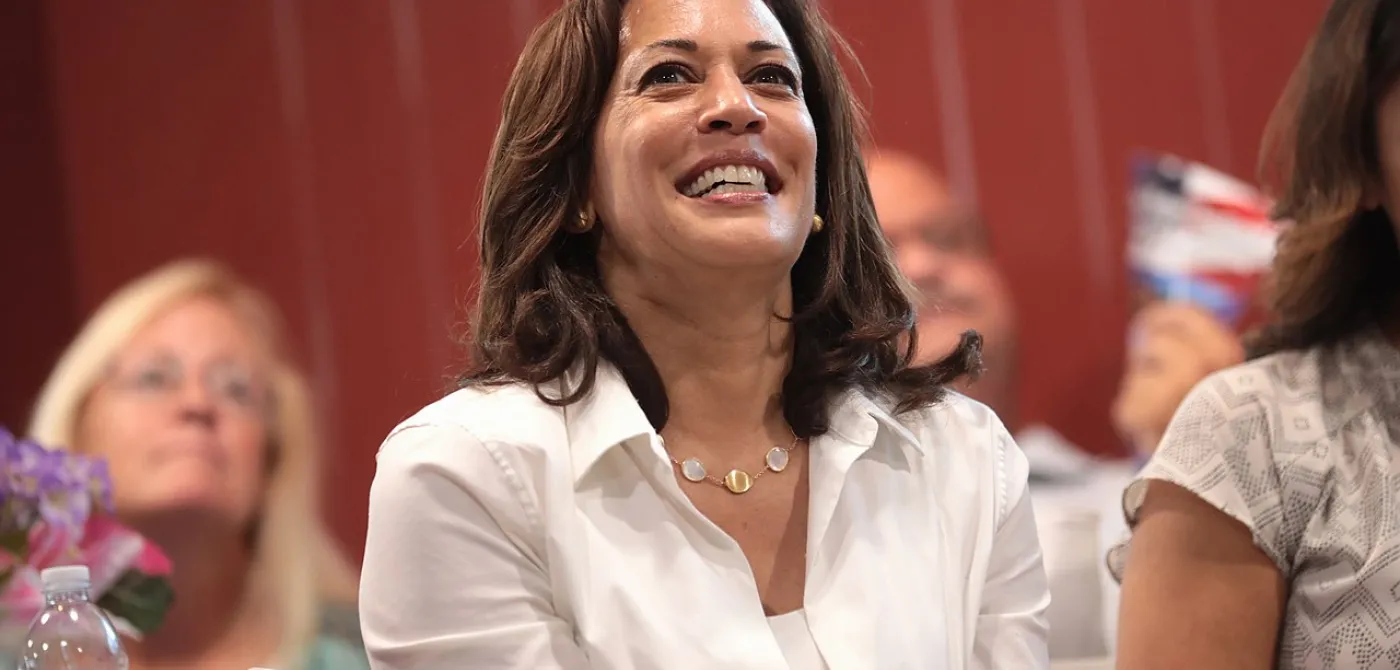

On the evening of 19 August 2020 Senator Kamala Harris created history when she was officially nominated as the vice-presidential candidate of the Democratic Party. Despite its status as the world’s oldest democracy, the United States has never had a woman president or a vice-president and just three significant woman vice-presidential candidates ever.

Harris’ part-Indian parentage had the Indian media scrambling to describe, explain, identify to its readers this relatively unknown candidate. In the first week, they ran stories about her Indian connections and family: the adventurous mother who went off to study in the United States of the 50s and stayed back to fight for civil rights and do cancer research, the progressive grandfather who bucked custom to send his eldest daughter to a foreign country on her own, the fond aunt breaking coconuts at a Chennai temple in her name.

A sense of excitement and possibility because of her India connection has largely pervaded the Indian reporting. Harris herself sent a thrill down the spines of South Indians when she referred to her chittis (Tamil for mother’s younger sisters) alongside “aunties, uncles, and nieces” in her acceptance speech. But in the United States, Indian Americans are not so sure.

Part of the problem is her mixed race.

“If we desis are honest with ourselves, we know that we are not the most open to cultures of 'otherness'.”

Kamala Harris is the first Asian American and Black woman to be nominated. Her father was from Jamaica, who, like her mother, immigrated to the United States to study and went on to become a distinguished academic.

The progressive Bay Area magazine India Currents ran a piece titled Is Kamala Devi Harris desi enough? In it, the writer Anjana Nagarajan-Butaney sets it out squarely, if gently: “If we desis are honest with ourselves, we know that we are not the most open to cultures of 'otherness'.” And here lies the crux of the matter.

“As a child of immigrants, she truly represents the American melting pot,” a friend said to me when Harris first announced her intention to run for president. There are Democrats and progressives in the community who are happy to see a woman of colour, an “almost-Indian” rise to such a prominent political role.

