In February 1897, six months after the first case of bubonic plague was found in colonial Bombay, a thousand people were fleeing the city each day, spreading the disease throughout colonial India. Residents in central Bombay locked themselves up in their flats afraid that plague officers would come knocking. Children were rounded up in ambulances if they seemed ill, often against the will of their relatives. By 1921, the plague would kill 10 million people throughout India.

But plague was not colonial India’s only problem—cholera, smallpox, malaria, tuberculosis, vague “fevers,” and plain old starvation were constant sources of death. Between 1896 and 1921, malaria may have killed 20 million people, twice as many as the plague did in the same period. Some 12–20 million people perished in India during the influenza pandemic of 1918.

Throughout the history of British India, 23–35 million people died of cholera epidemics and already by 1900 over 30 million people had died of famine related causes. All of these numbers are quite likely to be underestimates than overestimates due to the difficulty in gaining accurate figures and the politically motivated disinclination to report.

Surprising, then, that it was the bubonic plague which was declared the crisis to deal with in colonial Bombay. Then, as now, only one out of a handful of deadly afflictions, the one that most directly threatened commerce, trade, and the accumulation of capital—was identified as a ‘crisis.’ The plague would be the Bombay government’s priority for the next two decades. Once capital and labour started to flee the city in the plague’s wake, the government undertook unprecedented efforts to bring them back in. The wheels of commerce had to be made to turn once again.

When history seems to be repeating itself, it is perhaps only natural to look to the past. But some of the lessons on offer are misguided.

Ever since Covid-19 has interrupted life in India, media references to both the plague of 1896 and the influenza pandemic of 1918 have become commonplace. India’s lockdown has produced disturbing scenes reminiscent of an earlier era: masses of migrants returning home on foot, a growing crisis of hunger alongside the cruel irony of godowns overflowing with 70 million tons of food surpluses, arbitrary powers usurped by police patrols across the country, and even the revival of plague-era laws like the Epidemic Diseases Act of 1897.

In the nineteenth century, as in the present, the eventfulness of the chosen crisis displaced attention away from longstanding structural vectors of inequality and mortality. The force of the market, ideologically and materially, determined which events could be narrated as a crisis and which could not, just as it determined the government’s priorities in managing it. When history seems to be repeating itself, it is perhaps only natural to look to the past. But some of the lessons on offer are misguided.

For example, some argue that the key takeaway from the plague of 1896 is that lockdowns, while inconvenient, are essential to controlling contagion. They forget that lockdowns are measures of last resort undertaken when public health infrastructures are wanting because they are at capacity. Others write that past epidemics teach us that we ought to be patient—“trust history, this will pass”—since microbes and humans have long shaped each other in human history; an argument that shades into social Darwinism.

But by far, the worst line of argumentation is a very subtle one that places diseases and epidemics outside of “the economy.” Such an argument assumes that diseases are simply products of nature, devoid of human imprint. As such, diseases interfere with an individual’s ability to earn a living or a society’s ability to pursue economic growth. Since Covid-19 has struck, far too many will be “pushed into poverty” and the best we can do is to mitigate their hunger and pain with relief until we can return to ‘normal.’ In this argument, poverty is a result of disease.

Historians have found a key factor that accounts for India’s disproportionately high rates of disease mortality: the simultaneity of illness with hunger.

Instead, the colonial past might offer different lessons. Primarily we learn poverty is not just a result but also a causal condition for much neglected endemic and epidemic diseases to thrive. Together, poverty, hunger, and illness, are the common results of a political and economic system biased towards the more privileged in society. Therefore, sporadic crisis episodes like the plague, the flu pandemic, and even Covid-19 burst onto a scene already ravaged by quieter and steadier crises of cholera, malaria, hunger, and gruelling poverty.

If we return to the history of pandemics with this broader understanding, what more can we learn about our present predicament?

Pathogens Need Poverty

The first lesson of the health crises of a century ago is that most illnesses struggle to act alone. To produce mass mortality, pathogens require the compromised economic conditions that thrive along commercial networks. In other words, pathogens feed on chronic deprivation.

Colonial India’s mortality rates from communicable illnesses such as cholera were much higher compared with most of the world. For instance, in Britain, only 150,000 people died of cholera in the entire nineteenth century, a mere fraction of India's cholera deaths. Over the following century too, India maintained a global lead in disease mortality, due to a callous disregard for working class lives and the systematic neglect of public health that was just as remarkable in the colonial era as it is now. How can we explain this?

