On the morning of 4 December, the director-general of the Assam Rifles inaugurated the fourth day of Nagaland’s annual Hornbill festival. The Naga organisers rolled out the red carpet and honoured him with a traditional embroidered shawl. The invitation had gone out to him as part of an attempt by the current generation of Nagas to reconcile with the very paramilitary unit engaged, until a ceasefire in 1997, in bloodshot ‘operations’ to suppress the Naga demand for the right to self-determination.

Later in the day, after the chief of the Assam Rifles had imbibed the rich cultural performances at the festival, the 21st Para Special Forces and the Assam Rifles began an ambush in Oting village in Nagaland’s Mon District, that left at least 14 innocent Naga civilians dead.

The men waylaid and murdered in Nagaland were coal miners returning home in a pick-up van. The dust and ashes that covered their faces was not guerrilla camouflage – as it might have been decades earlier – but the bodily display of their precarious existence at the bottom of the extractive capitalism that mars the hills. The official narrative is that the army took them for armed insurgents on the prowl. With ceasefire protocols apparently eluding them, the Naga labourers were shot “without warning”. “Direct marise (they shot right at us)”, one of the two survivors related from a hospital bed.

In Nagaland’s legal landscape, the difference between a ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ state-killing depends on the discharge of “due warning.”

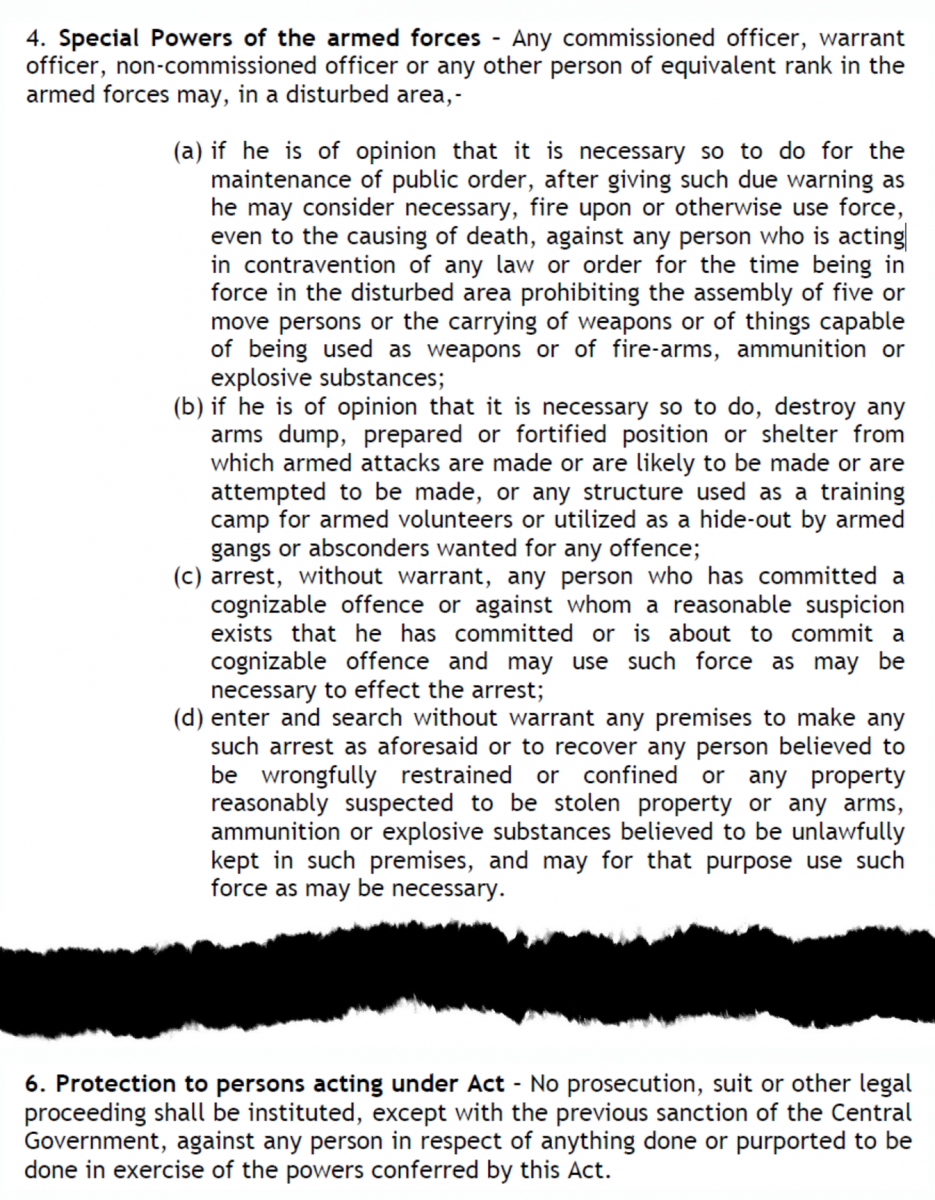

‘Without warning’: this point is macabrely crucial. The law, in the form of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), permits the killing of any Naga on the mere ground of suspicion. But such killings must be preceded with, to quote the act, “due warning.” In Nagaland’s legal landscape, the difference between a ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ state-killing depends on the discharge of “due warning.”

Once the army realised their mistake — if indeed it was a mistake — and after what the villages said was a failed bid to cover up the killings, officials went into a political overdrive. Apologies were uttered, condolences shared, statements made in Parliament, explanations of mistaken identity were offered, and the customary probe ‘at the highest level’ assured. Grieving next-of-kin were offered money as compensation — a most abject form of justice that reduces mourning, loss, and trauma to a cash equivalence, payable as the official state acknowledgment of guilt. The offer was declined by the Oting Village Council. Instead, they asked for justice.

Most of the Naga experiences of state violence remain untold. The survivors struggle to find words to describe them and remembering makes life unliveable.

