On 22 June 2018, the priests of Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple 1 Ranganathaswamy is another name of Lord Vishnu, one among the trinity of popular gods of the Hindu religion. Sri is a prefix used to signify respect. – a highly revered temple in Srirangam, Tamil Nadu – honoured the then working president of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) MK Stalin. He was in the city to attend a party meeting.

The DMK and its ideological predecessors are regarded as vehement proponents of rationalism, and are often criticised by Hindu groups for doing so. The honours were done at the temple’s entrance, which among other things involved smearing turmeric paste on Stalin's forehead. After the honours, he was seen to have wiped off the paste. The acceptance of honours and the subsequent removal of the turmeric paste attracted criticism that he showed dishonesty towards rationalism on one hand, and disrespect to the sentiments of Hindus on the other. In response, the then Union Minister in the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government, Pon. Radhakrishnan, who was also a Member of Parliament fromTamil Nadu, remarked: “If Stalin is an atheist as he claims, why should he accept the honour? Who gave Stalin permission to commit an act of profanity and insult God?”

[W]e wish to recall an instance from the past in Malaysia where the Self-Respect Movement ... simultaneously participated in a temple entry movement and questioned caste hegemony and elaborate temple rituals...

This is one among many other criticisms put forward by BJP leaders challenging the nature of politics practiced by the DMK. In response, DMK leaders cited instances from the past where M. Karunanidhi, the party’s late president and former Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu (Stalin’s father), partook in similar ceremonies. One might also argue that such an act could be a result of political compulsions. On the other hand, unpacking the event could help explore the dimension of coexistence and foster it consciously. To do so, we wish to recall an instance from the past in Malaysia where the Self-Respect Movement (SRM), often referred to as the ideological predecessor of the DMK, simultaneously participated in a temple entry movement and at the same time questioned caste hegemony and elaborate temple rituals, to the extent of disavowing religion. We also look at these instances through the prism of agonism and argue the need for a space, which involves conflict too as against just consensus-building in societies marked by diversity.