Historians have found a key factor that accounts for India’s disproportionately high rates of disease mortality: the simultaneity of illness with hunger. Both cholera and influenza thrived when prolonged bouts of hunger compromised the body’s defences, leading to large discrepancies in mortality between hungry and sated populations. About cholera epidemics in the nineteenth century, David Arnold writes that mortality doubled or tripled when cholera coincided with famine. Their “lethal synchronization” caused the highest recorded number of cholera deaths in Madras in 1866 and 1877 and in Bombay in 1877. Cholera mortality declined in the early 1900s but once again saw an upsurge during the Bengal famine and Partition in the 1940s. Similarly about the 1918 flu pandemic, Mike Davis finds famine and disease “exquisitely synchronized,” The resultant grain hoarding by traders meant inaccessible prices for India’s labourers. India’s mortality rate, especially in Bombay’s environs, made an especially large portion of global flu deaths.

While famines were said to be a result of “natural conditions” like drought, it was in fact the changing social systems of ownership and control that alienated cultivators from basic entitlements like food.

If hunger was a predisposing condition to disease mortality, then sadly, hunger was not hard to produce. The colonial government’s gradual erosion of the rights of smaller cultivators and the promotion of cash crops spelled for many the loss of access to livelihood and to food crops. As a result, there were regional famines in colonial India in every decade of the nineteenth century. While famines were said to be a result of “natural conditions” like drought, it was in fact the changing social systems of ownership and control that alienated cultivators from basic entitlements like food.

To cope, several cultivators fled for the cities, even as they maintained connections in the villages. This protection strategy gave them some safety. They could flee the city in periods of downturn following speculative business cycles, like at the end of Bombay’s cotton-led boom in the 1860s. When the famines in the 1870s killed some 10 million people in the countryside, they turned back to Bombay for relief.

But famished migrants got very little relief from a callous government eager to motivate cultivators towards industriousness rather than dependency on the state. Business owners refused to hire these ‘unskilled’ labour or invest in training them. Relief camps were governed by constant calculations: ‘what is the bare minimum amount of grain we have to give to keep them alive but still motivated to work?’

Thus, as the government and its allies were busy debating whether and what they owed workers and famished migrants, India’s working classes struggled to eat. In a climate of several endemic diseases, before antibiotics or the understanding of how pathogens work, compromised individuals became carriers who threatened the health of even the well-fed.

Thus, related to the first historical lesson that pathogens require compromised economic conditions, conditions created by the increase in commercial opportunities for some, is the fact that the poverty of one person produces disease in many. As a result, famines throughout the late 1800s coincided with repeated endemic outbreaks in colonial India.

Corrupting Public Health

The second lesson of colonial-era health crises is that moneyed classes opposed public health investments that benefitted the population as a whole. By the late nineteenth century, worldwide medical advances helped identify germs, rather than miasma or bad air, as the cause of most illnesses. But in colonial India, the belief in miasma and other discredited explanations for epidemics continued. While preventative public health measures like water management were starting to take hold in other parts of the world, in India ‘public health’ narrowly connoted post-outbreak disease management rather than anticipatory population-level planning.