Many Nagas, especially the elders who lived through the worst of army operations prior to the 1997 Indo-Naga ceasefire, are overwhelmed by their personal recollections of comparable incidents. During my two-years of fieldwork in Nagaland, I heard many such horrific stories. It was impossible not to see the sorrow and trauma of being subjected to brutal state violence. Words such as agony, misery, suffering, torment, or pain hardly begin to describe the traumatic experiences that have, over time, affected almost every Naga household as AFSPA-bolstered armed forces swooped, combed, and devastated villages. Many such incidents took place in the murky past and countless lives were lost, but rarely made headlines outside the hills. Civilian deaths were hardly worth reporting, accepted as they were as the ‘collateral damage’ of putting down the Naga insurgency.

In Naga areas, silence has long been a coping strategy. Most of the Naga experiences of state violence remain untold. Survivors struggle to find words to describe them and remembering makes life unliveable. However, possessed by their own traumas, many Nagas now find themselves identifying with the victims of the Oting ambush and the surviving kin.

More so, when there are signs that presage the beginning of yet another dreadful chapter of militarisation of this borderland. Oting abuts the Indo-Myanmarese border; and a few days after the killings, Myanmar security forces — involved in brutally quashing resistance to military rule — killed 11 people when they assailed a village just across the frontier in that country’s Sagaing region of which the Naga self-administrative zone is part.

Voices of agony

This time around in India, the reaction to state violence is different. There is no silence. From the streets of the North East to social media to the floor of the Lok Sabha, voices of protest, disgust, and anger roared.

If the ambush was a pre-mediated test to gauge how contemporary Naga society would react to wanton state violence in preparation for an all-out, Kashmir-like take-over to crush all opposition and annul existing special constitutional provisions —which is one theory doing the rounds — the union government will be disappointed with the reaction. Naga tribes, apex bodies, and civil society organizations have transcended their usual differences and united in a refrain of mourning and condemnation. The Hornbill Festival was cancelled. Protesters marched, shouting slogans to ‘Repeal AFSPA’. Naga writers and poets transmitted the horrors to the rest of India and the world.

The entirety of Naga history has been summoned to break its silences […] to submit its traumatic experiences to scales of justice that overflow state law.

