Starting 1898, Bangalore experienced a plague epidemic that killed nearly a tenth of its inhabitants. The Indian population that lived in densely populated settlements bore the brunt of the epidemic, suffering the most casualties (Caldwell 1899). In the aftermath, the British colonial administration and the princely state of Mysore undertook sweeping urban reforms that changed the spatial composition of the city.

The implications of these changes for housing and land-use patterns of the city remain till today. Through a mixed-method approach, analysing satellite imagery and borrowing on ethnographic sources such as archival accounts, historical maps and colonial-era gazettes, we show how the unequal development of the city can be visualised in relation to its uneven topography.

The colonial origins of planning

In March 1791, the army of the British East India Company, under Lord Cornwallis, camped in Bangalore as it set to confront Tipu Sultan and his Mysore army. The battle ended decisively in the Company’s favour. Over 15 years later, the Company established a military cantonment in Bangalore, owing mostly to its elevation and strategic location.

The British-controlled parts were envisioned to reflect order and authority but also designed to explicitly distinguish it from the ‘native’ pettah.

Cognizant of history, Lt. John Blakiston, the engineer and route surveyor tasked with choosing a suitable site for the Civil and Military Station of Bangalore, picked the elevated ground where Cornwallis and his troops had set up camp (Mathur and Da Cunha 2006). A visionary engineer, he wanted to create an elevated esplanade where the army could march and project imperial authority. (This mile-long stretch, flanked by an avenue of trees, is today Bengaluru’s Mahatma Gandhi Road, the city’s downtown.)

The Civil and Military Station, under direct English administration, was situated east of the pettah, the part of Bangalore ruled by the princely Mysore state. The British-controlled parts were envisioned to reflect order and authority but also designed to explicitly distinguish it from the ‘native’ pettah, according to architectural historian Sonali Dhanpal. What followed was what geographer and researcher Malini Ranganathan calls “racialised improvement”, with underfunding of the pettah areas leading to inequality and exclusion in housing and infrastructure (Ranganathan 2018). These inequalities were often mediated along the lines of race, religion, caste, class, and other social differences.

In Bangalore’s rugged topography, those who were better off would live on extensively developed layouts on the higher grounds.

One’s place in the city’s social hierarchy came to determine where one lived. In Bangalore’s rugged topography, those who were better off would live on extensively developed layouts on the higher grounds. This was often at the expense of marginalised communities, who were compelled to live in densely populated neighbourhoods in low lying areas.

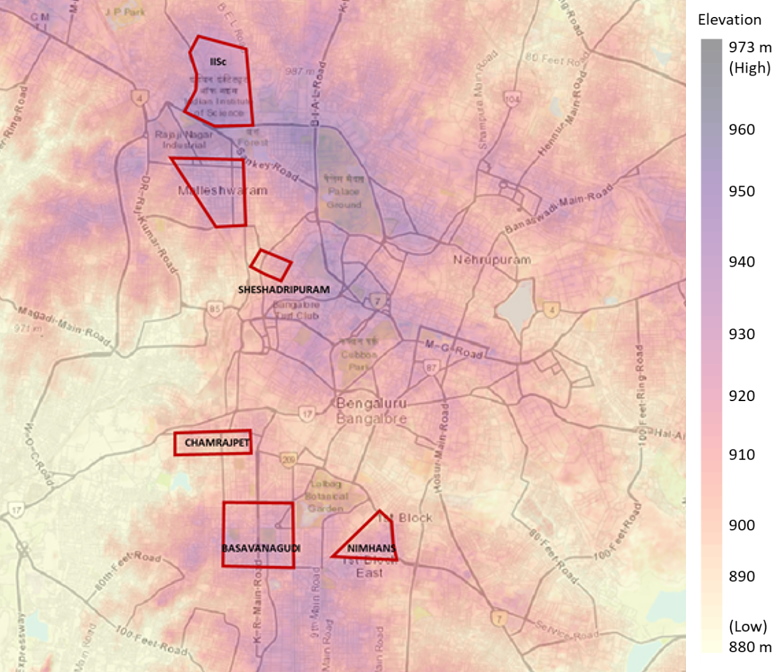

In Figure 1, we analyse the elevation data and contour lines using the 30m resolution Digital Elevation Model from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission. The elevation data and contour lines are overlaid on the current city map to visualise the relationship between the topography of the city and its settlement pattern.

Planning the CMS

Within the CMS, residential areas for the British that came up in the early 1900s, such as Cleveland Town and Richmond Town, were established on higher ground. These areas had sanitary credentials and were free from standing water and vector-borne diseases such as malaria.