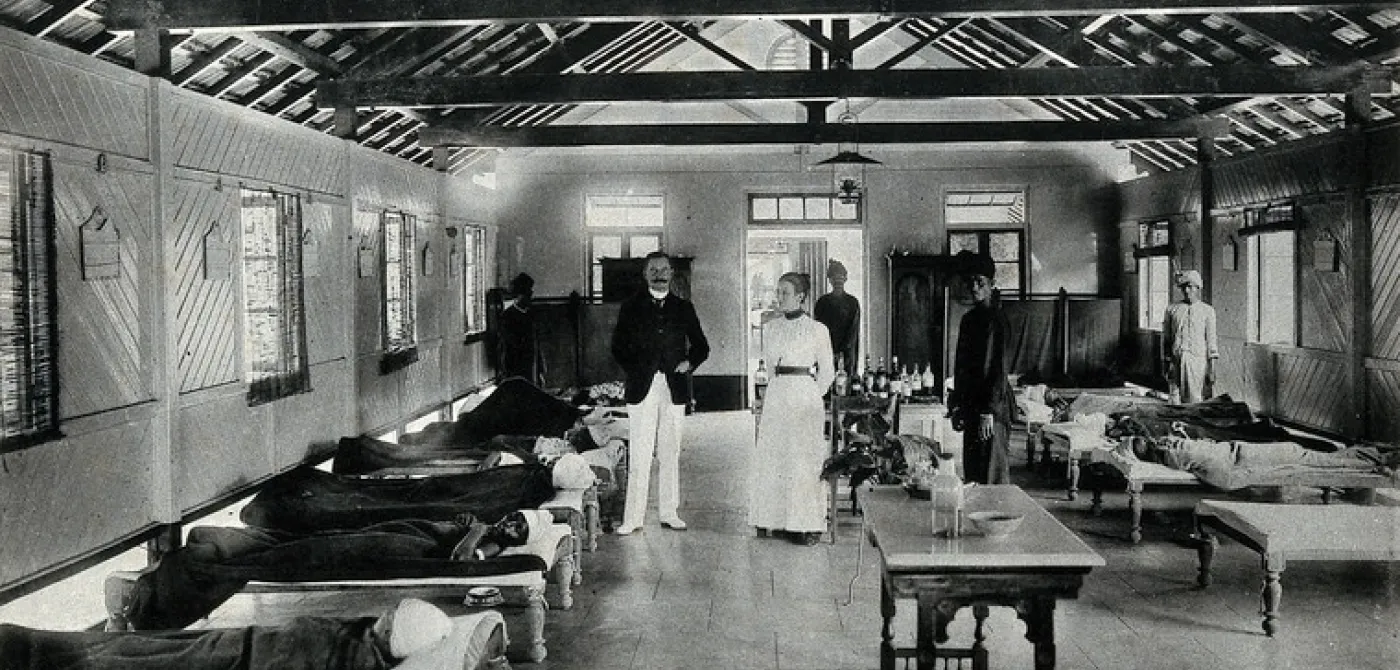

Wanting primarily to defend its colony, the colonial regime invested selectively, sanitising areas crucial to colonial rule, like military cantonments, but elsewhere encouraged Indians to look after their own well-being.

Historical common sense suggests that the colonial regime’s low public health expenditures was a result of its self-interestedness. Wanting primarily to defend its colony, the colonial regime invested selectively, sanitising areas crucial to colonial rule, like military cantonments, but elsewhere encouraged Indians to look after their own well-being. Disproportionately low investments in sewage, drainage, and water supply lines meant that colonial India did not obtain the public works that all but stopped water-related illnesses like malaria or cholera in what would become the developed world. After all, British colonial rule was an external force meant to extract and exploit, not invest in a sustainable future.

But if we ask exactly why the colonial state failed to invest, it reveals a much more insidious story of how power works. In 1885, a year in which cholera killed many inhabitants, the British Medical Journal reported:

Bombay, far from being a poor city, is perhaps the richest in India; and it is notorious that its wealthy inhabitants, being the most litigious people in the East, spend yearly in the law-courts, mostly in frivolous suits, enormous sums of money, which would be better spent in cleansing the city, where they live and prematurely die.

This complaint would become part of a longer pattern of volleying blame between the colonial regime and the Indian elite for exactly who should bear the burden of developing the country. But in that tussle, both sides won by deferring and displacing expenditures. The poorest of Indians lost.

When plague arrived in Bombay in 1896, the panic in one of India’s leading commercial hubs severely threatened the economy of the colony. The city came to a grinding halt.

Take, for instance, the difference in cholera rates between the cities of Bombay and Calcutta in the late nineteenth century. Capital city Calcutta, with its large population of colonial officials, constructed water supply and sewage systems, causing cholera rates to drop between 1870 and 1900. By contrast, when Bombay's municipal commissioner Arthur Crawford proposed an extensive drainage system, he was forced to resign after landholders protested against the proposed tax to cover the expenditures. As a result, Bombay’s cholera rates remained higher than Calcutta’s. Rather than share in the burden of building a public-goods regime that might have mitigated some of the underlying causes of epidemics, the wealthy avoided such investments, be it housing for their labourers, fair compensation for work, or sources of clean water.

In sum, Indian aristocrats, landlords, financiers, and industrialists did much to determine state agendas, colonial or otherwise. They blocked public health when it would cost them. But there could be one exception to this pattern. If the occasion of a crisis could be made lucrative, even the moneyed classes could take interest in ‘the health of their city.’

The plague of 1896 was that exception. When plague arrived in Bombay in 1896, the panic in one of India’s leading commercial hubs severely threatened the economy of the colony. The city came to a grinding halt. Factories and businesses voluntarily shuttered. Fixed costs or investments made in industrial production sat idle. Some 300,000 migrants left Bombay in 1897, making even rent-seeking a frustrating endeavour, given the dearth of the labouring and indebted classes.

[When] the flu pandemic arrived alongside a drought in 1918, it spread especially through the city’s ‘slums’ where the poorest were forced to contend with both illness and hunger all at once.