Neighbouring communities such as the Kuki and the Meitei, who otherwise often live at odds with the Nagas, came forward to condemn the incident. The chief-ministers of Assam, Manipur and Meghalaya joined the Nagaland chief minister in demanding the repeal of AFSPA. Reportage in a range of outlets from The Times of India to the New York Times called out the Indian state and army for its atrocity and callousness. Trans-tribal, trans-ethnic, pan-Indian, and global solidarities were braided in the darkness of state violence.

The entirety of Naga history has been summoned to break its silences, to relive its memories of AFSPA, to share them, to speak in languages hitherto untranslated and unheard, to submit its traumatic experiences to scales of justice that overflow state law. With the state and army now hauled before the court of humanity, of dignity, of what it means to live in democratic India, it is not about the Oting killings alone, even as the grief of the surviving kin must retain centre-stage. This upscaling of justice is a prerequisite for any meaningful discussion, for the law in Nagaland itself bleeds violence.

Legalised lawlessness

AFSPA was modelled on Armed Forces (Special Powers) Ordinance of 1942, a colonial-era law enacted to suppress the Quit India Movement. By a stroke of the governor’s pen or by declaration of the union government, AFSPA reduces people living in an area declared as ‘disturbed’ to suspicious bodies liable to be exterminated.

First promulgated in 1958 to suppress the Naga uprising, AFSPA has since blanketed the Naga hills (and several neighbouring and nearby states) in legal darkness. AFSPA allocates military and paramilitary forces with the lethal labour of shooting to kill, not just in an encounter or counter-insurgency operation, but anywhere, anytime, and anyone on the mere ground of suspicion. The near absolutel legal impunity for the armed forces leads us to the dark underbelly of modern state power and violence.

The legal order that enclosed the Nagas into the state, first in the colonial, then in its postcolonial guise, always kept apart the ideas of law and justice.

As a law, the AFSPA has a clear affinity to state violence; an affinity that is regularly picked up by journalists, but, who in their focus on specific atrocities, often gloss over the entrenched historical and political structures that enable these atrocities to only accumulate.

To the Nagas, modern forms of law have never provided protection of life and property or dispensed justice. The legal order that enclosed the Nagas into the state, first in the colonial, then in its postcolonial guise, always kept apart the ideas of law and justice. It is through this permanent separation that the dehumanisation of the Naga began, then horrifically consolidated itself as second nature for just about anyone posted to the Naga hills: be they colonial officers, postcolonial state bureaucrats, army generals and captains, or foot soldiers.

Early British administration of the Naga hills was predicated on a colonial understanding of the inhabitants as ‘primitive’ and ‘savage’ with a clear predilection for reckless and unpredictable violence. “Bloodthirsty, treacherous, and revengeful all Nagas, even the best are,” so were the Nagas introduced in 1881 to an august gathering of officers and scholars in London.

What particularly appalled (but also clearly fascinated) colonial officers was the so-called Naga headhunting tradition. One official saw it as “second nature to the Naga to seek for human heads”, while another remarked with disgust that the Nagas would cut off heads “without any provocation or pre-existent enmity, merely to stick up in their fields to ensure a good crop of grain.” Colonial officers’ understanding of head-hunting, its social and ritual implications, was evidently simplistic and limited to it confirming – to them – Nagas’ barbarity. Subsequently, the trope of Naga headhunting justified British ‘pacification’: the euphemism used for conquest and violent domination of the Nagas.

“It is always difficult to know how much [collective] punishment to inflict.”

So long as the Nagas occupied land considered barren, they were marginal to the exchequer — and by extension, to colonial interest. But their recurrent raids on the fertile Assam plains, where lucrative tea plantations were coming up, risked revenue and commerce. The earliest engagements between the British and the Nagas revolved around curbing these raids.