By the late 19th century, the CMS had become a labour market that attracted impoverished new migrants, “who found themselves ‘set apart’ in squatter settlements”.

The Indian population that enabled the functioning of the station was housed in an adjacent area, a valley through which water flowed into Ulsoor lake, near an existing settlement called Billacully (the area is shown as Blackpully in later historic maps). By the late 19th century, the CMS had become a labour market that attracted impoverished new migrants, “who found themselves ‘set apart’ in squatter settlements from relatively more planned areas” (Dhanpal 2021). The grass cutters and horse-carers were housed in Pilka Cherry; people who built fences and barriers in Bamboo Cherry; and mat makers in Chupper Cherry. Their housing, along with commercial establishments that came up, formed the Bazaar, which is now Shivajinagar (Stephens 1914).

To meet the rising demand for water from the CMS, both in the British settlements as well as in the Bazaar, Miller’s tank was constructed in 1873. The new tank was along the same valley as the Bazaar, but at a higher elevation. The lay of the land caused water to overflow from Miller’s tank into Ulsoor lake via the Bazaar, which resulted in the Bazaar being damp throughout the year (Stephens, 1914). Knoxpet (currently Murphy Town), developed in the early 1880s for “servant classes”, too was topographically below Ulsoor lake, which kept the suburb damp. This was contrary to older settlement patterns, where villages around Bangalore were located mostly above the level of the village tank, thereby keeping them dry.

The plague and the reshaping of Bangalore

When the bubonic plague of 1898 hit Bangalore, the areas in the pettah and Bazaar were the worst affected. Bangalore’s population was reduced by over a tenth. The plague was more severe in areas of higher dampness, such as the Bazaar and Knoxpet. Indians bore the brunt with a much higher infection rate and mortality as compared with the European population residing in the CMS.

As a response to the plague, the colonial administration undertook ‘improvement’ measures to depopulate primarily the ‘native’ settlements situated within the CMS.

J.H. Stephens, the municipal engineer of the CMS during the plague, saw Millers Tank and Knoxpet as examples of the “ill-advised way in which the English have planted their more recent additions to Bangalore'' (Stephens 1922). As he noted: “While so many Mohammedens died, the plague hardly touched the English. It took some time for these people to understand that the principal cause of all the trouble was insanitary habits and manner of living."

As a response to the plague, the colonial administration undertook ‘improvement’ measures to depopulate primarily the ‘native’ settlements situated within the CMS. These measures included demolition of homes, vaccination, and forced removal to plague camps policed by military personnel.

In a part of Blackpully, which had seen the highest incidence of plague in the CMS, over 594 houses (a third of the total) were demolished and 436 families were forcefully removed. The evacuations targeted communities such as the Pariahs, Gollas, and Dhobis, who were marginalised both socially and officially and considered responsible for the plague. They were subject to force and therefore violence and conflict were commonplace (Dhanpal 2021).

The beneficiaries of the ‘improvement measures’ were Europeans and Indians of the upper castes and classes who could afford to buy plots in the new sanitised colonies.

The new planned colonies that were established had sanitary dry conditions, with planned roads, drains, and conservancy lanes. Frazer Town was planned as a “plague-proof” colony, by improving building materials, ventilation, and drainage. In addition, the topography of the land was studied to ensure the buildings were built with the least obstruction to the direction of the flow of water (Stephens 1922).

The beneficiaries of the ‘improvement measures’ were Europeans and Indians of the upper castes and classes who could afford to buy plots in the new sanitised colonies. Displaced marginalised communities were not adequately rehoused or compensated. For instance, in Knoxpet rebuilding only took place 25 years after the evacuation in 1898 (Nair 2005).

However, the British response in Bangalore was far more thoughtful than in other cities, such as Bombay where new boulevards were razed through neighbourhoods. Some efforts were made in Bangalore to prioritise poor-quality housing for demolition, provide compensation through municipal assessment and rent-free accommodation for six months. Local leaders were also engaged to ensure people’s participation to some extent. The historian Janaki Nair has described how some of the improvement measures in the CMS were more humane than in the part of the city administered by the Mysore state.

Lower classes and castes either could not afford the new housing, or were not welcome in these colonies, or slowly got gentrified out of these colonies.

Several extensions of the pettah were being developed even before the plague, due to the rising density and congestion and to house workers in the early textile mills of Bangalore. The plague prompted people to shift to these new colonies in Chamrajpet, Seshadripuram, and Malleshwaram and led to the establishment of more planned colonies such as Basavanagudi which were all on higher grounds with sanitary credentials.