To restore commerce, the city had to be cleansed of contagion. In 1898, the City of Bombay Improvement Trust was formed to restore the ‘sanitary credit’ of the city. Even though rural mortality was higher, focusing on the city showed how the Trust was more eager to address the ‘crisis’ of stalled commerce rather than public health. Over the next three decades, the Trust corrupted the meaning of ‘public purpose.’ Guided by the discredited miasma theory of contagion, it acquired properties so as to widen thoroughfares and ‘let light and air in.’ The Trust spent public money to overcompensate landlords who produced hypothetical building plans to claim higher compensation on the grounds their plots could have fetched higher sums.

The city’s capitalists and officials thus repurposed an institution formed to deal with a public health disaster into one that made the rich even richer, even as they failed to address Bombay’s housing and sanitation problems. As a result, once the flu pandemic arrived alongside a drought in 1918, it spread especially through the city’s ‘slums’ where the poorest were forced to contend with both illness and hunger all at once. By the 1920s, the health of the city meant anything but the health of its poorest residents.

Manufactured Epidemics

Using this historical analysis, we learn that the production of widespread poverty, the resultant malnourishment and hunger, and the neglect of public health investments together form the conditions under which India’s real public health disaster is created time and time again.

Our current Covid-19 crisis is not a singular event. It is one effect of a decades-long process that has produced impoverishment, hunger, and ill-health, all at once.

Back in 1897, just before Bombay’s Improvement Trust was formed, the British Medical Journal wrote that “habitual and not spasmodic sanitation is the only real safeguard against epidemic disease.” In colonial India this would have required public investment and future-oriented planning. Even in the decades after independence, advocacy for such planning has had to swim upstream against the interests of the propertied classes who could (and did) force the privatisation of public health.

Our current Covid-19 crisis is not a singular event. It is one effect of a decades-long process that has produced impoverishment, hunger, and ill-health, all at once. Just as in the health crises of a century ago, illnesses do not act alone. To produce mass mortality, pathogens require mass poverty. As we have also seen, there is no solving of health crises when moneyed classes oppose public health investments that benefit the population as a whole. Not just in India but across the world, historically racialised, minoritised, neglected, and impoverished communities disproportionately bear the burden of disease, including Covid-19. Mass hunger will certainly be the result of a poorly designed lockdown in India, but that so many were so close to the brink of starvation reveals just how deep the structural vectors of inequality and mortality already were.

We need to tackle the underlying structural inequities that breathe life into every natural disaster. Ultimately, pathogens are not outside of the world of commerce we have created. They are its effects. It takes human effort to make pathogens work. Cholera and malaria thrive where public water works are neglected. Influenza thrives under conditions of starvation. Malnourishment is the perfect breeding ground for a whole host of illnesses. To produce malnourishment, one has to neglect or mystify decades-long agricultural crises, farmers demands, and the basic right to food, and health. To be so very vulnerable to viral illness like Covid-19, one has to tether pharmaceutical industries to endless profit rather than public welfare.

If we have learned anything from the past or the present, it should be that only well-funded public health systems, where public purpose is not corrupted by private ambition, can properly mitigate outbreaks.

Decades of disinvestment and neglect mean that even after independence, India’s disease burden continues to be disproportionately high, even absent Covid-19. Just as in the colonial period, India’s underdevelopment is manufactured, a product of neglect and failure to take seriously the need for genuine public goods and the need to discipline the self-interestedness of private interests. For-profit medical entrepreneurship is celebrated as a national achievement and has produced worse health outcomes than in well-funded public institutions driven by democratically scrutable metrics. India remains one of the worst places in the world to get sick. It continues to produce an outsized number of deaths per disease outbreak, with illnesses that have all but disappeared from the ‘developed’ world regularly wiping out tens of thousands of inhabitants a year.

India has the largest number of undernourished people in the world. Malnourishment is India’s “silent emergency,” with higher child malnourishment rates than in sub-Saharan Africa and five times as much as in China. Tuberculosis claims the highest number of lives in India. One-fifth of maternal deaths and one-quarter of child deaths in the world occurs in India. Amongst children under five, India has the highest mortality rates worldwide. India spends less than 1.5% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health, one of the lowest in the world even amongst developing countries.

If we have learned anything from the past or the present, it should be that only well-funded public-health systems, where public purpose is not corrupted by private ambition, can properly mitigate outbreaks. As we have seen with the coronavirus outbreak, the relentless pursuit of profit in some parts of the 'developed world' provides no model to emulate. Rather, India’s own state of Kerala reveals that true development entails a strong public goods regime, one that protects all of its citizens from premature death.

Pursuing prevention is the truest meaning of public health, one that would require acknowledging what one analyst, V Geetha, has correctly noted: “We cannot tackle the coronavirus without tackling capital and its depredations.” If only the political will could be found.