Tale of the Thaipusam Procession in Malaysia

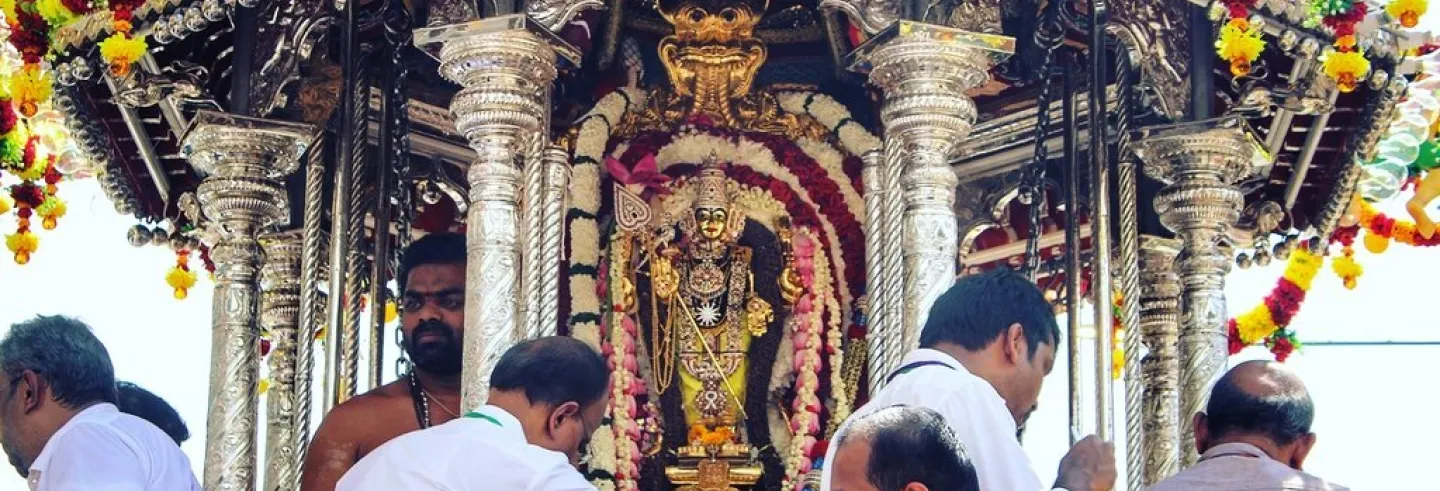

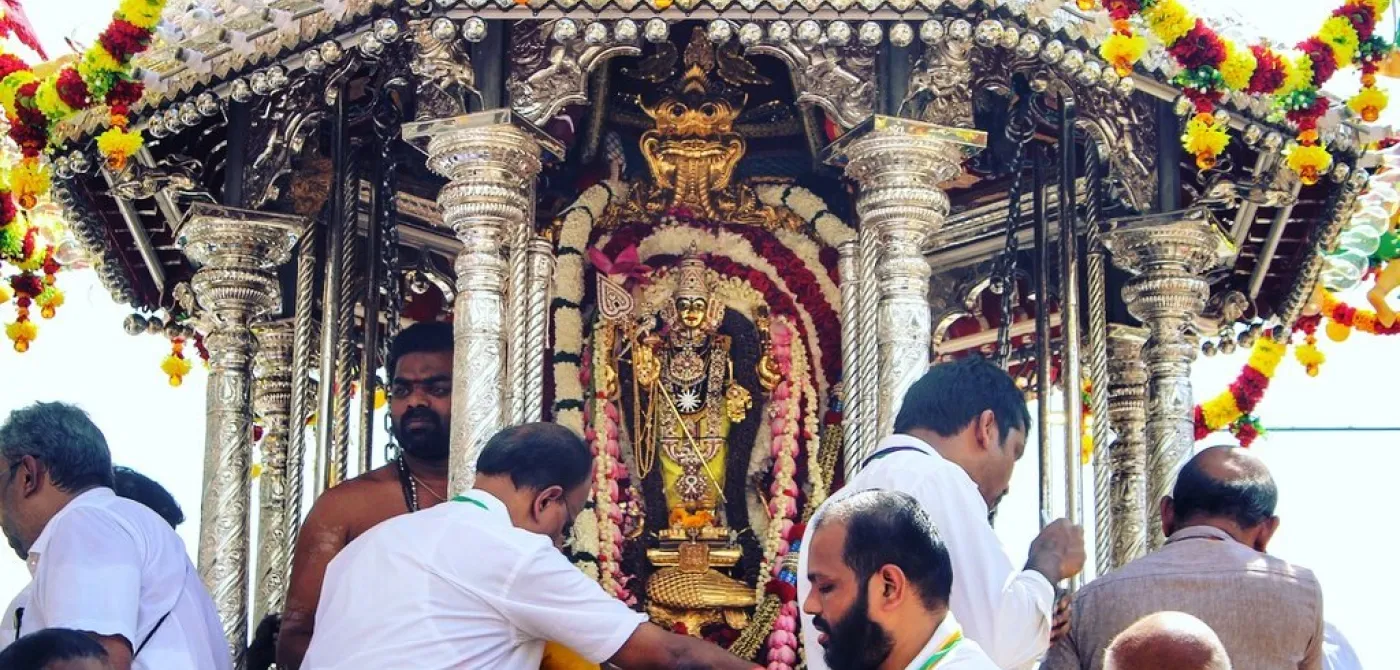

Following the British occupation, peninsular Malaysia saw an influx of south Indians in the 19th century, especially Tamils from across the Bay of Bengal. Thaipusam is an annual festival celebrated in the month of January / February. The chief deity involved is Murugan 2 Murugan is believed to be the younger son of Lord Shiva. He is also known by names like Subramania and Dhandayuthapani. who is regarded as a Tamil God (Venkataraman KR. 2007: 309). The festival, among other things, is marked by a procession of the deity through the streets around the temple.

A controversy around the Thaipusam procession in Penang emerged when the dominant Nattukottai Chettiar community 3 It is a merchant banking community from South India. See Rudner (1994) Chettiars. Berkeley: University of California Press attempted to appropriate the tradition associated with the worship of Murugan during Thaipusam.