These neighbourhoods were laid out in a grid format with a network of crossroads and main roads that enclosed residential plots. While the colonies of Malleshwaram and Basavanagudi housed people of different castes and religions, their layouts were caste segregated. The high value of these lands, built on elevated land and with good drainage, along with the rigid dynamics of caste, meant that only the affluent, mostly the members of the upper castes, could afford plots. The lower classes and castes either could not afford the new housing, or were not welcome in these colonies, or slowly got gentrified out of these colonies. Upper castes demanded larger plots in these colonies and wanted rules that prohibited sale or rentals to people of other castes. (Ranganathan 2018).

Caste associations, religious and political leaders, and fixers became instrumental to securing municipal benefits for the poor.

Through the years, even as these layouts generated revenues for the colonial administration, the housing needs of the marginalised communities were largely neglected. Few of the newer migrant workers, attracted by the growth of the textile industry in Bangalore into the 1930s, were accommodated in company-provided housing. Some were accommodated in low-lying lands belonging to the municipality and almost 14,000 families were left in need of housing. (Nair 2005).

Those dispossessed by the urban ‘improvement’, as well as other marginalized communities, sought alternative means to secure access to housing and livelihoods. Caste associations, religious and political leaders, and fixers became instrumental to securing municipal benefits for the poor. Religious and caste-based institutions undertook the informal sale of land to poorer groups. The “municipalization of caste”, as Janaki Nair terms it, by which caste norms and authority were accommodated into the city’s administration, became a significant means to lay claim to the city.

This led to a hybridised ‘improvement’ regime in Bangalore, where Eurocentric liberal policies were appropriated to and reinforced by indigenous hierarchies (Ranganathan 2018). As the demand for housing in Bangalore increased, the poor were compelled to develop housing in private or “unauthorized layouts.” These unauthorised layouts were typically on low-lying troughs adjoining the planned layouts.

Continued neglect

In 1945, the Bangalore City Improvement Trust Board (CITB) was established. The mandate of the CITB was to reduce overcrowding in neighbourhoods identified for “improvement” and to build residential extensions with modern infrastructure and public amenities. Ranganathan argues that the CITB, an unelected body comprising experts and technocrats, helped consolidate class and caste privileges, by continuing to neglect the interests of marginalised communities.

Even when there was a shift in political regimes, the underlying discrimination in housing endured. Between 1945 and 1973, the CITB developed over 65 extensions distributed over 60,000 sites and undertook 160 improvement schemes. Plots for “good bungalows with compounds meant for well-to-do persons” were developed on prime property procured from the Mysore royal family’s palace estates in Sadashivangar and Jayamahal to the north. Plots in Jayanagar, in the south, was “mainly meant for the middle class,” with priority for government servants, industrial workers in Public Sector Undertakings (Ranganathan, 2018). The CMS lands became institutional lands housing government offices. The PSUs which came into Bangalore, such as HMT, BEL, were also placed on higher grounds.

The inadequate provision of housing for the poor led to the proliferation of slums, with the government of Mysore estimating in 1963 that 10% of Bangalore’s population lived in slums (GoM 1963). The definition of slums in the Mysore Slum Clearance Act of 1958 makes a specific reference to low-lying areas:

“any area that is or likely to be a source of danger to health, safety or convenience of the public. . .by reason of the area being low-lying, insanitary, squalid, overcrowded, or [faced with] dilapidation, overcrowding. . .narrowness,. . .lack of ventilation, light or sanitation facilities, or any combination of these factors, [and is] detrimental to safety, health or morals”

This becomes evident when the topography of the city is overlaid with satellite imagery. For instance, some parts of the Vyalikaval-Gutahalli area are located in the trough, sandwiched between the planned upper-class colonies of Malleshwaram and Sadashivnagar. The density of the built-up area is visibly different in this area if you look at the satellite image.

The legacy of the top-down urban planning and improvement discourse introduced through the CITB endures through the popularity of parastatals in Bangalore, unelected expert bodies that continue to determine several aspects of urban policy, including housing. The Bangalore Development Authority, established in 1976 took over the role and functions of the CITB and continues to be the principal planning authority for Bangalore.

Over 120 years after the plague epidemic, the topography of the city still shapes land-use planning, but in very different ways. The explosive growth of the city, especially following the IT boom from the 1990s onwards means that land is increasingly scarce. The previously-shunned lowlands now house IT parks and high-end housing. While lowlands are no longer a threat as it was during the plague times, due to improved construction practices, building materials and better sanitation, they still face issues of flooding during heavy rains.

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Krishnachandran Balakrishnan and Pratyush Tripathy of the Geospatial Lab in the analysis. This research was conducted with support from the PEAK-URBAN research consortium. (https://www.peak-urban.org/)