Colonial officers resorted to punitive expeditions and collective punishments, usually by burning to ashes entire Naga villages, granaries included. Such collective punishments were highly arbitrary, and the indiscriminate destruction they wreaked discomforted even British officials. “Besides the “grand clans” in each village, there were in each portion many sub-divisions adhering to one side or the other; hence indiscriminate burnings of villages should be avoided as injuring friends as well as foes,” one of them wrote in the 1850s. And yet, as late as 1947, Charles Pawsey, the district commissioner of the Naga hills, upon returning from a ‘punitive’ expedition against what he called, “bold bad head hunters,” wrote that: “It is always difficult to know how much [collective] punishment to inflict.”

It is in these arbitrary collective punishments of the colonial era that we find antecedents of AFSPA in the hills.

A despotism of law

The second phase of British-Naga relations began with the creation of the Naga Hills District in 1866, although at first this was merely a proclamation and a police outpost in the foothills. In 1878 the colonial headquarters shifted up to Kohima, inaugurating a more permanent occupation of the Naga hills.

Colonial rule allowed for the continuous conquest and expansion under the guise of ‘civilising’ the Naga by ‘pacifying’ them.

Formally, the British governed the hills indirectly through a policy of ‘non-interference’, grounded in colonially sanctioned ‘traditions’ and ‘customs’. In actual practice, the colonial state operated as a protection racket that offered protection to Naga villages in return for annual house-tax and regular 'coolie-services'. The protection offered was claimed to be against incidental raids by villages outside immediate colonial territory. But primarily, it was against the violence the colonial state itself threatened to deliver.

What is more, colonial rule allowed for the continuous conquest and expansion under the guise of ‘civilising’ the Naga by ‘pacifying’ them. This became known as the forward policy. This move ‘forward’ into the hills was not based on a clearly defined legal order and jurisdiction. Instead, colonial rule in the hills remained highly personalised and largely depended on arbitrary interpretations, judgments, and ambitions of local officials, who were given summary legal, executive, and punitive powers.

There were only British officers empowered with the authority to arbitrate over life and death — the same authority with which AFSPA-backed soldiers walk across these hills today.

Crucially —and here we find another historical antecedent of AFSPA — the colonial state required no formal record of evidence before meting out punishments. No laws controlled and circumscribed state violence on people and property. Nor were colonial officers ever held accountable for the death and destruction they inflicted on Naga villages, not even when they themselves boasted about it in their tour diaries. The ‘rule of law’ translated into keeping control and order on the frontier, by whatever means deemed necessary, incurring any human costs.

The same absence of legal authority and judicial procedure applied to court cases. There were no lawyers or trained judges, not even a flimsy separation between the judicial and the executive branches of government. There were only British officers empowered with the authority to arbitrate over life and death — the same authority with which AFSPA-backed soldiers walk across these hills today. The words of colonial officers masqueraded as the law and their judgments as justice.

Invariably this form of administration had to be considered as exceptional. This was the colonial rationale of classing the Naga hills formally as an ‘excluded area.’ To be clear, this designation meant exclusion not from colonial control and rule, but from the universality of the law, from civil and political rights, and from impartial justice. The Nagas were subject to state action, including corporeal and capital punishment, but without any resort to law and justice. Their excluded status made them more killable.

A permanent state of exception

In its origins and rationale, the AFSPA was not simply a legal reflex to the Nagas’ rejection of the Indian state in the decades following India’s independence. It was also not merely occasioned by incomplete decolonisation. Nor is its continued presence purely the working of unchecked power, clothed in the trappings of the law. The ease with which colonial structures of exclusion, violence, and injustice transitioned to India’s constitutional democracy leads us to a much deeper and darker realisation.

It was through the state of exception of AFSPA that the Indian state expanded, by brutal means, its control over the Naga uplands at a time when its legitimacy to govern was questioned.

It was Walter Benjamin, and most recently Giorgio Agamben, who revealed how the modern state everywhere is grounded in laws that originate from violence and exist by violent means. In a self-declared moment of crisis, these laws allow legalised violence on its own citizenry. The legal and the lethal go hand in hand.

Agamben theorised this affinity between law and state violence against an identified class of citizens as the “state of exception” — where governments assume power and authority in ways that extend beyond the law. In a state of exception, the law is suspended to protect and expand state authority and power. In the process, the boundary between the inside and the outside of the law is blurred.