The temple at the centre of the Thaipusam procession was the Arulmigu Bala Dhandayuthapani 4 Arulmigu loosely translates to ‘grace-rich’ and Bala signifies the premarital age of the consecrated deity Dhandayuthapani loosely translates to spear-wielder. Temple – also known as the Penang Hill Murugan Temple. It was built in 1855 (Collins, E., & Ramanathan, K. 2014: 83-105) on 11acres of land granted by the British authorities. The Thaipusam procession would start from the foothill of Penang Hill at the Maha Mariamman 5 Mariamman is a manifestation of Durga and the Maha is a prefix used to signify might. Temple on Queen Street in George Town, which had been consecrated in 1833 (Jenkins, G. 2008: 39). The Maha Mariamman Temple was built by a consortium of different caste groups on land granted by British authorities in 1801.

The seeds for altering established practice in the worship of Murugan during Thaipusam were sown in 1875. The then money-lending community and erstwhile salt traders from Karaikudi — the Nattukottai Chettiars — built a hall at the foothill of Penang Hill exclusively for their community. Subsequently, it was expanded to become what was called the Waterfall Road Subramania Temple. It was followed by procuring a silver chariot from India to carry an image of Murugan on the eve of the annual Thaipusam procession, which was called “Chetti Pusam”. Thus, an exclusive caste ritual came into the picture along side the Thaipusam, a festival that was otherwise celebrated by multiple communities.

Owing to its extravagance and popularity, the Chetti Pusam procession led to the alteration of the usual routes of both processions. The processions then began at a shop-house owned by a person from the Chettiar community and ended in the Waterfall Road Subramania Temple that had been built by the Chettiar community. The dominance asserted by Nattukottai Chettiars as patrons of the Thaipusam procession derived from their affluence and their status in the Hindu community of Penang. This led to conflicts over the control of the Queen Street Maha Mariamman temple in order to restore the old procession route.

[I]n 1933, the Queen Street Maha Mariamman Temple became the first in Malaysia to open its doors to the perceived “untouchables”, and “lower castes” like the Nadars.

These conflicts led to court cases, which were resolved temporarily in 1904 when the colonial office appointed a British official as a trustee of the Maha Mariamman temple. Furthermore, in 1906, 'The Hindu and Muslim Endowments Ordinance' was passed, establishing British authority over of all temples and mosques in the Straits Settlement that had been built on the land granted by the colonial office.

Then, in order to restore the usual route of the Thaipusam procession, the Queen Street Maha Mariamman temple acquired a chariot. However, it was not successful in thwarting the dominance exerted by the Nattukottai Chettiar community. Meanwhile, in 1933, the Queen Street Maha Mariamman Temple became the first in Malaysia to open its doors to the perceived “untouchables”, and “lower castes” like the Nadars.

The Role of Self-Respecters

One can trace this resistance to the caste-hierarchy and exclusionary practices of orthodox Hindus to the ‘temple entry movement’ inspired by the political developments in India at the time. The historic opening of the Maha Mariamman temple to all was brought about by the campaign spearheaded by the Pan Malayan Dravidian Association (PMDA). The popular rhetoric around the temple entry movement in Malaya dates back to 1929, when Periyar EV Ramasamy, who is regarded as one of the central ideologues of the Dravidian movement, visited Malaya. (Solomon, J. 2012: 257-281) The members and supporters of the PMDA were drawn from lower castes and Dalits – many of whom were 'Self-Respecters'.

At the same time, the dockworkers in Penang formed the Hindu Mahajana Sangam (HMS), a social welfare association that organised protests against the exclusion of Dalit workers from entering the temple. The steady mobilisation and protests from both the PMDA and HMS simultaneously, not necessarily together, led to the latter gaining control of the management committee that was responsible for the conduct of affairs in both theMaha Mariamman temple and the Penang Hill Murugan temple. The developments culminated in the restoration of the procession route for Thaipusam, while the Chetti Pusam route was left untouched.

Moving Beyond Temple Entry

While fighting for temple entry in Malaysia, the Self-Respecters formed the Tamil Reform Association (TRA) in Singapore, an organisation that brought together middle-class Tamils who were open to reforms. (Solomon 2014: 133-151). Interestingly, the TRA was at the forefront of calling for radical socio-religious reforms amongst Malayan Indians. It was formed in 1929, initially as a caste society calling itself the Agampadiyar Sangam 6 Agampadiyar or Agamudayar is a backward class predominantly residing in Tamil Nadu. See: http://www.tn.gov.in/rti/proactive/bcmbc/handbook-bcmbc.pdf. and was renamed as TRA in 1932. (Raman, B. 2018: 138). The TRA went against rituals that involved piercing body parts during the Thaipusam and argued that there were no religious sanctions for such forms of worship in the tradition of Murugan worship. Their ideas were given effective expression with a spate of journalistic activity, beginning from the late 1920s.

