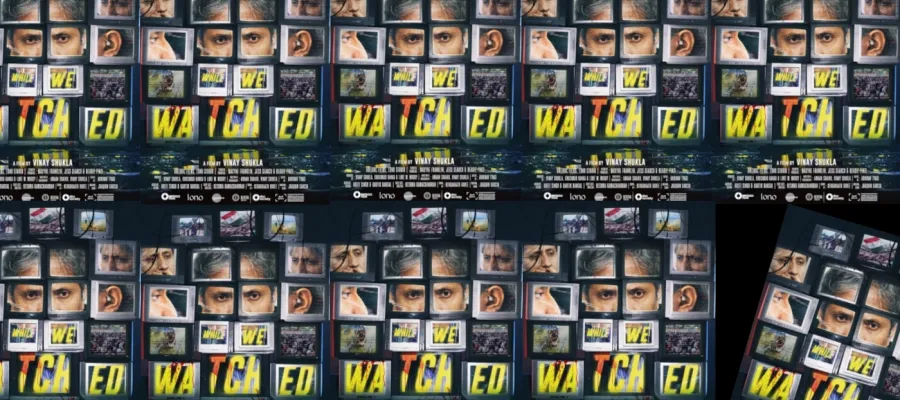

The line for the premiere of Vinay Shukla’s While We Watched at Manhattan’s Independent Film Channel (IFC) Center had only just begun to form when we arrived last weekend. As it got closer to the 7 pm start, Ravish Kumar – the film’s protagonist – appeared, and started making his way down the line of waiting ticket holders, shaking hands and thanking people for being there. We watched him approach. The American woman in line ahead of us shook his hand politely but somewhat bemusedly. She clearly had no idea who he was. “I’m the person in the film you’re about to see,” he explained kindly, gesturing over his shoulder to the poster. Thankfully, I more than made up for their disinterest. “It’s an absolute honour to meet you” was all I managed to say before I inexplicably started to cry. No doubt Ravish is used to this level of fandom. “Chalo, photo le lete hai” (“Come, let’s take a photo”), he said, allowing me some relief before he moved off down the line.

That wasn’t the end of my tears. For anyone invested in India and its future, While We Watched is a harrowing movie. Shot between 2018 and 2020 and prior to the recent acquisition by the Adani group of New Delhi Television Limited (NDTV), one of India’s most beloved and well-respected news media companies, I worried that it would seem dated. This is partly because everything pre-pandemic feels like it belongs to a different era but is also an indictment of how used we are to the very thing the film critiques – the shrill frenetic 24/7 news cycle, where anything that isn’t “Breaking!” isn’t even news. Far from feeling stale, the film was a visceral reminder of events that we cannot, and should not, forget.

In contrast to much of mainstream media, Ravish, and NDTV more generally, were known for sober, well-researched, people-focused shows, highlighting issues of national local interest.

The film is centred on Ravish Kumar, who worked at NDTV for close to 30 years from 1994 to 2022, but is in equal measure a story of the decline not just of NDTV, but of the overall level of discourse in Indian TV news channels.

Aided by an inspired background score, fast-paced frenetic scenes mirror the cacophony created by news anchors on major news channels – uninformed 'debates' that devolve into shouting matches, insults traded freely, the callous, calculated, irresponsible whipping up of majority sentiment and the stoking of fear, and the reluctance to hold the central government to account. A friend watching the movie with me said he was in a constant state of anxiety.

In contrast to much of mainstream media, Ravish, and NDTV more generally, were known for sober, well-researched, people-focused shows, highlighting issues of national local interest – unemployment, national security, soaring inflation – but also more local governance issues, such as the evergreen concerns of bijli, sadak, pani (electricity, roads, water) or student distress. We see the draw of this throughout the film, with petitioners constantly seeking out Ravish, begging him to amplify their stories.