Yet anecdotal evidence indicates that at least some Indian Americans are not impressed. “Right after she was nominated, I saw a spate of posts (on Indian American social media groups) targeting Kamala,” says Vidya Pradhan, a Bay-Area based writer who has been studying social media disinformation among Indian Americans in this Covid /election year. “There was a lot of hate. It was a super-coordinated anti-Harris wave accusing her of being fake-Indian, fake-Black, a flip-flopper, etc.”

A race problem

If America in general has a race problem, then 'desis' (a term that Indian-Americans like to use to describe themselves) have an even bigger one. Indians in America carried all the trappings of India’s caste, class, and patriarchal ideas with them to the new world. As my friend, a third generation South African Indian, used to say sadly: “You can take the Indian out of India, but not the India out of the Indian.”

[Harris’] mother, Shyamala Gopalan-Harris, raised her daughters as Black women, recognizing that American society would see them as that.

It is widely known that Indian parents prefer their children to only date other Indians, ideally those from the same linguistic region and caste group. If this is the situation in the 21st century, imagine what it must have been like in the 1960s when Harris’s parents met and married! Harris has been widely quoted as saying that her mother Shyamala Gopalan-Harris raised her daughters as Black women, recognizing that American society would see them as that. As Nagarajan-Butaney points out, it must have been pretty clear to Gopalan-Harris that the Black community would probably be more accepting of her mixed-race daughters, than her own.

“Racism in the diaspora continues to be an issue and the solidarity (of South Asians) with other people of colour that can be seen in the UK or Canada has never been strong in the United States. College campuses may give young people the opportunity for (inter-racial) dating and that may lead to some intermixing in future generations, but for now, it is not significant,” says Aparna Rayaprol, a professor of sociology at the University of Hyderabad and an expert on the Indian diaspora.

Pioneering South Asian immigrant groups were relatively smaller in size; nevertheless there was a steady stream of them, who assimilated by marrying [locally].

Indians in America have a long history of struggle and assimilation in the United States. The first significant instance of migration to North America was of Sikh farmers migrating to California in the early 1900s, which at the time was in need of agricultural labour. Due to court rulings in the 1920s that prevented them from acquiring citizenship, and restricted movement so that they were unable to travel back to India to find brides, many of these Sikh farmers married local Mexican women, forming a truly unique community crossing ethnic, racial, language, and religious boundaries. The descendants of these early migrants continue to farm in California’s Central Valley.

Another, largely overlooked migration was that of sailors – many of them Muslim - working on ships arriving in ports on America’s East coast, who chose to jump ship and settle in Eastern and Northern cities such Baltimore, New York, and Detroit. Others were soldiers who were already far away from home, and chose to settle in the United States instead of travelling back halfway across the world. These pioneering South Asian immigrant groups were relatively smaller in size; nevertheless there was a steady stream of them, who assimilated by marrying into African-American and Puerto-Rican communities. The Bengali-Harlem community was one such mixed-race and multi-religious community.

Due to laws specifically restricting non-White immigration, migration from South Asia slowed, and it wasn’t until 1965 – when the Hart-Celler Immigration & Nationality Act was passed encouraging highly-educated immigrants of all races to apply – that Indians began to migrate in larger numbers to the United States. When my parents moved to a small college town in the US in 1968, Indians were still a novelty and cautiously welcomed. My mother recalls a welcome visit from the local pastor’s wife and genuinely curious questions from locals.

Instances of early mixed-race marriages were due to the migration patterns of primarily single men going in search of work. Post-1965 [... immigrants] brought their families with them.

In 1995, when I went to the US as a graduate student (my parents having returned to India eventually), Indians were everywhere and benevolently held up as the model minority. The racial implications of this benevolence were clear: “See, this is how people of colour should behave” — quiet, hard-working and high-achieving, and most importantly, politically passive — a model minority. However, many Indians choose to ignore that implication and continue their earnest quest to achieving the American dream. By 2018, when my daughter left for college in the US, the tide had turned and Indians had become just another community of “people of colour” – celebrated by liberals and vilified by conservatives.

In my conversation with Rayaprol, she explained the difference between earlier migrations and the post-1965 wave and throws light on the insularity.

“Mixed marriages will be rare, as long as the arranged marriage system continues in the diaspora. Instances of early mixed-race marriages were due to the migration patterns of primarily single men going in search of work. Post-1965, mostly educated, upper caste Hindus, and Muslims migrated, and they brought their families with them. The goal was to be an upwardly mobile class, while actively discouraging community inter-mixing.”

The desi vote

How does the insularity of the Indian community play in this big moment where many young progressives are celebrating the nomination of Kamala Harris?

The Indian-American community in general - even in a contested and controversial election year as 2020 - tends to veer right on many issues.

