.

On 30 April 1933, Gandhi issued a statement on the fast, which was prominently carried in the Bombay Chronicle the next morning. It stated that the fast was directed against himself, to atone for his own omissions as well as those of his associates. “Let there be no misunderstanding about the impending fast. I have no desire to die. I want to live for the cause, though I hope I am equally prepared to die for it. But I need for me and my fellow-workers greater purity, greater application and dedication. I want more workers of unassailable purity. Shocking cases of impurity have come under my notice. I would like my fast to be an urgent appeal to such people to leave the cause alone.”

The volume under review has been carefully compiled and has a sensitive and informative introduction that makes it both pleasurable and knowledgeable reading. It will retain its archival and exegetical value for years to come.

Gangeya Mukherji is an independent scholar with an interest in the history of ideas in 19th and 20th century India. He is the author of Gandhi and Tagore: Politics, Truth and Conscience (Routledge, 2016), and An Alternative Idea of India: Tagore and Vivekananda (Routledge, 2011).