Munnetram, (“Progress” or “Upliftment”), a magazine, started in 1929, Seerthirutham (“Reform”) in 1931 and Tamil Murasu (“Tamil Drum”) in 1935, were based in Singapore. All the magazines carried extensive reports of the Dravidian movement in south India. The issues covered included the evils of caste, the need for temperance, improved education and health, the eradication of rituals such as fire-walking stemming from Hindu practices, support for properly registered, non-religious, monogamous Hindu marriages, and emancipation of women. The wide circulation of Tamil Murasu serves as a strong testament to the popularity that these ideas garnered. Tamil Murasu went on to become the main rival of Tamil Nesan (“Tamil Friend”), a magazine that was considered to be supporting the status quo (Sinha 2011: 212).

Fostering the Spirit of Coexistence

On the face of it, these stories and developments seem rife with contradictions. However, an analysis through the lens of agonism — a theory that has been extensively used to understand democratic societies marked by plurality — provides a perspective on the intricacies involved in fostering harmony in a diverse society.

Chantal Mouffe, a proponent of agonism, argues that while consensus-building (propounded by deliberative democracy theorists) is one way of settling conflicts or differences, many a time it is marked by an element of compromise, often in the nature of limiting one party. Moreover, consensus-building does not provide space for discussing conflicts, something which a democratic society should provide. One can argue that the absence of such a space for discussing conflicts is inimical to the very idea of freedom.

[T]he fight is not primarily against a person or a community but a given state of mind.

In this context, an agonistic framework is one that provides space for debating differences and conflicts. Such a space nurtures discussions and debates which, in turn, lead to an organic evolution of a society where the constituent elements are not a given but are defined and redefined at times in a discursive manner.

For instance, in response to the usual criticism about the Dravidian movement being anti-Brahmin, a prominent leader of the DMK, A Raja, argued that the word Brahmin in the Tamil context did not refer to a person per se but to a bunch of oppressive traits and to any person or a group carrying those traits who needed to be fought. In other words, the fight is not primarily against a person or a community but a given state of mind. In the Penang story, the Nattukottai Chettiars were the oppressors who were questioned by the Self-Respecters who in turn did not differ with an apparent religious outfit like the HMS on the issue of procession route.

Conclusions

One can argue that the Dravidian movement did not forcefully seek to arrive at consensuses in matters concerning particular interests of individuals. That said, consensus-building also has its usefulness in terms of maintaining peace and order as against a chaotic atmosphere breeding disparate ideas.

If one were to look for points of consensus within the Dravidian movement they can be found in discussions concerning the framework of the movement on the whole. The framework within which the movement operated is broad and the ideas that regulated the contours included social justice and democratisation of public spaces. Moreover, one can argue that the consensuses built were discursive, constantly seeking to include and accommodate differences, and foster an environment of coexistence. Beyond this framework, public and private spaces were characterised by extensive debates and discussions where one could raise his / her concern and discuss it elaborately without the fear of being subjected to a sense of conflict against the dominant or majoritarian culture. When questioned about similar contradictions CN Annadurai, Tamil Nadu’s first Chief Minister and the DMK’s founder, observed:

I wrote the script for Swargavasal, a film which proved quite popular in Tamilnad. In this, I discussed the theme of atheism and theism. I have drawn the conclusion, which I felt was reasonable that reliance on too many gods and rituals was not necessary for faith in God. I said true faith in God is to have faith in fellow human beings... Of course, I am a rationalist who wants to end unreason and blind faith in the people. But genuine belief and true faith in God should be there amongst the people so that it helps them to become more and more aware and conscious of their duties and responsibilities to their fellow human beings (Ramanujam, K S. 1967: 250-251).

By way of conclusion, one could say that the criticisms put forward by people like Pon. Radhakrishnan that are stuck in binaries come in the way of imagining or discussing diverse societies. Furthermore, while the DMK movement may have its own issues, its sustenance over half a century has hinged on a spirit of accommodating differences, thereby serving as an example from which one can pick up a lesson or two.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kalaiyarasan A. and Karthick R.M. for their feedback.