Like many other young liberal Americans, Sathvik Nair, a second-generation Indian American from California’s Bay Area, considers himself considerably left of the Biden-Harris ticket. “When she ran for President, I did not support her”, he told me over the phone. “I supported Sanders and Warren and ultimately voted for Bernie Sanders in the primaries.” What about representation, I asked. “Well, representation is good, but the issues matter more,” he said. And now?

“Since then, I’ve watched her performance in the Senate, her questioning of Brett Kavanaugh, and her backing of the Green New Deal. This is far more indicative of what she has the potential to do, than her previous job as prosecutor.”

Unlike Nair and many of his peers though, the Indian-American community in general - even in such a contested and controversial election year - tends to veer right on many issues. Diaspora research shows that the Indian American community – especially those waves of immigrants who arrived on American shores post-1965 - is culturally and fiscally conservative.

“Support for or against Harris falls along party lines, but there is a vocal and passionate pro-Trump, Anti-Biden/Harris contingent.”

"I see Indian Americans as falling into three groups" says Pradhan. "First, the progressive, liberal, Democrats; second, the pro-Trump, pro-Hindutva group, and a chunk in the middle who don’t care. Support for or against Harris falls along party lines, but there is a vocal and passionate pro-Trump, Anti-Biden/Harris contingent."

Where earlier research had shown that a majority of Indian Americans are Democratic leaning, newer politics of Hindu nationalism among Indians in both India and abroad, as well as a sense of having achieved success in the United States, has many Indian Americans shifting their loyalties to the Republican party.

“There’s probably a shift towards Donald Trump for the money, but also for his anti-immigration and anti-China stances, and his implied anti-Muslim rhetoric and actions,” Pradhan explains.

Birtherism 2.0

The general American response to Harris has also been mixed as people on both sides of the political divide struggle to describe her accurately. Different media reports have called her Black, Asian American, Indian, or mixed-race. Both the New York Times and Washington Post, in their reports on the presumptive nomination last month, settled on the simplest “woman of colour” label.

“The American media are confused because they are not sure whether they want to celebrate the American-born child of immigrants or pigeonhole her as Black or Indian or both. Her own identity as a Black woman of Indian origin is complicated and completely intersectional: inter-religious, upper middle class, educated-professional woman, and inter-racial without being explicitly African American or South Asian” explains Rayaprol.

Harris’s nomination was just another occasion for the trolls and the doubters to come out and play. And as if on cue, an iteration of Birtherism emerged.

The Washington Post reported that in response to a question about her identity, the candidate said, “I describe myself as a proud American.”

But in a social media terrain that pits trolls against genuine users, and where hate speech and online abuse abound, Harris’s nomination was just another occasion for the trolls and the doubters to come out and play. And as if on cue, an iteration of Birtherism emerged. The conspiracy theory floated by conservatives to claim that Barack Obama was not an American citizen was repurposed to cast doubt on Harris’ eligibility to run for office. Donald Trump was one of the foremost proponents of the original version of this theory and his constant and vehement espousing of it can be credibly linked to the rise of his popularity among right wing and Republican voters.

In this latest iteration, the claims are varied and equally fictitious: that Harris was not born in the US and she may have been born in Canada (where she lived for a while); or that even if she was born in the US, she was not eligible to run as her parents had not been legal residents for enough time before her birth. The caveats point to the trolls’ real problem– her racial identity.

Conclusion

As a one-time member of the Indian diaspora and a regular voter, I have followed the career of Harris for the last several years. While she seems to be comfortable with her Indian name and heritage, she has definitively crafted a public image of a hardworking, civic-minded Black woman and public servant.

The questions of Harris’ authenticity only underscore America’s unresolved problem with race.

As the daughter of two highly educated academics, she could have chosen to study at an Ivy League or prestigious private school. Yet she chose to go to Howard University – an HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) - equally prestigious, but very niche to the African American community. Her rise from public prosecutor to California’s Attorney General, and from there to the US Senate in 2016, making her the first South Asian American and only the second African American woman ever elected to that office, position her as extremely well qualified to serve as Vice President of the United States.

Like Obama, Harris too will have to contend with not just questions of legal eligibility, but also questions of authenticity. Is she a real African American? Conservative writers have pointed out that as the child of Indian and Jamaican immigrants, her ancestry was not tied to African slaves in America. Thus, they argued, she could never truly represent the African-American community. (Obama, the son of a white American woman and a visiting Kenyan student, was also subject to similar criticism.)

The questions of Harris’ authenticity only underscore America’s unresolved problem with race. Despite the much touted espousing of the ‘melting pot’ and ‘tossed salad’ concepts of American society, liberals and conservatives alike continue to struggle with racial identities, mixed-race identities, and people of colour in general.