This reading of the state of exception applies to AFSPA which, after all, is a legal device invoked precisely to suspend the rule of law in the interest of the Indian state, whose authority it is designed to protect. It was through the state of exception of AFSPA that the Indian state expanded, by brutal means, its control over the Naga uplands at a time when its legitimacy to govern was questioned.

For Agamben, the most evocative example of the state of exception was Nazi German. Drawing on its example, he wrote how this exception “allows for the physical elimination not only of political adversaries but of entire categories of citizens who for some reason cannot be integrated into the political system.” (2005: 2-3).

AFSPA’s permanent association with the Naga is indicative of their incorporation into the Indian nation-state as secondary citizens, as rights-deprived subjects.

With the progression of modern governance, states of exception are decreasingly exceptional or temporary, Agamben writes. Instead, they have become a permanent tool of governance and control. The permanence of the exception is perhaps nowhere clearer than in its application to the Nagas. AFSPA is both older than the state of Nagaland, which was created in 1963, and continues irrespective of changing ground-realities, including almost 25 years of a ceasefire.

The state of exception remains in force against the Nagas as a category, even when violent insurgency has long given way to ceasefire and insurgent cadres are confined to designated ceasefire camps. The law erases the legal individual status of the Nagas and reduces them from right-bearing citizens to killable objects. AFSPA’s permanent association with the Naga is indicative of their incorporation into the Indian nation-state as secondary citizens, as rights-deprived subjects.

Relatedly, the AFSPA exists outside of the democratic process. While Nagas vote for state and national elections every few years, the question of AFSPA is never on the ballot. Nagas are not allowed to have an opinion on it, even less to vote about its enforcement on them. Neither are their political representatives, whether in the state assembly or Parliament, empowered to amend or revoke this law. The prerogative of AFSPA, pace Agamben, lies with the ultimate sovereign, namely the union government in New Delhi.

In its legalising of nonexistence and in its location outside of the democratic process, AFSPA therefore poses disturbing questions of what Indian democracy is and what it becomes when it scales the Naga hills.

Breaking the silence

Whatever the relationship between law and violence in India, the Nagas do not need Benjamin or Agamben to be aware of the unaccountable violence from AFSPA’s state of exception. This knowledge is both emplaced and embodied in their postcolonial history.

With the Oting killings, the Nagas are made to realise, yet again and with unmistakable clarity, their precarious existence.

Memories of this violence hang thick and grief-laden over Naga villages. These memories are forced onto the surface every time a new atrocity is committed. With the Oting killings, the Nagas are made to realise, yet again and with unmistakable clarity, their precarious existence at the threshold where the inside and the outside of the law meet to enable unspeakable violence.

This time, the Nagas daringly refused their voices to be curbed or threatened into silence by the state threat of more violence. They have begun to tell their stories and speak against the law. The non-Naga voices joining in chorus contribute to its elevation into a symphony of resistance, united for the release of justice from its incarceration by AFSPA.

We must avoid the shortcut of putting the blame on the particular army personnel involved. Those who fired the deadly shots are ultimately marionettes.

On a final note: in talking about what transpired in Oting, we must avoid the shortcut of putting the blame on the particular army personnel involved. Those who fired the deadly shots are ultimately marionettes, perhaps even victims themselves. They were assigned the unenviable lethal labour in relation to those classed by the state as legally non-existent and therefore ‘killable’ with the sanction of the law. When the law constricts justice by defining areas as permanently ‘disturbed’ and its inhabitants as permanently ‘suspect’, tout court, as the AFSPA does, this will inevitably influence soldiers’ attitudes towards Naga bodies.

The standard statist justification is that AFSPA maintains law and order, that talk about its repeal can only take place after the vexed Indo-Naga conflict is definitively resolved. These arguments have long run their course. For any sort of peace to finally prevail the repeal of AFSPA must be a prerequisite, not an ‘achievement’ or ‘reward’ the Nagas must earn by surrendering their politics and dignity.