Of course, it isn’t just the delivery and style that sets apart Ravish – and others at NDTV – during that time. It was the fact that they consistently spoke truth to power, by choosing not to limit themselves to sensationalism and ideologically driven news stories. This has a real financial cost. The opening scene shows Ravish walking through the rubble of a demolished floor of a building, lighting the way through the darkness with his mobile phone. We learn later that NDTV was forced to give up this floor of their building due to financial distress. Advertisement revenues, and hence many editorial (and ethical) decisions, are determined by television rating points (TRPs), a measure of the popularity of a programme or channel. Real news just doesn’t cut it anymore. In the film, after Ravish gives a speech at a college function, a student starts her question by saying she is a big fan of his show. “You should tell my producers,” quips Ravish, to resounding laughter. “According to them I am the zero TRP rating guy.”

The drip-drip of people being laid off or leaving NDTV for better paying jobs is an essential part of the film’s backdrop. We see the first farewell party, with the ubiquitous black forest cake being cut and people congratulating the person leaving. Another person leaves, another cake is cut. Then another. Now no one bothers with ceremony. The cake is dumped onto an A4 piece of paper and left half-eaten. In one of the film’s most poignant scenes, Swarolipi, a key member of the production crew for Ravish’s show comes into his cabin to confess she too is moving on. “Maine toh kabhi socha hi nahi tha ki tum bhi mujhe chodke chali jaogi” (“I would never have dreamt that even you would someday leave me”), he says.

The drip-drip of people being laid off or leaving NDTV for better-paying jobs is an essential part of the film’s backdrop.

The viewer is left with the sense of one man left standing while everything around him – people, institutions – slowly crumbles. This is enhanced by the way the movie is shot, with little outdoor footage and many close-up shots given the distinct impression of the walls closing in. As the pressure grows, tempers begin to fray in the newsroom. Someone bungles the teleprompter text and in a rare display of frustration you see an otherwise dignified Ravish lash out. “Stop shouting at me!” the member of the production crew yells in response. And yet through all this, the incredible decency of the man is inescapable. Ravish signs off the last show that Swarolipi works on by paying her tribute, and then sits in his chair for a moment after the television camera stops rolling, a small wry smile playing on his lips.

There is, of course, another cost to holding the government accountable, a real and ever-present threat of actual physical harm. We see this play out in the incessant ringing of Ravish’s phone, the constant threats to his life, his security detail. “Tum gadhe ho” (“You’re a fool”), his daughter admonishes him at one point, as she pats his cheek affectionately. Maybe. But when he convinces a troll to stop abusing him and instead join in singing Saare Jahaan Se Accha over the phone, you have to wonder if he is also a magician and what toll performing that magic exacts.

Both this movie and Shukla’s previous – An Insignificant Man, that chronicled the heady early days of Arvind Kejriwal and the Aam Aadmi Party – are centred on a single character who stands somewhat apart from those around him, but whose story is so much bigger than themselves.

Aptly, the movie ends with Ravish packing up and heading out of the NDTV office, passing the reception desk just as the phone rings with another petitioner’s request.

In the Q&A afterwards, Vinay Shukla said he wanted to counter the Hollywood narrative of a single story that changes the world with a film that shows that a hundred stories can still change nothing. He certainly did that. Unlike An Insignificant Man, the viewer of While We Watched leaves not with a sense of hope, or optimism, but with a lingering helplessness, a despondency, a feeling that we have gone too far to wind this back. But we are also left with immense respect for what Ravish stood for, continues to stand for, and how for many of the voiceless, he certainly changed a lot. Aptly, the movie ends with Ravish packing up and heading out of the NDTV office, passing the reception desk just as the phone rings with another petitioner’s request.

While We Watched has been released in New York and London and elsewhere but may never reach Indian audiences. It still does not have an Indian distributor. The film asks difficult questions: Who manages the narrative, who really determines what the audience can see? For that very reason, it is a courageous film – one that tells the story of our times.

Kalyani Raghunathan is an independent researcher.